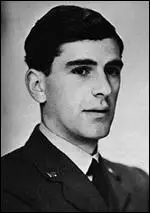

Peter Calvocoressi

Peter Calvocoressi was born in Karachi on 17th November 1912. His family came from the Greek island of Chios but his father was a French citizen who had became a naturalised British subject during the First World War. (1) When he was three months old the family moved to Liverpool. "He grew up with Greek friends, spoke French at home as well as English and had family trips to Italy and Greece." (2)

In 1926 he sat the Eton College scholarship examinations and was placed second. At school he discovered a facility for languages, adding German and Italian to the English and French that he spoke at home. Calvocoressi studied history at Balliol College and after leaving Oxford University in 1934 he attempted to join the diplomatic service but was rejected because his father had been born in France. (3)

Calvocoressi later commented: "The education I received was excellent. Also, although I did not realise this at the time, it gave me a passport. Having emerged from Eton and Balliol I had become, potentially at least, Establishment material. I had also picked up a couple of secondary advantages in academic distinction (a scholarship at Eton and a First at Oxford) and a facility for languages. In the ordinary course of events I might be a somewhat disadvantaged member of the Establishment, endowed with a tongue twisting name and debarred from some kinds of official employment." (4)

Second World War

Calvocoressi became a barrister and in 1938 he married Barbara Eden, the daughter of Michael Eden, the 7th Baron Henley. (5) On the outbreak of the Second World War he was recruited into the Ministry of Economic Warfare which was established in the London School of Economics. "Its job was to find the bottlenecks in the German economy and squeeze them. Some optimists thought that in this way the German war machine could be brought to a halt by Christmas but this euphoria did not survive the test of experience and the Ministry, having been shifted to more commodious quarters in Berkeley Square, settled to a less spectacular but none the less useful role in the war." (6)

In 1940 he "decided I ought to do something more active than impede the neutrals' commerce with Germany" and joined the Royal Air Force. (7) "I resolved to volunteer for the army instead of waiting to be called up. There was some calculation in this decision since, if I remember right, a volunteer might be commissioned straight away whereas a conscript would not be able to avoid the presumed discomforts of 'the ranks'. Which of these two motives weighed more with me I would not at this distance of time like to say." (8)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Peter Calvocoressi was commissioned in RAF intelligence, and, in early 1941, he was sent to the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. (9) Bletchley was selected simply as being more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University since the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (10)

Peter Calvocoressi & Enigma

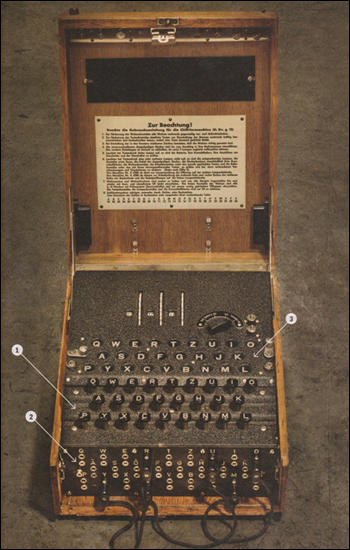

During the Second World War radio communication was a vital aspect of modern warfare. Radio was used for aerial, naval and mobile land warfare. However, it was very important that the enemy was not aware of these messages. Therefore all radio communications had to be disguised. The main task of the codebreakers was to read messages being sent by the German Enigma Machine. The situation was explained by Francis Harry Hinsley: "By 1937 it was established that... the German Army, the German Navy and probably the Air Force, together with other state organisations like the railways and the SS used, for all except their tactical communications, different versions of the same cypher system - the Enigma machine which had been put on the market in the 1920s but which the Germans had rendered more secure by progressive modifications." (11)

Peter Calvocoressi, explained in his book, Top Secret Ultra (1980), the task that faced the codebreakers. "Although its keyboard was simpler than a typewriter's, the Enigma machine was in all other respects much more complicated. Behind the keyboard the alphabet was repeated in another three rows and in the same order, but this time the letters were not on keys but in small round glass discs which were set in a flat rectangular plate and could light up one at a time. When the operator struck a key one of these letters lit up. But it was never the same letter. By striking P the operator might, for example, cause L to appear; and next time he struck P he would get neither P nor L but something entirely different. This operator called out the letters as they appeared in lights and a second operator sitting alongside him noted them down. This sequence was then transmitted by wireless in the usual Morse code and was picked up by whoever was supposed to be listening for it."

(2) Settings on the plugboard, in combination with the three rotors at the top,

determined the code. (3) With each key press, the corresponding coded (or decoded)

letter lit up on the output panel, allowing the operator to copy down the message.

Both the person sending and receiving the message had a handbook that told him what he had to do each day. This included the settings of the machine. As Calvocoressi pointed out: "These parts or gadgets consisted of a set of wheels rotors and a set of plugs. Their purpose was not simply to turn P into L but to do so in so complex a manner that it was virtually impossible for an eavesdropper to find out what had gone on inside the machine in each case. It is quite easy to construct a machine that will always turn P into L, but it is then comparatively easy to find out that L always means P; a simple substitution of this kind is inadequate for specially secret traffic. The eavesdropper's basic task was to set his machine in exactly the same way as the legitimate recipient of the message had set his, since the eavesdropper would then be able to read the message with no more difficulty than the legitimate recipient. The more complex the machine and its internal workings, the more difficult and more time-consuming was it for the eavesdropper to solve this problem.... Although only three wheels could be inserted into the machine at any one time, there were by 1939 five wheels issued with each machine. The operator had to use three of this set of five. He had to select the correct three and then place them in a prescribed order. This was crucial because the wheels, although outwardly identical, were differently wired inside." (12)

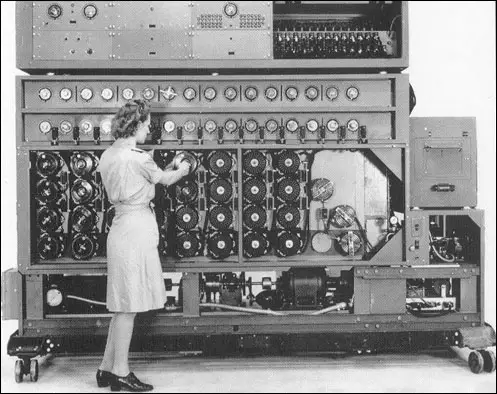

Alan Turing set about developing an engine that would increase the speed of the checking process. Turing finalized the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bombe") was in a copper-coloured cabinet. (13) "The result was a huge machine six-and-a-half feet tall, seven feet long and two feet wide. It weighed over a ton, with thirty-six 'scramblers' each emulating an Enigma machine and 108 drums selecting the possible key settings." (14) Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (15)

To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (16) The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. It was some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. (17) "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (18) They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (19)

Frederick Winterbotham was the chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (20)

A more improved version, called Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), was delivered on 8th August. From this point onwards, Bletchley Park was able to read, on a daily basis, every single Luftwaffe message - something in the region of one thousand a day. (21) At the time, the Battle of Britain was raging and the German codes were being broken at Bletchley Park, allowing the British to direct their fighters against incoming German bombers. When the battle was won the codebreakers intercepted messages cancelling the planned invasion of Britain - Operation Sea Lion. (22)

Peter and Barbara Calvocoressi, and their two sons, Paul and David, moved to Bletchley. According to The Guardian: "In 1943, appalled by their temporary lodgings, he and his wife (with their two young sons) bought a large house near Bletchley at a few hours' notice and lived there for the next 39 years. Music was a lifelong passion, and with the connivance of the Bletchley billeting officer he ensured his lodgers always had two violins, a viola and a cello to provide regular quartet concerts." By the end of the war he reached the rank of wing commander, and was seconded by British intelligence to Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. He interviewed many German commanders and, during the trial, cross-examined Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt in court. (23)

Publishing

In the 1945 General Election, Peter Calvocoressi stood as a Liberal Party candidate for Nuneaton. He finished third after his defeat he became a strong supporter of the Labour Party. In 1949 he began work at Chatham House under Arnold J. Toynbee where he wrote five volumes in the series of Annual Surveys of International Affairs. "Toynbee gave him responsibility for the annual Survey of International Affairs, meaning that he wrote a judicious but opinionated volume each year surveying world events. The experience taught him to write accurately, elegantly, and fast." (24)

In 1954 he became a partner in the publishing firms of Chatto & Windus and the Hogarth Press. In 1962 he was appointed as a member of the United Nations sub-committee on the prevention of discrimination and protection of minorities. Calvocoressi was also an active member of Amnesty International. In 1965 he took up the post of reader in international relations at Sussex University. In 1972 he returned to publishing as editorial director of Penguin Books. (25)

The Ultra Secret

Frederick Winterbotham approached the government and asked for permission to reveal the secrets of the work done at Bletchley Park. The intelligence services reluctantly agreed and Winterbotham's book, The Ultra Secret, was published in 1974. Those who had contributed so much to the war effort could now receive the recognition they deserved. (26) Unfortunately, some of the key figures such as Alan Turing and Alfred Dilwyn Knox were now dead.

Peter Calvocoressi now felt free to write about his activities and Top Secret Ultra was published in 1980. He was now considered an expert on British intelligence during the Second World War. He argued that Winston Churchill did not have advance warning on the bombing of Coventry on 14th November 1940. However, he was critical of the bombing of Dresden in February, 1945, saying that Bletchley Park had warned Allied air chiefs that, contrary to expectations, the SS Panzer army would not be returning through the city after the battle of the Ardennes. “The bombing of Dresden was terrible and should never have taken place.” (27)

Peter Calvocoressi died on 5th February 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra (1980)

When the war started I was a very unlikely candidate for Secret Intelligence. Although a British subject by birth owing to the accident of my having been born in India I was and am entirely Greek. My father, by an analogous accident, had been born a French citizen and had been brought up in Constantinople. He became a naturalised British subject during the First World War or soon after it but when I had wanted to join the diplomatic service after leaving Oxford in 1934 I was not acceptable. The rules said that a candidate had to be a British subject by birth, which I was, and the son of British-born parents, which I was not. How much less likely that I should ever be allowed into secret intelligence work. Not that I ever gave it a moment's thought, up to the very day when I found myself doing Ultra secret work.

Yet I was an insider as well as an outsider. I belonged to a community which was in most respects self-sufficient, but not in all. This was the close and prosperous inner community of Chiots which existed within the wider community of Greeks in London, Liverpool, Manchester and other such places. We were the descendants of those who had escaped westward at the time of the famous massacre on the island of Chios in 1822 (depicted by Delacroix and hymned by Victor Hugo).

These Chiots founded their own businesses and intermarried. Socially and professionally they lived their own lives, looking to one another for most of the goods and comforts needed between cradle and grave, including in particular jobs and spouses. But one thing they could not provide: education. So boys like myself were despatched into the English educational system. I went in more than half-Greek and came out more than half-English. This was a second migration. The first was geographical and forced on the Chiots by the massacre. The second was cultural, less forcible but ultimately no less fateful.

The education I received was excellent. Also, although I did not realise this at the time, it gave me a passport. Having emerged from Eton and Balliol I had become, potentially at least, Establishment material. I had also picked up a couple of secondary advantages in academic distinction (a scholarship at Eton and a First at Oxford) and a facility for languages. In the ordinary course of events I might be a somewhat disadvantaged member of the Establishment, endowed with a tongue twisting name and debarred from some kinds of official employment. But given a crisis the system would be flexible enough or desperate enough to take me right in.

In the autumn of 1939, twenty-six years old and recently married, I had even less wish than most people to rush off and risk my life. I was content to evade the conflict between family happiness and a wider duty by accepting the current orthodoxy which said that one should wait one's turn to be called up in an orderly manner and when required. I had been called to the Bar in 1935 and along with a number of other barristers I was temporarily recruited into the Ministry of Economic Warfare which was established in the London School of Economics off Aldwych in London. Its job was to find the bottlenecks in the German economy and squeeze them. Some optimists thought that in this way the German war machine could be brought to a halt by Christmas but this euphoria did not survive the test of experience and the Ministry, having been shifted to more commodious quarters in Berkeley Square, settled to a less spectacular but none the less useful role in the war.

Meanwhile my personal contribution began to seem shamefully jejune and when the phoney war was succeeded by disasters in the west in the spring of 1940 I decided I ought to do something more active than impede the neutrals' commerce with Germany. I resolved to volunteer for the army instead of waiting to be called up. There was some calculation in this decision since, if I remember right, a volunteer might be commissioned straight away whereas a conscript would not be able to avoid the presumed discomforts of 'the ranks'. Which of these two motives weighed more with me I would not at this distance of time like to say. Combined they led me to the War Office.

(2) The Daily Telegraph (5th February 2010)

As head of air intelligence at Station X - the top secret headquarters at Bletchley Park of the codebreakers who cracked Germany’s Enigma cipher during the Second World War - Calvocoressi played a critical role in the operation to intercept high-level German orders. This intelligence, known as Ultra, and provided by his team of mathematicians, linguists and other experts, not only helped win the Battle of Britain but also furnished details of Hitler’s proposed invasion in Operation Sea Lion, eventually abandoned as too risky.

Once the official secrets ban on the wartime operations at Bletchley Park had been lifted, Calvocoressi was at pains to repudiate the myth that Ultra had yielded advance information of the blitz on Coventry - “a good story that doesn’t lie down,” as he put it.

On the other hand he was always critical of the Allied bombing of Dresden, saying that Ultra had warned Allied air chiefs that, contrary to expectations, the SS Panzer army would not be returning through the city after the battle of the Ardennes. “The bombing of Dresden was terrible,” Calvocoressi declared long after the war, “and should never have taken place.”

His account of his wartime work at Bletchley Park, Top Secret Ultra, appeared in 1980. In it Calvocoressi emphasised the decisive role played by Ultra in intercepting communications: “Ultra took the blindfold off our eyes so that we could see the enemy in detail in a way in which he could not see us.”

The breaking of the Enigma machine ciphers gave Britain’s outnumbered fighter pilots a critical head start in intercepting German bombing raids. It also helped to end the Nazi wolfpack menace during the Battle of the Atlantic when, in December 1942, Bletchley Park experts cracked the U-boat cipher known as Triton.

(3) Ian Irvine, The Guardian (8th February 2010)

Peter Calvocoressi, who has died aged 97, was best known as an Ultra intelligence analyst at the Bletchley Park codebreaking centre in Buckinghamshire during the second world war, but this episode represented only four years in a long career with many different aspects. International affairs was an abiding interest. By his 96th birthday he had published his 20th book, the ninth edition of his World Politics Since 1945. Its 845 pages were a tribute to his lifelong energy, formidable memory and powers of analysis. Yet author and historian were only two of his job descriptions. He had been a barrister, a publisher, an academic and a journalist and, after Bletchley, he had assisted the prosecution at the Nuremberg war crimes trials.

He was born in Karachi, now in Pakistan. His parents were Greek (hailing from the Greek island of Chios, off the Turkish coast) and Peter's father was a merchant in the family business. When he was three months old, they moved to Liverpool, and he grew up in a community of prosperous, English-speaking Greek families.

In 1926 he sat the Eton scholarship examinations and was placed second – making him possibly the only Etonian with two great-grandfathers who had been slaves. He maintained that his education turned him "from a Greek in England into a Greek Englishman". At school he discovered a taste for history and his facility for languages, adding German and Italian to the English and French that he spoke at home. He took a first in history at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1934, hoping to join the diplomatic service, but his father's French birth debarred him. He consulted Anthony Eden, only to be told that he would never get anywhere with his surname. Instead, in 1935 he became a barrister specialising in chancery law, and three years later married Barbara Eden, the daughter of Lord Henley.

The second world war transformed his life, although at a War Office interview, he saw a note on his file: "No good for anything – not even intelligence." However he was commissioned in RAF intelligence, and, in early 1941, found himself at Bletchley. He spent the rest of the war as deputy head (and from December 1944 head) of a small, secret section dealing with Luftwaffe Ultra intelligence, translating and interpreting decrypted Enigma signals. This enterprise remained a secret until the 1970s, after which Calvocoressi wrote its history in Top Secret Ultra (1980).

Outside the North African campaigns and in the battle against U-boats in the Atlantic, he felt that claims for Ultra's importance had been exaggerated, though admitting the psychological advantage of knowing the German order of battle: "It took the blindfold off our eyes, so that we could see the enemy in detail as he could not see us."

In 1943, appalled by their temporary lodgings, he and his wife (with their two young sons) bought a large house near Bletchley at a few hours' notice and lived there for the next 39 years. Music was a lifelong passion, and with the connivance of the Bletchley billeting officer he ensured his lodgers always had two violins, a viola and a cello to provide regular quartet concerts.

In the 1945 general election, Peter stood as a Liberal candidate, but lost in the Labour landslide. From 1950 onward, he unhesitatingly voted Labour in every general election. Later in 1945, now with the rank of wing commander, he was seconded by British intelligence to Nuremberg. He interviewed many German commanders and, during the trial, cross-examined Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt in court.

His wartime experience made him unwilling to return to his prewar life at the bar. For five years from 1949 he worked at Chatham House, writing five volumes in the series of Annual Surveys of International Affairs begun by Arnold Toynbee. In 1954 he became a partner in the publishing firms of Chatto & Windus and the Hogarth Press.

He continued to take public roles. In the 1950s and 60s, he was a member and later chairman of the Africa Bureau, founded by his friend David Astor, proprietor and editor of the Observer, as a political lobby concerned with apartheid in South Africa and decolonisation. From 1962 to 1971 he was a member of the United Nations sub-committee on the prevention of discrimination and protection of minorities. In the late 1960s he was asked to arbitrate on internal disputes at Amnesty International that threatened to destroy the organisation. He was always proud of his successful intervention, and that Amnesty survived.

In 1965 he left publishing to take up the post of reader in international relations at Sussex University that was created for him. In 1972 he was enticed back by the offer of the newly created post of editorial director of Penguin Books. He was later appointed publisher and chief executive, but in a series of disputes with the owners, Pearson Longman, he was obliged to resign in 1976.

In 1990 he received an honorary doctorate from the Open University for his direction of its publishing division in the 1980s (later sold for a handsome profit). He continued writing books, including the two volumes of the Penguin History of the Second World War and Who's Who in the Bible (despite being a lifelong atheist).

Barbara died in 2005 and the following year he married Rachel Scott. They lived in London and in Dorset, where he died. He is survived by his sons, Paul and David, and by three grandchildren.

(4) Jonathan A. Bush, The Independent (20th February 2010)

Peter Calvocoressi was a senior intelligence officer at Bletchley Park who was picked soon after the war to lead a team of experts on the German military at the Nuremberg war crimes trial.

For almost six decades he was a distinguished author, urbane publisher, and human rights activist, but those two early activities – Bletchley Park cryptanalysis and Nuremberg prosecutions, military realities and an idealistic claim to justice – framed his long and diverse career.

He was a child of the Greek diaspora, born in Karachi in November 1912, to parents descended from mercantile families from Chios. When Peter was three months old his father was assigned to Liverpool, where his parents raised him and two sisters in a cosmopolitan cocoon. He grew up with Greek friends, spoke French at home as well as English and had family trips to Italy and Greece.

A King's Scholar at Eton, he focused on history and German. In 1931 he moved on to Balliol, having been passed over for a scholarship in favor of the future historian and master Christopher Hill. While in Oxford Calvocoressi avoided politics, later saying he never even knew the location of the Oxford Union. He focused on Modern History, and had as tutors V. H. Galbraith and Sir Lewis Namier, whose knowledge of European politics characterised his own later writings.

Leaving Oxford with a First, Calvocoressi went to London with a view to joining the diplomatic service. Learning that his father's French birth would preclude him, father and son secured an audience with Anthony Eden, then a minister in the Foreign Office. Eden confirmed his ineligibility and added that with so distinctive a Greek name he could never rise to the top. Calvocoressi turned to law. He joined an equity chambers in Lincoln's Inn. Shy but a good dancer, he met Barbara Eden, daughter of Lord Henley, and in 1938 they married.

Everybody at Bletchley Park had a story about how they were plucked from classics or mathematics. Calvocoressi was serving in the Ministry of Economic Warfare reviewing shipping manifests. In 1940 he tried to volunteer for the War Office but was rejected because of a head injury he had sustained in a car accident in which his mother died. He took umbrage at the reason listed on his file: "No good, not even for Intelligence." Through a connection he applied to the Air Ministry and was accepted by the Intelligence division. He was sent to RAF bases in Northumberland to brief pilots but soon recalled to London and sent to Bletchley Park.

Calvocoressi was assigned to Hut 3A to work on "Ultra," the decodes of Luftwaffe messages sent over Enigma machines. Luftwaffe units relied more than other services on Enigma, and their principal cipher, Red, "was broken daily [without interruption from May 1940], usually on the day in question and early in the day. Later in the war I remember that we in Hut 3 would get a bit techy if Hut 6 had not broken Red by breakfast time."

Calvocoressi's job was to study decrypted messages and fill in gaps, decide their meaning, weigh their urgency and decide on the recipients. In a typical eight-hour shift, Hut 3 might produce 30 decodes. For most of the war the Hut was led by Eric Jones, a Midlands manufacturer who went on to a brilliant career in intelligence, with E.J.B. ("Jim") Rose as the head of 3A and Calvocoressi his deputy.

Calvocoressi impressed colleagues as competent, less ebullient than Rose but calm and erudite. When American cryptanalysts were introduced in mid-1943, he worked easily with them and formed lifelong friendships with their chief, Colonel Telford Taylor, Robert Slusser, later a leading Sovietologist, and eventual Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell. After lodging in a series of unsatisfactory billets, Calvocoressi bought the roomy 18th-century Guise House. For the rest of the war he hosted seven or eight personnel, including Americans, giving preference to those who could play musical instruments.

Leadership of Hut 3A brought special responsibilities. After the setback in the Ardennes in December 1944, Calvocoressi and the renowned Cambridge classicist F.L. Lucas, later President of the British Academy, were assigned to investigate if Ultra had failed or if its recipients in the SHAEF and Army Group headquarters had failed to use it. He concluded that Bletchley Park had accurately outlined German preparations since August, though not the timing, and that commanders had been lulled into thinking too far ahead. Lucas and Calvocoressi "expected heads to roll at Eisenhower's HQ but they did no more than wobble."

A more difficult question was presented when the former 3A chief Jim Rose, now at the Air Ministry, heard of plans to bomb Dresden. He went to the US commander Carl Spaatz, who agreed to cancel the raid if evidence revealed no military targets, and Air Marshal Harris agreed. Rose called Calvocoressi, his successor in Hut 3A, who stressed that Panzer units were not being routed near Dresden and that the city should not be bombed. But British Bomber Command spurned Rose and the Calvorocessi estimate, with terrible consequences.

After V-E Day Calvocoressi stood in the General Election as Liberal candidate for Nuneaton, a Labour seat where he increased his party's tally but finished third.

Days later he received overtures from his friend Taylor, now working on the American case for Nuremberg. US planners had realised that direct evidence might be lacking against some perpetrators and that the Nazi state operated through institutions as well as individuals. The answer to both issues was a proposal by Colonel Murray Bernays to charge organisations as well as leaders; if an entity were found guilty, prosecutors could then charge leaders with criminal membership if murder charges were impossible. Most planners assumed that the guilty would include the military high command as well as the Party and SS. Taylor convinced his chief, Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, that they presently lacked evidence against the military but that Calvocoressi was the ideal man to find it.

In January 1946, with Calvocoressi at his side, Taylor presented the case against the High Command, using testimony from SS General Erich Bach-Zelewski, who led anti-partisan campaigns. One historian later complained that the two men went easy on Bach-Zelewski, but contemporaries praised them for Taylor's eloquence and because he and Calvocoressi had a major perpetrator testify without promising immunity or compromising later charges.

Later, Taylor was chosen to lead further American trials in Nuremberg. He turned again to Calvocoress. Taylor sent him and three researchers to Washington, where for months he supervised the archiving of captured military records. The evidence they processed provided the basis for convictions including those involving atrocities in the Balkans and Norway.

The plan, was that the British would also commence major trials but they balked, yielding to Foreign and War Office pressure and rejecting Shawcross's hopes, American overtures and Calvocoressi's evidence.

Now came the question of a peacetime career. Calvocoressi wanted work involving public affairs, but a brief return to the bar and his parliamentary defeat convinced him to find a different route. For a few years he ran a fledgling Liberal International but found it unworkable. He wrote his first book, a survey of Nuremberg that is more thoughtful than most. An offer came to lead a new press organisation based in Geneva, but he turned it down, recommending Jim Rose.

In 1949 Calvocoressi joined the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the think tank in Chatham House founded by Arnold Toynbee. Toynbee gave him responsibility for the annual Survey of International Affairs, meaning that he wrote a judicious but opinionated volume each year surveying world events. The experience taught him to write accurately, elegantly, and fast.

After five years and 10 hefty volumes, Calvocoressi left Chatham House and became a partner at Chatto & Windus, which had published his Nuremberg book. Calvocoressi helped build up its annual turnover from £200,000 to £500,000. It had absorbed the Hogarth Press, whose guiding spirit was Leonard Woolf. Calvocoressi came to admire Woolf deeply, calling him "the only man I ever met who seemed to me to be right about everything that mattered" and taking to heart the older man's editorial maxim that "there never was a book which could not be improved by cutting."

He was writing extensively on international relations – a weekly column for provincial newspapers begun while he was at Chatham House led to a book on Suez and a follow-up 10 years later; a monograph on the public reaction to the Sharpeville massacre; and a general study of world order in the age of decolonialisation. He left Chatto & Windus in 1966 for a Readership in International Relations at Sussex. Teaching gave him enormous satisfaction, but when the opportunity arose five years later to become editorial director of Penguin Books, he could not resist.

The challenge was to strengthen its position, as Calvocoressi said, as a place "for top people to write little books about big subjects for large audiences". But his tenure came to grief when Pearsons bought Penguin with Calvocoressi's support ("perhaps the biggest misjudgment of my life") then squeezed him out. He resumed writing and was hired by the Open University, which saw the possibility of a university press that might turn the material prepared by its faculty into books for the public. Calvocoressi supervised the effort, leaving with an honorary degree in 1990.

From 1962 to 1971 he was a member of the UN Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. His Balliol friend David Astor asked him in 1963 to chair the Africa Bureau, a study group, and like Rose, Calvocoressi was soon writing about apartheid and racism.

From 1961 to 1971 he was on the Council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies founded by his friend Alistair Buchan, and he was twice invited to lead Chatham House. Brought to Amnesty International to mediate an internal dispute, he served on its executive board from 1969 to 1971. And he found time for political campaigns with a more personal connection: he commissioned, and wrote a sympathetic introduction to, an account of Zionist settlers who were British spies in the First World War. He protested against the 1967 coup of the Greek Colonels. But at least as important to the long-time editor must have been his tenure as chair of the London Library from 1970 to 1973.

He continued to write prolifically – his survey of the Second World War is regarded, along with Gerhard Weinberg's, as the best general study of its kind; an elegant account of Ultra intelligence at Bletchley Park; and a "Who's Who" of characters in the Bible that surprised friends who knew of his fierce atheism. He wrote a foreign-relations study of Africa, a study of peace from the Gospel to the UN, and a study of Europe's terrible 20th century and improving prospects with the end of the Cold War. Each book showed his breadth, erudition, concision – his lesson from Leonard Woolf.

In his 96th year, he published a new edition of his survey of world politics, characterised again by tart, far-sighted judgments. He would have made a superb chief of policy in the Foreign Office had his Greek surname not led Anthony Eden to steer him away.

Peter John Ambrose Calvocoressi, intelligence officer and writer: born Karachi 17 November 1912; married 1938 Barbara Eden (died 2005; two sons), 2006 Margaret Scott; died Devon 5 February 2010.