Mavis Batey

Mavis Lever, the daughter of a postal worker and a seamstress, was born in Dulwich, London, on 5th May 1921. She was a talented linguist and after passing her German O Level she persuaded her parents to take her to Germany on holiday. She was studying German Literature at University College when the Second World War broke out. (1)

Mavis later recalled: "I didn't want to go on with academic studies. University College was just evacuating to the campus at Aberystwyth, in west Wales. But I thought I ought to do something better for the war effort than reading German poets in Wales. After all, German poets would soon be above us in bombers. I remarked to someone that I should train to be a nurse." Her friend suggested that her very good German might be of use to the government. (2)

Mavis joined the Ministry of Economic Warfare. Her first task was checking the personal columns of The Times for coded messages. (3) She also did other work such as "blacklisting all the people who were dealing with Germany - through commodies they were using." Soon afterwards she was asked to visit the Foreign Office: "I got called for the interview at the Foreign Office - conducted by a formidable lady called Miss Moore - I don't know whether she knew what we were going to do. At the time of the interview, we didn't know whether we were going to be spies or what. But then I got sent to Bletchley." (4)

Bletchley Park

Mavis was sent to the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. Bletchley was selected simply as being more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University since the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (5)

During the Second World War radio communication was a vital aspect of modern warfare. Radio was used for aerial, naval and mobile land warfare. However, it was very important that the enemy was not aware of these messages. Therefore all radio communications had to be disguised. The main task of the codebreakers was to read messages being sent by the German Enigma Machine. The situation was explained by Francis Harry Hinsley: "By 1937 it was established that... the German Army, the German Navy and probably the Air Force, together with other state organisations like the railways and the SS used, for all except their tactical communications, different versions of the same cypher system - the Enigma machine which had been put on the market in the 1920s but which the Germans had rendered more secure by progressive modifications." (6)

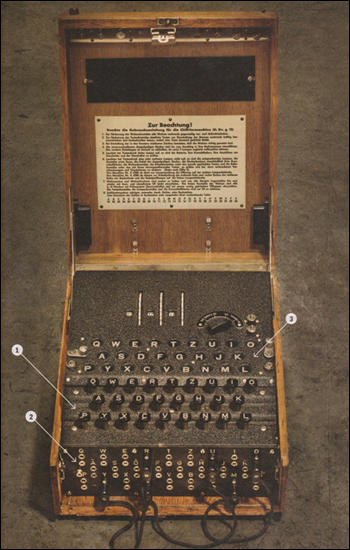

Peter Calvocoressi, explained in his book, Top Secret Ultra (1980), the task that faced the codebreakers. "Although its keyboard was simpler than a typewriter's, the Enigma machine was in all other respects much more complicated. Behind the keyboard the alphabet was repeated in another three rows and in the same order, but this time the letters were not on keys but in small round glass discs which were set in a flat rectangular plate and could light up one at a time. When the operator struck a key one of these letters lit up. But it was never the same letter. By striking P the operator might, for example, cause L to appear; and next time he struck P he would get neither P nor L but something entirely different. This operator called out the letters as they appeared in lights and a second operator sitting alongside him noted them down. This sequence was then transmitted by wireless in the usual Morse code and was picked up by whoever was supposed to be listening for it."

(2) Settings on the plugboard, in combination with the three rotors at the top,

determined the code. (3) With each key press, the corresponding coded (or decoded)

letter lit up on the output panel, allowing the operator to copy down the message.

Both the person sending and receiving the message had a handbook that told him what he had to do each day. This included the settings of the machine. As Calvocoressi pointed out: "These parts or gadgets consisted of a set of wheels rotors and a set of plugs. Their purpose was not simply to turn P into L but to do so in so complex a manner that it was virtually impossible for an eavesdropper to find out what had gone on inside the machine in each case. It is quite easy to construct a machine that will always turn P into L, but it is then comparatively easy to find out that L always means P; a simple substitution of this kind is inadequate for specially secret traffic. The eavesdropper's basic task was to set his machine in exactly the same way as the legitimate recipient of the message had set his, since the eavesdropper would then be able to read the message with no more difficulty than the legitimate recipient. The more complex the machine and its internal workings, the more difficult and more time-consuming was it for the eavesdropper to solve this problem.... Although only three wheels could be inserted into the machine at any one time, there were by 1939 five wheels issued with each machine. The operator had to use three of this set of five. He had to select the correct three and then place them in a prescribed order. This was crucial because the wheels, although outwardly identical, were differently wired inside." (7)

Alfred Dilwyn Knox

Mavis worked very closely with Alfred Dilwyn Knox. "We were all thrown in the deep end. No one knew how the blessed thing worked. When I first arrived, I was told, 'We are breaking machines, have you got a pencil? And that was it. You got no explanation. I never saw an Enigma machine. Dilly Knox was able to reduce it - I won't say to a game, but a sort of linguistic puzzle. It was rather like driving a car while having no idea what goes on under the bonnet." (8) "We were looking at new traffic all the time or where the wheels or the wiring had been changed, or at other new techniques. So you had to work it all out yourself from scratch.” (9)

Knox admitted that he liked employing women. According to Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010): "Dilwyn Knox... found that women had a greater aptitude for the work required - as well as nimbleness of mind and capacity for lateral thought, they possessed a care and attention to detail that many men might not have had. This of course is just speculation; the other possibility, and one that seems likely considering the scratchiness of many of Knox's personal dealings, was that he simply did not like men very much." (10) Knox was so impressed with Mavis Lever's work that in August 1940, that he contacted head office: "Miss Lever is the most capable and the most useful and if there is any scheme of selection for a small advancement in wages, her name should be considered." (11)

Soon after arriving at Bletchley Park Mavis met Keith Batey. One day she had to convey an operational message to convey to Hut 3. He later recalled: "Late one evening. I was in the hut, on the evening shift, and that's how I met her. This little girl arrived from Dilly's outfit with this message or problem - she didn't know how to solve it." It was several months before they became what she called an "item". Although people from different units were not allowed to have "conversations concerning work" there were no rules against "courting". (12)

Knox encouraged all his assistants to look at problems from unexpected angles. Knox would ask new arrivals which way the hands of a clock went round. (13) When they answered "clockwise" Knox would reply that that would depend on whether one was the observer, or the clock. Although most of the codebreakers were mathematicians Knox believed that this caused them problems as "mathematicians are very unimaginative". (14)

Mavis Lever worked with Knox on the "updated Italian Naval Enigma machine, checking all new traffic and even the wheels, cogs and wiring to see how it was constructed." (15) In March 1941 she deciphered a message, “Today 25 March is X-3". She later recalled that "if you get a message saying 'today minus three', then you know that something pretty big is afoot." Working with a team of intelligence analysts she was able to work out that the Italian fleet was planning to attack British troop convoys sailing from Alexandria to Piraeus in Greece. As a result of this information the British Navy was able to ambush four Italian destroyers and four cruisers off the coast of Sicily. Over 3,000 Italian sailors died during the Battle of Cape Matapan. Admiral John Henry Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence, sent a message to Bletchley Park: "Tell Dilly (Knox) that we have won a great victory in the Mediterranean and it is entirely due to him and his girls." (16)

Mavis's boyfriend, Keith Batey, felt guilty about working at Bletchley Park, while so many of his contemporaries were risking their lives in open combat. "Accordingly he told his bosses that he wanted to train as a pilot, only to be informed that no one who knew that the British were breaking Enigma could be allowed to fly in the RAF, the risk being that he might be shot down and captured. Batey then suggested that he join the Fleet Air Arm, flying over the sea in defence of British ships, arguing that he would be either killed or picked up by his own side. Worn down by his persistence, his superiors reluctantly agreed." The couple married in November, 1942, shortly before Batey left for Canada for the Fleet Air Arm advanced flying course. (17)

Mavis Batey and D-Day

Mavis Batey played a very important role in breaking of the Enigma cipher used by the German secret service, the Abwehr. This was a vital aspect of what became known as the Double-Cross System (XX-Committee). Created by John Masterman, it was an operation that attempted to turn "German agents against their masters and persuaded them to cooperate in sending false information back to Berlin." (18) Masterman needed to know if the Germans believed the false intelligence they were receiving.

Mavis was part of a team that included Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Margaret Rock that broke the Abwehr Enigma. "On December 8 1941 Mavis Batey broke a message on the link between Belgrade and Berlin, allowing the reconstruction of one of the rotors. Within days Knox and his team had broken into the Abwehr Enigma, and shortly afterwards Mavis broke a second Abwehr machine, the GGG, adding to the British ability to read the high-level Abwehr messages and confirm that the Germans did believe the phony Double-Cross intelligence they were being fed by the double agents." (19)

This Double-Cross operation became very important during the proposed D-Day landings. The deception plan had been devised by Tomás Harris and carried out by double-agent, Juan Pujol: "The key aims of the deception were: "(a) To induce the German Command to believe that the main assault and follow up will be in or east of the Pas de Calais area, thereby encouraging the enemy to maintain or increase the strength of his air and ground forces and his fortifications there at the expense of other areas, particularly of the Caen area in Normandy. (b) To keep the enemy in doubt as to the date and time of the actual assault. (c) During and after the main assault, to contain the largest possible German land and air forces in or east of the Pas de Calais for at least fourteen days." (20)

Harris devised a plan of action for Pujol (code-named GARBO). He was to inform the Germans that the opening phase of the invasion was under way as the airborne landings started, and four hours before the seaborne landings began. "This, the XX-Committee reasoned, would be too later for the Germans to do anything to do anything to frustrate the attack, but would confirm that GARBO remained alert, active, and well-placed to obtain critically important intelligence." (21)

Christopher Andrew has explained how the strategy worked: "During the first six months of 1944, working with Tomás Harris, he (GARBO) sent more than 500 messages to the Abwehr station in Madrid, which as German intercepts revealed, passed them to Berlin, many marked 'Urgent'... The final act in the pre-D-Day deception was entrusted, appropriately, to its greatest practitioners, GARBO and Tomás Harris. After several weeks of pressure, Harris finally gained permission for GARBO to be allowed to radio a warning that Allied forces were heading towards the Normandy beaches just too late for the Germans to benefit from it." (22)

It was later pointed out: "The false intelligence led the Germans to believe that the main force would land on the Pas de Calais rather than in Normandy. As a result Hitler insisted that two key armoured divisions were held back in the Calais area.... Brigadier Bill Williams, Montgomery’s chief intelligence officer, said that without the break into the Abwehr Enigma the deception operation could not have been mounted. The forces in Calais would have moved to Normandy and could well have thrown the Allies back into the sea." (23)

After the war, she gave up work to bring up her three children, Elizabeth, Christopher and Deborah. She later told Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010): "I didn't really get back into any kind of intellectual activity until my three children were grown. After that, I could go to the Bodleian Library every day. so i eventually picked up." (24)

Historical Gardens

In 1967 Keith Batey became chief financial officer of Oxford University, and they lived on the university's Nuneham Park estate where the gardens, landscaped in the 18th century, had become overgrown. While researching the estate, Mavis Batey developed to an interest in historical gardens. Over the next few years she " became an immensely inspirational force behind moves" by the Campaign to Protect Rural England and English Heritage to protect these gardens. (25)

Mavis Batey became honorary secretary of the Garden History Society from 1971 until 1985, then its honorary president. She also wrote several books on historical gardens, including Jane Austen and the English Landscape (1996) and Alexander Pope: Poetry and Landscape (1999). She also published an affectionate biography of Alfred Dilwyn Knox, entitled Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2010). She advised Kate Winslet on what it was like to be a female codebreaker, for the film Enigma.

Mavis Batey, died aged 92, on 12th November 2013.

Primary Sources

(1) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

Mavis Batey vividly recalls the V-1 rockets and the means by which the codebreakers at Bletchley Park sought to thwart them. "We were working on double agents all the time, giving misinformation to their controllers. And because we could read the Enigma, we could see how they were receiving this misinformation. One of the things when the Vls started was that the double agent was asked to give a report to the Germans on where the rockets were falling. Because of course they were wanting them to fall on central London.

"At that point, the bombs werefalling in central London so intelligence here wanted them to cut out at a different point. So this double agent was instructed to tell his masters that they were falling north of London. The result of this was that the Germans cut the range back a little and as a result, the rockets started falling in south London. Just where my parents lived."

In this case, it seemed that to Mrs Batey at least, ignorance was preferable to any other state; for security reasons, she knew nothing of this double-cross operation, or the messages that confirmed its success. "I had no idea and it is just as well that I didn't. So when I saw the devastation at Norbury, I did not know that it had anything to do with anything I was doing. It really would have been a terrible shock to know that."

(2) Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (2002)

Dilly himself always slept in the office, going back to Courn's Wood once a week. His driving was worse than ever. His mind was totally elsewhere. Fortunately he drove slowly. "It's amazing how people smile, and apologise to you, when you knock them over," he remarked.

In time the buildings inside the Park walls extended into blocks of huts and cafeterias, and by the end of the war the personnel numbered more than seven thousand, increased by observers and liaison men and important visitors in uniform. With all this Dilly had nothing to do. At first his department consisted of ten people, though these included, besides Peter Twinn, two very brilliant and sympathetic young women, Margaret Rock and Mavis Lever (now Mrs Batey). They were accommodated in a small cottage overlooking the old stable yard.

He would, however, need more ciphering clerks-not the vast numbers which eventually made the Treasury complain that "Bletchley was using up all the girls in the country," but still, a section of his own. Into this task Dilly entered with quite unexpected enthusiasm, and when the assistants arrived down from London with the files they were surprised to find him surrounded with pretty girls, all of them, for some reason, very tall, whom he had recruited for the work. The girls took from four to six months to train, though this was not undertaken by Dilly, who never trained anybody, but by a capable and understanding woman, Mrs Helen Morris. They worked on the equations in three eight-hour shifts, and when Dilly wanted to speak to them or to the punch-card operators who registered the encipherments as dots, he would limp across from the cottage, often in his grey dressing gown, indifferent to rain and snow, to tell them his new idea.

(3) The Daily Telegraph (13th November, 2013)

Mavis Batey, who has died aged 92, was one of the leading female codebreakers at Bletchley Park, cracking the Enigma ciphers that led to the Royal Navy’s victory at Matapan in 1941.

She was the last of the great Bletchley “break-in” experts, those codebreakers who found their way into new codes and ciphers that had never been broken before.

Mavis Batey also played a leading role in the cracking of the extraordinarily complex German secret service, or Abwehr, Enigma. Without that break, the Double Cross deception plan which ensured the success of the D-Day landings could never have gone ahead....

She initially worked in London, checking commercial codes and perusing the personal columns of The Times for coded spy messages. After showing promise, she was plucked out and sent to Bletchley to work in the research unit run by Dilly Knox.

Knox had led the way for the British on the breaking of the Enigma ciphers, but was now working in a cottage next to the mansion on new codes and ciphers that had not been broken by Hut 6, where the German Army and Air Force ciphers were cracked.

“It was a strange little outfit in the cottage,” Mavis said. Knox was a true eccentric, often so wrapped up in the puzzle he was working on that he would absent-mindedly stuff a lunchtime sandwich into his pipe rather than his tobacco:

“Organisation is not a word you would associate with Dilly Knox. When I arrived, he said: 'Oh, hello, we’re breaking machines, have you got a pencil?’ That was it. I was never really told what to do. I think, looking back on it, that was a great precedent in my life, because he taught me to think that you could do things yourself without always checking up to see what the book said.

“That was the way the cottage worked. We were looking at new traffic all the time or where the wheels or the wiring had been changed, or at other new techniques. So you had to work it all out yourself from scratch.”

Although only 19, Mavis began working on the updated Italian Naval Enigma machine and, in late March 1941, broke into the system, reading a message which said simply: “Today’s the day minus three.” “Why they had to say that I can’t imagine,” she recalled. “It seems rather daft, but they did. So we worked for three days. It was all the nail-biting stuff of keeping up all night working. One kept thinking: 'Well, would one be better at it if one had a little sleep or shall we just go on?’ - and it did take nearly all of three days. Then a very, very large message came in.”

The Italians were planning to attack a Royal Navy convoy carrying supplies from Cairo to Greece, and the messages carried full details of the Italian plans for attack: “How many cruisers there were, and how many submarines were to be there and where they were to be at such and such a time, absolutely incredible that they should spell it all out.”

The intelligence was phoned through to the Admiralty and rushed out to Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet. “The marvellous thing about him was that he played it extremely cool,” Mavis said. “He knew that they were going to go out and confront the Italian fleet at Matapan but he did a real Drake on them.”

The Japanese consul in Alexandria was sending the Germans reports on the movement of the Mediterranean Fleet. The consul was a keen golfer, so Cunningham ostentatiously visited the clubhouse with his clubs and an overnight bag. “He pretended he was just going to have the weekend off and made sure the Japanese spy would pass it all back,” Mavis recalled. “Then, under cover of the night, they went out and confronted the Italians.”

In a series of running battles over March 27/28 1941, Cunningham’s ships attacked the Italian vessels, sinking three heavy cruisers and two destroyers. Without radar, the Italians were caught completely by surprise, and 3,000 of their sailors were lost.

(4) Michael Smith, The Guardian (20th November, 2013)

Mavis Batey, who has died aged 92, was often described as one of the top female codebreakers at Bletchley Park but, while she was always too modest to make the point herself, this diminished her role. She was one of the leading codebreakers of either sex, breaking the Enigma ciphers that led to the Royal Navy's victory over Italy at Matapan in 1941 and, crucially, to the success of the D-day landings in 1944.

She was 19 years old when she was sent to Bletchley, the codebreaking centre in Buckinghamshire, in early 1940 and put to work in No 3 Cottage, in the research section, which broke into new cipher systems that had never been broken before. It was run by the veteran codebreaker and Greek scholar Dilly Knox, who had not only broken the Zimmermann Telegram, which brought the US into the first world war, but had also pieced together the mimes of the Greek playwright Herodas from papyri fragments found in an Egyptian cave.

In March 1941, Mavis broke a series of messages enciphered on the Italian navy's Enigma machine that revealed the full details of plans to ambush a Royal Navy supply convoy ferrying supplies from Egypt to Greece. The plans gave Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet, the opportunity to turn the tables on the Italians, who were taken completely by surprise. Cunningham's ships sank three heavy cruisers and two estroyers with the loss of 3,000 Italian sailors. The Italian fleet never confronted the Royal Navy again.

Cunningham visited the cottage to thank Knox and his team of young female codebreakers. "The cottage wall had just been whitewashed," Mavis recalled. "Someone enticed the admiral to lean against it so he got whitewash on his lovely dark blue uniform. We tried not to giggle when he left."

(5) Martin Childs, The Independent (24th November 2013)

Mavis Batey was a garden historian and conservationist, but unknown to many until recently, was also one of the leading female Bletchley Park codebreakers whose skills in decoding the German Enigma ciphers proved decisive at various points of the war. On the outbreak of war she broke off her German studies to enlist as a nurse, but was told she would be more use as a linguist. She had hoped to be a Mata Hari-esque spy, seducing Prussian officers, but, she said, “I don’t think either my legs or my German were good enough, because they sent me to the Government Code & Cipher School.”

Batey was the last of the Bletchley “break-in” experts – codebreakers who cracked new codes and ciphers. She unravelled the Enigma ciphers that led to victory in the Battle of Cape Matapan in 1941, the Navy’s first fleet action since Trafalgar, and played a key role in breaking the astonishingly complex Abwehr (German secret service) Enigma. Without this, the Double Cross deception plan which ensured the success of D-Day could not have gone ahead....

Batey began working on the updated Italian Naval Enigma machine, checking all new traffic and even the wheels, cogs and wiring to see how it was constructed. She reconstructed the wiring from the machine to discover a major machine flaw that helped her team break even more coded messages. “You had to work it all out yourself from scratch,” she recalled, “but gained the ability to think laterally.” In March 1941 she deciphered a message, “Today’s the day minus three,” which told them that the Italian Navy was up to something.

Batey and her colleagues worked for three days and nights until she decoded “a very, very long message” detailing the Italian fleet’s proposed interception of a British supply convey en route from Egypt to Greece; it included their plan of attack, strength – cruisers, submarines – locations and times. “It was absolutely incredible that they should spell it all out,” she recalled. The message was passed to Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, giving him the intelligence he needed to intercept the Italians.

He deceived the Japanese consul in Alexandria, who was passing information to the Germans, into thinking he was having the weekend off to play golf. Then under cover of darkness he set sail with three battleships, four cruisers and an aircraft carrier. Over 27-28 March 1941, his forces staged a series of surprise attacks. The Italians lost three cruisers, two destroyers and 3,000 sailors in the Battle of Matapan, never again dared to sail close to the Royal Navy. Cunningham went to Bletchley to thank Knox’s unit, ISK (Intelligence Section Knox).

Arguably, ISK’s most important coup was to break into the Enigma cipher. MI5 and MI6 had captured and identified most of Germany’s spies in Britain and in neutral Lisbon and Madrid, and had “turned” them, using them to feed false information to Germany about the Allies’ proposed invasion of France, in an operation known as the Double-Cross System.

However, no one knew if the Germans believed the intelligence, because Enigma had proven unbreakable. This machine had many millions of settings, as it used four rotors, rather than the usual three, which rotated randomly with no predictable pattern.

Working with Knox and Margaret Rock, Batey tested out every possibility, and in December 1941 broke a message on the link between Berlin and Belgrade, making it possible to reconstruct one of the rotors. Within days, ISK had broken the Enigma – and days later Batey cracked a second Abwehr cipher machine, the GGG, which confirmed that Germany believed the Double Cross intelligence.

British agents fed a stream of false intelligence to German command, convincing it that a US Army group was forming in East Anglia and Kent. Hitler believed the main invasion force would land at Pas-de-Calais rather than in Normandy, leading him to retain two key armoured divisions there. Montgomery’s head of intelligence, Brigadier Bill Williams, later said that without the deception, the Normandy invasion could well have been a disaster.