Frederick Winterbotham

Frederick Winterbotham, the younger child and only son of Frederick Winterbotham and his wife Florence Vernon Graham, was born in Stroud, Gloucestershire, on 16th April, 1897. His father was a solicitor in Painswick. He was educated at Charterhouse School.

On the outbreak of the First World War he joined the British Army. In 1916 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and became a pilot. Winterbotham was shot down over Passchendaele on 13th July 1917. He was reported as killed in action but he survived but was not released until after the Armistice. (1)

In 1918 he went to Christ Church to study law. He left Oxford University after obtaining his BA in 1920. Winterbotham spent nine years in Kenya and Rhodesia as a pedigree stock breeder. He returned to England in 1929. Winterbotham considered becoming a stockbroker before joining the staff of the Royal Air Force, where he was assigned to the newly created Air Section of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6).

Frederick Winterbotham - Nazi Germany

In March 1934 Winterbotham visited Nazi Germany and had an interview with Adolf Hitler and Alfred Rosenberg. He used the cover story that he was "persuading people in Britain to see things the Nazi way", but in actuality spying on German developments in air warfare. According to Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service (2010): "Winterbotham... made his number with several senior Nazis, met young Luftwaffe pilots and successfully established himself with them as a friendly face. On his return Winterbotham reported on the Germans' unmistakeable plans to develop a first-class, modern air force." (2)

In 1940 Winterbotham moved to the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, to work on the penetration of German ciphers encoded by the Enigma machine. A cryptanalyst at Bletchley, R. V. Jones, later explained their task. "This was a very ingenious arrangement of three wheels, each one of which had a sequence of studs on each side, with each stud on one side being connected by a wire to a pin on the other side - the exact arrangement of the connections being one of the secrets of the machine and the pin making contact with one of the studs on the next wheel. The machine had a typewriter keyboard, and it was worked rather like a cyclometer: every time the machine was operated to encode a letter, one wheel would be turned by one space; after this wheel had moved by enough spaces to turn it through one revolution, it would click its neighbouring wheel by one space. The wheels were thus never in the same position twice. The basic encoding was effected by the passage of an electric current through the studs so that when a letter was to be encoded, the appropriate key would be pressed on the keyboard, and the resultant coded letter would be determined by the appropriate conducting path through the studs, the studs on one wheel making suitable contact with the pins on the neighbouring wheel. A further touch of ingenuity was to add a reversing arrangement at the edge of the third wheel, again with studs cross-connected so as to send the current backwards through the wheels by yet another path. The returning current lit a small electric bulb which illuminated a particular letter on a second keyboard, and thus indicated the enciphered equivalent of the letter whose key had originally been pressed." (3)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

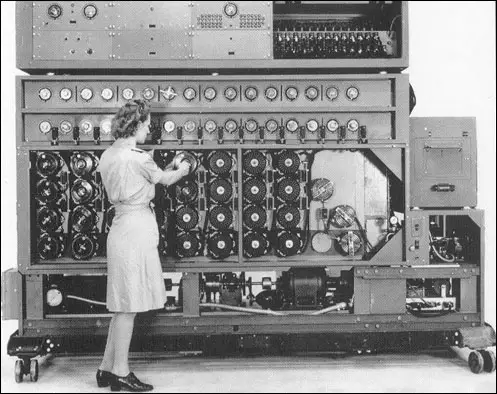

Alan Turing set about developing an engine that would increase the speed of the checking process. Turing finalised the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bomb") was a copper-coloured cabinet that was two metres tall, two metres long and a metre wide. Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (4)

The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (5) A more improved version, called Agnes, was delivered on 8th August. Over the next few months 178 messages were broken on the two machines. They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (6)

Frederick Winterbotham later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (7)

Bletchley Park

According to his biographer, Christine Nicholls, Winterbotham played an important role at Bletchley Park in communicating information to the Royal Air Force: "The Luftwaffe signals were broken; the next step was to convey the information to commanders in the field. Winterbotham devised and supervised the special liaison units of young officers and technical sergeants stationed at battle command headquarters, who received enciphered radio messages from Bletchley (Ultra) and communicated them to the commanders. He was also the route by which Ultra intelligence reached the prime minister. His other role was, upon Winston Churchill's instructions, to indoctrinate American commanders before they could receive Ultra messages, for Churchill was concerned about the security of the Ultra system when America joined the war." (8) During this period Winterbotham became known to and respected by the American military leaders - Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, and Karl Spaatz.

In March 1944 the allies signed an agreement to unify the handling of Ultra intelligence throughout the world. It has been claimed that the deal was negotiated by Winterbotham. From 1945 to 1948 he worked for the British Overseas Airways Corporation. After retirement he ran a small farm in Devon and married for a fourth time.

Winterbotham approached the government and asked for permission to reveal the secrets of the work done at Bletchley Park. The intelligence services reluctantly agreed and Winterbotham's book, The Ultra Secret, was published in 1974. Those who had contributed so much to the war effort could now receive the recognition they deserved. (9) Unfortunately, some of the key figures such as Alan Turing and Alfred Dilwyn Knox were now dead.

Frederick Winterbotham died on 28th January 1990 at his cottage, West Winds, Blandford Forum, Dorset.

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Winterbotham, The ULTRA Secret (1974)

It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)