Shellshock

By 1914 British doctors working in military hospitals noticed patients suffering from "shell shock". Early symptoms included tiredness, irritability, giddiness, lack of concentration and headaches. Eventually the men suffered mental breakdowns making it impossible for them to remain in the front-line. Some came to the conclusion that the soldiers condition was caused by the enemy's heavy artillery. These doctors argued that a bursting shell creates a vacuum, and when the air rushes into this vacuum it disturbs the cerebro-spinal fluid and this can upset the working of the brain.

Some doctors argued that the only cure for shell-shock was a complete rest away from the fighting. If you were an officer you were likely to be sent back home to recuperate. However, the army was less sympathetic to ordinary soldiers with shell-shock. Some senior officers took the view that these men were cowards who were trying to get out of fighting.enemy shell-fire.

Philip Gibbs, a journalist on the Western Front, later recalled: "The shell-shock cases were the worst to see and the worst to cure. At first shell-shock was regarded as damn nonsense and sheer cowardice by Generals who had not themselves witnessed its effects. They had not seen, as I did, strongly, sturdy, men shaking with ague, mouthing like madman, figures of dreadful terror, speechless and uncontrollable. It was a physical as well as a moral shock which had reduced them to this quivering state."

Between 1914 and 1918 the British Army identified 80,000 men (2% of those who saw active service) as suffering from shell-shock. A much larger number of soldiers with these symptoms were classified as 'malingerers' and sent back to the front-line. In some cases men committed suicide. Others broke down under the pressure and refused to obey the orders of their officers. Some responded to the pressures of shell-shock by deserting. Sometimes soldiers who disobeyed orders got shot on the spot. In some cases, soldiers were court-martialled.

Official figures said that 304 British soldiers were court-martialled and executed. A common punishment for disobeying orders was Field Punishment Number One. This involved the offender being attached to a fixed object for up to two hours a day and for a period up to three months. These men were often put in a place within range of enemy shell-fire.

Primary Sources

(1) Innes Meo, diary entries (September, 1916)

25th September: My 30th birthday, an awful day. Still in the trenches. In the afternoon I was called to see the doctor. It is possible if I live I may be invalided home. This night I was sent on an ammunition job. Conducting a party of 50 bombers to stores. It was hell! I was already tired and ill.

28th September: A terrible bombardment was started, it is simply awful to hear, as I write the guns are crashing, roaring and the din is like a collision of hundreds of bad thunderstorms. God knows what mothers are losing their sons now.

30th September: Sent to Casualty Clearing Station at Guezancourt. Officer in next bed with awful shell-shock, also airman with broken nerves. God, what sights.

8th October: I hear I am off to England at 4.30 p.m. Thank God I am about to leave this miserable country. I hope to God I never return. Have been tortured all the morning by dreadful thoughts. How I wish I had a girl to care for me, waiting in England for me.

(2) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

Having now been in the trenches for five months, I had passed my prime. For the first three weeks, an officer was of little use in the front line; he did not know his way about, had not learned the rules of health and safety, or grown accustomed to recognizing degrees of danger. Between three weeks and four weeks he was at his best, unless he happened to have any particular bad shock or sequence of shocks. Then his usefulness gradually declined as neurasthenia developed. At six months he was still more or less all right; but by nine or ten months, unless he had been given a few weeks' rest on a technical course, or in hospital, he usually became a drag on the other company officers. After a year or fifteen months he was often worse than useless. Dr W. H. R. Rivers told me later that the action of one of the ductless glands - I think the thyroid - caused this slow general decline in military usefulness, by failing at a certain point to pump its sedative chemical into the blood. Without its continued assistance A man went about his tasks in an apathetic and doped condition, cheated into further endurance. It has taken some ten years for my blood to recover.

Officers had a less laborious but a more nervous time than the men. There were proportionately twice as many neurasthenic cases among officers as among men, though a man's average expectancy of trench service before getting killed or wounded was twice as long as an officer's. Officers between me ages of twenty-three and thirty-three could count on a longer useful life than those older or younger. I was too young. Men over forty, though not suffering from want of sleep so much as those under twenty, had less resistance to sudden alarms and shocks. The unfortunates were officers who had endured two years or more of continuous trench service. In many cases they became dipsomaniacs. I knew three or four who had worked up to the point of two bottles of whisky a day before being lucky enough to get wounded or sent home in some other way. A two-bottle company commander of one of our line battalions is still alive who, in three shows running, got his company needlessly destroyed because he was no longer capable of taking clear decisions.

(3) Corporal Henry Gregory served with the 119 Machine Gun Company.

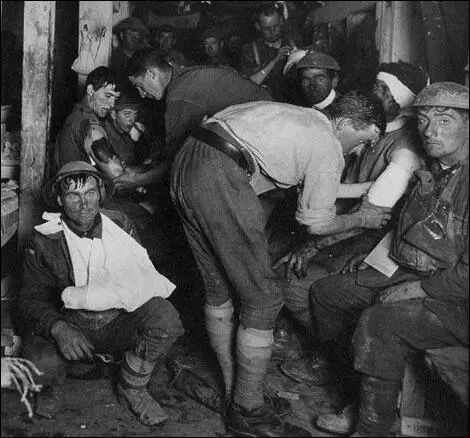

It was while I was in this Field Hospital that I saw the first case of shell-shock. The enemy opened fire about dinner time, as usual, with his big guns. As soon as the first shell came over, the shell-shock case nearly went mad. He screamed and raved, and it took eight men to hold him down on the stretcher. With every shell he would go into a fit of screaming and fight to get away.

It is heartbreaking to watch a shell-shock case. The terror is indescribable. The flesh on their faces shakes in fear, and their teeth continually chatter. Shell-shock was brought about in many ways; loss of sleep, continually being under heavy shell fire, the torment of the lice, irregular meals, nerves always on end, and the thought always in the man's mind that the next minute was going to be his last.

(4) Philip Gibbs was a journalist who reported the war on the Western Front.

The shell-shock cases were the worst to see and the worst to cure. At first shell-shock was regarded as damn nonsense and sheer cowardice by Generals who had not themselves witnessed its effects. They had not seen, as I did, strongly, sturdy, men shaking with ague, mouthing like madman, figures of dreadful terror, speechless and uncontrollable. It was a physical as well as a moral shock which had reduced them to this quivering state.

(5) Frank P. Crozier wrote about his experiences in the First World War in his book A Brass Hat in No Man's Land in 1930.

A strong rabble of tired, hungry and thirsty men approached me. "Where are you going I ask?" They are given a drink and hunted back to fight. Another more formidable party cut across. They are damned if they are going to stay. A young officer heads them off. They push by him, he draws his revolver. They take no notice. He fires. Down drops a British soldier at his feet. The effect is instantaneous. They turn back.

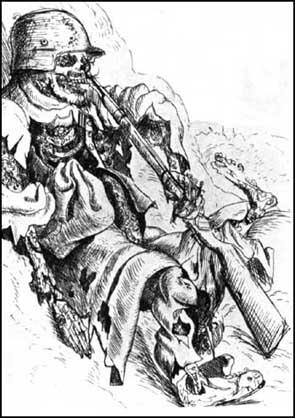

(6) George Grosz, Autobiography of George Grosz (1955)

One day, I gathered that I was to be shot for desertion. Luckily Count Kessler heard about it as well, and interceded on my behalf. In the end, they pardoned me and packed me off to a home for the shell-shocked. Shortly before the end of the war, I was discharged a second time, once again with the observation that I was subject to recall at any time.

(7) Philip Gibbs reported the war for The Daily Chronicle. He wrote about his experiences in his autobiography, Adventures in Journalism.

I saw a sergeant-major convulsed like someone suffering from epilepsy. He was moaning horribly with blind terror in his eyes. He had to be strapped to a stretcher before he could be carried away. Soon afterwards I saw another soldier shaking in every limb, his mouth slobbered, and two comrades could not hold him still. These badly shell-shocked boys clawed their mouths ceaselessly. Others sat in the field hospitals in a state of coma, dazed, as though deaf and dumb.

(8) John Raws died at the Battle of the Somme. He wrote a letter to his brother just before he was killed (12th August 1916)

The Australian casualties have been very heavy - fully 50% in our brigade, for the ten or eleven days. I lost, in three days, my brother and my two best friends, and in all six out of seven of all my officer friends (perhaps a score in number) who went into the scrap - all killed. Not one was buried, and some died in great agony. It was impossible to help the wounded at all in some sectors. We could fetch them in, but could not get them away. And often we had to put them out on the parapet to permit movement in the shallow, narrow, crooked trenches. The dead were everywhere. There had been no burying in the sector I was in for a week before we went there.

The strain - you say you hope it has not been too great for me - was really bad. Only the men you would have trusted and believed in before, proved equal to it. One or two of my friends stood splendidly like granite rocks round which the seas stormed in vain. They were all junior officers. But many other fine men broke to pieces. Everyone called it shell shock. But shell shock is very rare. What 90% get is justifiable funk, due to the collapse of the helm - of self-control. I felt fearful that my nerve was going at the very last morning. I had been going - with far more responsibility than was right for one so inexperienced - for two days and two nights, for hours without another officer even to consult and with my men utterly broken, shelled to pieces.

(9) Charles Hudson, journal entry, quoted in Soldier, Poet, Rebel (2007)

He was a lusty raw-boned lad, unlikely one would think to suffer from nerves, or a mental breakdown. He had been quiet of late, but I had not realised that his nerves were unusually affected. We were very short of officers, and in any case to send an officer from another platoon was unfair and might do irreparable damage to his own prestige in the company. I reasoned with him and persuaded him to go. He was killed. The men said he had refused to lie down when machine gun fire swept across no man's land, as the rest of the party had quite rightly done. Fire at night was un-aimed and of no particular danger or significance. The men thought him foolhardy. I wondered if he had been paralysed by his own fear, or so afraid of being afraid that he had refused to allow himself to take cover.

(10) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

Some men in an army are what one terms cowards, that is they can't control their fear and their nerves break sooner or later. They try to run or hide in the first shell-hole, or shoot themselves in hand or foot and in extreme cases, deliberately seek the death they fear by putting their heads over the top of a trench; I've known that to happen. Then there is a larger group, whose nerves are dull. They don't much fear danger, or grow used to it, and carry on calmly with more interest most of the time in how they are fed and clothed and paid, and whether the trenches are damp or dry, and what the girls and eats and drinks will be like in their next period of rest behind the line, than in the enemy's shelling or their own fears. Finally there are the exceptional men, one in ten thousand or more, like Alexander and Sweeney, who get a real kick from danger, and the greater the danger the greater the kick.