Enigma Machine

On 23rd February 1918, Arthur Scherbius, a German electrical engineer, patented an invention for a mechanical cipher machine based on rotating wired wheels. Later that year he established a company called Scherbius & Ritter and in 1923 they began selling the cypher machine under the name "Enigma". It was a commercial machine which anybody could buy. It was used by a few banks but it was a commercial failure. (1)

In 1926 Alastair Denniston, the head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) purchased an Enigma machine and it was demonstrated at the Foreign Office. It was offered to the British Army but it was rejected as being "too ungainly for use in the field". The German Navy also purchased the machine and decided to adapt it for sending secret messages. However, Scherbius was unable to benefit from these increased sales as he was killed in a horse carriage accident in 1929. (2)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

In 1929 the German Army began using this improved version of Enigma. So did the Luftwaffe, the Gestapo and the Schutzstaffel (SS) and other services like the railways in Nazi Germany. As Peter Calvocoressi, the author of Top Secret Ultra (2001) has pointed out: "Over the years the Germans progressively altered and complicated the machine and kept everything about it more and more secret. The basic alterations from the commercial to the secret military model were completed by 1930/31 but further operating procedures continued to be introduced." (3)

German Army & the Enigma Machine

German military commanders became aware that the Enigma Machine was going to play an important role in the forthcoming war. Unlike the First World War the Second World War was going to be a war of movement. The development of mechanized vehicles in the 1920s and 1930s, whether on the ground or in the air, meant that they moved rapidly away from their bases and from each other.

This problem was mainly solved by the development of radio communication during this period. It enabled a commander to communicate with his superiors, his men and his base, from wherever he might happen to be. However, this form of communication had a major disadvantage. It was impossible to be sure that your enemy could not hear what you were saying. In the vast majority of cases the secret communication of information was vital. This secrecy was achieved by cyphering.

A cypher is simply a way of making nonsense of a text to everybody who does not have a key to it. The Romans were the first to use ciphers (they called it secret writing). Julius Caesar sent messages to his fellow commanders in a code that they had agreed before the battle took place. (4) Suetonius tells us that Caesar simply replaced each letter in the message with the letter that is three places further down the alphabet. A cypher is the name given to any form of cryptographic substitution in which each letter is replaced by another letter or symbol. (5)

This type of cypher is easily broken and by the 1930s the intelligence services of the various countries were involved in developing a system that would be "unbreakable". The German government was convinced that by using the Enigma machine their military commanders would be able to communicate in secret. It was what became known as a transposition machine. That is to say, it turned every letter in a message into some other letter. The message stayed the same length but instead of being in German it became gobbledegook.

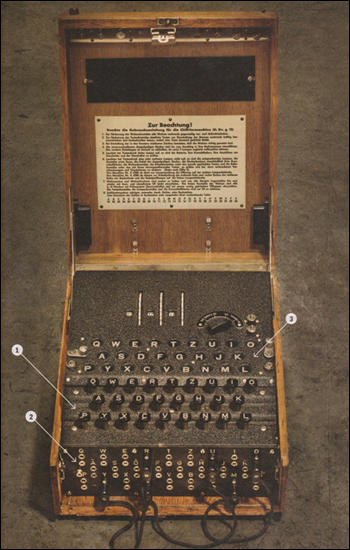

(2) Settings on the plugboard, in combination with the three rotors at the top,

determined the code. (3) With each key press, the corresponding coded (or decoded)

letter lit up on the output panel, allowing the operator to copy down the message.

The situation was explained by Francis Harry Hinsley: "By 1937 it was established that... the German Army, the German Navy and probably the Air Force, together with other state organizations like the railways and the SS used, for all except their tactical communications, different versions of the same cypher system - the Enigma machine which had been put on the market in the 1920s but which the Germans had rendered more secure by progressive modifications." (6)

One of the problems for Denniston is that he did not have the staff to deal with the increase of messages being sent by the German Army. This became an increasing problem during the Spanish Civil War. (7) In January 1937 he sent a memo to the Treasury pleading for more funds. "The situation in Spain... remains so uncertain that there is an actual increase in traffic to be handled since the height of the Ethiopian crisis, the figures for cables handled during the last three months of 1934, 1935 and 1936 being: 1934 (10,638); 1935 (12,696); 1936 (13,990). During the past month the existing staff has only been able to cope with the increase in traffic by working overtime." (8)

Alastair Denniston

Alastair Denniston realised that in order to deal effectively with this problem he had begun to recruit a number of academics to help work with the Government Code and Cypher School. This included people like Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman. One of Denniston's colleagues, Josh Cooper, told Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "He (Denniston) dined at several high tables in Oxford and Cambridge and came home with promises from a number of dons to attend a territorial training course. It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of this course for the future development of GCCS. Not only had Denniston brought in scholars of the humanities of the type of many of his own permanent staff, but he had also invited mathematicians of a somewhat different type who were especially attracted by the Enigma problem." (9)

According to codebreaker, Mavis Batey, Turing went to one of the first of the training courses on codes and ciphers at Broadway Buildings. Turing was put on Denniston's "emergency list" for call up in event of war and was invited to attend meetings being held by top codebreaker, Alfred Dilwyn Knox to "hear about progress with Enigma, which immediately interested him... unusually, considering Denniston's paranoia about secrecy, it is said that Turing was even allowed" to take away important documents back to the university. (10)

The recruitment and employment of skilled academics was expensive and so, once again, Denniston had to write to the Treasury to ask for financial assistance: "For some days now we have been obliged to recruit from our emergency list men of the Professor type with the Treasury agreed to pay at the rate of £600 a year. I attach herewith a list of these gentleman already called up together with the dates of their joining." (11) R. V. Jones, one of those academics who Denniston recruited, later claimed that his actions during this period "laid the foundations of our brilliant cryptographic success". (12)

Francis Harry Hinsley, the author of British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979-1990) has pointed out: "In 1937 Denniston had begun to recruit a number of dons who were to join GCCS on the outbreak of war. His contacts with academics who had been members of Room 40 OB helped him to choose such men as Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, who subsequently led the attack on Wehrmacht Enigma. Denniston's foresight, and his wise selection of the new staff, who for the first time included mathematicians, were the basis for many of GCCS's outstanding wartime successes, especially against Enigma... More than any other man, he helped it to maintain both the creative atmosphere which underlay its great contribution to British intelligence during the Second World War and the complete security which was no less an important precondition of its achievement." (13)

MI6 and Enigma Machine

The British intelligence services knew that the only way they would be able to break the code was to get hold of a German Enigma machine. In June 1938, Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, received a message that the Polish Intelligence Service had encountered a man who had worked as a mathematician and engineer at the factory in Berlin where the Germans were producing the Enigma machine. The man, Richard Lewinski (not his real name), was a Polish Jew who had been expelled from Nazi Germany because of his religion. He offered to sell his knowledge of the machine in exchange for £10,000, a British passport and a French resident permit. Lewinski claimed that he knew enough about Enigma to build a replica, and to draw diagrams of the heart of the machine - the complicated wiring system in each of its rotors.

Menzies suspected that Lewinski was a German agent who wanted to "lure the small British cryptographic bureau down a blind alley while the Germans conducted their business free from surveillance". Menzies suggested that Alfred Dilwyn Knox, a senior figure at the Government Code and Cypher School, should go to interview Lewinski. He asked Alan Turing, a mathematician from Cambridge University, who had being doing research into codebreaking, to go with him. They were soon convinced that he had a deep knowledge of the machine and he was taken to France to work on producing a model of the machine.

According to Anthony Cave Brown, the author of Bodyguard of Lies (1976): "Lewinski worked in an apartment on the Left Bank, and the machine he created was a joy of imitative engineering. It was about 24 inches square and 18 inches high, and was enclosed in a wooden box. It was connected to two electric typewriters, and to transform a plain-language signal into a cipher text, all the operator had to do was consult the book of keys, select the key for the time of the day, the day of the month, and the month of the quarter, plug in accordingly, and type the signal out on the left-hand typewriter. Electrical impulses entered the complex wiring of each of the rotors of the machine, the message was enciphered and then transmitted to the right-hand typewriter. When the enciphered text reached its destination, an operator set the keys of a similar apparatus according to an advisory contained in the message, typed the enciphered signal out on the left-hand machine, and the right hand machine duly delivered the plain text. Until the arrival of the machine cipher system, enciphering was done slowly and carefully by human hand. Now Enigma, as Knox and Turing discovered, could produce an almost infinite number of different cipher alphabets merely by changing the keying procedure. It was, or so it seemed, the ultimate secret writing machine." (14) Mavis Batey, who worked at the Government Code and Cypher School, pointed out the "Polish replica moved the breaking of Enigma on from a theoretical exercise to a practical one and Knox always gave the Poles credit for the part they played." (15)

The Polish replica was taken to the Government Code and Cypher School. On 25th July, 1939, Polish cryptologists held a meeting with French and British intelligence representatives in a meeting at Pyry, south of Warsaw. Britain was represented by Alastair Denniston and Alfred Dilwyn Knox. According to one source, at first the Poles were reluctant to help the British because of their agreement with Adolf Hitler at Munich. (16) Eventually they importantly provided the information that Engima was breakable. Five weeks later the German Army invaded Poland. Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, the author of Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004), that without this information the substantial breaks into German Army and Air Force Enigma ciphers by the British would have occurred several years later. (17)

Knox telephoned the information through to Peter Twinn. By the time Knox returned to GCCS, Twinn had worked out the wheel wiring from this information alone, and had set to work on a few messages sent and interpreted the year before. "I was the first British cryptographer to have read a German services Enigma message. I hasten to say that this did me little if any credit, since with the information Dilly had brought back from Poland, the job was little more than a routine operation." (18)

Bletchley Park

However, it was only with the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 that the British government released the necessary funds to give the expert codebreakers a chance of understanding the messages being sent by the Enigma machine. A special unit was established at Bletchley Park. This was selected because it was more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University and the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (19)

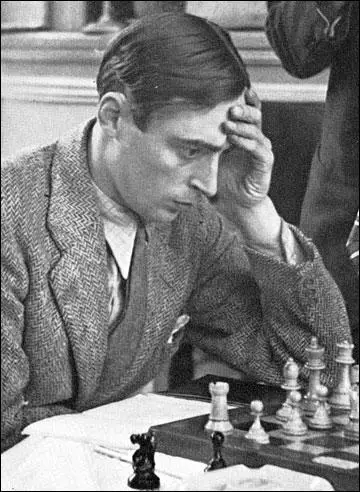

Hugh Alexander, the champion chess player, was invited to join the codebreakers. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Alexander was installed with Stuart Milner-Barry at the Shoulder of Mutton Inn, in Bletchley. Milner-Barry later recalled: "Hugh and I were most comfortably looked after by an amiable landlady, Mrs Bowden. As an innkeeper, she did not seem to be unduly burdened by rationing, and we were able (among other privileges) to invite selected colleagues to supper on Sunday nights, which was a great boon." (20)

Frank Birch and Gordon Welchman were billeted in the Duncombe Arms at Great Brickhill. Another member of staff, Barbara Abernethy, later recalled that Birch was a popular figure at Bletchley Park: "He (Birch) was a great person. I knitted him a blue balaclava helmet which he wore throughout the war. He was billeted in the Duncombe Arms at Great Brickhill. They had a lot of dons there, Gordon Welchman, Patrick Wilkinson. It was full of dons all the time. All of them having such a jolly time that they called it the Drunken Arns." (21)

Gordon Welchman was also involved in recruiting students from university. One of his recruits was Joan Clarke, who had just obtained a double first in Mathematics in Newnham College. (22) Welchman later recalled: "Recruitment of young women went on even more rapidly than that of men. We needed more of them to staff the Registration Room, the Sheet-Stacking Room, and the Decoding Room. As with the men, I believe that the early recruiting was largely on a personal-acquaintance basis, but with the whole of Bletchley Park looking for qualified women, we got a great many recruits of high calibre." (23)

Alan Turing

In December, 1939, Alfred Dilwyn Knox sent a report on the progress that Alan Turing, Peter Twinn, Gordon Welchman and Alan Turing were making to Alastair Denniston. "Welchman is doing well and is very keen... Twinn is still very keen and not afraid of work... Turing is a very difficult to anchor down. He is very clever but quite irresponsible and throws out a mass of suggestions of all degrees of merit. I have just, but only just, enough authority and ability to keep him and his ideas in some sort of order and discipline. But he is very nice about it all." (24)

Turing had difficulty working in a team. Hugh Sebag-Montefiore has suggested he was suffering from Asperger Syndrome: "One of his closest associates suggested that if examined today, he might have been diagnosed to be suffering from a mild form of autism. Perhaps it was Asperger Syndrome, otherwise known as high grade autism, which Isaac Newton is also thought to have had. People with this disorder frequently come up with brilliant ideas which no normal person could have thought of. At the same time, they have no idea how to relate to other people, and cannot understand what other people will think of their behaviour. Asperger Syndrome sufferers are often obsessive about their work, and like to do it alone. Whether or not Turing had Asperger Syndrome, he certainly had many of its symptoms. He was an isolated loner at work and at play." (25)

A fellow codebreaker, Peter Hilton commented: "Alan Turing was unique. What you realise when you get to know a genius well is that there is all the difference between a very intelligent person and genius. With very intelligent people, you talk to them, they come out with an idea, and you say to yourself, if not to them, I could have had that idea. You never had that feeling with Turing at all. He constantly surprised you with the originality of his thinking. It was marvellous." (26)

Frank Birch, the head German subsection of the naval section, based in Hut 4. Birch clashed with both Turing and Peter Twinn. Birch's biographer, Ralph Erskine admits that "although he was not a born leader, and at times had a heavy-handed managerial style, which was an unwise approach to GCCS's free spirits, he cared deeply about his staff and was highly popular with the junior members of his section in consequence". (27) Birch complained in August 1940: "Turing and Twinn are brilliant, but like many brilliant people, they are not practical. They are untidy, they lose things, they can't copy out right, and they dither between theory and cribbing. Nor have they the determination of practical men." Birch was concerned that Turing and Twinn were not making the most of the suggested cribs he and his team were passing on to them. He even suggested that if Turing and Twinn had used this material correctly we "might have won the war by now". Birch went on to argue: "Turing and Twinn are like people waiting for a miracle, without believing in miracles." (28)

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, the author of Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) has pointed out: "Turing was certainly unlike anybody the Foreign Office civil servants had ever worked with before. For a start, he was a practising homosexual which made him a security risk. If he was ever caught breaking the law, he was liable to be blackmailed. Whether or not Denniston knew his sexual preferences, some of his colleagues did. Peter Twinn, Turing's assistant, found out one night in London. Returning to their shared hotel room after dinner, Turing asked Twinn whether they should go to bed together. When Twinn said he was not like that, Turing matter of factly made his excuses and got into his own bed alone." (29)

By studying old decrypted messages, Turing discovered that many of them conformed to a rigid structure. He found that he could sometimes predict part of the contents of an undecyphered message, based on when it was sent and its source. As Simon Singh has explained: "For example, experience showed that the Germans sent a regular enciphered weather report shortly after 6 a.m. each day. So, an encrypted message intercepted at 6.05 a.m. would be almost certain to contain wetter, the German word for 'weather'. The rigorous protocol used by any military organization meant that such messages were highly regimented in style, so Turing could even be confident about the location of wetter within the encrypted message. For example, experience might tell him that the first six letters of a particular cypher text corresponded to the plaintext letters wetter. When a piece of plaintext can be associated with a piece of cypher text, this combination is known as a crib. Turing was sure that he could exploit the cribs to crack Enigma." (30)

The problem for Alan Turing and the rest of the team was that at the time they had to use a "trial and error" approach. This was a very difficult task as there were 159,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible settings to check. R. V. Jones was one of those who worked with Alan Turing on this project: "Together we worked out ways in which the process might be done mechanically, with a machine that would recognize when genuine German was coming out by the frequencies with which various letters and diphthongs appeared." (31)

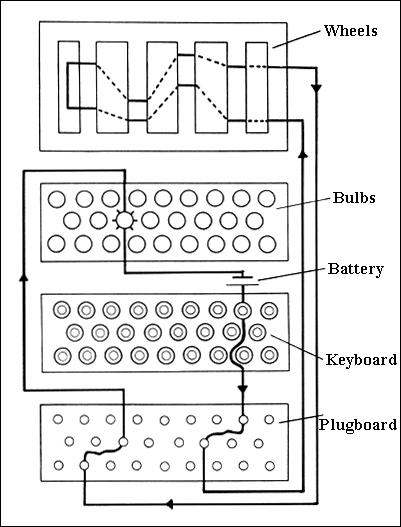

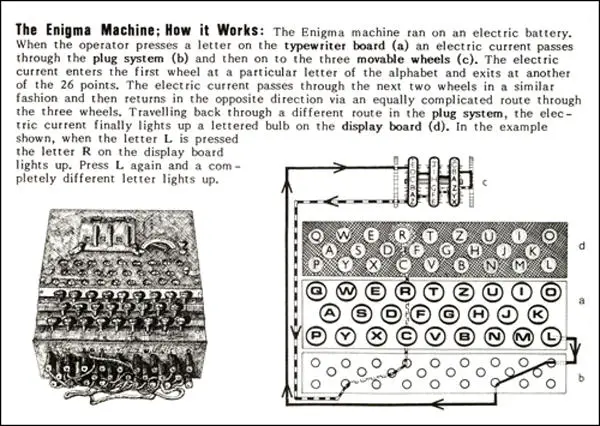

Another member of the team at Bletchley Park, Peter Calvocoressi, explained the task that faced the codebreakers. Although its keyboard was simpler than a typewriter's, the Enigma machine was in all other respects much more complicated. Behind the keyboard the alphabet was repeated in another three rows and in the same order, but this time the letters were not on keys but in small round glass discs which were set in a flat rectangular plate and could light up one at a time. When the operator struck a key one of these letters lit up. But it was never the same letter. By striking P the operator might, for example, cause L to appear; and next time he struck P he would get neither P nor L but something entirely different. This operator called out the letters as they appeared in lights and a second operator sitting alongside him noted them down. This sequence was then transmitted by wireless in the usual Morse code and was picked up by whoever was supposed to be listening for it."

Both the person sending and receiving the message had a handbook that told him what he had to do each day. This included the settings of the machine. As Calvocoressi pointed out: "These parts or gadgets consisted of a set of wheels rotors and a set of plugs. Their purpose was not simply to turn P into L but to do so in so complex a manner that it was virtually impossible for an eavesdropper to find out what had gone on inside the machine in each case. It is quite easy to construct a machine that will always turn P into L, but it is then comparatively easy to find out that L always means P; a simple substitution of this kind is inadequate for specially secret traffic. The eavesdropper's basic task was to set his machine in exactly the same way as the legitimate recipient of the message had set his, since the eavesdropper would then be able to read the message with no more difficulty than the legitimate recipient. The more complex the machine and its internal workings, the more difficult and more time-consuming was it for the eavesdropper to solve this problem.... Although only three wheels could be inserted into the machine at any one time, there were by 1939 five wheels issued with each machine. The operator had to use three of this set of five. He had to select the correct three and then place them in a prescribed order. This was crucial because the wheels, although outwardly identical, were differently wired inside." (32)

Turing's Machine

Alan Turing had a meeting with Marian Rejewski, a mathematician who had been working for the Polish Cypher Bureau, before he joined the Government Code and Cypher School. He had been trying for seven years to understand the workings of the Enigma machine. When the country was invaded by the German Army, Rejewski managed to escape to France. He told Turing that he had come to the conclusion that as the code had been generated by a machine it could be broken by a machine. In Poland he had built a machine that he named "bomba kryptologiczna" or "cryptological bomb". This machine took over 24 hours to translate a German message on an Enigma machine. Turing was impressed by what Rejewski had achieved but realised that they must find a way of achieving this in a shorter time period if this breakthrough was to be effective. (33)

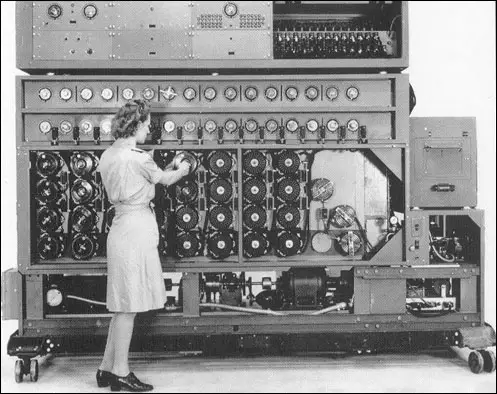

Alan Turing set about developing an engine that would increase the speed of the checking process. Turing finalized the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bombe") was in a copper-coloured cabinet. (34) "The result was a huge machine six-and-a-half feet tall, seven feet long and two feet wide. It weighed over a ton, with thirty-six 'scramblers' each emulating an Enigma machine and 108 drums selecting the possible key settings." (35) Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (36)

To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (37) The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. It was some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. (38) "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (39) They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (40)

Frederick Winterbotham was the chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (41)

A more improved version, called Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), was delivered on 8th August. From this point onwards, Bletchley Park was able to read, on a daily basis, every single Luftwaffe message - something in the region of one thousand a day. (42) At the time, the Battle of Britain was raging and the German codes were being broken at Bletchley Park, allowing the British to direct their fighters against incoming German bombers. When the battle was won the codebreakers intercepted messages cancelling the planned invasion of Britain - Operation Sealion. (43)

Hugh Alexander was based in Hut 8 (Naval Enigma) as deputy head under Alan Turing. According to his biographer, Ralph Erskine: "Documents captured in the spring led to breakthroughs which enabled Hut 8 to solve the main Kriegsmarine cipher, codenamed Dolphin by GCCS, from August onwards. Alexander was outstanding at a Bayesian probability system invented by Turing, called Banburismus, which he considerably improved. Banburismus made the production of operationally useful decodes possible by greatly reducing the number of tests on the ‘bombes’ (high-speed key-finding aids), which were in very short supply." (44)

However, Alexander was keen to point out: "There should be no question in anyone's mind that Turing's work was the biggest factor in Hut 8's success. In the early days, he was the only cryptographer who thought the problem worth tackling and not only was he primarily responsible for the main theoretical work within the Hut (particularly the developing of a satisfactory scoring technique for dealing with Banburismus) but he also shared with Welchman and Keen the chief credit for the invention of the Bombe... the pioneer work always tends to be forgotten when experience and routine later make everything seem easy and many of us in Hut 8 felt that the magnitude of Turing's contribution was never fully realised by the outside world." (45)

Hugh Alexander argued that Alan Turing had problems with his superiors over funding: "He (Alan Turing) was always impatient of pompousness or officialdom of any kind indeed it was incomprehensible to him; authority to him was based solely on reason and the only grounds for being in charge was that you had a better grasp of the subject involved than anyone else. He found unreasonableness in others very hard to cope with because he found it very hard to believe that other people weren't all prepared to listen to reason; thus a practical weakness in him in the office was that he wouldn't suffer fools or humbugs as gladly as one sometimes has to." (46)

John Cairncross was a fluent German speaker, and was posted to the Government Code and Cypher School and assigned to work in Hut 3. (39) Cairncross later recalled in his autobiography: "The linguists were more typical of an Oxbridge educational background and were later recruited in greater numbers in order to process the fruit of the progress made by the technicians. As fluency in German was a very scarce commodity in England, I was automatically assigned to ENIGMA when I was called up... After a short training in simple (non-machine) codes at nearby Bedford, which never proved useful, I was sent to Bletchley and put to work. We lived a semi-monastic life, which was only broken by the occasional visit to London to recuperate.... Weekends were unheard of since the operational work was non-stop. Social functions too were virtually ruled out by working conditions and there were no common rooms. The rigid separation of the different units made contact with other staff members almost impossible, so I never got to know anyone apart from my direct operational colleagues. We did eight fully-occupied hours of work and then were transported back to our respective lodgings with families in the surrounding villages." (47)

The Hut System

The Victorian mansion of Bletchley Park was used as the administrative office of the Government Code and Cypher School. The head of the GCCS was located on the ground floor that "looked out across a wide lawn to a pond, with attractively landscaped banks". (48) At first, the codebreakers, under the control of Alfred Dilwyn Knox, were allocated working space in "a row of chunky converted interlinked houses - just across the courtyard from the main house, near the stables". It became known as the "Cottage". (49) Knox's department consisted of ten people, including "two very brilliant" young women, Margaret Rock and Mavis Batey. (50) Mavis later recalled. "We were all thrown in the deep end. No one knew how the blessed thing worked. When I first arrived, I was told, 'We are breaking machines, have you got a pencil? And that was it. You got no explanation. I never saw an Enigma machine. Dilly Knox was able to reduce it - I won't say to a game, but a sort of linguistic puzzle. It was rather like driving a car while having no idea what goes on under the bonnet." (51) "We were looking at new traffic all the time or where the wheels or the wiring had been changed, or at other new techniques. So you had to work it all out yourself from scratch.” (52)

Inside the grounds of Bletchley Park they built several prefabricated wooden huts. In the intitial stages of the war the huts served different purposes: Hut 1 (Wireless Station and from March 1940, the home of the first Bombe, "Victory"); Hut 2 (recreational area that provided tea and beer); Hut 3 (translation and analysis of Army and Air Force decrypts); Hut 4 (Naval Intelligence); Hut 5 (military intelligence including Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese ciphers and German police codes) Hut 6 (cryptanalysis of Army and Air Force Enigma); Hut 7 (cryptanalysis of Japanese naval codes and intelligence) and Hut 8 (cryptanalysis of Naval Enigma). Later other huts were built to house decryption machines. These huts were like small factories. In September 1943, when Stuart Milner-Barry was promoted head of Hut 6, it comprised about 450 staff.

Francis Harry Hinsley was originally sent to Hut 3: "Hut 3 was set up like a miniature factory. At its centre was the Watch Room - in the middle a circular or horseshoe-shaped table, to one side a rectangular table. On the outer rim of the circular table sat the Watch, some half-dozen people. The man in charge, the head of the Watch or Number 1, sat in an obvious directing position at the top of the table. The watchkeepers were a mixture of civilians and serving officers, Army and RAF. At the rectangular table sat serving officers, Army and RAF, one or two of each. These were the Advisers. Behind the head of the Watch was a door communicating with a small room where the Duty Officer sat. Elsewhere in the Hut were one large room housing the Index and a number of small rooms for the various supporting parties, the back rooms. The processes to which the decrypts were submitted were, consecutively, emendation, translation, evaluation, commenting, and signal drafting. The first two were the responsibility of the Watch, the remainder of the appropriate Adviser." (53)

Oliver Lawn worked in Hut 6: "I was concerned with the codebreaking and that was it. When the code had been broken, the decoded message was passed through to the Intelligence people who used the information - or decided whether to use it. The content of messages was of no concern to me at all. I knew enough German to get an idea of what it was all about. But I had no idea of the context. And it wasn't my business. I could read the messages but they were so much in telegraphese, jargon, that they would mean nothing." (54)

Peter Twinn pointed out that it was very much a team effort: "When the codebreakers had broken the code they wouldn't sit down themselves and painstakingly decode 500 messages. I've never myself personally decoded a message from start to finish. By the time you've done the first twenty letters and it was obviously speaking perfectly sensible German, for people like me that was the end of our interest." The message was now passed on people such as Diana Russell Clarke: "The cryptographers would work out the actual settings for the machines for the day. We had these Type-X machines, like typewriters but much bigger. They had three wheels, I think on the left-hand side, all of which had different positions on them. When they got the setting, we were to set them up on our machines. We would have a piece of paper in front of us with what had come over the wireless. We would type it into the machine and hopefully what we typed would come out in German." (55)

Employment of Women at GCCS

Keith Batey later recalled that Alastair Denniston liked appointing young women from upper-class families: "The first two girls (employed at GCCS) were the daughters of two chaps that Denniston played golf with at Ashtead. Denniston knew the family, he knew that they were nice people and... well, that their daughters wouldn't go around opening their mouths and saying what was going on. The background was so important if they were the sort of people who were not going to go around telling everyone what they were doing." (56)

Sarah Baring was the daughter of the Richard Henry Brinsley Norton, 6th Lord Grantley. At the beginning of the war Sarah and her friend, Osla Benning, went to work at the Hawker-Siddeley aircraft factory in Slough. (57) "When the war started, me and a great friend of mine, Osla Benning (Henniker-Major), decided we wanted to do something really important. And we thought: making aeroplanes.... We had to learn how to cut Durol, which the planes were made of. We did that for a while, and then Osla and I felt we weren't really doing enough." (58)

In 1941 Sarah and Osla, received a letter from the Foreign Office stating: "You are to report to Station X at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, in four days time." (59) Sarah later recalled: "Then suddenly, through the post, came a letter, God knows who from, asking us to report to the head of Bletchley - forthwith. That was all. So we thought: Anything's better than making aeroplanes at the moment." It seems that Lord Louis Mountbatten, her godfather, had put her name forward.

Denniston was persuaded by people like Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Gordon Welchman to employ women who had already distinguished themselves as mathematicians. Welchman, a mathematician from Sidney Sussex College, brought in Joan Clarke, who had graduated in 1939 from Newnham College with a double first in Mathematics. She worked with Alan Turing and eventually became Deputy Head of Hut 8. (60)

Knox, the senior cryptographer at Bletchley Park, and the man who has been described as "the mastermind" behind breaking the Enigma code, had a reputation for employing women. His unit was based in what was called the "Cottage" (in reality, a row of chunky converted interlinked houses - just across the courtyard from the main house, near the stables). (61)

Knox admitted that he liked employing women. According to Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010): "Dilwyn Knox... found that women had a greater aptitude for the work required - as well as nimbleness of mind and capacity for lateral thought, they possessed a care and attention to detail that many men might not have had." Two of the women in his unit, Mavis Batey and Margaret Rock, became important codebreakers. Mavis later recalled: "A myth has grown up that Dilly (Knox) went around in 1939 looking at the girls arriving at Bletchley and picking the most attractive for the Cottage.... That is completely untrue. Dilly took us on our qualifications." (62)

Knox was so impressed with the work of Mavis and Margaret that in August 1940, he contacted head office in an effort to get them a pay rise: "Miss Lever (later Mavis Batey) is the most capable and the most useful and if there is any scheme of selection for a small advancement in wages, her name should be considered.... Miss M. Rock is entirely in the wrong grade. She is actually 4th or 5th best of the whole Enigma staff and quite as useful as some of the 'professors'. I recommend that she should be put on to the highest possible salary for anyone of her seniority." (63)

Mavis Batey and Margaret Rock worked with Knox on the "updated Italian Naval Enigma machine, checking all new traffic and even the wheels, cogs and wiring to see how it was constructed." (64) In March 1941 Mavis deciphered a message, “Today 25 March is X-3". She later recalled that "if you get a message saying 'today minus three', then you know that something pretty big is afoot." Working with a team of intelligence analysts she was able to work out that the Italian fleet was planning to attack British troop convoys sailing from Alexandria to Piraeus in Greece. As a result of this information the British Navy was able to ambush four Italian destroyers and four cruisers off the coast of Sicily. Over 3,000 Italian sailors died during the Battle of Cape Matapan. Admiral John Henry Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence, sent a message to Bletchley Park: "Tell Dilly (Knox) that we have won a great victory in the Mediterranean and it is entirely due to him and his girls." (65)

Mavis and Margaret also played a very important role in breaking of the Enigma cipher used by the German secret service, the Abwehr. This was a vital aspect of what became known as the Double-Cross System (XX-Committee). Created by John Masterman, it was an operation that attempted to turn "German agents against their masters and persuaded them to cooperate in sending false information back to Berlin." (66) Masterman needed to know if the Germans believed the false intelligence they were receiving.

As the The Daily Telegraph later explained: "On December 8 1941 Mavis Batey broke a message on the link between Belgrade and Berlin, allowing the reconstruction of one of the rotors. Within days Knox and his team had broken into the Abwehr Enigma, and shortly afterwards Mavis broke a second Abwehr machine, the GGG, adding to the British ability to read the high-level Abwehr messages and confirm that the Germans did believe the phony Double-Cross intelligence they were being fed by the double agents." (67)

This was not the last of these women's breakthroughs. In February 1942, Mavis Batey solved the Enigma used by the Abwehr solely for communications between Madrid and several outstations situated around the Strait of Gibralter. Margaret Rock has been given credit for solving the Enigma being used by the Germans between Berlin and the Canaries in May 1943. (68)

Funding of GCCS

Commander Edward W. Travis replaced Alastair Denniston as head of GCCS in February, 1941. (69) Later that year, Hugh Alexander, Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Stuart Milner-Barry wrote a letter to Winston Churchill concerning the funding of GCCS: "Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention."

The men added: "We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken." (70)

Churchill told his principal staff officer, General Hastings Ismay: "Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done." (71) By the end of 1942 there were 49 Turing machines. As part of the recruitment drive, the Government Code and Cypher School placed a letter in the Daily Telegraph. They issued an anonymous challenge to its readers, asking if anybody could solve the newspaper's crossword in under 12 minutes. It was felt that crossword experts might also be good codebreakers. The 25 readers who replied were invited to the newspaper office to sit a crossword test. The six people who finished the crossword first were interviewed by military intelligence and recruited as codebreakers at Bletchley Park. (72)

Operation of Deciphering Machines

Oliver Lawn pointed out: "After the first two, a large number of machines were made to a fairly standard form. It proved its use. Altogether about two hundred were made. The first ones were located at Bletchley itself, in what is now called the Bombe Room (Hut 11), which still exists. But when the numbers grew bigger, they had to use other places, and as the war went on, most of them were put at two locations in north London - Eastcote and Stanmore. They had roughly a hundred machines each, run by a large company of Wrens in both cases." (73)

By 1943 there were nearly 200 of these machines at Bletchley Park and its various out-stations. (74) These machines were run by the Women's Royal Naval Service. One of the women working on these deciphering machines, Cynthia Waterhouse, described how they worked: "The intricate deciphering machines were known as bombes. These unravelled the wheel settings for the Enigma ciphers thought by the Germans to be unbreakable. They were cabinets about eight feet tall and seven feet wide. The front housed rows of coloured circular drums each about five inches in diameter and three inches deep. Inside each was a mass of wire brushes, every one of which had to be meticulously adjusted with tweezers to ensure that the circuits did not short. The letters of the alphabet were painted round the outside of each drum. The back of the machine almost defies description - a mass of dangling plugs on rows of letters and numbers." (75)

Jean Valentine was just over five foot and according to Bletchley guidelines, too short and had to use a special stool to reach the highest drums: "When you're younger, your fingers are very flexible, you can do things much more quickly. And the brain works quicker.... I don't like noise. But to me, it was like a lot of knitting machines working - a kind of ticketery clickety noise. It was repetitive but I can't say I found it upsettingly noisy." (76) She explained the women came from a wide-range of different occupations. "You did meet people from both above and below you, as it were, and it was OK. One girl had been evacuated to America at the start of the war, but when she reached eighteen, she came back in order to join up. There were others who were clearly a little more working-class." (77)

Cynthia Waterhouse explained: "We were given a menu which was a complicated drawing of numbers and letters from which we plugged up the back of the machine and set the drums on the front.... We only knew the subject of the key and never the contents of the messages. It was quite heavy work and now we understood why we were all of good height and eyesight, as the work had to be done at top speed and 100% accuracy was essential. The bombes made a considerable noise as the drums revolved, and would suddenly stop, and a reading was taken. If the letters matched the menus, the Enigma wheel-setting had been found for that particular key. To make it more difficult the Germans changed the setting every day. The reading was phoned through to the Controller at Bletchley Park where the complete messages were deciphered and translated." (78)

The encrypted message was typed out in German: "Everything was so brilliantly compartmentalised... I worked in the bombe room. And when we got an answer from the machines, we went to the phone, to ring through this possible answer to an extension number. It wasn't until all these decades later that I realised we were just calling Hut 6 across the path... Then they (the encrypted message) went to the pink hut which was just opposite to the entrance of Hut 11, not six steps away. There the translators changed it into English. And the analysts decided who was going to get this information. This was all happening in this tiny little square. I saw nothing of Bletchley Park except that grass oval in front of the mansion." (79)

Primary Sources

(1) Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars (c. AD 110)

There are also letters of his to Cicero, as well as to his intimates on private affairs, and in the latter, if he had anything confidential to say, he wrote it in cipher, that is, by so changing the order of the letters of the alphabet, that not a word could be made out. If anyone wishes to decipher these, and get at their meaning, he must substitute the

fourth letter of the alphabet, namely D, for A, and so with the others.

(2) Michael Paterson, Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

When its owner died in 1937 Bletchley Park, set in the Buckinghamshire countryside about 50 miles north-west of London, was an unremarkable Victorian country house. Situated at the end of a drive and surrounded by lawns that sloped gently to an ornamental lake, it had been largely rebuilt after 1883 when it had been bought by the financier Sir Herbert Leon. Its red-brick faqade boasted neither symmetry nor beauty: it was an eclectic assemblage of gables, crenellations, chimney-stacks and bay windows - perhaps a suitably eccentric setting for the role it was destined soon to play. Tucked behind it were the usual outbuildings: stables, garages, laundry and dairy facilities, and servants' living quarters. Of no historic or architectural importance, it was bought by a local builder for demolition and redevelopment.

Within a year, however, the house had changed hands again. Its new occupant appeared to be a naval or military gentleman, and he was accompanied by a group described as "Captain Ridley's shooting party". This term suggested a group of sporting upper-class men in pursuit of local wildlife, yet no gunshots were heard from the grounds. Instead, in the years that followed there would be the sounds of almost constant construction. The mysterious gentleman were to remain in occupation for almost ten years, their numbers swelled by over 10,000 more men and women, both military and civilian, and it would be several more decades before local people discovered what they had been doing there.

(3) Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra (1980)

The original version of the Enigma machine was invented and patented in 1919 in Holland and was developed and marketed in the early twenties by a German who incorporated the Dutch invention with his own and gave the machine its name. It was a commercial machine which anybody could buy. Patents were taken out in various countries including Britain and these were open to inspection by anybody who knew where to look for them and had the curiosity to do so.

Among the purchasers of this commercial machine were the German armed services. The German navy had been thinking of finding and adapting a machine for its cyphers as early as 1918, and in 1926 it began to use an improved version of Enigma. The army followed suit three years later; there was as yet no air force, but eventually the Luftwaffe used Enigma too and so did the German security services (the police and SS) and other services like the railways. Over the years the Germans progressively altered and complicated the machine and kept everything about it more and more secret. The basic alterations from the commercial to the secret military model were completed by 1930/31 but further operating procedures continued to be introduced before and during the war. The Enigma machine was to be far and away the most important tool for the Germans' strategic battlefield communications during the Second World War, although it could have been superseded if the war had gone on much longer than it did.

(4) Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies (1976)

Lewinski worked in an apartment on the Left Bank, and the machine he created was a joy of imitative engineering. It was about 24 inches square and 18 inches high, and was enclosed in a wooden box. It was connected to two electric typewriters, and to transform a plain-language signal into a cipher text, all the operator had to do was consult the book of keys, select the key for the time of the day, the day of the month, and the month of the quarter, plug in accordingly, and type the signal out on the left-hand typewriter. Electrical impulses entered the complex wiring of each of the rotors of the machine, the message was enciphered and then transmitted to the right-hand typewriter. When the enciphered text reached its destination, an operator set the keys of a similar apparatus according to an advisory contained in the message, typed the enciphered signal out on the left-hand machine, and the right hand machine duly delivered the plain text. Until the arrival of the machine cipher system, enciphering was done slowly and carefully by human hand. Now Enigma, as Knox and Turing discovered, could produce an almost infinite number of different cipher alphabets merely by changing the keying procedure. It was, or so it seemed, the ultimate secret writing machine."

(5) R. V. Jones, Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945 (1978)

This was a very ingenious arrangement of three wheels, each one of which had a sequence of studs on each side, with each stud on one side being connected by a wire to a pin on the other side - the exact arrangement of the connections being one of the secrets of the machine and the pin making contact with one of the studs on the next wheel. The machine had a typewriter keyboard, and it was worked rather like a cyclometer: every time the machine was operated to encode a letter, one wheel would be turned by one space; after this wheel had moved by enough spaces to turn it through one revolution, it would click its neighbouring wheel by one space. The wheels were thus never in the same position twice. The basic encoding was effected by the passage of an electric current through the studs so that when a letter was to be encoded, the appropriate key would be pressed on the keyboard, and the resultant coded letter would be determined by the appropriate conducting path through the studs, the studs on one wheel making suitable contact with the pins on the neighbouring wheel. A further touch of ingenuity was to add a reversing arrangement at the edge of the third wheel, again with studs cross-connected so as to send the current backwards through the wheels by yet another path. The returning current lit a small electric bulb which illuminated a particular letter on a second keyboard, and thus indicated the enciphered equivalent of the letter whose key had originally been pressed."

(6) Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra (1980)

Although its keyboard was simpler than a typewriter's, the Enigma machine was in all other respects much more complicated. Behind the keyboard the alphabet was repeated in another three rows and in the same order, but this time the letters were not on keys but in small round glass discs which were set in a flat rectangular plate and could light up one at a time. When the operator struck a key one of these letters lit up. But it was never the same letter. By striking P the operator might, for example, cause L to appear; and next time he struck P he would get neither P nor L but something entirely different.

This operator called out the letters as they appeared in lights and a second operator sitting alongside him noted them down. This sequence was then transmitted by wireless in the usual Morse code and was picked up by whoever was supposed to be listening for it. It could also be picked up by an eavesdropper. The Germans experimented with a version of the machine which, by transmitting automatically as the message was encyphered, did away with the need for the second operator, but they never brought this version into use.

The legitimate recipient took the gobbledegook which had been transmitted to him and tapped it out on his machine. Provided he got the drill right the message turned itself back into German. The drill consisted in putting the parts of his machine in the same order as those of the sender's machine. This was no problem for him since he had a handbook or manual which told him what he had to do each day. In addition, the message which he had just received contained within itself the special key to that message.

The eavesdropper on the other hand had to work all this out for himself. Even assuming he had an Enigma machine in full working order it was no good to him unless he could discover how to arrange its parts - the gadgets which it had in addition to its keyboard. These were the mechanisms which caused L to appear when the operator struck P.

These parts or gadgets consisted of a set of wheels rotors and a set of plugs. Their purpose was not simply to turn P into L but to do so in so complex a manner that it was virtually impossible for an eavesdropper to find out what had gone on inside the machine in each case. It is quite easy to construct a machine that will always turn P into L, but it is then comparatively easy to find out that L always means P; a simple substitution of this kind is inadequate for specially secret traffic.

The eavesdropper's basic task was to set his machine in exactly the same way as the legitimate recipient of the message had set his, since the eavesdropper would then be able to read the message with no more difficulty than the legitimate recipient. The more complex the machine and its internal workings, the more difficult and more time-consuming was it for the eavesdropper to solve this problem.

The Enigma machine fitted compactly into a wooden box which measured about 13 x 11 inches, and 6 inches high.

As the operator sat at his machine, he had in front of him, first, the rows of keys, then the spaces for the letters to appear illuminated, and beyond these again a covered recess to take three wheels or rotors. Each wheel was about three inches in diameter and had 26 points of entry and exit for the electric current which passed through them. The wheels were almost wholly embedded in the machine and edge-on to the operator. They were covered by a lid and when the lid was closed the operator could see only the tops of them, but he could rotate them by hand because each wheel had on one side a serrated edge which stuck up through the lid.In addition to this serrated edge each wheel had, on its other side, a ring which could be moved independently of the wheel itself into any one of 26 positions round the wheel. Thus the wheel could be manipulated and so could the ring. Further, each wheel rotated automatically when the machine was in use - the right hand wheel at each touch of a key, the middle wheel after 26 touches, and the left hand wheel after 26 x 26.

Although only three wheels could be inserted into the machine at any one time, there were by 1939 five wheels issued with each machine. The operator had to use three of this set of five. He had to select the correct three and then place them in a prescribed order. This was crucial because the wheels, although outwardly identical, were differently wired inside.

(7) Rules of Bletchley Park (September, 1939)

No mention whatsoever may be made either in conversation or correspondence regarding the nature of your work. It is expressly forbidden to bring cameras etc. within the precincts of Bletchley Park (Official Secrets Act).

DO NOT TALK AT MEALS. There are the waitresses and others who may not be in the know regarding your own particular work.

DO NOT TALK TO THE TRANSPORT. There are the drivers who should not be in the know.

DO NOT TALK TRAVELLING. Indiscretions have been overheard on Bletchley platform. They do not grow less serious further off.

DO NOT TALK IN THE BILLET. Why expect your hosts who are not pledged to secrecy to be more discreet than you, who are?

DO NOT TALK BY YOUR OWN FIRESIDE, whether here or on leave. If you are indiscreet and tell your own folks, they may see no reason why they should not do likewise. They are not in a position to know the consequences and have received no guidance. Moreover, if one day invasion came, as it perfectly well may, Nazi brutality might stop at nothing to wring from those that you care for, secrets that you would give anything, then, to have saved them from knowing. Their only safety will lie in utter ignorance of your work.

BE CAREFUL EVEN IN YOUR HUT. Cleaners and maintenance staff have ears, and are human.

(8) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014)

The first bombe, named Victory, arrived at Bletchley Park on 18 March 1940. It cost £6,500, one-tenth of the price of a Lancaster bomber and around £100,000 today. It was also some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. But already Turing was working on plans to make a machine that was faster still.

(9) Cynthia Waterhouse, interviewed by Michael Paterson, for his book, Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

The intricate deciphering machines were known as bombes. These unravelled the wheel settings for the Enigma ciphers thought by the Germans to be unbreakable. They were cabinets about eight feet tall and seven feet wide. The front housed rows of coloured circular drums each about five inches in diameter and three inches deep. Inside each was a mass of wire brushes, every one of which had to be meticulously adjusted with tweezers to ensure that the circuits did not short. The letters of the alphabet were painted round the outside of each drum. The back of the machine almost defies description - a mass of dangling plugs on rows of letters and numbers.

We were given a menu which was a complicated drawing of numbers and letters from which we plugged up the back of the machine and set the drums on the front. The menus had a variety of cover names - e.g. silver drums were used for shark and porpoise menus for naval traffic, and phoenix, an army key associated with tank battles at the time of El Alamein.

We only knew the subject of the key and never the contents of the messages. It was quite heavy work and now we understood why we were all of good height and eyesight, as the work had to be done at top speed and 100% accuracy was essential. The bombes made a considerable noise as the drums revolved, and would suddenly stop, and a reading was taken. If the letters matched the menus, the Enigma wheel-setting had been found for that particular key. To make it more difficult the Germans changed the setting every day. The reading was phoned through to the Controller at Bletchley Park where the complete messages were deciphered and translated. The good news would be a call back to say "Job up, strip machine."

(8) John Cairncross, The Enigma Spy (1996)

I was posted to the secret and vital operation of deciphering signals of foreign military forces carried out at the Government Code & Cipher School (GC&CS), which had moved shortly before the war from the SIS headquarters in London to the small town of Bletchley, some sixty miles on the main railway line to the north, where it was safely hidden from German bombers. The school itself would not have aroused suspicion, set in the grounds of a hideous nineteenth-century Victorian mansion, which would serve as its administrative headquarters. But if one looked through the high steel fence which guarded the compound from intruders, one could see a cluster of dingy prefabricated huts of the type normally found in army camps. It was in these unimpressive structures that the most important technical breakthrough of the Second World War took place: the cracking of the ENIGMA cipher machine, a model of which had been provided to the British by a courageous group of Polish cryptographers who had been working for the Germans. Yet the final breakthrough was due to the skill and tenacity of British experts.

The staff at Bletchley Park, but mainly its cryptographers and other technicians, was a mixed group, chaotically assembled during the early years of the war. They were not the typical product of the older universities, where the cult and cultivation of social polish and homogeneity were mostly prized above scientific and commercial ingenuity. Churchill himself made the point with his usual pungent humour, in a rapid visit to the GC&CS in 1941, when he commented to Commander (Sir) Edward Travis, the Director: "I know I told you to leave no stone unturned to find the necessary staff, but I didn't mean you to take me literally." But these were the experts who produced solutions of genius for the nation's wartime problems by developing an even more ingenious device than the ENIGMA machine itself. This machine, designed by the mathematical genius Alan Turing, was a forerunner of the modern computer and reduced the laborious process of examining the infinite possibilities of interpretation to manageable proportions. The culmination of these efforts was that the unintelligible texts transmitted by the Germans in cipher could be "unscrambled" and restored to their original text. This was not a once and for all battle, but a struggle to meet a constant challenge, since it was possible for the settings of the ENIGMA machine to be endlessly changed by the Germans; but the British technicians rose to the challenge. (We linguists only rarely caught a glimpse of the difficulties encountered by the technical side in the decipherment of the signals, which called for a different sort of mind.)

The linguists were more typical of an Oxbridge educational background and were later recruited in greater numbers in order to process the fruit of the progress made by the technicians. As fluency in German was a very scarce commodity in England, I was automatically assigned to ENIGMA when I was called up. I suppose my position as Private Secretary to Lord Hankey had been a sufficient guarantee of reliability, and I was taken on by the GC&CS and not even subjected to any interrogation.

After a short training in simple (non-machine) codes at nearby Bedford, which never proved useful, I was sent to Bletchley and put to work. We lived a semi-monastic life, which was only broken by the occasional visit to London to recuperate. There was a direct train to London, so that travel back to my flat there on my day off was not a problem. I had no car at the time and indeed not even a driving licence, but GC&CS was within walking distance of the railway station. Weekends were unheard of since the operational work was non-stop. Social functions too were virtually ruled out by working conditions and there were no common rooms. The rigid separation of the different units made contact with other staff members almost impossible, so I never got to know anyone apart from my direct operational colleagues. We did eight fully-occupied hours of work and then were transported back to our respective lodgings with families in the surrounding villages.

Even within my hut, I never met some of the more important personalities, such as Peter Calvocoressi, who wrote a book on his experiences at Bletchley. Except for the work and the routine, I remember very little of what happened there during my twelve months' service. My territory was limited to my hut and to the functional and austere cafeteria, which could hardly be described as having a relaxed and inviting atmosphere.

When I discovered the nature of the work I was to be engaged in, I was proud to take part in this superb achievement of British brains, and was soon fascinated with the job itself. Few of us were military experts or had any knowledge of the details of the fighting, so our satisfaction was with the work itself. I found the editing of the German decrypts much like solving a crossword puzzle, or amending a corrupt text of a classical writer such as Moliere. My work involved the correction and restoration of words blurred, distorted or omitted. This was a task which needed a generous dose of imagination, and a corkscrew mind.

The translators/editors operated in groups of six, including a team leader. The German ENIGMA (ULTRA SECRET) decrypts came in rolls of paper three or four feet long, each roll containing some ten signals. The leader's task was to decide whether the signals were worth processing (as was rarely the case), to check out if translations were accurate, and to make sure that no information was overlooked which had a tactical or organisational significance. For instance, at the beginning of my new career, I overlooked the implications of a particular phrase containing a reference to a German Luftwaffe unit in Yugoslavia, which could have been identified by relating this passage to a previous signal received two days earlier. There was another instance later on in which a passage did not seem to make sense, no matter how hard I racked my brains trying out various solutions. It turned out that two signals had been run together, and that this crucial factor had been overlooked by the expert attached to the cryptographic section.

The team leader had to ascribe a fictitious source for each signal and ensure that it was plausible, for the translation was careful never to give the slightest hint of the real origin of the document. The kind of source ascribed, for example, would be a mythical British agent such as an officer in the German Army High Command (OKW). Our product was known as the "sanitised" version of ULTRA SECRET and was the one supplied to all recipients, including the War Office...

I had been greeted on my first day at Bletchley by the receiving officer who explained to me the billeting system and informed me about other practical matters such as transportation to and from work. He emphasised the utterly secret nature of the decipherment operations and the need for complete secrecy in all our work, since, if the Germans suspected that Britain was reading ENIGMA, they would change the cipher and we would take a long time, if ever, to break into it again. We might even lose the war as a result. He ended the interview with the striking, if casual, announcement that we had not confided our ENIGMA triumph to the Russians "because we do not trust them". They were, he implied, a security risk.

This offhand announcement shook me and set my mind racing. I had arrived at Bletchley with the determination to sever my connection with the KGB. I felt certain that the Government, and Churchill in particular, would not have excluded the Russians from this important source of intelligence without the I had been greeted on my first day at Bletchley by the receiving officer who explained to me the billeting system and informed me about other practical matters such as transportation to and from work. He emphasised the utterly secret nature of the decipherment operations and the need for complete secrecy in all our work, since, if the Germans suspected that Britain was reading ENIGMA, they would change the cipher and we would take a long time, if ever, to break into it again. We might even lose the war as a result. He ended the interview with the striking, if casual, announcement that we had not confided our ENIGMA triumph to the Russians "because we do not trust them". They were, he implied, a security risk.

There were two most probable grounds for the ban. I speculated and feared that even if the Allies won the war, their basic differences would, in the not-too-far-distant future, lead to the parting of ways. Even now relations were far from perfect. I recall Churchill's Private Secretary, John Colville, telling me that his master had once confided in him that there was no limit to the deceptiveness of the Russians. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact may have been thrust aside for the moment, just as the long list of Stalin's horrors was tactfully overlooked, but they could not be extinguished or forgotten. The other consideration was a technical but vital one. The Germans might now or later crack the Russian military cipher, and in that case, since the Russians would be making the most of ENIGMA information in their traffic, the Germans would soon be aware that their own cipher had been read.

(9) Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander, and Stuart Milner-Barry, letter to Winston Churchill (21st October, 1941)

Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention...

We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken.