Floyd Gibbons

Floyd Gibbons was born in Washington in 1887. His father ran a butter and egg company. He wanted Gibbons to join the family business but he insisted on attending Georgetown University. On leaving in 1907 he found work as a police reporter for the Minneapolis Daily News.

In 1909 Gibbons moved to the Minneapolis Tribune. According to David Randall, the author of The Great Reporters (2005): "As the main man covering crime, he had the pick of the city's murders, fires, brawls and head-breakings. He spent his days and nights hanging around police stations and courts, periodically scuttling off to the scene of the most colourful crimes. These, invariably, were committed in the city's slums, a teeming wellhead of stories that rapidly gave Gibbons the kind of education in the rawer side of human nature that no college can provide."

Gibbons first major breakthrough was his reporting of a story about John F. Dietz, who became involved in a shoot-out with the police at his home near the Cameron Dam on the Thornapple River in October, 1910. Gibbons managed to get into Dietz's home and carried out an exclusive interview with the fugitive. It took more than 1000 rounds fired at the homestead before Dietz eventually surrendered. During the fighting a deputy was killed and he was tried for manslaughter and was duly sentenced to life imprisonment.

His next big story was the fire at the Brunswick Hotel in Minneapolis. The 200 guests were rescued by firefighters. Gibbons knew that the hotel was used by wealthy businessmen and their mistresses. He therefore "dashed through the smoke and falling debris into the lobby, up to the reception counter, and grabbed the register with its precious and incriminating details". The following morning Gibbons published his story of the fire, including the names of all the guests in the register.

In 1912 Gibbons joined the Chicago Tribune. During the Mexican Revolution he managed to interview Pancho Villa. He also was with the rebels when they captured Chihuahua. Villa was so impressed with the bravery of Floyd Gibbons that he ordered a private carriage made for him and coupled to his own train. Gibbons spent the next four months with Villa reporting on his military achievements.

During the First World War Gibbons was sent to the Western Front to cover the conflict. At the time Germany had just issued a threat that any ship entering the Atlantic approaches to the British Isles and France was liable to be sunk without warning. In order to protect him from danger, his newspaper booked him a berth on the SS Frederick VIII, which also carried the returning German ambassador to the United States, Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff. Gibbons rejected this idea and instead opted to take the first boat out of New York to defy the German ultimatum. Gibbons boarded the Laconia on 17th February, 1917. It has been argued that "When he went aboard, the Chicago Tribune saw to it that he was provisioned with a special life preserver, flasks of brandy and fresh water, and several flashlights."

On 25th September, Gibbons' ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat 200 miles off the Irish coast and sank within the hour. Gibbons and most of the passengers and crew took to the lifeboats and were picked up by a British minesweeper, and were taken to Queenstown. It was from here that Gibbons was able to file his exclusive report for the Chicago Tribune that included: "The torpedo had hit us well astern on the starboard side and had missed the engines and the dynamos. I had not noticed the deck lights before. Throughout the voyage our decks had remained dark at night and all cabin portholes were clamped down and all windows covered with opaque paint. Steam began to hiss somewhere from the giant gray funnels that towered above. Suddenly there was a roaring swish as a rocket soared upward from the captain's bridge, leaving a comet's tail of fire. I watched it as it described a graceful arc in the black void overhead, and then, with an audible pop, it burst in a flare of brilliant colors. There was a tilt to the deck. It was listing to starboard at just the angle that would make it necessary to reach for support to enable one to stand upright. In the meantime electric floodlights - large white enameled funnels containing clusters of bulbs - had been suspended from the promenade deck and illuminated the dark water that rose and fell on the slanting side of the ship."

The eyewitness account of the Laconia being sunk by a German U-boat made headline news all over the world. Gibbons's story was acclaimed throughout the United States, and "was read from the floor of both houses of Congress." It has been pointed out by Sally J. Taylor that Gibbons's story provided "evidence that the Germans' unrestricted policy of submarine warfare, even against neutral shipping, was a convincing reason why Americans could no longer stay out of the war." Taylor added: "Floyd Gibbons was credited with writing the story that helped to persuade the Yanks" to declare war on Germany.

On 8th June, 1917, Major General John J. Pershing sailed into Liverpool as the advance guard of the United States Army. British censors would not allow reporters to say where he was landing. Gibbons therefore wrote in the Chicago Tribune: "Major General John J. Pershing landed at a British port today and was greeted by the Lord Mayor of Liverpool."

Later that month Gibbons arrived in France where he joined other journalists included Richard Harding Davis, Philip Gibbs, Percival Phillips, Wythe Williams, William Beach Thomas, Henry Perry Robinson, Herbert Russell, Frederick Palmer, Floyd Gibbons, Damon Runyon, Edwin L. James and William Bolitho. Gibbons wanted to see the action and quickly headed for the Western Front. He was warned by the censors to stay out of unauthorized places, Gibbons routinely ignored them, calling his more cooperative colleagues "lazy louts who won't get out after their own news."

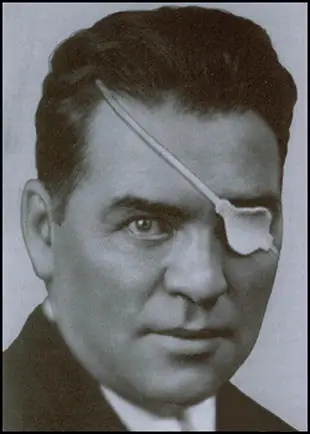

In June 1918 Gibbons went out on patrol with Major Benjamin S. Berry and the Fifth Marines in woods near Lucy-le-Bocage. While crossing a wheat field they came under heavy machine-gun fire. Berry was hit and Gibbons began to crawl towards him. According to his friend, John Gunther: "There was a sudden whish and bits of wheat were clipped off, by a spray of machine gun bullets. (Gibbons) dropped. He got up again at once, feeling his arm, where he was hit slightly. But he dropped again, turned over, and his companion saw his eye, exactly like a whole small raw egg, roll slowly down his right cheek. There it wobbled and swayed, but stayed, held by greyish-red filaments: they looked like nerves. (Gibbons) had to lie in the wheat all day, holding his eye there, low on the cheek."

The bullet "took out his left eye, fractured his skull and exited, ripping a three-inch hole in the right side of his helmet." The French authorities later recalled: "Rescued several hours later and carried to a dressing station, he insisted on not being cared for before the wounded who had arrived before him." When he was told he had lost his eye he replied: "Well Doc, I won't have to squint down the neck of a bottle anymore, like you guys."

David Randall, the author of The Great Reporters (2005) has argued: "Gibbons recovered quickly, and, sporting the white eye patch that was to be part of his own mythology, was back at the front by mid-July. A month later, the French awarded him the Croix de Guerre, and was chosen to make a lecture tour of the US. He arrived back in New York to find he was the war's latest celebrity. A Marine guard of honour and jostling newsmen greeted him." Gibbons was invited to a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson in the White House.

In the summer of 1921, the Chicago Tribune sent Gibbons to report on the new policy of war communism in Russia. Maxim Litvinov was placed in charge of giving permission to the journalists to go into the famine areas. Those who arrived from the United States included George Seldes and Walter Duranty. Seldes later commented in his autobiography, Witness to a Century (1987): "We had been instructed to proceed to the Hotel Savoy, a small hostelry near the Kremlin, and we were assigned rooms on the second or third floor. But Floyd Gibbons had beaten all of us to Moscow. We heard that he was now in Sumara, the worst-hit city in the famine zone."

According to Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990): "Floyd Gibbons arrived in Russia in order to report , now a dashing figure with his black eye patch, had chartered a plane and told Litvinov he planned to fly into Red Square in it, giving his paper a big scoop. Appalled at the prospect, Litvinov instead offered Gibbons the chance to go early into the area stricken by famine, exactly what Gibbons had been after all along. Once into the Ukraine, Gibbons sent his dispatches back by messenger and by train to Moscow, where they were cabled directly to the United States." Walter Duranty of the New York Times said that Gibbons "fully deserved his success because he had accomplished the feat of bluffing the redoubtable Litvinov stone-cold... a noble piece of work." Over the next few days Gibbons was the only reporter to document the horrifying prospect of the deaths of as many as fifteen million people from starvation.

Sally J. Taylor has argued: "Gibbons steadfastly recorded the suffering he witnessed, without glossing over ugly facts or resorting to sentimentality. His stories offered no easy solution to the horrors of the famine." Gibbons pointed out that the Russian peasants had been forced to eat a "black, greasy clay" which could be found locally. Because the clay could not be eliminated by the system, it remained in the children's intestines. "Then comes the swelling of the abused innards, together with masses of worms, and the horrible distension that changes the likeness from that of a man to that of a super inflated goblin." Gibbons wrote of the docility of the victims, who often lay within sight of small markets where supplies of food were on sale but "the pangs of hunger so far have not driven the starving hordes to storm the market place and take the food there displayed for themselves."

In an article published in New York Times on 3rd September, 1921, Gibbons wrote: "I talked with a doctor who saw a dog tearing the flesh from a dead man lying here in the market-place. The commandant of our train tells me of a woman with two children in her arms who threw herself under the train preceding ours. Women with puny weazened babies biting at their flat breasts wander through the streets, shouting wild gibberish, and with a wild light in their eyes. Every day the city authorities find rotting bodies in cellars, attics, lofts, sheds and out of the way places. where misery crawls away to gain the privilege of dying alone rather than in the midst of the city's filth and confusion.. It may be because they are too weak; maybe it is because starving men will not fight, for these men and women do not fight-not even the latter to save the lives of their children.... I witnessed no fight between any of the sufferers over food."

In another report he told the story of a young boy looking after his baby brother: "A boy of 12 with a face of sixty was carrying a six-month-old infant wrapped in a filthy bundle of furs. He deposited the baby under a freight car, crawled after him and drew from his pocket some dried fish-heads, which he chewed ravenously and then, bringing the baby's lips to his, transferred the sticky white paste of half-masticated fish-scales and bones to the infant's mouth as a mother bird feeds her young."

On his return to the United States he became a radio broadcaster. David Randall, the author of The Great Reporters (2005) has pointed out: "Being Gibbons he could not just broadcast as other folk. His trademark was an ability to speak faster than any other radio voice, and he was once recorded at a scarcely believable 217 words a minute. Somehow enough listeners understood the barrage for him to soon be receiving a thousand fan letters a day."

Gibbons published a biography of Manfred von Richthofen, entitled The Red Knight of Germany (1927). He also wrote a novel, The Red Napoleon (1929). Gibbons was given his own half-hour radio program on the NBC Radio Network. He was also the narrator for the documentary film With Byrd at the South Pole (1930).

Gibbons continued to report on world events. In 1934 he interviewed Benito Mussolini and in 1936 he covered the Spanish Civil War. His biographer pointed out: "He covered it from both sides, a project not without risk. But then, in the Spain of that time, almost any form of questioning and free expression was potentially lethal, as Gibbons discovered when he walked into a studio to broadcast and found it occupied by 12 loyalist soldiers armed not only with fixed bayonets but also orders to shoot him if he said anything against the Spanish Republic."

Floyd Gibbons died of a heart attack in September 1939 at the age of 52.

Primary Sources

(1) Floyd Gibbons, Chicago Tribune (25th February, 1917)

I have serious doubts whether this is a real story. I am not entirely certain that it is not all a dream and that in a few minutes I will wake up back in stateroom B19 on the promenade deck of the Cunarder Laconia and hear my cockney steward informing me with an abundance of "and sirs" that it is a fine morning.

It is now a little over thirty hours since I stood on the slanting decks of the big liner, listened to the lowering of the lifeboats, heard the hiss of escaping steam and the roar of ascending rockets as they tore lurid rents in the black sky and cast their red glare over the roaring sea.

I am writing this within thirty minutes after stepping on the dock here in Queenstown from the British mine sweeper which picked up our lifeboat after an eventful six hours of drifting and darkness and bailing and pulling on the oars and of straining aching eyes toward the empty, meaningless horizon in search of help. But, dream or fact, here it is:

The Cunard liner Laconia, 18,000 tons' burden, carrying seventy-three passengers; men, women, and children, of whom six were American citizens, manned by a mixed crew of 216, bound from New York to Liverpool, and loaded with foodstuffs, cotton, and raw material, was torpedoed without warning by a German submarine last night off the Irish coast. The vessel sank in about forty minutes.

Two American citizens, mother and daughter, listed from Chicago and former residents there, are among the dead.

The first cabin passengers were gathered in the lounge Sunday evening, with the exception of the bridge fiends in the smoke room.

"Poor Butterfly" was dying wearily on the talking machine, and several couples were dancing.

About the tables in the smoke room the conversation was limited to the announcement of bids and orders to the stewards. Before the fireplace was a little gathering which had been dubbed the Hyde Park corner - an allusion I don't quite fully understand. This group had about exhausted available discussion when I projected a new bone of contention.

"What do you say are our chances of being torpedoed?" I asked.

"Well," drawled the deliberative Mr Henry Chetham, a London solicitor, "I should say four thousand to one."

Lucien J. Jerome, of the British diplomatic service, returning with an Ecuadorian valet from South America, interjected: "Considering the zone and the class of this ship, I should put it down at two hundred and fifty to one that we don't meet a sub."

At this moment the ship gave a sudden lurch sideways and forward. There was a muffled noise like the slamming of some large door at a good distance away. The slightness of the shock and the meekness of the report compared with my imagination were disappointing. Every man in the room was on his feet in an instant.

"We're hit!" shouted Mr Chetham.

"That's what we've been waiting for," said Mr Jerome. "What a lousy torpedo!" said Mr Kirby in typical New Yorkese. "It must have been a fizzer."

I looked at my watch. It was 10:30 p.m.

Then came the five blasts on the whistle. We rushed down the corridor leading from the smoke room at the stern to the lounge, which was amid ship. We were running, but there was no panic.

The occupants of the lounge were just leaving by the forward doors as we entered...

The torpedo had hit us well astern on the starboard side and had missed the engines and the dynamos. I had not noticed the deck lights before. Throughout the voyage our decks had remained dark at night and all cabin portholes were clamped down and all windows covered with opaque paint...

Steam began to hiss somewhere from the giant gray funnels that towered above. Suddenly there was a roaring swish as a rocket soared upward from the captain's bridge, leaving a comet's tail of fire. I watched it as it described a graceful arc in the black void overhead, and then, with an audible pop, it burst in a flare of brilliant colors.

There was a tilt to the deck. It was listing to starboard at just the angle that would make it necessary to reach for support to enable one to stand upright. In the meantime electric floodlights - large white enameled funnels containing clusters of bulbs - had been suspended from the promenade deck and illuminated the dark water that rose and fell on the slanting side of the ship.

A hatchet was thrust into my hand and I forwarded it to the bow. There was a flash of sparks as it crashed down on the holding pulley. One strand of the rope parted and down plunged the bow, too quick for the stern man. We came to a jerky stop with the stern in the air and the bow down, but the stern managed to lower away until the dangerous angle was eliminated.

Then both tried to lower together. The list of the ship's side became greater, but, instead of our boat sliding down it like a toboggan, the taffrail caught and was held. As the lowering continued, the other side dropped down and we found ourselves clinging on at a new angle and looking straight down on the water.

Many feet and hands pushed the boat from the side of the ship, and we sagged down again, this time smacking squarely on the pillowy top of a rising swell. It felt more solid than mid-air, at least. But we were far from being off. The pulleys stuck twice in their fastenings, bow and stern, and the one ax passed forward and back, and with it my flashlight, as the entangling ropes that held us to the sinking Laconia were cut away.

Some shout from that confusion of sound caused me to look up, and I really did so with the fear that one of the nearby boats was being lowered upon us.

As we pulled away from the side of the ship, its receding terrace of lights stretched upward. The ship was slowly turning over. We were opposite that part occupied by the engine rooms. There was a tangle of oars, spars, and rigging on the seat and considerable confusion before four of the big sweeps could be manned on either side of the boat.

We rested on our oars, with all eyes on the still lighted Laconia. The torpedo had struck at 10:30 p.m., according to our ship's time. It was thirty minutes afterward that another dull thud, which was accompanied by a noticeable drop in the hulk, told its story of the second torpedo that the submarine had dispatched through the engine room and the boat's vitals from a distance of two hundred yards.

We watched silently during the next minute, as the tiers of lights dimmed slowly from white to yellow, then to red, and nothing was left but the murky mourning of the night, which hung over all like a pall.

A mean, cheese-colored crescent of a moon revealed one horn above a rag bundle of clouds in the distance. A rim of blackness settled around our little world, relieved only by general leering stars in the zenith, and where the Laconia's lights had shone there remained only the dim outline of a blacker hulk standing out above the water like a jagged headland, silhouetted against overcast sky.

The ship sank rapidly at the stern until at last its nose stood straight up in the air. Then it slid silently down and out of sight like a piece of disappearing scenery in a panorama spectacle.

(2) Sally J. Taylor, Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990)

Floyd Gibbons, now a dashing figure with his black eye patch, had chartered a plane and told Litvinov he planned to fly into Red Square in it, giving his paper a big scoop. Appalled at the prospect, Litvinov instead offered Gibbons the chance to go early into the area stricken by famine, exactly what Gibbons had been after all along. Once into the Ukraine, Gibbons sent his dispatches back by messenger and by train to Moscow, where they were cabled directly to the United States. In this way he gave his newspaper a ten-day lead on the others....

For the New York Times though, it was a case of having to buy what they had already paid for-and from a rival newspaper. And so Gibbons's first dispatch, copyrighted by the Chicago Tribune, appeared in the pages of the New York Times on the 1st of September 1921. In it, he described the empty streets and sidewalks of a small village inside the state of Samara. The people, he reported, were exhausted by malnutrition and no longer had the energy to go about the streets. Instead, they holed up inside their houses, eating cakes made from dried melon rinds which were ground up, then used as a kind of flour. The concoction provided no nourishment, only filled the stomachs of the starving. Hunger, Gibbons reported, had already claimed the lives of one-third of the inhabitants of the village."

(3) David Randall, The Great Reporters (2005)

In 1921 came his greatest triumph of all: the Russian Famine. Some time that summer, word began to leak out of the new Soviet state that people in their millions were starving in the Volga region. Checking these rumours was easier said than done. The Bolshevik government allowed no Western journalists to be based in Moscow, and coverage of the country was in the hands of reporters who hung around Riga's restaurants talking to emigres, White Russians and other unreliable witnesses. But as sketchy reports of a fearful famine gained momentum, so did interest in the story back home, and in mid-August Gibbons received this cable from Chicago: "Concentrate all available corrs on Russia. It is the greatest story in the world today. We must have first exclusive eye-witness report from corr on the spot." He sent two reporters, who soon joined all the other correspondents milling about Latvia waiting for permission to enter Russia. The Soviets were not letting them in; they wanted US food aid, but were afraid the full extent of the tragedy would be revealed. After the Tribune's men kicked their heels for a week, Chicago cabled Gibbons to go to Riga himself. Two days later he arrived - and was promptly arrested for landing without a visa. A bribe took care of that, and, once in town, he took the advice of colleague George Seldes and hatched a plan that might just get him into Russia. The rest of the press had dutifully filled out an application form for entry. Not Gibbons. Instead he told his German pilot to keep his plane primed for take-off, and let it be known around the bars that lie was thinking of making an illicit flight into Russia. Sure enough, informants picked up the story, and next day Gibbons was summoned to see Litvinov, the Soviet ambassador.

The meeting pitted the two wiliest brains in Riga against each other. Litvinov said he knew about Gibbons's plane, and warned him that if he tried to fly across the border he would be shot down. Gibbons countered by pointing out that the Russian border ran from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and anti-aircraft guns covered a mere traction of it. Litvinov then threatened to have Gibbons arrested, to which the reporter replied that the Soviets had just released all their US prisoners in order to secure food aid and were not likely to start incarcerating Americans again. Checkmate. That night, while the rest of the press fumed in Riga, Gibbons boarded a train for Moscow with Litvinov, and, after a few days in the capital, was on another train bound for the Volga. The ride took 40 hours, but the scene that greeted him in Samara was of such medieval degradation, it might as well have been a journey back through the centuries. So awful was the stench of death as he stepped from his carriage, and so high the risk of cholera and typhus, that he did his reporting with a towel soaked in disinfectant held to his face.

(4) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

The discomforts and difficulties of that first week in Moscow were envenomed for me and my colleagues by a purely professional matter. The Volga Famine was the biggest story of the year, but we sat there in Moscow fighting vermin and Soviet inertia; whilst Floyd Gibbons of the Chicago Tribune was cabling thousands of words a day from the Volga cities, beating our heads off and scoring one of the biggest newspaper triumphs in post-War history. Every day we received anguished and peremptory cables from our home offices about the Gibbons exploits, and all we could do was to run bleating with them to the Press Department and be told, "We are making arrangements; there will doubtless be a train for you tomorrow." It was an agonising experience, but there was nothing we could do about it but gnash our teeth and wait.

Floyd fully deserved his success because he had accomplished the feat of bluffing the redoubtable Litvinov stone-cold. It was a noble piece of work. As the Brown-Litvinov negotiations in Riga were drawing to a close, Floyd Gibbons arrived like a Herald Angel on a big private plane he had chartered in Berlin from a German pilot-owner, and made loud inquiries at the Lettish air headquarters for extra supplies of oil and fuel, concentrated foodstuffs and maps of Soviet Russia. Then he "went to ground" in a suite in Riga's best hotel. Meanwhile his minions - the Tribune had two or three men in Riga - went about muttering mysteriously of daring plans. Within three days the trick began to work, and Litvinov summoned Floyd to the Soviet Legation. "I learn," he said severely, "that you are contemplating an act of deplorable rashness." There was a gleam in Floyd's good eye, then it became as expressionless as the patch he wears over the other's empty socket, a souvenir of a German machine-gun bullet.

"I don't know what you're talking about," he said coldly.

Litvinov put a deprecating finger to his nose. "This is a small town," he said, "and we have ways of hearing things. Your secret has leaked out, Mr. Gibbons, and I know that you intend to fly to Moscow and try to land on the Red Square."

Floyd simulated confusion, but said nothing.

"Do you realise," continued Litvinov, pursuing his advantage, "that you will probably be met by a hail of bullets, and that if you should succeed in landing you will be immediately imprisoned?"

Floyd muttered something about a white flag and a friendly spirit.

"Nonsense," said Litvinov brusquely. "You cannot risk your life like this, and besides, it might create an unfortunate incident at this stage of the negotiations."Then I knew I had him," says Floyd, "and shot the works."

He spoke bitterly of secret agents tracking reporters and of his duty to the Tribune to be first with the news, of his contempt for personal danger and his determination to let no thought of risk interfere with his appointed mission. He was eloquent; and Litvinov was convinced. He believed that Floyd really meant to fly at once to Moscow. As it happened, he had just granted vises to two American correspondents of distinctly "pink" sympathies who were to leave the following day, without waiting, like the rest of the bourgeois reporters, for negotiations to end. He told this to Gibbons and added, "Suppose you went with them and abandoned your dangerous enterprise."

Floyd stuck it out. He would require the plane, he said, for visiting the Volga. In the Tribune's code, speed came first of all. Litvinov spoke hopefully of special trains, and Gibbons yielded with reluctance.

He reached Moscow a full week and the Volga ten days before the rest of us, and his exclusive stories of the Famine were reproduced in thirty-five countries of the world. Neither of his "pink" colleagues thought of sending back stuff by train and messenger from the places they visited or even from some of the larger cities by telegraph, as Gibbons did, to be retransmitted by cable from Moscow, and the frantic messages their offices sent them when Floyd's stuff was burning up the cables followed them two or three days late all along their journey.

"But would you have taken a chance on flying?" I asked Floyd afterwards.

"I would," he said cheerfully, "but when I hired that German plane in Berlin the pilot made an absolute stipulation that on no account would he fly over Soviet territory, not even across the edge. As it was I had to put up a bond of $5,000 before he would fly to Riga."

(5) Floyd Gibbons, New York Times (3rd September, 1921)

I talked with a doctor who saw a dog tearing the flesh from a dead man lying here in the market-place. The commandant of our train tells me of a woman with two children in her arms who threw herself under the train preceding ours. Women with puny weazened babies biting at their flat breasts wander through the streets, shouting wild gibberish, and with a wild light in their eyes. Every day the city authorities find rotting bodies in cellars, attics, lofts, sheds and out of the way places. where misery crawls away to gain the privilege of dying alone rather than in the midst of the city's filth and confusion...

It may be because they are too weak; maybe it is because starving men will not fight, for these men and women do not fight-not even the latter to save the lives of their children.... I witnessed no fight between

any of the sufferers over food.

(6) Floyd Gibbons, New York Times (6th September, 1921)

It was the first distribution of American relief in the Volga country, but we had no mistaken ideas about the good that it did. We could only feed that mite to some who had passed the food craving period and it would only renew the tortures that they had already gone through. We, who gave the bit of food, received more good from it than those who received it because in a measure it atoned for the fact we had in our bodies the warmth of ample food and were wearing whole clothes and were housed on a boat while 400 fellow-humans of our color and belief in our God were dying miserably within a stone's throw.