Bletchley Park

With the emergence of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany the British government began planning for the possibility of war. MI6 began purchasing sites that might be needed for its wartime needs. In 1937, the owner of Bletchley Park, an estate that included a large Victorian country house, died. Built by the financier, Herbert Leon, in 1883, it was situated 50 miles north-west of London. "Its red-brick facade boasted neither symmetry nor beauty: it was an electric assemblage of gables, crenellations, chimney-stacks and bay windows... Tucked behind it were the usual outbuildings: stables, garages, laundry and dairy facilities, and servants' living quarters." (1)

Sir Hugh Sinclair, the head of MI6 purchased Bletchley Park for £7,500. It was the tenth site acquired by the organization and was given the name "Station X". It was decided to make it the base for the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). The head of GCCS, Alastair Denniston, realised that in order to deal effectively with the increasing amount of secretly coded messages he had to recruit a number of academics to help with their work. One of Denniston's colleagues, Josh Cooper, told Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "He (Denniston) dined at several high tables in Oxford and Cambridge and came home with promises from a number of dons to attend a territorial training course. It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of this course for the future development of GCCS. Not only had Denniston brought in scholars of the humanities of the type of many of his own permanent staff, but he had also invited mathematicians of a somewhat different type who were especially attracted by the Enigma problem." (2)

Government Code and Cypher School

Bletchley Park was selected as it was more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University and the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (3) Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry were installed at the Shoulder of Mutton Inn, in Bletchley. Milner-Barry later recalled: "Hugh and I were most comfortably looked after by an amiable landlady, Mrs Bowden. As an innkeeper, she did not seem to be unduly burdened by rationing, and we were able (among other privileges) to invite selected colleagues to supper on Sunday nights, which was a great boon." (4)

Frank Birch and Gordon Welchman were billeted in the Duncombe Arms at Great Brickhill. Another member of staff, Barbara Abernethy, later recalled that Birch was a popular figure at Bletchley Park: "He (Birch) was a great person. I knitted him a blue balaclava helmet which he wore throughout the war. He was billeted in the Duncombe Arms at Great Brickhill. They had a lot of dons there, Gordon Welchman, Patrick Wilkinson. It was full of dons all the time. All of them having such a jolly time that they called it the Drunken Arns." (5)

Layout of Bletchley Park

The top floor of the house was taken by MI6. The main body of GCCS, including its Naval, Military and Air Sections were on the ground floor. This included the office of Alastair Denniston that "looked out across a wide lawn to a pond, with attractively landscaped banks". (6) At first, the codebreakers, under the control of Alfred Dilwyn Knox, were allocated working space in "a row of chunky converted interlinked houses - just across the courtyard from the main house, near the stables". It became known as the "Cottage". (7) Knox's department consisted of ten people, including "two very brilliant" young women, Margaret Rock and Mavis Batey. (8) Mavis later recalled. "We were all thrown in the deep end. No one knew how the blessed thing worked. When I first arrived, I was told, 'We are breaking machines, have you got a pencil? And that was it. You got no explanation. I never saw an Enigma machine. Dilly Knox was able to reduce it - I won't say to a game, but a sort of linguistic puzzle. It was rather like driving a car while having no idea what goes on under the bonnet." (9) "We were looking at new traffic all the time or where the wheels or the wiring had been changed, or at other new techniques. So you had to work it all out yourself from scratch.” (10)

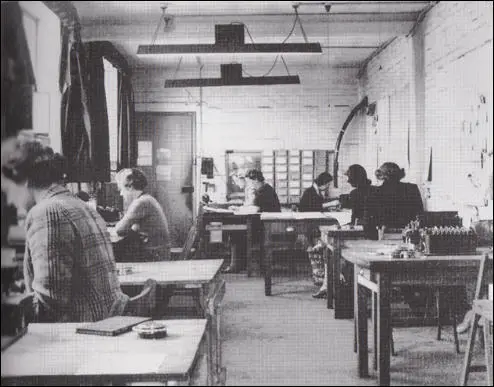

Inside the grounds of Bletchley Park they built several prefabricated wooden huts. In the intitial stages of the war the huts served different purposes: Hut 1 (Wireless Station and from March 1940, the home of the first Bombe, "Victory"); Hut 2 (recreational area that provided tea and beer); Hut 3 (translation and analysis of Army and Air Force decrypts); Hut 4 (Naval Intelligence); Hut 5 (military intelligence including Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese ciphers and German police codes) Hut 6 (cryptanalysis of Army and Air Force Enigma); Hut 7 (cryptanalysis of Japanese naval codes and intelligence) and Hut 8 (cryptanalysis of Naval Enigma). Later other huts were built to house decryption machines. These huts were like small factories. In September 1943, when Stuart Milner-Barry was promoted head of Hut 6, it comprised about 450 staff.

Francis Harry Hinsley was originally sent to Hut 3: "Hut 3 was set up like a miniature factory. At its centre was the Watch Room - in the middle a circular or horseshoe-shaped table, to one side a rectangular table. On the outer rim of the circular table sat the Watch, some half-dozen people. The man in charge, the head of the Watch or Number 1, sat in an obvious directing position at the top of the table. The watchkeepers were a mixture of civilians and serving officers, Army and RAF. At the rectangular table sat serving officers, Army and RAF, one or two of each. These were the Advisers. Behind the head of the Watch was a door communicating with a small room where the Duty Officer sat. Elsewhere in the Hut were one large room housing the Index and a number of small rooms for the various supporting parties, the back rooms. The processes to which the decrypts were submitted were, consecutively, emendation, translation, evaluation, commenting, and signal drafting. The first two were the responsibility of the Watch, the remainder of the appropriate Adviser." (11)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Oliver Lawn worked in Hut 6: "I was concerned with the codebreaking and that was it. When the code had been broken, the decoded message was passed through to the Intelligence people who used the information - or decided whether to use it. The content of messages was of no concern to me at all. I knew enough German to get an idea of what it was all about. But I had no idea of the context. And it wasn't my business. I could read the messages but they were so much in telegraphese, jargon, that they would mean nothing." (12)

Peter Twinn pointed out that it was very much a team effort: "When the codebreakers had broken the code they wouldn't sit down themselves and painstakingly decode 500 messages. I've never myself personally decoded a message from start to finish. By the time you've done the first twenty letters and it was obviously speaking perfectly sensible German, for people like me that was the end of our interest." The message was now passed on people such as Diana Russell Clarke: "The cryptographers would work out the actual settings for the machines for the day. We had these Type-X machines, like typewriters but much bigger. They had three wheels, I think on the left-hand side, all of which had different positions on them. When they got the setting, we were to set them up on our machines. We would have a piece of paper in front of us with what had come over the wireless. We would type it into the machine and hopefully what we typed would come out in German." (13)

Food at Bletchley Park

Phoebe Senyard brought in a top chef from London to look after the codebreakers and the meals, laid out on longtables in one of the downstairs rooms of the house and with full waitress service. Phoebe Senyard later recalled: "What I remember very well were the wonderful lunches with which we were served. Bowls of fruit, sherry trifles, jellies and cream were on the tables and we had chicken, ham and wonderful beefsteak puddings, etc. We certainly could not grumble about our food." (14)

Most of the other women working at Bletchley Park agreed with Senyard. Jean Valentine commented: "The food was great at Bletchley Park.... I think there was a vegetable garden just over the stone wall." Shelia Lawn recalls "One day, I went to see a film, and then, I was hungry, so I went into what was called the British Restaurant. And I thought: This isn't half as good as our canteen. I thought it was a terribly dull meal." (15)

Sarah Baring, the daughter of the Richard Henry Brinsley Norton, 6th Lord Grantley, was used to having meals of a high standard. She was less impressed with the food at Bletchley Park and describes one scene involving her friend Osla Benning : "We thought a lot about food. Night watches were especially vulnerable to rumbling tummies and usually forced us to go down to the canteen at 3 a.m., where the food was indescribably awful. It is a well-known fact that to cater for so many people is difficult, and particularly in wartime ... but our canteen outshone any sleazy restaurant in producing sludge and the smell of watery cabbage and stale fat regularly afflicted the nostrils to the point of nausea. One night I found a cooked cockroach nestling in my meat, if you can dignify it by that name, the meat not the beetle. I was about to return it to the catering manageress when my friend Osla, who had the appetite of a lioness with cubs, snatched the plate and said: 'What a waste - I'll eat it!' How she managed to eat so much - minus the insect - and stay so slim I never knew, because any leftovers on any nearby plate were gobbled up by her in a flash." (16)

Love and Marriage

There was a lot of romance at Bletchley Park. Keith Batey became involved with Mavis Lever. He felt guilty about working at the Government Code and Cypher School while so many of his contemporaries were risking their lives in open combat. "Accordingly he told his bosses that he wanted to train as a pilot, only to be informed that no one who knew that the British were breaking Enigma could be allowed to fly in the RAF, the risk being that he might be shot down and captured. Batey then suggested that he join the Fleet Air Arm, flying over the sea in defence of British ships, arguing that he would be either killed or picked up by his own side. Worn down by his persistence, his superiors reluctantly agreed." Keith married Mavis in November, 1942, shortly before he left for Canada for the Fleet Air Arm advanced flying course. (17)

Oliver Lawn fell in love with Shelia MacKenzie, another codebreaker at GCCS. Oliver later recalled that several other codebreakers married while working at Bletchley Park, including Robert Roseveare and Dennis Babbage: "There was quite a bit of romance. There were several in Hut 6 who married while they were at Bletchley. There were the Bateys, of course... The other couple I recollect was Bob Roseveare and Ione Jay. He was a mathematician, straight from school. He hadn't even gone to university. Very brilliant chap from Marlborough. He married Ione Jay, who was one of the girls in Hut 6. Then there was Dennis Babbage, who was a don similar to Gordon Welchman. Same sort of age. Babbage married while he was there." (18) Shelia and Oliver married in May 1948. (19)

Primary Sources

(1) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six Story (1982)

In the planning for the wartime Bletchley Park, Denniston's principal helpers, in Robin's recollection, were Josh Cooper, Nigel de Grey, John Tiltman, Admiral Sinclair's sister, and Sir Stuart Menzies. Edward Travis, whose later performance as successor to Alastair Denniston at Bletchley Park was so significant, must have been involved, but he was not one of the "family" team that dated back so many years. Robin believes that, before joining GCCS, Travis was involved in encipherment rather than codebreaking.

As preparatory work was being done, Denniston visited the site frequently, and made plans for construction of the numerous huts that would be needed in the anticipated wartime expansion of GCCS activities. When war actually came, these wooden huts were constructed with amazing speed by a local building contractor, Captain Hubert Faulkner, who was also a keen horseman and would often appear on site in riding clothes.

The word "hut" has many meanings, so I had better explain that the Bletchley huts were single-story wooden structures of various shapes and sizes. Hut 6 was about 30 feet wide and 60 feet long. The inside walls and partitions were of plaster board. From a door at one end a central passage, with three small rooms on either side, led to two large rooms at the far end. There were no toilets; staff had to go to another building. The furniture consisted mostly of wooden trestle tables and wooden folding chairs, and the partitions were moved around in response to changing needs.

The final move of the GCCS organization to Bletchley was made in August 1939, only a few weeks before war was declared. As security cover the expedition, involving perhaps fifty people, was officially termed "Captain Ridley's Hunting Party," Captain Ridley being the man in charge of general administration. The name of the organization was changed from GCCS to "Government Communications Headquarters" or GCHQ.

The perimeter of the Bletchley Park grounds was wired, and guarded by the RAF regiment, whose NCOs warned the men that if they didn't look lively they would be sent "inside the Park," suggesting that it was now a kind of lunatic asylum.

Denniston was to remain in command until around June 1940, when hospitalization for a stone in his bladder forced him to undertake less exacting duties. After his recovery he returned to Bletchley for a time before moving to London in 1941 to work on diplomatic traffic. Travis, who had been head of the Naval Section of GCCS and second in command to Denniston, took his place and ran Bletchley Park for the rest of the war. In recognition of his achievements he became Sir Edward Travis in 1942.

In spite of his hospitalization, Denniston, on his own initiative, flew to America in 1941, made contact with leaders of the cryptological organizations, and laid the foundations for later cooperation. He established a close personal relationship with the great American cryptologist William Friedman, who visited him in England later. The air flights were dangerous. On Denniston's return journey a plane just ahead of his and one just behind were both shot down.

(2) Roger Marsh, Shelia and Oliver Lawn (31st August 2005)

Oliver and Sheila Lawn both worked at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the very secret wartime code breaking establishment. It was called the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). All the work done at Bletchley Park remained Top Secret for some 30 years after the war, and only then were Oliver and Sheila able to talk about their work there.

Oliver Lawn was recruited for Bletchley Park by Gordon Welchman in July 1940. He had just completed a Mathematics Degree at Jesus College, Cambridge, and had expected then to be called up into the Army, as many of his contemporaries were being. Gordon Welchman, a Cambridge Mathematics Don, had been recruited for Bletchley at the beginning of the War in September 1939, along with other Oxford and Cambridge Dons, who included Alan Turing. In July 1940 Welchman was recruiting other Mathematicians, and Oliver was one of these.

He joined a team with Welchman in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, which was concerned with breaking the Enigma Codes used by the German Army and Air Force. (The Enigma Codes used by the German Navy were different, and were broken by a quite different group of people, in Hut 5.) He remained in Hut 6 for 5 years, until September 1945.

The methods mostly used for breaking these Enigma Codes were by guessing "cribs" - that is, guessing what some part of an encoded message actually said, in German. This was of course only possible for "routine" messages such as daily weather reports or forecasts, which often began, or ended with a standard phrase, or a record of the time of sending (e.g. "Wettervorhersage" or "nullsechsnullnull" "0600" hours). By aligning such phrases with the encoded text which was received over the radio in Morse code, pairs of text letters and encoded letters were thrown up, and these were grouped into "menus" looking rather like diagrams of Euclidean Geometry. The menus were then tested by large machines called "Bombes", seeking the correct setting of the Enigma machine at which the message had been encoded - the daily "key". When this "key" had been found, all the messages on that key, and on that day, could be decoded. Keys changed daily at midnight, and each day's key had to be separately discovered. There were separate daily keys for different parts of the German Services. The total number of possible Keys was 150 million million million.

(3) Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (2002)

Dilly himself always slept in the office, going back to Courn's Wood once a week. His driving was worse than ever. His mind was totally elsewhere. Fortunately he drove slowly. "It's amazing how people smile, and apologise to you, when you knock them over," he remarked.

In time the buildings inside the Park walls extended into blocks of huts and cafeterias, and by the end of the war the personnel numbered more than seven thousand, increased by observers and liaison men and important visitors in uniform. With all this Dilly had nothing to do. At first his department consisted of ten people, though these included, besides Peter Twinn, two very brilliant and sympathetic young women, Margaret Rock and Mavis Lever (now Mrs Batey). They were accommodated in a small cottage overlooking the old stable yard.

He would, however, need more ciphering clerks-not the vast numbers which eventually made the Treasury complain that "Bletchley was using up all the girls in the country," but still, a section of his own. Into this task Dilly entered with quite unexpected enthusiasm, and when the assistants arrived down from London with the files they were surprised to find him surrounded with pretty girls, all of them, for some reason, very tall, whom he had recruited for the work. The girls took from four to six months to train, though this was not undertaken by Dilly, who never trained anybody, but by a capable and understanding woman, Mrs Helen Morris. They worked on the equations in three eight-hour shifts, and when Dilly wanted to speak to them or to the punch-card operators who registered the encipherments as dots, he would limp across from the cottage, often in his grey dressing gown, indifferent to rain and snow, to tell them his new idea.

(4) Sarah Baring, The Road to Station X (2000)

We thought a lot about food. Night watches were especially vulnerable to rumbling tummies and usually forced us to go down to the canteen at 3 a.m., where the food was indescribably awful. It is a well-known fact that to cater for so many people is difficult, and particularly in wartime ... but our canteen outshone any sleazy restaurant in producing sludge and the smell of watery cabbage and stale fat regularly afflicted the nostrils to the point of nausea.

One night I found a cooked cockroach nestling in my meat, if you can dignify it by that name, the meat not the beetle. I was about to return it to the catering manageress when my friend Osla, who had the appetite of a lioness with cubs, snatched the plate and said: `What a waste - I'll eat it!' How she managed to eat so much - minus the insect - and stay so slim I never knew, because any leftovers on any nearby plate were gobbled up by her in a flash.