Alastair Denniston

Alastair Denniston, the eldest child of James Denniston, a doctor, and his wife, Agnes Guthrie, was born in Greenock on 1st December 1881. Dr. Denniston was the GP in the seaside resort of Dunoon. However, he had contracted tuberculosis while working in Turkey in the 1870s. He was advised to make sea voyages, in the belief that the sea air would cleanse his lungs. Denniston decided to take up employment as a ship's doctor. However, this did not have the desired impact on his health and he died in 1892. (1)

He was educated at Bowdon College before continuing his studies in Bonn and Paris. (2) His son, Robin Denniston, points out: "These are the hidden years. There are no letters. Perhaps there are records in Paris. Where did he stay? Was it a lonely life? Who helped him? We shall never know. He certainly became a triligualist, able to compile a German grammar much used in British schools." (3)

In 1906 he began teaching at Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh. Three years later he became a teacher of foreign languages at the Royal Naval College on the Isle of Wight. A talented athlete, he played hockey for Scotland in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. (4) He was a talented sportsman and played tennis and golf to a high-stand for many years.

On the outbreak of the First World War he was recruited by the Admiralty. As he was fluent in German he was appointed to Naval Intelligence. He operated from Room 40 in the Admiralty and was involved in intercepting, decrypting, and interpreting naval staff German and other enemy wireless and cable communications. Denniston later pointed out: "There were never more than 40 people working full time shifts on the deciphering work... Cryptographers did not exist, so far as one knew. A mathematical mind was alleged to be the best foundation... As time went on, when assistance of a less skilled nature was urgently required to work for these self-trained cryptographers who knew German, ladies with a university education and wounded officers unfit for active service were brought in." (5) The great success of Room 40 OB was decrypting the notorious Zimmermann Telegram in 1917. (6)

Alastair Denniston - GCCS

During the war Alastair Denniston married Dorothy Mary Gilliat, who also worked in Room 40. Dorothy gave birth to one son and one daughter. In 1919 Denniston was selected to lead the country's peacetime cryptanalytical effort as head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). Winston Churchill, insisted that Denniston should be given the post: "We should only consent to pool our staff with that of the War Office on condition that Commander A. G. Denniston is placed in charge of the new Department.... Denniston is not only the best man we have had, but he is the only one we have left with special genius for this work." (7) In 1920 it was transferred from the Navy to the Foreign Office. (8) He was allowed by the Treasury to employ thirty civilian assistants (as the high-level staff were called) and about fifty clerks and typists.

Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Oliver Strachey, were two other senior figures in the organisation. (9) Francis Harry Hinsley has pointed out: "He (Denniston) supervised its formation as a small interdepartmental organization of twenty-five people recruited from Room 40 OB and its equivalent section in the War Office, MI1B. It included defectors from Russia, linguists, and talented amateurs of all kinds." (10)

Charles Langbridge Morgan joined the GCCS in October 1925: "Like many other recruits, I had heard of the job through a personal introduction - advertisement of posts was at that time unthinkable... I took an entrance exam which had been devised by Oliver Strachey, a former member of MI1b, and included a number of puzzles, such as filling in missing words in a mutilated newspaper article and simple mathematical problems calling for nothing more than arithmetic and a little ingenuity. I wasted a lot of time on these, thinking there must be some catch and so did not finish the paper. Nevertheless I got top marks." (11)

Denniston was one of the first to become aware that any future war, unlike the First World War, was going to be a war of movement. The development of mechanized vehicles in the 1920s and 1930s, whether on the ground or in the air, meant that they moved rapidly away from their bases and from each other. This problem was mainly solved by the development of radio communication during this period. It enabled a commander to communicate with his superiors, his men and his base, from wherever he might happen to be. However, this form of communication had a major disadvantage. It was impossible to be sure that your enemy could not hear what you were saying. In the vast majority of cases the secret communication of information was vital. This secrecy was achieved by cyphering.

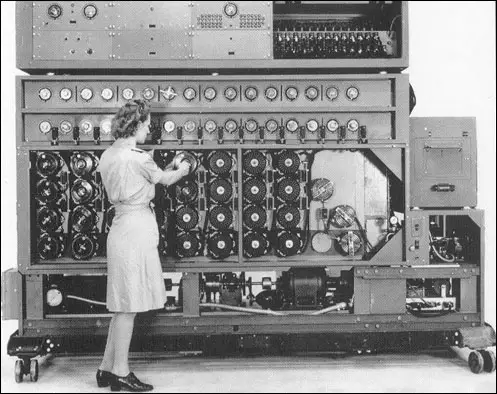

Enigma Machine

In 1926 Denniston purchased one of the original Enigma Machines developed by Arthur Scherbius. A version of the Enigma Machine was offered to the British Army but the apparatus was rejected as being "too ungainly for use in the field". The German Navy did purchase the machine and decided to adapt it for sending secret messages and in 1929 the German Army began using this improved version of Enigma. In Nazi Germany, the Luftwaffe, the Gestapo and the Schutzstaffel (SS) and vital services, like the railway system, also employed improved versions of the Enigma Machine.

The German government was convinced that by using the Enigma machine their military commanders would be able to communicate in secret. It became known as a transposition machine. That is to say, it turned every letter in a message into some other letter. The message stayed the same length but instead of being in German it became gobbledegook. The situation was explained by Francis Harry Hinsley: "By 1937 it was established that... the German Army, the German Navy and probably the Air Force, together with other state organizations like the railways and the SS used, for all except their tactical communications, different versions of the same cypher system - the Enigma machine which had been put on the market in the 1920s but which the Germans had rendered more secure by progressive modifications." (12)

As Peter Calvocoressi, the author of Top Secret Ultra (2001) has pointed out: "Over the years the Germans progressively altered and complicated the machine and kept everything about it more and more secret. The basic alterations from the commercial to the secret military model were completed by 1930/31 but further operating procedures continued to be introduced." (13)

One of the problems for Denniston is that he did not have the staff to deal with the increase of messages being sent by the German Army. This became an increasing problem during the Spanish Civil War. (14) In January 1937 he sent a memo to the Treasury pleading for more funds. "The situation in Spain... remains so uncertain that there is an actual increase in traffic to be handled since the height of the Ethiopian crisis, the figures for cables handled during the last three months of 1934, 1935 and 1936 being: 1934 (10,638); 1935 (12,696); 1936 (13,990). During the past month the existing staff has only been able to cope with the increase in traffic by working overtime." (15)

Alastair Denniston and Alan Turing

Denniston realised that in order to deal effectively with the increasing amount of secretly coded messages he had to recruit a number of academics to help with the work of the Government Code and Cypher School. One of Denniston's colleagues, Josh Cooper, told Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "He (Denniston) dined at several high tables in Oxford and Cambridge and came home with promises from a number of dons to attend a territorial training course. It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of this course for the future development of GCCS. Not only had Denniston brought in scholars of the humanities of the type of many of his own permanent staff, but he had also invited mathematicians of a somewhat different type who were especially attracted by the Enigma problem." (16)

Francis Harry Hinsley later claimed: "Denniston... recruited the wartime staff from the universities with visits there in 1937 and 1938 (also 1939 when he recruited me and 20 other undergraduates within two months of the outbreak of war). I believe this was a major contribution to the wartime successes - going to the right places and choosing the right people showed great foresight." (17) According to codebreaker, Mavis Batey, the mathematician, Alan Turing, went to one of the first of the training courses on codes and ciphers at Broadway Buildings. Turing was put on Denniston's "emergency list" for call up in event of war and was invited to attend meetings being held by top codebreaker, Alfred Dilwyn Knox to "hear about progress with Enigma, which immediately interested him... unusually, considering Denniston's paranoia about secrecy, it is said that Turing was even allowed" to take away important documents back to the university. (18)

Gordon Welchman worked at Sidney Sussex College when he was contacted by Denniston. He recalls in his book, The Hut Six Story (1982): "Between the wars, Denniston, seeing the strategic value of what he and his group were doing, had kept the Room 40 activity alive... Alastair Denniston planned for the coming war.... He decided that the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge would be his first source of recruits. So he visited them and arranged for polite notes to be sent to many lecturers, including myself, asking whether we would be willing to serve our country in the event of war." (19)

The recruitment and employment of skilled academics was expensive and so, once again, Denniston had to write to the Treasury to ask for financial assistance: "For some days now we have been obliged to recruit from our emergency list men of the Professor type with the Treasury agreed to pay at the rate of £600 a year. I attach herewith a list of these gentleman already called up together with the dates of their joining." (20) R. V. Jones, one of those academics who Denniston recruited, later claimed that his actions during this period "laid the foundations of our brilliant cryptographic success". (21)

Francis Harry Hinsley, the author of British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979-1990) has pointed out: "In 1937 Denniston had begun to recruit a number of dons who were to join GCCS on the outbreak of war. His contacts with academics who had been members of Room 40 OB helped him to choose such men as Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, who subsequently led the attack on Wehrmacht Enigma. Denniston's foresight, and his wise selection of the new staff, who for the first time included mathematicians, were the basis for many of GCCS's outstanding wartime successes, especially against Enigma... More than any other man, he helped it to maintain both the creative atmosphere which underlay its great contribution to British intelligence during the Second World War and the complete security which was no less an important precondition of its achievement." (22)

In June 1938, Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, received a message that the Polish Intelligence Service had encountered a man who had worked as a mathematician and engineer at the factory in Berlin where the Germans were producing the Enigma Machine. The man, Richard Lewinski (not his real name), was a Polish Jew who had been expelled from Nazi Germany because of his religion. He offered to sell his knowledge of the machine in exchange for £10,000, a British passport and a French resident permit. Lewinski claimed that he knew enough about Enigma to build a replica, and to draw diagrams of the heart of the machine - the complicated wiring system in each of its rotors.

Menzies suspected that Lewinski was a German agent who wanted to "lure the small British cryptographic bureau down a blind alley while the Germans conducted their business free from surveillance". Menzies suggested that Alfred Dilwyn Knox, a senior figure at the Government Code and Cypher School, should go to interview Lewinski. He asked Alan Turing to go with him. They were soon convinced that he had a deep knowledge of the machine and he was taken to France to work on producing a model of the machine.

According to Anthony Cave Brown, the author of Bodyguard of Lies (1976): "Lewinski worked in an apartment on the Left Bank, and the machine he created was a joy of imitative engineering. It was about 24 inches square and 18 inches high, and was enclosed in a wooden box. It was connected to two electric typewriters, and to transform a plain-language signal into a cipher text, all the operator had to do was consult the book of keys, select the key for the time of the day, the day of the month, and the month of the quarter, plug in accordingly, and type the signal out on the left-hand typewriter. Electrical impulses entered the complex wiring of each of the rotors of the machine, the message was enciphered and then transmitted to the right-hand typewriter. When the enciphered text reached its destination, an operator set the keys of a similar apparatus according to an advisory contained in the message, typed the enciphered signal out on the left-hand machine, and the right hand machine duly delivered the plain text. Until the arrival of the machine cipher system, enciphering was done slowly and carefully by human hand. Now Enigma, as Knox and Turing discovered, could produce an almost infinite number of different cipher alphabets merely by changing the keying procedure. It was, or so it seemed, the ultimate secret writing machine." (23)

The Polish replica of the Enigma Machine was taken to the Government Code and Cypher School. In early 1939 the CCCS arranged for Alan Turing to meet with Marian Rejewski and Henryk Zygalski, mathematicians who had been working for the Polish Cypher Bureau. He had been trying for seven years to understand the workings of the Enigma machine. They told Turing that he had come to the conclusion that as the code had been generated by a machine it could be broken by a machine. In Poland they had built a machine that they named "bomba kryptologiczna" or "cryptological bomb". This machine took over 24 hours to translate a German message on an Enigma machine. Turing was impressed by what Rejewski and Zygalski had achieved but realised that they must find a way of achieving this in a shorter time period if this breakthrough was to be effective. (24)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

On 25th July, 1939, Polish cryptologists held a meeting with French and British intelligence representatives in a meeting at Pyry, south of Warsaw. Britain was represented by Alastair Denniston and Alfred Dilwyn Knox. According to Mavis Batey, at first the Poles were reluctant to help the British because of their agreement with Adolf Hitler at Munich. (25) Eventually they importantly provided the information that Engima was breakable. Five weeks later the German Army invaded Poland. According to Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, the author of Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004), that without this information the substantial breaks into German Army and Air Force Enigma ciphers by the British would have occurred only after November 1941 at the earliest. (26)

The Second World War

On the outbreak of the Second World War the Government Code and Cypher School established Bletchley Park. This was selected because it was more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University and the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (27)

Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) has argued: "Alistair Denniston, had taken the precaution of surrounding himself with so many of the cryptography experts with whom he had worked since the First World War... He was a man of many talents... Judging by the many memos that he sent in his time at Bletchley Park, and which have now surfaced in the archives, he was also a man of uncommon patience, especially when dealing with volcanic, quirky or short-tempered colleagues." (28)

During the early stages of the war Denniston became aware of the deficiencies of the "need to know" policy, under which information is tightly compartmentalised, and only supplied to people who require it. As Ralph Erskine has pointed out that "need to know" policy carries a hidden flaw: "it assumes that is possible to know in advance who will require access to specific intelligence, yet that is completely impractical." As one codebreaker pointed out, he could not tell whether he needed anything until he had seen it. This included sharing information with other intelligence agencies. On 7th January, 1940, Turing had a meeting with codebreakers from Poland and France in Gretz-Armainvillers, near Paris. Turing learned "crucial information about rotors IV and V from the Poles, enabling him to solve its first Enigma key immediately after he returned." (29)

Turing's Machine

Alan Turing immediately began working on improving the Poles "bomba kryptologiczna". (Rejewski and Zygalski had escaped from Poland in September and were in hiding in France and eventually made their way to England, but they were too late to work on the project). To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (30)

The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. Gordon Welchman, one of the most important of the codebreakers, wrote in his book, The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes (1997), that Turing's machine "would never have gotten off the ground if we had not learned from the Poles, in the nick of time, the details both of the German military... Enigma machine, and of the operating procedures that were in use." (31)

Frederick Winterbotham was the chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (32)

A more improved version, called Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), was delivered on 8th August. From this point onwards, Bletchley Park was able to read, on a daily basis, every single Luftwaffe message - something in the region of one thousand a day. (33) At the time, the Battle of Britain was raging and the German codes were being broken at Bletchley Park, allowing the British to direct their fighters against incoming German bombers. When the battle was won the codebreakers intercepted messages cancelling the planned invasion of Britain - Operation Sealion. (34)

Employment of Women at GCCS

Keith Batey later recalled that Denniston liked appointing young women from upper-class families: "The first two girls (employed at GCCS) were the daughters of two chaps that Denniston played golf with at Ashtead. Denniston knew the family, he knew that they were nice people and... well, that their daughters wouldn't go around opening their mouths and saying what was going on. The background was so important if they were the sort of people who were not going to go around telling everyone what they were doing." (35)

Sarah Baring was the daughter of the Richard Henry Brinsley Norton, 6th Lord Grantley. At the beginning of the war Sarah and her friend, Osla Benning, went to work at the Hawker-Siddeley aircraft factory in Slough. (36) "When the war started, me and a great friend of mine, Osla Benning (Henniker-Major), decided we wanted to do something really important. And we thought: making aeroplanes.... We had to learn how to cut Durol, which the planes were made of. We did that for a while, and then Osla and I felt we weren't really doing enough." (37)

In 1941 Sarah and Osla, received a letter from the Foreign Office stating: "You are to report to Station X at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, in four days time." (38) Sarah later recalled: "Then suddenly, through the post, came a letter, God knows who from, asking us to report to the head of Bletchley - forthwith. That was all. So we thought: Anything's better than making aeroplanes at the moment." It seems that Lord Louis Mountbatten, her godfather, had put her name forward.

Denniston was persuaded by people like Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Gordon Welchman to employ women who had already distinguished themselves as mathematicians. Welchman, a mathematician from Sidney Sussex College, brought in Joan Clarke, who had graduated in 1939 from Newnham College with a double first in Mathematics. She worked with Alan Turing and eventually became Deputy Head of Hut 8. (39)

Knox, the senior cryptographer at Bletchley Park, and the man who has been described as "the mastermind" behind breaking the Enigma code, had a reputation for employing women. His unit was based in what was called the "Cottage" (in reality, a row of chunky converted interlinked houses - just across the courtyard from the main house, near the stables). (40)

Knox admitted that he liked employing women. According to Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010): "Dilwyn Knox... found that women had a greater aptitude for the work required - as well as nimbleness of mind and capacity for lateral thought, they possessed a care and attention to detail that many men might not have had." Two of the women in his unit, Mavis Batey and Margaret Rock, became important codebreakers. Mavis later recalled: "A myth has grown up that Dilly (Knox) went around in 1939 looking at the girls arriving at Bletchley and picking the most attractive for the Cottage.... That is completely untrue. Dilly took us on our qualifications." (41)

Knox was so impressed with the work of Mavis and Margaret that in August 1940, he contacted head office in an effort to get them a pay rise: "Miss Lever (later Mavis Batey) is the most capable and the most useful and if there is any scheme of selection for a small advancement in wages, her name should be considered.... Miss M. Rock is entirely in the wrong grade. She is actually 4th or 5th best of the whole Enigma staff and quite as useful as some of the 'professors'. I recommend that she should be put on to the highest possible salary for anyone of her seniority." (42)

Aileen Clayton, was one of the women at Bletchley Park who had dealings with Alastair Denniston. She later recalled in her book, The Enemy Is Listening (1980): "Station X... then under the control of Alastair Denniston, a quiet middle-aged man who seemed more like a professor than a naval officer. It was to him that I had to report, and I was immediately impressed by his kindness and by the courtesy with which he greeted me." (43)

Mavis Batey and Margaret Rock worked with Knox on the "updated Italian Naval Enigma machine, checking all new traffic and even the wheels, cogs and wiring to see how it was constructed." (44) In March 1941 Mavis deciphered a message, “Today 25 March is X-3". She later recalled that "if you get a message saying 'today minus three', then you know that something pretty big is afoot." Working with a team of intelligence analysts she was able to work out that the Italian fleet was planning to attack British troop convoys sailing from Alexandria to Piraeus in Greece. As a result of this information the British Navy was able to ambush four Italian destroyers and four cruisers off the coast of Sicily. Over 3,000 Italian sailors died during the Battle of Cape Matapan. Admiral John Henry Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence, sent a message to Bletchley Park: "Tell Dilly (Knox) that we have won a great victory in the Mediterranean and it is entirely due to him and his girls." (45)

Mavis and Margaret also played a very important role in breaking of the Enigma cipher used by the German secret service, the Abwehr. This was a vital aspect of what became known as the Double-Cross System (XX-Committee). Created by John Masterman, it was an operation that attempted to turn "German agents against their masters and persuaded them to cooperate in sending false information back to Berlin." (46) Masterman needed to know if the Germans believed the false intelligence they were receiving.

As the The Daily Telegraph later explained: "On December 8 1941 Mavis Batey broke a message on the link between Belgrade and Berlin, allowing the reconstruction of one of the rotors. Within days Knox and his team had broken into the Abwehr Enigma, and shortly afterwards Mavis broke a second Abwehr machine, the GGG, adding to the British ability to read the high-level Abwehr messages and confirm that the Germans did believe the phony Double-Cross intelligence they were being fed by the double agents." (47)

This was not the last of these women's breakthroughs. In February 1942, Mavis Batey solved the Enigma used by the Abwehr solely for communications between Madrid and several outstations situated around the Strait of Gibralter. Margaret Rock has been given credit for solving the Enigma being used by the Germans between Berlin and the Canaries in May 1943. (48)

Alastair Denniston leaves Bletchley Park

Alastair Denniston and his codebreakers achieved a substantial mastery of Enigma by the second half of 1941. His biographer, Francis Harry Hinsley, has pointed out: "GCCS... encountered new administrative requirements, and to an ever greater extent came to rely for its operation on specialized apparatus and machinery. Although Denniston recognized that these developments called for a major reorganization, he was not himself the man to carry it out: he had always been a reluctant administrator, preferring to concentrate on technical matters.... A reorganization in February 1942 divided GCCS into a services and a civil, and much smaller, wing, which had only about 250 staff (including its commercial section) by March 1944." (49) Commander Edward W. Travis now became head of services and Denniston remained the head of the civil division, moving to London in Berkeley Street, where, on seven floors, he and his team dealt with the diplomatic traffic of Germany, Italy, Japan, and many neutral countries.

Alastair Denniston worked very closely with Colonel Alfred McCormack, the influential deputy head of the US army's special branch, which supervised signal intelligence in the US war department. McCormack wrote on 2nd June 1943, that the "resources of intelligence… here in Denniston's show, waiting for somebody to tap them... he has ‘turned his people over to us (McCormack's team) for questioning and given us a free run of his place". (50)

William F. Friedman, who worked closely with Denniston during the Second World War and later became chief cryptologist for the National Security Agency (NSA) later told Denniston's daughter: "Your father was a great man in whose debt all English-speaking people will remain for a very long time, if not forever. That so few should know exactly what he did... is the sad part." (51)

Alastair Denniston: 1945-1961

Denniston retired in 1945 on an annual pension of £591 and thereafter taught French and Latin at a Leatherhead preparatory school. In 1958 his wife died of breast cancer and he went to live with his daughter Margaret and her husband, Geoffrey Finch, the local vicar in New Milton. (52)

Alastair Denniston died at the Memorial Hospital, Milford-on-Sea, Hampshire, on 1st January 1961. (53) His son, Robin Denniston, has pointed out that the national press did not comment on his death because of the Official Secrets Act and the media was unaware of his successful career. It was only after the government allowed Frederick Winterbotham, who had worked at Government Code and Cypher School during the war, to publish his book, The Ultra Secret (1974), that the general public became aware of Denniston's achievements.

George Steiner wrote in The Sunday Times on 23rd October, 1983, that increasingly "it looks as if Bletchley Park is the single greatest achievement of Britain during 1939-45, perhaps during this century as a whole". (54) However, it was not until 2001, that the man who masterminded Bletchley Park, obtained a brief entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (55)

The Imitation Game

The Imitation Game was released in 2014. An early scene shows Alan Turing being interviewed by Alastair Denniston, the head of the the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) at Bletchley Park. Denniston is portrayed by a man who has very little understanding of the people needed to "break" the Enigma Machine and is appalled by Turing's request for £100,000 to build a machine that will enable MI6 to read German secret messages. Denniston threatens to sack Turing but in a scene soon after this, he tells his codebreaker that he has friends in high places, as the prime minister, Winston Churchill, has agreed to make the £100,000, available to Turing. Churchill is therefore displayed as someone who had the brilliant foresight of realising that Turing was so talented that if he was given the money he would expose the secrets of Enigma. The scriptwriter, Graham Moore, from Los Angeles, was probably hoping that the audience was unaware that it was Neville Chamberlain who was prime minister in 1939. In fact, by the time Churchill became prime minister, Turing's machine, named "Victory", was already in operation at the GCCS. Turing never asked for £100,000, this figure is the cost when it reached GCCS.

In the film Denniston is shown as a self-righteous man with limited intelligence who sets out to obstruct Turing's codebreaking efforts. Charles Dance (the actor who plays the role of Commander Denniston) when interviewed about his role in the fim, actually described his character as a “pompous prat”. (56) In its efforts to communicate the message that Turing was a war hero, they decided they would try to destroy the reputation of Alastair Denniston, who undoubtedly was a great man who provided an important service to the nation in its time of need. Denniston constantly appears in the film as a symbol of the establishment that did not understand Turing genius. On one occasion he arrives with a posse of soldiers claiming that he is about to destroy his machine. Later, he turns up with the military police, who carry out a search of his office, because Denniston is convinced that Turing is a Soviet spy. This of course did not happen and from 1938 when Denniston brought him into the project, he was completely supportive of his work. I am all for filmmakers exposing incompetence in government agencies, however, it is disgraceful to make this kind of attack against a man who deserves to be fully respected by the British public.

On 26th November, 2014, Denniston's grandchildren wrote to The Daily Telegraph to complain about the portrayal of their grandfather. "While the much-acclaimed film The Imitation Game rightly acknowledges Alan Turing’s vital role in the war effort, it is sad that it does so by taking a side-swipe at Commander Alastair Denniston, portraying him as a mere hindrance to Turing’s work.... Cdr Denniston was one of the founding fathers of Bletchley Park. On his final visit to Poland in the summer of 1939, he was briefed by Polish mathematicians on the electrical equipment they had developed to break the German cipher machine, Enigma. The Enigma machine that Denniston took back to Bletchley ultimately allowed Britain to read the German High Command’s coded instructions. Such was the secrecy surrounding his work that his retirement in 1945, and death in 1961, passed virtually unnoticed, and he remains the only former head of GC&CS (the precursor to the intelligence agency GCHQ) never to have been awarded a knighthood. It was he who recruited Turing and many other leading mathematicians and linguists to Bletchley, where he fostered an environment that enabled these brilliant but unmanageable individuals to break the Enigma codes. The GCHQ of today owes much to the foundation he created there." (57)

Lady Brody, who worked with Alastair Denniston at Bletchley Park has commented: “As one of the few still alive who worked at Bletchley Park, I cannot believe that any of us would endorse the representation of Commander Alastair Denniston in the film The Imitation Game. When I encountered him he seemed a kindly and dedicated man. It is not time that the law of libel was changed to enable descendants to issue a writ when their forebears have been grossly misrepresented?” (58)

Primary Sources

(1) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story (1982)

Between the wars, Denniston, seeing the strategic value of what he and his group were doing, had kept the Room 40 activity alive. In 1920 the name of the organization was changed to "Government Code and Cypher School" (GCCS), and it was transferred from the Navy to the Foreign Office...

Alastair Denniston planned for the coming war. Following the example of his World War I chiefs, he decided that the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge would be his first source of recruits. So he visited them and arranged for polite notes to be sent to many lecturers, including myself, asking whether we would be willing to serve our country in the event of war. He chose Bletchley, 47 miles from London, as a wartime home for GCCS because it was a railway junction on the main line to the north from London's Euston Station and lay about halfway between Oxford and Cambridge with good train service to both. He acquired Bletchley Park, a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion with ample grounds. The house had been renovated by a prosperous merchant, who had introduced what Dilly Knox's niece, Penelope Fitzgerald, in her family memoir The Knox Brothers, was to call "majestic plumbing."

In the planning for the wartime Bletchley Park, Denniston's principal helpers, in Robin's recollection, were Josh Cooper, Nigel de Grey, John Tiltman, Admiral Sinclair's sister, and Sir Stuart Menzies. Edward Travis, whose later performance as successor to Alastair Denniston at Bletchley Park was so significant, must have been involved, but he was not one of the "family" team that dated back so many years. Robin believes that, before joining GCCS, Travis was involved in encipherment rather than codebreaking.

As preparatory work was being done, Denniston visited the site frequently, and made plans for construction of the numerous huts that would be needed in the anticipated wartime expansion of GCCS activities. When war actually came, these wooden huts were constructed with amazing speed by a local building contractor, Captain Hubert Faulkner, who was also a keen horseman and would often appear on site in riding clothes.

The word "hut" has many meanings, so I had better explain that the Bletchley huts were single-story wooden structures of various shapes and sizes. Hut 6 was about 30 feet wide and 60 feet long. The inside walls and partitions were of plaster board. From a door at one end a central passage, with three small rooms on either side, led to two large rooms at the far end. There were no toilets; staff had to go to another building. The furniture consisted mostly of wooden trestle tables and wooden folding chairs, and the partitions were moved around in response to changing needs.

The final move of the GCCS organization to Bletchley was made in August 1939, only a few weeks before war was declared. As security cover the expedition, involving perhaps fifty people, was officially termed "Captain Ridley's Hunting Party," Captain Ridley being the man in charge of general administration. The name of the organization was changed from GCCS to "Government Communications Headquarters" or GCHQ.

The perimeter of the Bletchley Park grounds was wired, and guarded by the RAF regiment, whose NCOs warned the men that if they didn't look lively they would be sent "inside the Park," suggesting that it was now a kind of lunatic asylum.

Denniston was to remain in command until around June 1940, when hospitalization for a stone in his bladder forced him to undertake less exacting duties. After his recovery he returned to Bletchley for a time before moving to London in 1941 to work on diplomatic traffic. Travis, who had been head of the Naval Section of GCCS and second in command to Denniston, took his place and ran Bletchley Park for the rest of the war. In recognition of his achievements he became Sir Edward Travis in 1942.

In spite of his hospitalization, Denniston, on his own initiative, flew to America in 1941, made contact with leaders of the cryptological organizations, and laid the foundations for later cooperation. He established a close personal relationship with the great American cryptologist William Friedman, who visited him in England later. The air flights were dangerous. On Denniston's return journey a plane just ahead of his and one just behind were both shot down.

(2) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983)

The director of GC and CS, Commander Alastair Denniston, was allowed by the Treasury to employ thirty civilian Assistants, as the high-level staff were called, and about fifty clerks and typists. For technical civil-service reasons, there were fifteen Senior and fifteen Junior Assistants. The Senior Assistants had all served in Room 40, except perhaps Feterlain, an exile from Russia who became head of the Russian section. There was Oliver Strachey, who was brother of Lytton Strachey and husband of Ray Strachey, the well-known feminist, and there was Dillwyn Knox, the classical scholar and Fellow of King's until the Great War. Strachey and Knox had both been members of the Keynesian circle at its Edwardian peak. The Junior Assistants had been recruited as the department expanded a little in the 1920s; the most recently appointed of them, A. M. Kendrick, had joined in 1932.

The work of GC and CS had played an important part in the politics of the 1920s. Russian intercepts leaked to the press helped to bring down the Labour government in 1924. But in protecting the British Empire from a revived Germany, the Code and Cypher School was less vigorous. There was a good deal of success in reading the communications of Italy and Japan, but the official history was to describe it as "unfortunate" that "despite the growing effort applied at GC and CS to military work after 1936, so little attention was devoted to the German problem."

One underlying reason for this was economic. Denniston had to plead for an increase in staff to match the military activity in the Mediterranean. In the autumn of 1935, the Treasury allowed an increase of thirteen clerks, although only on a temporary basis of six months at a time.

(3) Alastair Denniston, memo to the Treasury (January 1937)

The situation in Spain... remains so uncertain that there is an actual increase in traffic to be handled since the height of the Ethiopian crisis, the figures for cables handled during the last three months of 1934, 1935 and 1936 being: 1934 (10,638); 1935 (12,696); 1936 (13,990). During the past month the existing staff has only been able to cope with the increase in traffic by working overtime.

(4) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

In times of conflict, an island nation becomes uniquely vulnerable; if the enemy gains mastery over the seas, it will swiftly find ways to cut supplies of food and equipment to that island's shores. And it was immediately clear that the German navy, with its U-boats, would aim to strangle Britain's lifelines. It was for that reason that Bletchley Park's director, Alistair Denniston, had taken the precaution of surrounding himself with so many of the cryptography experts with whom he had worked since the First World War.

Commander Denniston was known by some as "the little man". A literal (and unkind) nickname referring to his short stature, it also obscured his many talents. He was trilingual; unusually, as a young man, he didn't go to a British university, attending instead the Sorbonne and Bonn University. Denniston had also been something of an athlete in his youth: he played hockey in the 1908 Olympics for the Scottish team. Judging by the many memos that he sent in his time at Bletchley Park, and which have now surfaced in the archives, he was also a man of uncommon patience, especially when dealing with volcanic, quirky or short-tempered colleagues.

(5) Francis Harry Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume One (1979-1990)

The volume of German wireless transmissions... was increasing; it was steadily becoming less difficult to intercept them at British stations; yet even in 1939, for lack of sets and operators, by no means all German Service communications were being intercepted. Nor was all intercepted traffic being studied. Until 1937-38 no addition was made to the civilian staff as opposed to the service personnel at GC and CS; and because of the continuing shortage of German intercepts, the eight graduates then recruited were largely absorbed by the same growing burden of Japanese and Italian work that had led to expansion of the Service sections.

(6) Letter from members of the Denniston family (Nick Denniston, Dr Susanna Everitt, Libby Buchanan, Judith Finch, Simon Finch, Alison Finch, Hilary Greenman and Candida Connolly) to The Daily Telegraph (26th November, 2014)

While the much-acclaimed film The Imitation Game rightly acknowledges Alan Turing’s vital role in the war effort, it is sad that it does so by taking a side-swipe at Commander Alastair Denniston, portraying him as a mere hindrance to Turing’s work.

We, his descendants, prefer to remember his extraordinary achievements in the First and Second World War, as well as his unstinting devotion to Britain’s security for more than 30 years. Cdr Denniston was one of the founding fathers of Bletchley Park. On his final visit to Poland in the summer of 1939, he was briefed by Polish mathematicians on the electrical equipment they had developed to break the German cipher machine, Enigma. The Enigma machine that Denniston took back to Bletchley ultimately allowed Britain to read the German High Command’s coded instructions.

Such was the secrecy surrounding his work that his retirement in 1945, and death in 1961, passed virtually unnoticed, and he remains the only former head of GC&CS (the precursor to the intelligence agency GCHQ) never to have been awarded a knighthood.

It was he who recruited Turing and many other leading mathematicians and linguists to Bletchley, where he fostered an environment that enabled these brilliant but unmanageable individuals to break the Enigma codes. The GCHQ of today owes much to the foundation he created there.

(7) Hannah Furness, The Daily Telegraph (26th November, 2014)

The family of Cdr Alastair Denniston claims the film takes an "unwarranted sideswipe" at his memory, showing him to be a "hectoring character" who hinders the work of Alan Turing, the codebreaker and computer science pioneer played by Benedict Cumberbatch.

In real life, relatives say, he was a "humble" man devoted to his work, and they want his true contribution to the war effort to be recognised.

Denniston, who died in 1961, was a cryptologist during the First World War. He continued in the Government Code and Cypher School - the forerunner of GCHQ - afterwards and moved his team to Bletchley Park at the outbreak of the Second World War.

There, he was responsible for hiring the mathematicians who went on to crack the Enigma code, including Turing.

Denniston is played in The Imitation Game by Charles Dance and comes into conflict with his team of mathematicians. In one scene, he is shown interrogating Turing as he weighs up whether to employ him. Dance described his character in an interview as a “pompous prat”.

Denniston’s descendants, who have seen the film but were not consulted during its research, are disappointed at how he has been portrayed, arguing he was unfairly turned into the film’s “baddy”.

After being made aware of the family’s distress, filmmakers emphasised The Imitation Game showed merely the “natural conflict of people working extremely hard under unimaginable pressure” and paid tribute to “one of the great heroes of Bletchley Park”.

In a letter to The Daily Telegraph today, seven of Denniston’s grandchildren and his god-daughter pay tribute to his memory, saying GCHQ “owes much to the foundation he created”. They say: “While the much-acclaimed film The Imitation Game rightly acknowledges Alan Turing’s vital role in the war effort, it is sad that it does so by taking an unwarranted sideswipe at Cdr Alastair Denniston, portraying him as a hectoring character who merely hindered Turing’s work.”

Nick Denniston, Cdr Denniston’s grandson, said that those who knew him well had been “deeply offended” by his portrayal, adding that there had been “quite a lot of bitterness” about his public legacy. He said: “Everyone that knew him saw him in a very different light.”

Libby Buchanan, Denniston’s 91-year-old niece and god-daughter, said she recalled a “quiet, dignified” man who was devoted to his work.

Judith Finch, his granddaughter, added: “He is completely misrepresented. They needed a baddy and they’ve put him in there without researching the truth about the contribution he made.”

The film’s writer, Graham Moore, and producers said: “Cdr Denniston was one of the great heroes of Bletchley Park.

“As such, he had the perhaps unenviable position of being a layman overseeing the work of some of the century’s finest mathematicians and academics - a situation bound to result in conflict as to how best to get the job done.“I would say that this is the natural conflict of people working extremely hard under unimaginable pressure with the fate of the war resting on their heroic shoulders.”

References

(1) Robin Denniston, Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 7

(2) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(3) Robin Denniston, Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 12

(4) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(5) Alastair Denniston, Room 40: 1914-15 (1919)

(6) Michael Smith, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 11

(7) Winston Churchill, letter to Henry Charles Ponsonby Moore, 10th Earl of Drogheda (28th March, 1919)

(8) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story (1982) page 8

(9) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) page 186

(10) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(11) Charles Langbridge Morgan, quoted by Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 12

(12) Francis Harry Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume One (1979-1990) page 53

(13) Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra (1980) page 31

(14) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) page 186

(15) Alastair Denniston, memo to the Treasury (January, 1937)

(16) Michael Smith, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 16

(17) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Robin Denniston, the author of Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 24

(18) Mavis Batey, Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page 71

(19) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story (1982) page 10

(20) Alastair Denniston, memo to the Treasury (September, 1937)

(21) R. V. Jones, Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945 (1978) page 98

(22) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(23) Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies (1976) page 21

(24) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 55

(25) Mavis Batey, Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page 69

(26) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004)

(27) Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (2002) page 228-229

(28) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 38

(29) Ralph Erskine, introduction to Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page xiii

(30) Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies (1976) page 23

(31) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes (1997)

(32) Frederick Winterbotham, The ULTRA Secret (1974) page 15

(33) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 98

(34) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 58

(35) Keith Batey, quoted by Sinclair McKay, in his book, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 22

(36) The Daily Mail (4th June, 2011)

(37) Sarah Baring, quoted by Sinclair McKay, in his book, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 25

(38) The Daily Telegraph (15th February, 2013)

(39) Lynsey Ann Lord, Joan Clarke Murray (2008)

(40) Mavis Batey, Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page 107

(41) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 57

(42) Alfred Dilwyn Knox, letter to Headquarters (August 1940)

(43) Aileen Clayton, The Enemy Is Listening (1980) page 98

(44) Martin Childs, The Independent (24th November 2013)

(45) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 132

(46) Richard Deacon, Spyclopaedia (1987) page 178

(47) The Daily Telegraph (13th November, 2013)

(48) Mavis Batey, Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page 211

(49) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(50) Colonel Alfred McCormack, report to Headquarters (2nd June 1943)

(51) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story (1982) page 11

(52) Robin Denniston, Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 8

(53) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(54) George Steiner, The Sunday Times (23rd October, 1983)

(55) Robin Denniston, Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 8

(56) Alex Ritman, The Hollywood Reporter (28th November, 2014)

(57) Letter from members of the Denniston family (Nick Denniston, Dr Susanna Everitt, Libby Buchanan, Judith Finch, Simon Finch, Alison Finch, Hilary Greenman and Candida Connolly) to The Daily Telegraph (26th November, 2014)

(58) Hannah Furness, The Daily Telegraph (7th December, 2014)