Quentin Reynolds

Quentin Reynolds was born in New York City on 11th April, 1902. He became a sports journalist working for the New York Telegram. Reynolds became friendly with Heywood Broun, the newspaper's leading columnist. According to a mutual friend: "Reynolds patterned himself in the Broun mold, not only in his casual attitude toward the gents' tailoring industry but in his manner and political stance; he also adopted the seemingly artless and simplistic Broun literary style, which wasn't as easy to imitate as many would-be imitators hoped."

Reynolds was a regular visitor to Broun's home, Sabine Farm, near Stamford in Fairfield County. Reynolds said of Broun, who at that time was earning over $1,000 a week: "Tough-minded about social justice and conditions for the working man, for example, he was indifferent to his own wages and hours and was even a markedly easy touch. A slashing writer in his columns, he appeared to many of his readers an agnostic; yet during the years I knew him he was groping toward his belief in God."

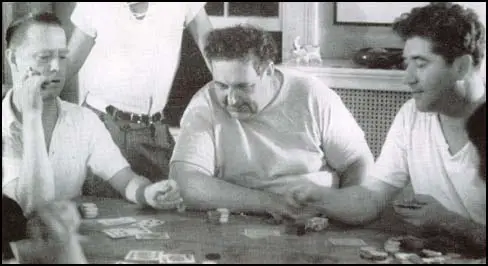

In 1933 Reynolds became associate editor of Collier's Weekly. According to Richard O'Connor, the author of Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975): "Another addition to the Broun circle at the Sabine Farm was a burly red-haired Irishman named Quentin Reynolds, a sportswriter on the World-Telegram whose dispatches from the Brooklyn Dodgers' training camp had attracted Broun's favorable attention... Between Broun's newfound friends and additions to the Sabine Farm drinking, debating, and poker-playing society, Pegler and Reynolds, there were few intimations of the palship which bound them to Broun. Both were of Irish ancestry, but Reynolds was the bluff outgoing type while Pegler was the angry repressed man staring into the turf fire in a country pub."

During the Second World War he accompanied the soldiers led by General George S. Patton. On 10th August 1943, Patton visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital to see if there were any soldiers claiming to be suffering from combat fatigue. He found Private Paul G. Bennett, an artilleryman with the 13th Field Artillery Brigade. When asked what the problem was, Bennett replied, "It's my nerves, I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton exploded: "Your nerves. Hell, you are just a goddamned coward, you yellow son of a bitch. Shut up that goddamned crying. I won't have these brave men here who have been shot seeing a yellow bastard sitting here crying. You're a disgrace to the Army and you're going back to the front to fight, although that's too good for you. You ought to be lined up against a wall and shot. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself right now, God damn you!" With this Patton pulled his pistol from its holster and waved it in front of Bennett's face. After putting his pistol way he hit the man twice in the head with his fist. The hospital commander, Colonel Donald E. Currier, then intervened and got in between the two men.

Colonel Richard T. Arnest, the man's doctor, sent a report of the incident to General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The story was also passed to the four newsmen attached to the Seventh Army. Although Patton had committed a court-martial offence by striking an enlisted man, the reporters agreed not to publish the story. Reynolds agreed to keep quiet but argued that there were "at least 50,000 American soldiers on Sicily who would shoot Patton if they had the chance."

Reynolds was described as the bravest war correspondent since Floyd Gibbons. The journalist, Oliver Pilat, pointed out: "Reynolds was the kind of foreign correspondent who called First Lords of the Admiralty by their first names... At the time of the Nazi aerial blitz of London during the war, he had abused Hitler and praised British courage so successfully in broadcasts from London that an English poll placed him second in popularity only to his good friend, Winston Churchill. At the request of another close friend, the late President Roosevelt, Reynolds had returned from abroad in 1944 to deliver one of the roundup orations at the fourth-term Democratic national convention in Chicago."

Reynolds was also the author of several books about the war including, The Wounded Don't Cry (1941) A London Diary (1941), Convoy (1942), Only the Stars are Neutral (1942), Dress Rehearsal: The Story of Dieppe (1943), The Curtain Rises (1944), Officially Dead: The Story of Commander C D Smith, USN; The Prisoner the Japs Couldn’t Hold (1945), The Battle of Britain (1953) and The Amazing Mr Doolittle; A Biography of Lieutenant General James H Doolittle (1953).

However, before he could start work he was taken ill. Broun's friends were appalled by the decision of Westbrook Pegler to write critically about Broun while he was unable to defend himself. Without any basis of truth, Pegler accused Broun of supporting Soviet press censorship and compared him to Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler and Earl Browder, the leader of the American Communist Party: "I have seen recent superficial expressions of disappointment in Moscow, but never an outright incantation, and even if I saw one I would have to treat it the same as I treat changes of front by Stalin, Hitler and Earl Browder."

In 1949 Dale Kramer published his book, Heywood Broun. It was reviewed by Quentin Reynolds in the New York Tribune. At the end of the review he commented on Westbrook Pegler's article on Heywood Broun just before his death: ""Broun could talk of nothing but Pegler's attack on him.... It seemed incredible that he was allowing Pegler's absurd charge of dishonesty to hurt him so. But not even Connie could make him dismiss it from his mind. The doctor told him to relax; he'd be all right if he got some sleep. But he couldn't relax. He couldn't sleep."

Westbrook Pegler was furious and in his syndicated column the next day he launched a savage attack on Reynolds. Pegler began his article by describing the New York Tribune as a "pro-Communist newspaper - always has been and still is." Reynolds was also a "pro-Communist". According to Richard O'Connor, Pegler said "Reynolds was a war profiteer, a social climber, and a man who bent to die his shoelace when the check was presented in a nightclub or restaurant; that he was a member of the parasitic, licentious group that surrounded Broun. He further charged that Reynolds was a nudist, that he was present at a frolic at the Sabine Farm during which a conspicuous Negro Communist seduced a susceptible young white girl. The charge that most deeply wounded Reynolds, however, was Pegler's claim that Reynolds, then unmarried, had proposed to Connie Broun on the trip to the cemetery from St. Patrick's Cathedral."

The article had run in 186 newspapers with a combined circulation of 12,000,000. Reynolds said to his wife, Virginia Peine, the actress: "Would you mind if I sued?" She replied: "I'd have divorced you if you didn't." Reynolds engaged the celebrated trial lawyer Louis Nizer and filed a $50,000 libel suit. However, Reynolds did not receive any support from the media industry. C had purchased 310 articles from Reynolds between 1933 and 1949. After the so-called libel column appeared the magazine bought no new material from him. Requests to appear on radio also came to an end. His agent, Mark Hanna, found that he was now "too controversial".

Westbrook Pegler went back on the attack and described Reynolds as a "Communist traitor". Mrs. Reynolds went to see Pegler at his office on East 45th Street in New York City. She asked him: "Why don't you let up? Do you want to destroy us?" He replied that if the libel suit were dropped he promised he would never write another word about her husband. When he heard what Pegler had said, Reynolds told his wife that he had "no intention of being bludgeoned into submission".

The trial did not take place until 1954. Pegler had to endure a long cross-examination by Louis Nizer. When the lawyer drew near to hand him a document, he shrilled unexpectedly: "Get away from me, get away!" Thereafter a court attendant was designated to hand exhibits back and forth between the men. At the end of his testimony Nizer pointed out that Pegler had contradicted himself under oath in 130 instances. Pegler replied that this was due to Nizer's "exhausting brain-washing tactics".

Westbrook Pegler claimed that Heywood Broun had immoral parties at Sabine Farm. Once again he insisted that an unnamed "Negro singer seduced... a susceptible white girl". He added that the farm was "a low dirty place" and Broun was "filthy, uncombed and unpressed, with his fly open, looking like a Skid Row bum." Reynolds "imitated but did not exactly emulate" Broun's sartorial carelessness.

Famous war correspondents including John Gunther, Edward R. Murrow, Walter Kerr, Ken Downs and Lionel Shapiro took the stand to say that Reynolds had acted bravely under fire. It was pointed out that he was one of the last foreign correspondents to leave Paris before the German Army moved in. Another witness claimed that Reynolds nearly died from sun exposure after crawling through enemy lines during the Desert War. Others gave evidence of his courage while reporting the Blitz. As Oliver Pilat, the author of Pegler: Angry Man of the Press (1963) explained: "His (Reynolds) reputation was genuine enough. In the face of it, Pegler's charges of slackerism, war profiteering and cowardice fell flat."

During his testimony Westbrook Pegler described Reynolds as being "so far to the left as to be almost out of the Democratic Party... I don't say he is not loyal and a good American. I say he is a dope!" Louis Nizer raised doubts about Reynolds so-called "pro-Communist" views by producing a letter from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover certifying Reynolds as the sort of "confirmed liberal" who constituted the country's best bulwark against communism.

In the witness box Pegler claimed that Reynolds had once gone "nuding along the public road with his girl friend of the moment". He admitted that he had never seen Reynolds without clothes but learned of Reynolds' nude bathing at Sabine Farm from Connie Broun. Pegler claimed that while she was rowing on the lake, Reynolds was in shallow water, while wearing no trunks. There he was "with his lavalliere dangling while she looked at the sky and the trees." When she gave evidence she denied she ever told Pegler this story. In fact, she never went rowing as she dreaded the water because she was unable to swim. Connie also denied that Reynolds proposed to her during the funeral. She pointed out that she was accompanied by Broun's son, Heywood Hale Broun and Bishop Fulton J. Sheen during the trip to the cemetery.

In his final summary, Louis Nizer pointed out that he was able to call twenty-eight character witnesses for Reynolds, whereas there had been not a single character witness for Pegler. Why? "There isn't another writer that has a worse reputation for inaccuracy, indecency, for recklessness, for malice, for hatred, for viciousness, for besmirching people's characters and destroying them."

The jury, eight men and four women, deliberated for thirteen hours. It returned a verdict of $175,001. It was later revealed that the original vote was for $475,000. However, to get an unanimous verdict, required by law, it was agreed to reduce it to $175,001. Despite a series of appeals, the verdict was not reduced. With the addition of interest and other charges, Reynolds won almost $200,000, the largest amount ever collected in an American libel case.

Quentin Reynolds died in San Francisco on 17th March, 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard O'Connor, Heywood Broun: A Biography (1975)

Another addition to the Broun circle at the Sabine Farm was a burly red-haired Irishman named Quentin Reynolds, a sportswriter on the World-Telegram whose dispatches from the Brooklyn Dodgers' training camp had attracted Broun's favorable attention. In the several years before Reynolds switched to magazine writing as a member of the Collier's staff and became one of the outstanding correspondents of World War II, Broun practically adopted him and made him a favorite drinking companion. Reynolds, according to one Broun intimate, patterned himself in the Broun mold, not only in his casual attitude toward the gents' tailoring industry but in his manner and political stance; he also adopted the seemingly artless and simplistic Broun literary style, which wasn't as easy to imitate as many would-be imitators hoped....

Between Broun's newfound friends and additions to the Sabine Farm drinking, debating, and poker-playing society, Pegler and Reynolds, there were few intimations of the palship which bound them to Broun. Both were of Irish ancestry, but Reynolds was the bluff outgoing type while Pegler was the angry repressed man staring into the turf fire in a country pub. Eventually mutual distaste would develop into an enmity and a ruinously debilitating libel suit, which sprayed vitriol over the Fairfield literary colony and constituted the epitaph, many years later, for the long summer afternoons on which Broun and his friends disported themselves in rural Connecticut.

(2) Oliver Pilat, Pegler: Angry Man of the Press (1963)

Reynolds was the kind of foreign correspondent who called First Lords of the Admiralty by their first names.... At the time of the Nazi aerial blitz of London during the war, lie had abused Hitler and praised British courage so successfully in broadcasts from London that an English poll placed him second in popularity only to his good friend, Winston Churchill. At the request of another close friend, the late President Roosevelt, Reynolds had returned from abroad in 1944 to deliver one of the roundup orations at the fourth-term Democratic national convention in Chicago.