Francis Harry Hinsley

Francis Harry Hinsley, the son of Thomas Henry Hinsley and his wife, Emma Adey, was born in Walsall on 26th November, 1918. His father was a wagoner who drove a horse and cart between the local ironworks and the railway station. After attending the local elementary school he went to Queen Mary's Grammar School. (1)

In 1937 won a scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge, to read history. A talented student he found himself interviewed by Alastair Denniston, the head of of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) in July 1939. During his interview Denniston went through his CV, noting that he was good at sifting through old documents such as the Domesday Book. Hinsley said the kind of questions they asked me were: "You've travelled a bit, we understand. You've done quite well in your Tripos. What do you think of government service? Would you rather have that than be conscripted? Does it appeal to you?" (2) Hinsley later discovered that his name had been suggested by his history tutor, Hugh Gatty. (3) Hinsley commented: "Denniston... recruited the wartime staff from the universities with visits there in 1937 and 1938 (also 1939 when he recruited me and 20 other undergraduates within two months of the outbreak of war)." (4)

Francis Harry Hinsley in GCCS

In the summer of 1939 Hinsley spent his vacation in Nazi Germany. His girlfriend lived in Koblenz and because of the political situation, Hinsley was ordered to report to the local police station each day. On 23rd August Adolf Hitler signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. The authorities now considered war more unlikely and the police told Hinsley that he no longer needed to visit the station every day and that they would get in touch with him if any problems came up. A week later, a German policeman advised the parents of his girlfriend, "Get him out of the country by tomorrow at the latest." Hinsley immediately left and was able to cross the French border before it closed. (5)

As arranged by Alastair Denniston, Hinsley reported to Bletchley Park on the outbreak of the Second World War, that took place a few days after arriving in England. His biographer, Richard Langhorne, has pointed out: "Congregated there was a group of young, highly accomplished men and women, living a completely secret life in conditions somewhat resembling a physically uncomfortable university senior common room." (6) At first Hinsley worked under Phoebe Senyard. She later described him as "a slight, bespectacled young man with wavy hair" with a outstanding intellect. She later recalled: "I can remember quite well showing Harry some of the sorting and how delighted he seemed when he began to recognise the different types of signals... If I was in difficulty, I knew I could go to Harry. It was a pleasure because he was always interested in everything and took great pains to find out what it was and why. Those were very enjoyable days indeed. we were all very happy and cheerful, working in close cooperation with each other." (7)

Francis Harry Hinsley was originally sent to Hut 3: "Hut 3 was set up like a miniature factory. At its centre was the Watch Room - in the middle a circular or horseshoe-shaped table, to one side a rectangular table. On the outer rim of the circular table sat the Watch, some half-dozen people. The man in charge, the head of the Watch or Number 1, sat in an obvious directing position at the top of the table. The watchkeepers were a mixture of civilians and serving officers, Army and RAF. At the rectangular table sat serving officers, Army and RAF, one or two of each. These were the Advisers. Behind the head of the Watch was a door communicating with a small room where the Duty Officer sat. Elsewhere in the Hut were one large room housing the Index and a number of small rooms for the various supporting parties, the back rooms. The processes to which the decrypts were submitted were, consecutively, emendation, translation, evaluation, commenting, and signal drafting. The first two were the responsibility of the Watch, the remainder of the appropriate Adviser." (8)

Frank Birch was head of the German section in Hut 4. He told Hinsley that they were trying to read intercepted German naval messages. "The code used by the Germans had not yet been broken. That being the case, Hinsley was to do his best to find out as much as he could from the information they did have about these messages. It was quickly apparent that there was not much evidence to go on. There was the date of the messages, their time of origin and their time of interception, and the radio frequency used by the German morse code operators. Sometimes Hinsley would be told where the messages came from, information which had been gleaned using the Royal Navy's direction finding service." Hinsley became involved with what became known as "traffic analysis". This was defined as "looking at all the evidence relating to enciphered messages which could not be read, and reaching a conclusion on what the enemy was doing." (9)

Admiralty's Operational Intelligence Centre

After Norway was invaded in April 1940, Hinsley was allowed direct contact with the Admiralty's Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC). The following month Hinsley noticed that German naval messages were being sent on frequencies which had never been used before. Hinsley came to the conclusion that the Germans were about to move some of their ships from the Baltic Sea to the Skagerrak, the narrow stretch of sea separating Denmark and Norway. He passed on this information to OIC. However, they failed to notice the significance of this information. Unknown, to the British, the Germans had broken the Royal Navy's codes and they were using this information to track HMS Glorious, the aircraft carrier, on the way to Norway.

At about 5.30 p.m. on 8th June, the German battleship, Scharnhorst opened fire, "hitting Glorious with salvo after salvo of shells shot out of her 11-inch guns, until the British aircraft carrier was just a blazing inferno full of mutilated corpses". (10) The two escorting destroyers, were also sunk, leaving behind just three survivors. The total killed or missing was 1,207 from Glorious, 160 from Acasta and 152 from Ardent, a total of 1,519. (11)

Shortly after the sinking of Glorious, Hinsley was asked to go up to the Admiralty's Operational Intelligence Centre in London, to explain how his traffic analysis worked. The meeting was attended by Rear Admiral Jock Clayton and Commander Norman Denning: "The OIC, which operated in the basement of the Citadel, had its own intelligence team, and Clayton wanted them to be well briefed, so that everyone could react quickly next time Hinsley rang them up. Clayton and Denning must have been surprised when Hinsley was ushered into their office. For standing before them was a man who was young enough to be one of Clayton's grandchildren. Hinsley was acutely aware that his long hair and casual clothing, which no one thought twice about in the laid back dons' common room atmosphere at Bletchley Park, was out of place beside all the spotless naval uniforms and suits worn at the Admiralty. Perhaps that was one reason why Hinsley found that his ideas did not receive a good reception from the junior officers he was supposed to be teaching. Another reason was that traffic analysis was not as easy as it sounded. Not everyone could cope with hours of searching through incomprehensible enciphered messages in the often vain hope of finding a ray of light hidden amongst the sea of paper. Hinsley on the other hand was well prepared for the job he had been given. His medieval history course at Cambridge had required him to look for the minuscule changes made to the charters he was analysing." (12)

Francis Harry Hinsley still had difficulty in communicating important information to the OIC. His colleague, Alec Dakin, wrote about this problem to Frank Birch was head of the German section in Hut 4. Dakin suggested that the military establishment was prejudiced against Hinsley's working-class background: "In their present state of ignorance, these people are not able to interpret and pass on any information they receive from Hinsley or the watch. That they should be jealous of his success is understandable, and that they should dislike him personally is a small matter, but that they should be obstructive is ruinous. (13)

Two days later Hinsley also wrote to Birch: "The only conclusion is that they not only duplicate our work and other people's work, but duplicate it in so aimless and inefficient a manner, that all their time is taken up in groping at the truth, and putting as much of it as is obvious to all on card indexes. If they duplicated in the right spirit, and with some purpose, they would be able to answer questions properly, and also possibly to contribute to general advancement... One reason that prevented them from doing this, appeared to be a competitive spirit, which instead of being of a healthy type, is obviously personal and couched itself in a show of independence and an air of obstruction. It appeared to be based on personal opposition to Bletchley Park. It was increased by the fact that the presence of one person from BP appeared to them to remove all their raison d'etre. They felt themselves cut out... Apart from the above, I suspect that another reason for their inadequacy is incapacity, pure and simple. They know facts... But they seem to have no general grasp of these facts in association. They lack imagination. They cannot utilise the knowledge they so busily compile." (14)

According to his biographer, Richard Langhorne, the OIC eventually began taking his advice: "His powers as an interpreter of decrypts were unrivalled and were based on an ability to sense that something unusual was afoot from the tiniest clues. Hinsley became the leading expert on the decryption and analysis of German wireless traffic, and, particularly after the capture of German Enigma code machines and materials, which allowed their settings to be broken, played a vital role in supplying the Admiralty with crucial intelligence analysis derived from Admiral Doenitz's signals." (15) His work was vitally important in the Battle of Atlantic. As a result of the work done at Bletchley Park, nearly a hundred U-boats were sunk in the first five months of 1943. On 23rd May, after hearing of the loss of the forty-seventh U-boat that month, Karl Dönitz ordered the wolf packs to be withdrawn from the Atlantic. (16)

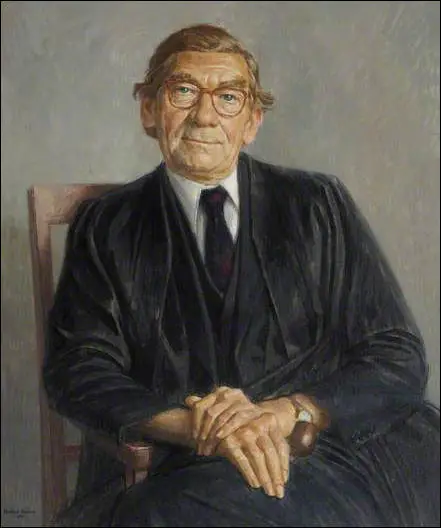

Francis Harry Hinsley at St John's College

At the end of the Second World War, Hinsley returned to St John's College, Cambridge, where he taught history. He also published Power and the Pursuit of Peace (1963) and Sovereignty (1966). In 1969 he was appointed as professor of the history of international relations in 1969. "He was a great teacher, an important writer, and a notably competent administrator. Countless generations of undergraduate historians at Cambridge remembered the extraordinarily vivid way in which he taught them, but the research school in the history of international relations that he established in the 1960s and 1970s was one of his greatest achievements." (17)

Frederick Winterbotham, who had worked at Government Code and Cypher School during the war, approached the government and asked for permission to reveal the secrets of the work done at Bletchley Park. The intelligence services reluctantly agreed and Winterbotham's book, The Ultra Secret, was published in 1974. Permission was now given to Francis Harry Hinsley, to publish his five volume British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979-1990). He also published Codebreakers: the Inside Story of Bletchley Park (1993), which served to add the flesh and blood excluded from the official account.

One of his students later recalled: "Hinsley was a strikingly rich character, almost a phenomenon of nature, in contrast to his bespectacled and physically slight appearance.... For many of his students, it was Hinsley's analytical skill so honed at Bletchley Park that affected them most. Whether in private - and always unstinting - discussion or at the famous weekly seminar he ran for all interested parties at every level, from behind a thick pall of pipe smoke, he reacted to the wider implications of what had been discovered or reassessed; and he would comment rapidly, almost electrically, on the true significance of what he had just heard or read. He never forgot any student he had taught or been tutor to, and his students never forgot their exposure to how he thought about things and the often striking language he used to describe what he thought." (18)

Sir Francis Harry Hinsley died of lung cancer at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, on 16th February 1998.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Harry Hinsley, British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume One (1979-1990)

By 1937 it was established that... the German Army, the German Navy and probably the Air Force, together with other state organizations like the railways and the SS used, for all except their tactical communications, different versions of the same cypher system - the Enigma machine which had been put on the market in the 1920s but which the Germans had rendered more secure by progressive modifications.

(2) Michael Smith, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998)

Harry Hinsley had arrived at Bletchley in late 1939 and was immediately put in Phoebe Senyard's care. Unlike many of the dons, he did not have a privileged background. Hinsley was a grammar school boy from Walsall, in the Black Country. His father was a wagoner who drove a horse and cart between the local ironworks and the railway station. A slight, bespectacled young man with wavy hair, who had won a scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge, he was an immediate hit with Senyard.

(3) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

The Security Officer on the gate used his telephone and summoned up a WAAF officer. She led me across a noble lawn, with on the left a Tudorbethan mansion, on the right a large lake; in front a small office. (It should be noted that the hut numbers not only designated the huts themselves but were also used as cover-names for the work going on in them. When, towards the end of the war, the Hut 3 work was transferred to a brick building, it was still called Hut 3.)

In my initiation stress was laid on the value of work going out from Hut 3. It was "the heart of the matter" and of immense importance. The Enigma had been mastered. The process up to the production of raw decrypts was carried out in Hut 6 next door. It was the task of Hut 3 to evaluate them and put the intelligence they contained into a form suitable for passing to the competent authorities, be they Ministries or Commands.

(4) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004)

Frank Birch was head of the German section in Hut 4. He told Hinsley that they were trying to read intercepted German naval messages. The code used by the Germans had not yet been broken. That being the case, Hinsley was to do his best to find out as much as he could from the information they did have about these messages. It was quickly apparent that there was not much evidence to go on. There was the date of the messages, their time of origin and their time of interception, and the radio frequency used by the German morse code operators. Sometimes Hinsley would be told where the messages came from, information which had been gleaned using the Royal Navy's direction finding service.

Using all of the available information, Hinsley worked out that the German Navy only had two radio networks: one for the Baltic and one for outside the Baltic. There did not appear to be a separate network for surface ships and a different network for U-boats. Hinsley could only hope that would change once the Germans began conducting major naval operations. For the moment, he was stuck in a dead end job with no opportunity to make his mark.

(5) Phoebe Senyard, quoted by Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998)

I can remember quite well showing Harry some of the sorting and how delighted he seemed when he began to recognise the different types of signals. He joined up with Miss Bostock working on frequencies and callsigns. I then had to pass to Harry any strange, new or unknown signals. If I was in difficulty, I knew I could go to Harry. It was a pleasure because he was always interested in everything and took great pains to find out what it was and why. Those were very enjoyable days indeed. We were all very happy and cheerful, working in close cooperation with each other.

(6) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

It remained a loose collection of groups rather than forming a single, tidy organisation... Professors, lecturers and undergraduates, chessmasters and experts from the principal museums, barristers and antiquarian booksellers, some of them in uniform and some civilians on the books of the Foreign Office or the Service ministries - such for the most part were the individuals who inaugurated and manned the various cells which sprang up within or alongside the original sections. They contributed by their variety and individuality to the lack of uniformity. There is also no doubt that they thrived on it, as they did on the absence at GC&CS of any emphasis on rank or insistence on hierarchy.

(7) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

Hut 3 was set up like a miniature factory. At its centre was the Watch Room - in the middle a circular or horseshoe-shaped table, to one side a rectangular table. On the outer rim of the circular table sat the Watch, some half-dozen people. The man in charge, the head of the Watch or Number 1, sat in an obvious directing position at the top of the table. The watchkeepers were a mixture of civilians and serving officers, Army and RAF. At the rectangular table sat serving officers, Army and RAF, one or two of each. These were the Advisers. Behind the head of the Watch was a door communicating with a small room where the Duty Officer sat. Elsewhere in the Hut were one large room housing the Index and a number of small rooms for the various supporting parties, the back rooms.

The processes to which the decrypts were submitted were, consecutively, emendation, translation, evaluation, commenting, and signal drafting. The first two were the responsibility of the Watch, the remainder of the appropriate Adviser.

(8) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004)

Shortly after the sinking of Glorious, Hinsley was asked to go up to the Citadel in London, the building in the Mall where the OIC was situated, to explain how his traffic analysis worked. The OIC, which operated in the basement of the Citadel, had its own intelligence team, and Clayton wanted them to be well briefed, so that everyone could react quickly next time Hinsley rang them up. Clayton and Denning must have been surprised when Hinsley was ushered into their office. For standing before them was a man who was young enough to be one of Clayton's grandchildren. Hinsley was acutely aware that his long hair and casual clothing, which no one thought twice about in the laid back dons' common room atmosphere at Bletchley Park, was out of place beside all the spotless naval uniforms and suits worn at the Admiralty. Perhaps that was one reason why Hinsley found that his ideas did not receive a good reception from the junior officers he was supposed to be teaching.

Another reason was that traffic analysis was not as easy as it sounded. Not everyone could cope with hours of searching through incomprehensible enciphered messages in the often vain hope of finding a ray of light hidden amongst the sea of paper. Hinsley on the other hand was well prepared for the job he had been given. His medieval history course at Cambridge had required him to look for the minuscule changes made to the charters he was analysing. His upbringing also helped. He had been brought up to make the most of the little which was available to him. Money had always been in short supply when he was young. His father was an occasional labourer, who spent most of the 1930s out of work. His mother worked as a cleaner, providing just enough to keep the Hinsley family clothed and fed. He was proud of the fact that when he went to Germany in 1939, he managed to survive on a meagre budget of just £5 for the entire summer.

(9) Alec Dakin, letter to Frank Birch (21st October 1940)

ID8G, its relations with us and its attitude to our staff. Here the prime test is Hinsley and his dope; practically we stand or fall with him. I believe that anyone who reads one or two of Hinsley's best Y serials, (especially the Glorious one, of course), and bears in mind that A.C.N.S. has been letting him send signals to the fleets, must conclude that there is something in it, that Hinsley's linkages do give him "indications" of future activity, which examination of the bulk of the traffic do not give. But ID8G, not least the day and night watchkeepers, who are the people concerned, seem never to have studied a Y... and if one discusses the validity of the linkage approach with them one has to start at the very first principle, and say that a non-linked message may be dummy, or weather, or "I have anchored because of fog", or even 'The captain's wife has had twins', whereas a linked message is pretty certain to mean something. In their present state of ignorance, these people are not able to interpret and pass on any information they receive from Hinsley or the watch. That they should be jealous of his success is understandable, and that they should dislike him personally is a small matter, but that they should be obstructive is ruinous.

(10) Francis Harry Hinsley, letter to Frank Birch (23rd October 1940)

The only conclusion is that they not only duplicate our work and other people's work, but duplicate it in so aimless and inefficient a manner, that all their time is taken up in groping at the truth, and putting as much of it as is obvious to all on card indexes. If they duplicated in the right spirit, and with some purpose, they would be able to answer questions properly, and also possibly to contribute to general advancement... One reason that prevented them from doing this, appeared to be a competitive spirit, which instead of being of a healthy type, is obviously personal and couched itself in a show of independence and an air of obstruction. It appeared to be based on personal opposition to Bletchley Park. It was increased by the fact that the presence of one person from BP appeared to them to remove all their raison d'etre. They felt themselves cut out... Apart from the above, I suspect that another reason for their inadequacy is incapacity, pure and simple. They know facts... But they seem to have no general grasp of these facts in association. They lack imagination. They cannot utilise the knowledge they so busily compile.

References

(1) Richard Langhorne, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 23

(3) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) pages 53-54

(4) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Robin Denniston, the author of Thirty Secret Years (2007) page 24

(5) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) page 53

(6) Richard Langhorne, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(7) Phoebe Senyard, quoted by Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 55

(8) Francis Harry Hinsley, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007) page 55

(9) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) pages 55 and 138

(10) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) page 140

(11) John Winton, Carrier Glorious: The Life and Death of an Aircraft Carrier (1999) page 200

(12) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) page 139

(13) Alec Dakin, letter to Frank Birch (21st October 1940)

(14) Francis Harry Hinsley, letter to Frank Birch (23rd October 1940)

(15) Richard Langhorne, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(16) Michael Smith, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 117

(17) Richard Langhorne, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)