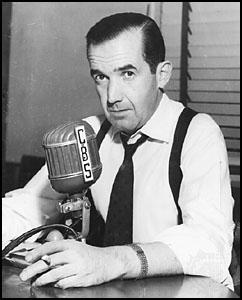

Edward Murrow

Edward Murrow, the son of Quakers,was born in Polecat Creek, Guildford County, on 25th April, 1908. Murrow attended Edison High School before studying at Washington State College. In 1932 he was appointed assistant director of the Institute of International Education.

Murrow joined the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) in 1935 as director of talks. His appointments included William L. Shirer in Germany. Two years later he was sent to London to arrange concerts for the radio network. He also made broadcasts about politics and in September 1938 he reported on the Munich Agreement signed by Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler: "Thousands of people are standing in Whitehall and lining Downing Street, waiting to greet the Prime Minister upon his return from Munich. Certain afternoon papers speculate concerning the possibility of the Prime Minister receiving a knighthood while in office, something that has happened only twice before in British history. Others say that he should be the next recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize."

Murrow was a critic of appeasement and on 2nd September, 1939, he argued: "Some people have told me tonight that they believe a big deal is being cooked up which will make Munich and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia look like a pleasant tea party. I find it difficult to accept this thesis. I don't know what's in the mind of the government, but I do know that to Britishers their pledged word is important, and I should be very much surprised to see any government which betrayed that pledge remain long in office. And it would be equally surprising to see any settlement achieved through the mediation of Mussolini produce anything other than a temporary relaxation of the tension."

Murrow remained in London after the outbreak of the Second World War and his eyewitness reports on the Blitz made him a national figure in the United States. On 10th September 1940 he reported: "We could see little men shovelling those fire bombs into the river. One burned for a few minutes like a beacon right in the middle of a bridge. Finally those white flames all went out. No one bothers about the white light, it's only when it turns yellow that a real fire has started. I must have seen well over a hundred fire bombs come down and only three small fires were started. The incendiaries aren't so bad if there is someone there to deal with them, but those oil bombs present more difficulties. As I watched those white fires flame up and die down, watched the yellow blazes grow dull and disappear, I thought, what a puny effort is this to burn a great city."

In May 1940 Winston Churchill became prime minister: "Winston Churchill, who has held more political offices than any living man, is now Prime Minister. He is a man without a party. For the last seven years he has sat in the House of Commons, a rather lonesome and often bellicose figure, voicing unheeded warnings of the rising tide of German military strength. Now, at the age of sixty-five, Winston Churchill, plump, bald, with massive round shoulders, is for the first time in his varied career of journalist, historian and politician the Prime Minister of Great Britain. Mr. Churchill now takes over the supreme direction of Britain's war effort at a time when the war is rapidly moving toward Britain's doorstep. Mr. Churchill's critics have said that he is inclined to be impulsive and, at times, vindictive. But in the tradition of British politics he will be given his chance. He will probably take chances. But if he brings victory, his place in history is assured."

During the Second World War Murrow flew on more than forty raids in Europe. He reported on 3rd December, 1943: "Berlin was a kind of orchestrated hell, a terrible symphony of light and flame. It isn't a pleasant kind of warfare - the men doing it speak of it as a job. Yesterday afternoon, when the tapes were stretched out on the big map all the way to Berlin and back again, a young pilot with old eyes said to me, "I see we're working again tonight."That's the frame of mind in which the job is being done. The job isn't pleasant; it's terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn't a pretty sight. In about thirty-five minutes it was hit with about three times the amount of stuff that ever came down on London in a night-long blitz. This is a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction.

In November 1944 Murrow reported on the new German weapon, the V-2 Flying Bombs: "I shall try to say something about V-2, the German rockets that have fallen on several widely scattered points in England. The Germans, as usual, made the first announcement and used it to blanket the fact that Hitler failed to make his annual appearance at the Munich beer cellar. The German announcement was exaggerated and inaccurate in some details, but not in all. For some weeks those of us who had known what was happening had been referring to these explosions, clearly audible over a distance of fifteen miles, as 'those exploding gas mains'. It is impossible to give you any reliable report on the accuracy of this weapon because we don't know what the Germans have been shooting at. They have scored some lucky and tragic hits, but as Mr. Churchill told the House of Commons, the scale and the effects of the attack have not hitherto been significant. That is, of course, no guarantee that they will not become so. This weapon carries an explosive charge of approximately one ton. It arrives without warning of any kind. The sound of the explosion is not like the crump of the old-fashioned bomb, or the flat crack of the flying bomb; the sound is perhaps heavier and more menacing because it comes without warning. Most people who have experienced war have been saved repeatedly by either seeing or hearing; neither sense provides warning or protection against this new weapon."

In 1945 Murrow moved to mainland Europe, first reporting the war from France and later in Germany. He was also with Allied troops when they entered the extermination camps at Buchenwald. "As I walked down to the end of the barracks, there was applause from the men too weak to get out of bed. It sounded like the hand clapping of babies; they were so weak. As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others - they must have been over sixty - were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it but will not describe it."

A prisoner commented: "You will write something about this, perhaps? "To write about this you must have been here at least two years, and after that - you don't want to write any more." Murrow continued to search the camp: "We proceeded to the small courtyard. The wall was about eight feet high; it adjoined what had been a stable or garage. We entered. It was floored with concrete. There were two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white.... It appeared that most of the men and boys had died of starvation; they had not been executed. But the manner of death seemed unimportant. Murder had been done at Buchenwald. God alone knows how many men and boys have died there during the last twelve years. Thursday I was told that there were more than twenty thousand in the camp. There had been as many as sixty thousand. Where are they now?" Murrow finished his report from Buchenwald with the words: "I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. If I've offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I'm not in the least sorry."

In the late 1940s Murrow supported the persecution of members of the American Communist Party. This included the arrest of its leaders, Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston and Gil Green under the Alien Registration Act. In sentenced to the men to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine (Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years). Murrow argued on 14th October 1949: "One result of the verdict may be to convince a number of people that the Communists are not just another political party. In view of the mass of evidence produced in judge Medina's court, it will be pretty difficult in the future for anyone to maintain that he joined and worked for the Communist Party without really knowing that it advocated violent revolution. There have been many serious proposals to control, contain or outlaw the Communist Party in this country, efforts to hog-tie them without strangling our liberties with the loose end of the rope. It is both delicate and dangerous business. We can't legislate loyalty. But nevertheless the question of the control of subversion is one of the most important confronting this country."

Murrow became concerned about the activities of Joseph McCarthy and suggested that his friend, Raymond Gram Swing, should debate with Ted C. Kirkpatrick, the co-author of Red Channels, at the Radio Executives Club on 19th October, 1950. Swing argued: "I shall be brief in giving the reasons why I believe the approach of Red Channels is utterly un-American. It is a book compiled by private persons to be sold for profit, which lists the names of persons for no other reason than to suggest them as having Communist connections of sufficient bearing to render them unacceptable to American radio. The list has been drawn up from reports, newspaper statements and letterheads, without checking, and without testing the evidence, and without giving a hearing to anyone whose name is listed. There is no attempt to evaluate the nature of the Communist connections. A number of organizations are cited as those with whom the person is affiliated, but with no statement as to the nature of the association."

In response to this speech, Kirkpatrick's magazine, Counterattack , published an article on Swing where it was claimed that: "The National Council of American Soviet Friendship was cited as subversive in 1947; in late 1948 he was still listed as one of its sponsors.. In his broadcasts Swing often followed an appeasement line and defended Russian policy." The magazine went on to attack an article he had written for the Atlantic Monthly where he had argued that the people of the United States "can choose whether to work with the Soviet Union as a partner or whether to surrender to memories and fears." As a result of these attacks, Swing was forced to resign the Voice of America (VOA).

In 1951 he inaugurated in-depth television journalism with his weekly, 30 minute, See It Now. He also presented Person to Person, where he interviewed well-known public figures. Murrow, like many other liberal journalists, became increasingly concerned about the impact that Joe McCarthy anti-communist campaign was having on America. He was particularly upset by the attacks on George Marshall, a man Murrow regarded as "the greatest living American". A friend of Murrow's, Larry Duggan, Director of the Institute of International Education (IIC), was also accused of being a member of the American Communist Party and ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Unwilling to name radicals he had associated with in his youth, Duggan committed suicide by jumping from his sixteenth-floor office.

Murrow now decided to speak out and complained about McCarthy's treatment of Henry Dexter White, who Joe McCarthy had recently accused of being a communist spy. Murrow was now accused of being part of the "Moscow conspiracy" and it was suggested that as "an anti-anti-Communist was as dangerous as a Communist".

In early 1954 Murrow and his producer, Fred Friendly, decided to devote an edition of See It Now to McCarthyism. CBS was unhappy with the idea and had been one of those television companies that had been part of the blacklist to prevent people named by Joe McCarthy from being employed in the industry. The CBS introduced its own "loyalty oath" contract and sacked some workers because they had previously been members of the Communist Party. CBS and the sponsor of the programme refused to publicize the proposed McCarthy programme, and as a result, Murrow and Friendly decided to use $1,500 their own money to pay for ads in the newspapers.

On 9th March, 1954, Murrow's See It Now programme, dealt with McCarthyism. During the broadcast Murrow commented: "The line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one and the junior Senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep into our own history and our doctrine and remember that we are not descended from fearful men, not men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes which were for the moment unpopular. This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthty's methods to keep silent. We can deny our heritage and our history, but we cannot escape responsibility for the result."

The day after the programme CBS announced that 12,348 people phoned in comments about the programme, and the opinions went fifteen-to-one in Murrow's favor. The sponsors also reported receiving over 4,000 letters, with the vast majority supporting Murrow's stance. The New York Herald Tribune, a Republican newspaper, said Murrow had presented "a sober and realistic appraisal of McCarthyism and the climate in which it flourishes." Jack Gould, television critic for The New York Times, called the broadcast "crusading journalism of high responsibility and genuine courage", an "incisive visual autopsy of the Senator's record'. However, Jack O'Brian, radio-TV columnist for Hearst's right-wing New York Journal-American, labelled the broadcast a "smear".

When Joe McCarthy was asked what he thought of the programme he replied: "I never listen to the extreme left-wing, bleeding heart elements of radio and TV." Several times over the next few days he attacked Murrow. He claimed that Murrow had "sponsored a communist school in Moscow" and "acted for the Russian espionage and propaganda organization known as VOKS, a job which would normally be done by the Russian secret police." He claimed that Murrow's friendship with Harold Laski, a leading figure in the British Labour Party, was an example of his pro-Communist sympathies.

The persecution of those opposed to McCarthyism continued. When the See It Now programme ended on 9th March, Don Hollenbeck, came on the air with the regular 11.00 p.m. news and said: "I want to associate myself with every word just spoken by Ed Murrow." Hollenbeck was denounced in the pro-McCarthy press as a communist. After three months of smears, Hollenbeck, unable to take the strain, committed suicide.

McCarthy's downfall came as a result of the televised senate investigations into the United States Army. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

In the late 1950s Murrow became disillusioned with television broadcasting. He disagreed with the emphasis being placed on producing entertainment-based programmes. Murrow left broadcasting in 1961 and joined the United States Information Agency (USIA). However, suffering from lung cancer, he was forced him to resign in 1964. The cancer spread to the brain and Edward Murrow died at Glen Arden, on 27th April, 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (30th September 1938)

Thousands of people are standing in Whitehall and lining Downing Street, waiting to greet the Prime Minister upon his return from Munich. Certain afternoon papers speculate concerning the possibility of the Prime Minister receiving a knighthood while in office, something that has happened only twice before in British history. Others say that he should be the next recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

International experts in London agree that Herr Hitler has scored one of the greatest diplomatic triumphs in modern history. The average Englishman, who really received his first official information concerning the crisis from Mr. Chamberlain's speech in the House of Commons on Wednesday, is relieved and grateful. Men who predicted the crisis and the lines it would follow long before it arrived did not entirely share that optimism and relief. One afternoon paper carried this headline: WORLD SHOWS

RELIEF - BUT WITH RESERVATIONS.

(2) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (28th August 1939)

I have a feeling that Englishmen are a little proud of themselves tonight. They believe that their government's reply was pretty tough, that the Lion has turned and that the retreat from Manchukuo, Abyssinia, Spain and Czechoslovakia and Austria has stopped. They are amazingly calm; they still employ understatement, and they are inclined to discuss the prospects of war with, oh, a casual "bad show", or, "If this is peace, give me a good war." I have heard no one say as many said last September, "I hope Mr. Chamberlain can find a way out."

There is not much thinking going on over here. People seem to revert to habit in times like this. Nothing seems to shake them. They lose the ability to feel. For instance, we had pictures in today's papers, pictures of school children carrying out a test evacuation. For them it was an adventure. We saw pictures of them tying on each other's identification tags, and they trooped out of the school building as though they were going to a picnic, and for them it was an adventure.

There is a feeling here that if Hitler does not back down, he will probably move against the Poles - not the French and British in the first instance. Then the decision must be made here and in France, and a terrible decision it will be. I will put it to you with the brutal frankness with which it was put to me by a British politician this afternoon: "Are we to be the first to bomb women and children?"

The military timetable has certainly been drawn up, but so far as we know in London the train for an unknown destination hasn't started. Within the last two hours, I have talked to men who have a certain amount of first-hand information as to the state of mind in Whitehall, and I may tell you that they see little chance of preserving peace. They feel that Herr Hitler may modify the demands, that the Italians may counsel against war, but they don't see a great deal of hope. And there the matter stands, and there it may stand until Parliament meets tomorrow in that small, ill-ventilated room where so many decisions have been made. I shall be there to report it to you.

Well, if it is to be war, how will it end? That is a question Englishmen are asking. And for what will it be fought, and what will be the position of the U.S.? Of course, that is a matter for you to decide, and you will reach your own conclusions in the light of more information than is available in any other country, and I am not going to talk about it. But I do venture to suggest that you watch carefully these moves during the next few days, that you further sift the evidence, for what you will decide will be important, and there is more than enough evidence that the machinery to influence your thinking and your decisions has already been set up in many countries.

And now, the last word that has reached London concerning tonight's developments is that at the British Embassy in Berlin all the luggage of the personnel and staff has been piled up in the hall, and it is remarked here that the most prominent article in the heavy luggage was a folded umbrella, given pride of placement amongst all the other pieces of baggage.

(3) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (2nd September 1939)

Some people have told me tonight that they believe a big deal is being cooked up which will make Munich and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia look like a pleasant tea party. I find it difficult to accept this thesis. I don't know what's in the mind of the government, but I do know that to Britishers their pledged word is important, and I should be very much surprised to see any government which betrayed that pledge remain long in office. And it would be equally surprising to see any settlement achieved through the mediation of Mussolini produce anything other than a temporary relaxation of the tension.

Most observers here agree that this country is not in the mood to accept a temporary solution. And that's why I believe that Britain in the end of the day will stand where she is pledged to stand, by the side of Poland in a war that is now in progress. Failure to do so might produce results in this country, the end of which cannot be foreseen. Anyone who knows this little island will agree that things happen slowly here; most of you will agree that the British during the past few weeks have done everything possible in order to put the record straight. When historians come to sum up the last six months of Europe's existence, when they come to write the story of the origins of the war, or of the collapse of democracy, they will have many documents from which to work. As I said, I have no way of ascertaining the real reason for the delay, nor am I impatient for the outbreak of war.

What exactly determined the government's decision is yet to be learned. What prospects of peaceful solution the government may see is to me a mystery. You know their record. You know what action they've taken in the past, but on this occasion the little man in the bowler hat, the clerks, the bus drivers, and all the others who make up the so-called rank and file would be reckoned with. They seem to believe that they have been patient, that they have suffered insult and injury, and they certainly believe that this time they are going to solve this matter in some sort of permanent fashion. Don't think for a moment that these people here aren't conscious of what's going on, aren't sensitive to the suspicions which the delay of their government has aroused. They're a patient people, and they're perhaps prepared to wait until tomorrow for the definite word. If that word means war, the delay was not likely to have decreased the intensity or the effectiveness of Britain's effort. If it is peace, with the price being paid by Poland, this government will have to deal with the passion it has aroused during the past few weeks. If it's a five-power conference, well, we shall see.

The Prime Minister today was almost apologetic. He's a politician; he sensed the temper of the House and of the country. I have been able to find no sense of relief amongst the people with whom I've talked. On the contrary, the general attitude seems to be, "We are ready, let's quit this stalling and get on with it." As a result, I think that we'll have a decision before this time tomorrow. On the evidence produced so far, it would seem that that decision will be war. But those of us who've watched this story unroll at close range have lost the ability to be surprised.

(4) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (10th May 1940)

History has been made too fast over here today. First, in the early hours this morning, came the news of the British unopposed landing in Iceland. Then the news of Hitler's triple invasion came rolling into London, climaxed by the German air bombing of five nations. British mechanized troops rattled across the frontier into Belgium. Then at nine o'clock tonight a tired old man spoke to the nation from No. 10 Downing Street. He sat behind a big oval table in the Cabinet Room where so many fateful decisions have been taken during the three years that he has directed the policy of His Majesty's government. Neville Chamberlain announced his resignation.

Winston Churchill, who has held more political offices than any living man, is now Prime Minister. He is a man without a party. For the last seven years he has sat in the House of Commons, a rather lonesome and often bellicose figure, voicing unheeded warnings of the rising tide of German military strength. Now, at the age of sixty-five, Winston Churchill, plump, bald, with massive round shoulders, is for the first time in his varied career of journalist, historian and politician the Prime Minister of Great Britain. Mr. Churchill now takes over the supreme direction of Britain's war effort at a time when the war is rapidly moving toward Britain's doorstep. Mr. Churchill's critics have said that he is inclined to be impulsive and, at times, vindictive. But in the tradition of British politics he will be given his chance. He will probably take chances. But if he brings victory, his place in history is assured.

The historians will have to devote more than a footnote to this remarkable man no matter what happens. He enters office with the tremendous advantage of being the man who was right. He also has the advantage of being the best broadcaster in this country. Mr. Churchill can inspire confidence. And he can preach a doctrine of hate that is acceptable to the majority of this country. That may be useful during these next few months. Hitler has said that the action begun today will settle the future of Germany for a thousand years. Mr. Churchill doesn't deal in such periods of time, but the decisions reached by this new prime minister with his boyish grin and his puckish sense of humour may well determine the outcome of this war.

(5) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (30th May 1940)

The battle around Dunkirk is still raging. The city itself is held by marines and covered by naval guns. The British Expeditionary Force has continued to fall back toward the coast and part of it, included wounded and those not immediately engaged, has been evacuated by sea. Certain units, the strength of which is naturally not stated, are back in England.

On the home front, new defence measures are being announced almost hourly. Any newspaper opposing the prosecution of the war can now be suppressed. Neutral vessels arriving in British ports are being carefully searched for concealed troops. Refugees arriving from the Continent are being closely questioned in an effort to weed out spies. More restrictions on home consumption and increased taxation are expected. Signposts are being taken down on the roads that might be used by German forces invading this country. Upon hearing about the signposts, an English friend of mine remarked, "That's going to make a fine shumuzzle. The Germans drive on the right and we drive on the left. There'll be a jolly old mix-up on the roads if the Germans do come."

One of the afternoon papers finds space to print a cartoon showing an elderly aristocratic Englishman, dressed in his anti-parachute uniform, saying to his servant, who holds a double-barrel shotgun, "Come along, Thompson. I shall want you to load for me." The Londoners are doing their best to preserve their sense of humour, but I saw more grave solemn faces today than I have ever seen in London before.

Fashionable tearooms were almost deserted; the shops in Bond Street were doing very little business; people read their newspapers as they walked slowly along the streets. Even the newsreel theatres were nearly empty. I saw one woman standing in line waiting for a bus begin to cry, very quietly. She didn't even bother to wipe the tears away. In Regent Street there was a sandwich man. His sign in big red letters had only three words on it: WATCH AND PRAY.

(6) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (2nd June 1940)

We are told today that most of the British Expeditionary Force is home from Flanders. There are no official figures of the number saved, but the unofficial estimates claim that as much as two thirds or perhaps four fifths of the force has been saved. It is claimed here that not more than one British division remains in the Dunkirk area. It may be that these estimates are unduly optimistic, but it's certainly true that a week ago few people believed that the evacuation could have been carried out so successfully.

There is a tendency on the part of some writers in the Sunday press to call the withdrawal a victory, and there will be disagreement on that point. But the least that can be said is that the Navy, Army and Air Force gilded defeat with glory. Military experts here agree that the operation has been the most successful in British military history. The withdrawal from Gallipoli during the last war does not compare with the removal of these troops from the pocket in northern France. The Gallipoli withdrawal was done in secrecy. There was no threat of air attacks. The action was spread over twenty-one nights. One hundred and twenty thousand men were removed at that time. During this Operation it is reliably reported that a considerably larger number was taken off in five days under incessant bombing and during the last two clays under long-range German artillery fire.

(7) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (18th August 1940)

I spent five hours this afternoon on the outskirts of London. Bombs fell out there today. It is indeed surprising how little damage a bomb will do unless, of course, it scores a direct hit. But I found that one bombed house looks pretty much like another bombed house. It's about the people I'd like to talk, the little people who live in those little houses, who have no uniforms and get no decorations for bravery. Those men whose only uniform was a tin hat were digging unexploded bombs out of the ground this afternoon. There were two women who gossiped across the narrow strip of tired brown grass that separated their two houses. They didn't have to open their kitchen windows in order to converse. The glass had been blown out. There was a little man with a pipe in his mouth who walked up and looked at a bombed house and said, "One fell there and that's all." Those people were calm and courageous. About an hour after the all clear had sounded, people were sitting in deck chairs on their lawns, reading the Sunday papers. The girls in light, cheap dresses were strolling along the streets. There was no bravado, no loud voices, only a quiet acceptance of the situation. To me those people were incredibly brave and calm. They are the unknown heroes of this war.

(8) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (10th October 1940)

For three hours after the night attack got going, I shivered in a sandbag crow's-nest atop a tall building near the Thames. It was one of the many fire-observation posts. There was an old gun barrel mounted above a round table marked off like a compass. A stock of incendiaries bounced off rooftops about three miles away. The observer took a sight on a point where the first one fell, swung his gun sight along the line of bombs and took another reading at the end of the line of fire. Then he picked up his telephone and shouted above the half gale that was blowing up there, "Stick of incendiaries - between 190 and 220 - about three miles away."

Five minutes later, a German bomber came boring down the river. We could see his exhaust trail like a pale ribbon stretched straight across the sky. Half a mile downstream there were two eruptions and then a third, close together. The first two looked like some giant had thrown a huge basket of flaming golden oranges high in the air. The third was just a balloon of fire enclosed in black smoke above the housetops. The observer didn't bother with his gun sight and indicator for that one. Just reached for his night glasses, took one quick look, picked up his telephone, and said, "Two high explosives and one oil bomb," and named the street where they had fallen.

There was a small fire going off to our left. Suddenly sparks showered up from it as though someone had punched the middle of a huge campfire with a tree trunk. Again the gun sight swung around, the bearing was read, and the report went down the telephone lines: "There is something in high explosives on that fire at 59."

There was peace and quiet inside for twenty minutes. Then a shower of incendiaries came down far in the distance. They didn't fall in a line. It looked like flashes from an electric train on a wet night, only the engineer was drunk and driving his train in circles through the streets. One sight at the middle of the flashes and our observer reported laconically, "Breadbasket at go - covers a couple of miles." Half an hour later a string of fire bombs fell right beside the Thames. Their white glare was reflected in the black, lazy water near the banks and faded out in midstream where the moon cut a golden swathe broken only by the arches of famous bridges.

We could see little men shovelling those fire bombs into the river. One burned for a few minutes like a beacon right in the middle of a bridge. Finally those white flames all went out. No one bothers about the white light; it's only when it turns yellow that a real fire has started.

I must have seen well over a hundred fire bombs come down and only three small fires were started. The incendiaries aren't so bad if there is someone there to deal with them, but those oil bombs present more difficulties. As I watched those white fires flame up and die down, watched the yellow blazes grow dull and disappear, I thought what a puny effort is this to burn a great city.

Finally we went below to a big room underground. It was quiet. Women spoke softly into telephones. There was a big map of London on the wall. Little coloured pins were being moved from one point to another and every time a pin was moved it meant that fire pumps were on their way through the black streets of London to a fire. One district had asked for reinforcements from another, just as an army reinforces its front lines in the sector bearing the brunt of the attack. On another map all the observation posts, like the one I just left, were marked. There was a string with a pin at the end of it dangling from each post position; a circle around each post bore the same markings as I had seen on the tables beneath the gun sight up above. As the reports came in, the string was stretched out over the reported bearing and the pin at the end stuck in the map. Another report came in, and still another, and each time a string was stretched. At one point all those strings crossed and there, checked by a half-dozen cross bearings from different points, was a fire. Watching that system work gave me one of the strangest sensations of the war. For I have seen a similar system used to find the exact location of forest fires out on the Pacific coast.

(9) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (22nd June 1940)

The Prime Minister brought all his oratorical power to the appeal for aid to the Soviet Union, which he has always hated - and still does. His plea was based on a combination of humanitarian principle and national self-interest. What he implied was that the Russians, after all, are human but the Germans aren't. Russia's danger, he said, is our danger. And he believed that the German plan was to destroy Russia in the shortest possible time and then throw her full weight against Britain in an attempt to crush this island before winter comes. And, reaffirming Britain's determination to destroy the Nazi regime, the Prime Minister promised that there would be no parley and no contract with Hitler and his gang. Any man or state who fights Nazidom will have our help, he said.

The announced policy of His Majesty's Government is to give the Russians all possible technical and economic assistance. Mr. Churchill said nothing about military aid, other than to reaffirm Britain's intention of bombing Germany on an ever-increasing scale. There is no suggestion in London that any direct military aid can, or will, be supplied. It is worth noting that the Prime Minister said nothing about the fighting qualities of the Russian Army and gave no optimistic forecast about the duration of this new German campaign.

A few days ago, Mr. Churchill in a broadcast to the States used the sentence: "But time is short." If Russia is beaten quickly and decisively, time will be much shorter.

(10) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (3rd December, 1943)

Berlin was a kind of orchestrated hell, a terrible symphony of light and flame. It isn't a pleasant kind of warfare - the men doing it speak of it as a job. Yesterday afternoon, when the tapes were stretched out on the big map all the way to Berlin and back again, a young pilot with old eyes said to me, "I see we're working again tonight." That's the frame of mind in which the job is being done. The job isn't pleasant; it's terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn't a pretty sight. In about thirty-five minutes it was hit with about three times the amount of stuff that ever came down on London in a night-long blitz. This is a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction.

(11) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (12th November 1944)

I shall try to say something about V-2, the German rockets that have fallen on several widely scattered points in England. The Germans, as usual, made the first announcement and used it to blanket the fact that Hitler failed to make his annual appearance at the Munich beer cellar. The German announcement was exaggerated and inaccurate in some details, but not in all. For some weeks those of us who had known what was happening had been referring to these explosions, clearly audible over a distance of fifteen miles, as "those exploding gas mains". It is impossible to give you any reliable report on the accuracy of this weapon because we don't know what the Germans have been shooting at. They have scored some lucky and tragic hits, but as Mr. Churchill told the House of Commons, the scale and the effects of the attack have not hitherto been significant.

That is, of course, no guarantee that they will not become so. This weapon carries an explosive charge of approximately one ton. It arrives without warning of any kind. The sound of the explosion is not like the crump of the old-fashioned bomb, or the flat crack of the flying bomb; the sound is perhaps heavier and more menacing because it comes without warning. Most people who have experienced war have been saved repeatedly by either seeing or hearing; neither sense provides warning or protection against this new weapon.

These are days when a vivid imagination is a definite liability. There is nothing pleasant in contemplating the possibility, however remote, that a ton of high explosive may come through the roof with absolutely no warning of any kind. The penetration of these rockets is considerably greater than that of the flying bomb, but the lateral blast effect is less. There are good reasons for believing that the Germans are developing a rocket which may contain as much as eight tons of explosives. That would be eight times the size of the present rocket, and, in the opinion of most people over here, definitely unpleasant. These rockets have not been arriving in any considerable quantity, and they have not noticeably affected the nerves or the determination of British civilians. But it would be a mistake to make light of this new form of bombardment. Its potentialities arc largely unknown. German science has again demonstrated a malignant ingenuity which is not likely to be forgotten when it comes time to establish controls over German scientific and industrial research. For the time being, those of you who may have family or friends in these "widely scattered spots in England" need not be greatly alarmed about the risks to which they are exposed.

(12) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from Buchenwald (15th April 1945)

As I walked down to the end of the barracks, there was applause from the men too weak to get out of bed. It sounded like the hand clapping of babies; they were so weak.

As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others - they must have been over sixty - were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it but will not describe it.

We went to the hospital; it was full. The doctor told me that two hundred had died the day before. I asked the cause of death; he shrugged and said, "Tuberculosis, starvation, fatigue, and there are many who have no desire to live."

Professor Richer said perhaps I would care to see the small courtyard. I said yes. He turned and told the children to stay behind. As we walked across the square I noticed that the professor had a hole in his left shoe and a toe sticking out of the right one. He followed my eyes and said, "I regret that I am so little presentable, but what can one do?" At that point another Frenchman came up to announce that three of his fellow countrymen outside had killed three S.S. men and taken one prisoner.

We proceeded to the small courtyard. The wall was about eight feet high; it adjoined what had been a stable or garage. We entered. It was floored with concrete. There were two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white. Some of the bodies were terribly bruised, though there seemed to be little flesh to bruise. Some had been shot through the head, but they bled but little. All except two were naked. I tried to count them as best I could and arrived at the conclusion that all that was mortal of more than five hundred men and boys lay there in two neat piles.

It appeared that most of the men and boys had died of starvation; they had not been executed. But the manner of death seemed unimportant. Murder had been done at Buchenwald. God alone knows how many men and boys have died there during the last twelve years. Thursday I was told that there were more than twenty thousand in the camp. There had been as many as sixty thousand. Where are they now?

As I left the camp, a Frenchman came up to me and said, "You will write something about this, perhaps?" And he added, "To write about this you must have been here at least two years, and after that - you don't want to write any more."

I pray you to believe what I have said about Buchenwald. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. If I've offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I'm not in the least sorry.

(13) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (16th September 1945)

I suppose that anyone can pose as an expert if he's far enough from home. I've been home for a little more than a week and haven't really seen anything except Washington and New York. But there has been time for a lot of reading and much listening and an astonishing amount of eating. The impressions created by this country at peace are so strong that I want to talk about them. It'll probably be old stuff to you, but it is at least possible that one who has spent a few years abroad, wondering what was happening in his own country, often longing to be there, might see or sense something that you have come to regard as commonplace. During the last few years I have tried to talk from various places in the world about something that was to me interesting and perhaps important. What is happening in America now is of tremendous importance to the rest of the world, and there's nothing that interests me more. So, with full knowledge that the impressions are superficial and may be mistaken, I should like - to use one of Mr. Churchill's favourite words - to "descant" for a few minutes upon the American scene.

You all look very, very healthy. You're not as tired as Europeans, and your clothes - well, it seemed to me for the first few days that everyone must be going to a party. The colour, the variety and, above everything else, the cleanliness of the clothing is most impressive. And what can be said about the food? The other morning, flying from Washington to New York, the hostess asked if I would care for breakfast. She brought fruit juice, scrambled eggs, bacon, rolls and coffee and cream and sugar. That meal in Paris would have cost about ten dollars; it would have been unobtainable in London.

(14) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (23rd September 1945)

I have been reading a thoughtful magazine article by a friend of mine, John Chamberlain. He deals with an event which affected the lives of all of us - the attack at Pearl Harbor and the events that led up to it. He concludes that valuable lessons can be learned as the result of a thorough-going investigation. That is probably true, for the people have a right to know what was done in their name. But Mr. Chamberlain states, "To say that we were slugged without warning is a radical distortion of the truth. Roosevelt, the chief executive of the nation and the commander-in-chief of its Army and Navy, knew in advance that the Japanese were going to attack us and," he adds, "there is even grounds for suspicion that he elected to bring the crisis to a head, when it came." And - Mr. Chamberlain continues, "More than fifteen hours before Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt and the members of the Washington high command knew that the Japanese envoys were going to break with the United States the next clay. The only thing they did not know was the precise point of the military attack."

These are serious charges and, presumably, will be investigated in due course. I should like to make some comment upon them. I dined at the White House on that Pearl Harbor Sunday evening. The President did not appear for dinner but sent word down that I was to wait. He required some information about Britain and the blitz, from which I had just returned. I waited. There was a steady stream of visitors - cabinet members and Senate leaders. In the course of the evening I had some opportunity to exchange a few words with Harry Hopkins and two or three cabinet members when they emerged from conference. There was ample opportunity to observe at close range the bearing and expression of Mr. [Henry L.] Stimson, Colonel [Frank] Knox, and Secretary [Cordell] Hull [secretaries of Army, Navy and State]. If they were not surprised by the news from Pearl Harbor, then that group of elderly men were putting on a performance which would have excited the admiration of any experienced actor. I cannot believe that their expressions, bearing and conversation were designed merely to impress one correspondent who was sitting outside in the hallway. It may be that the degree of the disaster had appalled them and that they had known for some time, as Mr. Chamberlain asserts, that Japan would attack, but I could not believe it then and I cannot do so now. There was amazement and anger written large on most of the faces.

Some time after midnight - it must have been nearly one in the morning - the President sent for me. I have seen certain statesmen of the world in time of crisis. Never have I seen one so calm and steady. He was completely relaxed. He told me much of the day's events, asked questions about how the people of Britain were standing up to their ordeal, inquired after the health of certain mutual friends in London. In talking about Pearl Harbor he was as much concerned about the aircraft lost on the ground as about the ships destroyed or damaged.

Just before I left, the President said, "Did this surprise you?" I replied, "Yes, Mr. President." And his answer was, "Maybe you think it didn't surprise us!" I believed him. He had told me enough of the day's disaster to know that there was no possibility of my writing a line about that interview till the war was over. I have ventured to recount part of that interview now because it seems to me to be, relevant to a current controversy.

(15) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (27th October 1947)

I want to talk for a few minutes about the Hollywood investigation now being conducted in Washington. This reporter approaches the matter with rather fresh memories of friends in Austria, Germany and Italy who either died or went into exile because they refused to admit the right of their government to determine what they should say, read, write or think. (If witnessing the disappearance of individual liberty abroad causes a reporter to be unduly sensitive to even the faintest threat of it in his own country, then my analysis of what is happening in Washington may be out of focus.) This is certainly no occasion for a defence of the product of Hollywood. Much of that product fails to invigorate me, but I am not obliged to view it. No more is this an effort to condemn congressional investigating committees. Such committees are a necessary part of our system of government and have performed in the past the double function of illuminating certain abuses and of informing congressmen regarding expert opinion on important legislation under consideration. In general, however, congressional committees have concerned themselves with what individuals, organizations or corporations have or have not done, rather than with what individuals think. It has always seemed to this reporter that movies should be judged by what appears upon the screen, newspapers by what appears in print and radio by what comes out of the loudspeaker. The personal beliefs of the individuals involved would not seem to be a legitimate field for inquiry, either by government or by individuals. When bankers, or oil or railroad men, are hailed before a congressional committee, it is not customary to question them about their beliefs or the beliefs of men employed by them. When a soldier is brought before a court martial he is confronted with witnesses, entitled to counsel and to cross-questioning. His reputation as a soldier, his prospects of future employment, cannot be taken from him unless a verdict is reached under clearly established military law.

It is, I suppose, possible that the committee now sitting may uncover some startling and significant information. But we are here concerned only with what has happened to date. A certain number of people have been accused either of being Communists or of following the Communist line. Their accusers are safe from the laws of slander and libel. Subsequent denials are unlikely ever to catch up with the original allegation. It is to be expected that this investigation will induce increased timidity in an industry not renowned in the past for its boldness in portraying the significant social, economic and political problems confronting this nation. For example, Willie Wyler, who is no alarmist, said yesterday that he would not now be permitted to make The Best Years of Our Lives in the way in which he made it more than a year ago.

Considerable mention was made at the hearings of two films, Mission to Moscow and Song of Russia. I am no movie critic, but I remember what was happening in the war when those films were released. While you were looking at Mission to Moscow there was heavy fighting in Tunisia. American and French forces were being driven back; Stalin said the opening of the Second Front was near; there was heavy fighting in the Solomons and New Guinea; MacArthur warned that the Japanese were threatening Australia; General Hershey announced that fathers would be called up in the draft; Wendell Willkie's book One World was published. And when Song of Russia was released, there was heavy fighting at Cassino and Anzio; the battleship Missouri was launched, and the Russian newspaper Pravda published, and then retracted, an article saying that the Germans and the British were holding peace talks. And during all this time there were people in high places in London and Washington who feared lest the Russians might make a separate peace with Germany. If these pictures, at that time and in that climate, were subversive, then what comes next under the scrutiny of a congressional committee?

Correspondents who wrote and broadcast that the Russians were fighting well and suffering appalling losses? If we follow the parallel, the networks and the newspapers which carried those dispatches would likewise be investigated.

Certain government agencies, such as the State Department and the Atomic Energy Commission, are confronted with a real dilemma. They are obligated to maintain security without doing violence to the essential liberties of the citizens who work for them. That may require special and defensible security measures. But no such problem arises with instruments of mass communication. In that area there would seem to be two alternatives: either we believe in the intelligence, good judgment, balance and native shrewdness of the American people, or we believe that government should investigate, intimidate and finally legislate. The choice is as simple as that.

The right of dissent - or, if you prefer, the right to be wrong - is surely fundamental to the existence of a democratic society. That's the right that went first in every nation that stumbled down the trail toward totalitarianism.

I would like to suggest to you that the present search for Communists is in no real sense parallel to the one that took place after the First World War. That, as we know, was a passing phenomenon. Those here who then adhered to Communist doctrine could not look anywhere in the world and find a strong, stable, expanding body of power based on the same principles that they professed. Now the situation is different, so it may be assumed that this internal tension, suspicion, witch hunting, grade labeling - call it what you like - will continue. It may well cause a lot of us to dig deep into both our history and our convictions to determine just how firmly we hold to the principles we were taught and accepted so readily, and which made this country a haven for men who sought refuge. And while we're discussing this matter, we might remember a little-known quotation from Adolf Hitler, spoken in Konigsberg before he achieved power. He said, "The great strength of the totalitarian state is that it will force those who fear it to imitate it."

(16) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (27th October 1948)

This reporter would attempt to say a few words about an old friend. They say he committed suicide. I don't know. Jan Masaryk was a man of great faith and great courage. Under certain circumstances he would be capable of laying down his life with a grin and a wisecrack. For more than two years he had hidden a heavy heart behind that big smile and his casual, sometimes irreverent, often caustic comment on world affairs. I knew Jan Masaryk well before, during and after the war. I say that, not in any effort to gain stature in your eyes, but rather as a necessary preface to what follows. I sat with him all night in his London embassy the night his country was sacrificed on the altar of appeasement at Munich. He knew it meant war, knew that his country and its people were doomed. But there was no bitterness in the man, nor was there resignation or defeat.

We talked long of what must happen in Europe, of the young men that would die and the cities that would be smashed to rubble. But Jan Masaryk's faith was steady. As I rose to leave, the grey dawn pressed against the windows. Jan pointed to a big picture of Hitler and Mussolini that stood on the mantle and said, "Don't worry, Ed. There will be dark days, and many men will die, but there is a God, and He will not let two such men rule Europe." He had faith, and he was a patriot, and he was an excellent cook. One night during the blitz he was preparing a meal in his little apartment. A bomb came down in the middle distance and rocked the building. Jan emerged from the kitchen to remark, "Uncivilized swine, the Germans. They have ruined my souffle."

I once asked him what his war aim was, and he replied, "I want to go home." He always knew that in a world where there is no security for little nations there is neither peace nor security for big nations. After the Munich betrayal, the British made a conscience loan to Czechoslovakia. Benes and Masaryk used a considerable part of the money to set up an underground news service. It was functioning when the Germans overran the country, and all during the war those two men were the best informed in London on matters having to do with Middle Europe. They had information out of Prague in a matter of hours from under the noses of the Germans. Jan Masaryk took to the radio, talking to his people, telling them that there was hope in the West, that Czechs and Slovaks would again walk that fair land as free men. When the war was over he went home. Certain that his country had to get along with the Russians or, as he used to say, `they will cat us up,' his faith in democracy was in no way diminished. He became foreign minister in a coalition government. As the Communist strength increased, Jan saw less and less of his friends when he came to this country. His music gave him no comfort; no more were there those happy late night hours with Masaryk playing the piano, hours of rich, rolling Czech and Slovak folk songs. I asked him why he didn't get out, come to this country where he had so many friends. He replied, "Do you think I enjoy what I am doing? But my heart is with my people. I must do what I can. Maybe a corpse but not a refugee."

Did he make a mistake in this last crisis? I do not know. He stayed with Benes. Who knows what pressures he was subjected to? It is unlikely that he could have altered the course of events. Perhaps it was in his mind that he could save some of his friends, some small part of liberty and freedom, by staying on as non-party foreign minister. I talked to him on the telephone on the third day of the crisis, before the Communists had taken over. He thought then that Benes would dissolve parliament, call a national election, and the Communist strength would decrease. It would appear that the Communists moved too fast.

Did the course of events during the last two weeks cause Masaryk to despair and take his life, or was he murdered? This is idle speculation. Both are possible. But somehow this reporter finds it difficult to imagine him flinging himself from a third-floor window, which, as I remember and as the news agencies confirm, is no more than thirty-five or forty feet above the flagged courtyard. A gun, perhaps poison or a leap from a greater height would have been more convincing. It may be, of course, that Jan Masaryk made the only gesture for freedom that he was free to make. Whichever way it was, his name with that of his father will be one to lift the hearts of men who seek to achieve or retain liberty and justice.

(17) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (8th April 1948)

And now let's examine the case of Mr. Leo Isaacson and his passport. First, the facts. Mr. Isaacson was recently elected to the House of Representatives from the Bronx. He was the candidate of the American Labour Party. He had the support of Mr. Henry Wallace. There have been no charges of corruption, intimidation or coercion in connection with the election. Representative Isaacson applied to the State Department for a passport. He said he planned to attend a conference on aid to Greece to be held in Paris. The State Department refused to issue the passport. A spokesman for the department said the conference will include members of committees which have been organized in most Eastern European countries for the purpose of furnishing material and moral assistance to the guerrilla forces in Greece. The spokesman recalled that the United Nations General Assembly had passed a resolution calling on Greece's northern neighbours to do nothing to assist the guerrilla forces. Our own government is assisting the government of Greece to maintain its sovereignty against attack from guerrilla forces. And so the State Department concluded that the issuance of a passport for Mr. Isaacson would not be in the interest of the government of the United States. Mr. Isaacson renewed his request for a passport and was again refused by Acting Secretary of State Lovett, again on the grounds that Isaacson's presence at the Paris conference would not be in the best interest of this country.

This is the first time a member of Congress has ever been denied a passport by our State Department. Mr. Isaacson has accepted the decision as final but says it is an example of the book-burning mentality which now controls our government. He further claims that the department is limiting what information he may gather and where he may go as a congressman in search of facts. Now, under the law, any American citizen may apply for a passport to any country, but the decision as to whether it will be issued is solely within the power of the Secretary of State. The secretary can refuse to issue a passport, and under the law he is not required to state his reasons. So there is no question that under the existing law the Department of State acted in a wholly legal manner in refusing to give Mr. Isaacson his passport. Generally the issuance of a passport is a purely routine matter, but in this case it was denied on the grounds that Mr. Isaacson's presence at the Paris meeting would not serve the interests of this country. This position has received editorial support from The New York Times, which has stated, "No citizen is entitled to go abroad to oppose the policies and the interests of his country." The case of Mr. Isaacson and his passport has not aroused any considerable controversy in Congress or in the press. Those are the facts of the case.

This reporter would like to suggest a few considerations that are relevant to it. Mr. Isaacson is a follower of Henry Wallace. Had he been permitted to go to Paris, he might well have been expected to make speeches critical of American policy, similar to those made by Mr. Wallace on his European trip. However, the thesis that no citizen is entitled to go abroad to oppose the policies of his own country can be expanded. By denying him a passport, he can be prevented from expressing those views in person. But should he likewise be prevented from expressing them in print or on the air? For example, should the Voice of America in its broadcast to Europe report that there is complete unity in this country in support of our foreign policy? If it does so, it would not be telling the truth, and confidence in the honesty of our statements would be reduced. Also, are we to ban the export of publications containing material critical of our foreign policy?

Another question is raised by this decision. It is this: Should a government department be given sole power to determine who shall be free to travel abroad? If it is deemed to be in the best interest of this country to prevent those who oppose our foreign policy from going abroad, would it not be better to pass a law? For the only protection an individual has against other individuals or against the State is law, duly passed by his elective representatives and tested in the courts.

(18) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast (3rd November 1948)

It would be possible to exhaust all the adjectives in the book in an effort to describe what happened yesterday - why it happened and what consequences may be expected to flow from the decision freely taken by the American people. For weeks and months, both the analysts and apologists will be busy examining the labour vote, the farm vote, the size of the total vote and the strategy of the two major parties. There will be many explanations-much second guessing, considerable sympathy for those whose high hopes of office and honours have been frustrated.

Not much of this outpouring will be significant, except insofar as it may serve to guide the conduct of future political campaigns.

I do not pretend to know why the people voted as they did, for the people are mysterious and their motives are not to be measured. This election result has freed us to a certain extent from the tyranny of those who tell us what we think, believe and will do without consulting us. No one, at this moment, can say with certainty why the Republicans lost or why the Democrats won. Certainly the Republicans did not lose for the lack of skilful, experienced, indeed, professional politicians. They did not lose for lack of money or energy. They lost because the people decided, in their wisdom or their folly, that they did not desire the party and its candidates to govern this country for the next four years. Maybe they lost because, as some claim, their policy was based upon expediency, rather than principle, or because they refrained from striking shrewd blows at points where the Democrats were vulnerable; maybe it was the labour vote that did them in, or the fact that the farmers are prosperous, or that too many Republicans were made complacent and didn't vote because of the predictions of easy victory. I do not know, and I do not think it matters, for the people are sovereign, and they have decided.

It will be equally difficult - indeed, more difficult - to explain the Democratic victory. President Truman was beaten to the floor by his own party even before they nominated him, and he got up, dressed in the ill-fitting cape of Franklin Roosevelt. He was a man who seemed unimpressive to many even when they thought he was right. He waged what was, in effect, a one-man campaign. Just try to call to mind the nationally known names who stood with him in this campaign, and you'll realize what a lonely (some said ridiculous) effort it was. He was just doing the best he knew how and saying so, and whatever the reasons, the people went with him and gave him a House and a Senate to work with.

(19) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast (14th October 1949)

Let's examine some of the implications of the verdict. The men were indicted under the Smith Act, which was passed in 1940. It went through the Senate without a roll call, and only four votes were registered against it in the House. The verdict in judge Medina's court will be tested before the Supreme Court, and that body will have to try to determine the constitutional limitations that may be placed upon advocacy of change through violence.

There are some things that can be concluded from the verdict: If you conspire, as these men were convicted of conspiring, then you face a prison sentence and possible fine. The verdict means that there will be a determined campaign by the Communists to try to sell to the country the issues that were lost in the trial. It means that the eleven Communist leaders aren't going to be available to direct the affairs of the party for some time. The question arises as to whether the men who replace them will also be guilty of breaking the law. They could not automatically be judged guilty by virtue of their membership or official position in the Communist Party. The government would have to produce evidence, witnesses, documents and bring them before a jury as they did in this case. The verdict undoubtedly means Russian propaganda efforts to discredit our system of justice. But the verdict proves that under that system of justice, the accused can get a nine months' trial, plus a jury to hear the case - even if they are, as Prosecutor McGohey stated, "professional revolutionists."

But there are some things that this verdict does not mean. It does not mean that membership in the Communist Party as such is illegal. The party is not outlawed. The verdict does not mean that you must read any specific books, talk as you will or peacefully assemble for any purpose other than to conspire to overthrow the government by force and violence. It does not mean that you are subject to legal action for saying things favourable to the Communist Party. Nothing in this verdict limits the citizen's right, by peaceful and lawful means, to advocate changes in the Constitution, to utter and publish praise of Russia, criticism of any of our political personalities or parties. You may, in short, engage in any action or agitation except that aimed at teaching or advocating the overthrow of the government by violence.

If this verdict is upheld by the Supreme Court, similar prosecutions may follow. But in each individual case it will be necessary for the government to prove, not only that the defendants were members of the Communist Party, but that they conspired to overthrow the government, and did so knowingly and wilfully.

One result of the verdict may be to convince a number of people that the Communists are not just another political party. In view of the mass of evidence produced in judge Medina's court, it will be pretty difficult in the future for anyone to maintain that he joined and worked for the Communist Party without really knowing that it advocated violent revolution. There have been many serious proposals to control, contain or outlaw the Communist Party in this country, efforts to hog-tie them without strangling our liberties with the loose end of the rope. It is both delicate and dangerous business. We can't legislate loyalty. But nevertheless the question of the control of subversion is one of the most important confronting this country.

(21) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (25th January 1950)

This morning Alger Hiss was sentenced to five years in prison for perjury. This afternoon the drama moved to Washington, to Secretary of State Acheson's press conference. The question was: "Mr. Secretary, have you any comment on the Alger Hiss case?" Mr. Acheson replied in these words: "Mr. Hiss's case is before the courts, and I think it would be highly improper for me to discuss the legal aspects of the case, or the evidence, or anything to do with the case. I take it the purpose of your question was to bring something other than that out of me." And then Mr. Acheson said, "I should like to make it clear to you that whatever the outcome of any appeal which Mr. Hiss or his lawyers may take in this case, I do not intend to turn my back on Alger Hiss. I think every person who has known Alger Hiss, or has served with him at any time, has upon his conscience the very serious task of deciding what his attitude is, and what his conduct should be. That must be done by each person, in the light of his own standards and his own principles. For me," said Mr. Acheson, "there is very little doubt about those standards or those principles. I think they were stated for us a very long time ago. They were stated on the Mount of Olives, and if you are interested in seeing them, you will find them in the twenty-fifth chapter of the Gospel according to St. Matthew, beginning at Verse 34."

We are reliably informed that Secretary Acheson knew the question was coming but had not discussed his answer with President Truman because he regarded it as a personal matter. When Mr. Acheson was up for confirmation before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he was questioned about Alger Hiss, said he was his friend and added, "My friendship is not easily given, and not easily withdrawn." He proved that today.

(22) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (11th April 1951)

No words of any broadcaster will add to, or detract from, General MacArthur's military stature. When the President relieved him of his commands at one o'clock this morning, a sort of emotional chain reaction began. It might be useful to examine some of the issues raised by this decision, for they are rather more important than the fate of a general, or a president, or a group of politicians.

Did the President have the constitutional power to fire General MacArthur? He did, without question; even the severest critics of his action admit this. One of the basic principles of our society is that the military shall be subject to civilian control. At the present time when, as a result of our rearmament programme, the military is exercising increasing influence and power in both domestic and international affairs, it is of some importance that that principle be maintained. It is a principle to which the over-whelming majority of professional soldiers subscribe.

There developed, over a period of months, a basic disagreement between General MacArthur on the one hand and the President, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the State Department and our European allies on the other as to how the war in Korea should be conducted; and, more importantly, a disagreement as to how, and where, the forces of the free world should be deployed to meet the threat of world Communism. General MacArthur was sent certain instructions, and he ignored or failed to obey them. Those orders, wise or foolish, came from his superiors. We as private citizens are entitled to agree or disagree with the policy and the orders, but so far as military men are concerned, the Constitution is quite specific. It doesn't say that a President must be a Republican or a Democrat, or even that he must be wise. It says that he is the commander-in-chief. There occurred an open and public clash between civilian and military authority. It was dramatic, and it was prolonged over a period of almost four months. What hung in the balance was not MacArthur's reputation as a soldier, or Truman's as a statesman, but rather the principle of civilian control of the military men and forces of this country. The issue has now been resolved. It is, as many have remarked, a personal tragedy for General MacArthur at the climax of a brilliant military career. But these matters must be viewed in perspective. Tragedy has also overtaken about fifty-eight thousand young Americans in Korea, and for about ten thousand of them it was permanent - before their careers began.

That war is still going on. Is there any reason to believe that General MacArthur's removal will increase the prospects of ending it? Some diplomats are inclined to hope it will. They point to the fact that the Communists have labelled MacArthur the number one aggressor and warmonger. But there is nothing in Communist doctrine to indicate that their policies are determined by the personalities of opposing generals, nothing to hint their objectives do not remain what they were.

(23) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (12th September 1951)

The team of Marshall and Lovett has been broken up. This combination served the nation in the Army, the State Department and the Department of Defence.

General Marshall has probably been talked over and at more than any living American. He was eulogized when he retired as Chief of Staff, again when he resigned as Secretary of State and now when he resigns from Defence. Probably no man in the last ten years has spent more time before Congressional committees. His record is too well known to merit repetition; and it may be safely assumed that he will not now engage, in full uniform, in parades, posturing and political polemics. He has served in the spotlight for a long time. The public has had repeated opportunity to weigh and measure him, and historians may conclude that his greatest contributions were made in peacetime rather than in war. General Marshall is a man who held himself erect, but with a loose rein - the most completely self-controlled man I have ever known, capable of sitting through a long speech or a committee hearing without moving a muscle, but at the same time there was no tension about him. He can reprimand the wandering and verbose informant by saying in a mild voice, "Would you mind repeating what you have just tried to say?" And he can now cultivate his garden in Leesburg, warmed in the autumn of his life by the respect and admiration of most of his fellow countrymen and the gratitude of millions of Europeans who were, by his vision and drive to action, saved from slavery.

Mr. Robert Lovett, his successor, has much of the General's quiet equanimity. He is an old hand at serving his government, with a built-in urge to get things done, having served as Assistant Secretary of War for Air, Undersecretary of State and Undersecretary of Defence. There is no doubt that his appointment will be confirmed by the Senate, and the small-calibre minds in Washington which delight in sniping at everyone who works for his country may well find Lovett as tough a target to hit as was Marshall.

(24) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (13th February 1953)

The execution date for the condemned atom spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, will be set on Monday. Federal Judge Irving Kaufman said today he didn't believe anything can be accomplished in too long a delay, "except bringing upon the prisoners mental anguish by instilling false hopes in them." Counsel for the Rosenbergs asked that the executions be delayed for a month or two. The judge said he had been harassed more than ever by various groups since the President denied the Rosenbergs' appeal for clemency. He said, "It is as if a signal had been given. I have received many telephone calls and telegrams and letters."

Alexander Kendrick cables from Vienna that today the whole Communist world opened an unbridled attack on the Eisenhower Administration in connection with the Rosenberg case. All Communist newspapers and radio stations called for world-wide agitation from what they called "democratic forces". All satellite newspapers and all Communist papers in West Europe led their front pages with the President's rejection of the clemency plea. The Communist line was that the Eisenhower Administration had started its term with a "cold-blooded double murder". One Vienna Communist paper said that the Jelke vice trial here in New York was being deliberately staged by the Administration in order to detract attention from the Rosenberg case. All stories reported as a matter of fact that the Rosenbergs are innocent and were convicted on framed testimony.

In France, the Communist papers, of course, followed suit, but the conservative and non-Communist papers were also highly critical. One said, "The correctness of Eisenhower's decision may not be questioned, but its wisdom is something else again. We had all hoped for clemency that would demonstrate democratic justice tempered by mercy." Another highly influential non-Communist French paper, Le Monde, front-pages an editorial saying, "A measure of clemency would not have endangered American security. The execution will not frighten Communist fanatics, who consider they have a holy mission to perform. It will only give them an extra theme of propaganda to exploit."

Judge Kaufman was obviously correct; a signal has been given. Totalitarian states, whether Communist or Fascist, know how to create and make use of martyrs. The Russians are using the Rosenbergs as expendable weapons of political warfare. And the Rosenbergs, who have refused to talk, are apparently still willing instruments of the conspiracy they once served. There has been no responsible claim here that the two defendants have not received every consideration and every opportunity provided under American law. No new evidence has been produced since their conviction.