Bobby Baker

Robert (Bobby) Gene Baker, the son of Ernest Baker and the former Mary Elizabeth Norman, was born in the village of Eastley, in South Carolina, on 12th November, 1929. He was named after two sports figures, the golfer Bobby Jones and the boxer Gene Tunney. (1)

Baker later recalled: "I was born the first of eight children, the son of a millhand father and a mother who had clerked in Rich's Department Store in Atlanta before becoming an eighteen-year-old bride.... He was forced to leave high school in his senior year and go to work as a millhand after his own father had been fired from the mills for trying to organize a labour union among the workers." (2)

At the age of eight he found work as a cleanup boy at the Rexall Drugstore in Pickens. He rose through the ranks to delivery boy to soda jerk to become an "unofficial" store manager. He later wrote that he developed an aptitude for sizing up the wants and desires of some of the town’s leading citizens: "As a delivery boy, I witnessed secret drinkers and occasionally found a strange man in another man’s house. Very early I concluded that things are not always what they seem." (3)

Page Boy in Washington

In 1942, Burnet R. Maybank, a senator for South Carolina, offered Baker the possibility of becoming a page boy in Washington. "Far from being excited at the prospect of Washington, I shrank from it. I did not know what a page boy was and found little condolence in the dictionary: a page boy seemed to be a mere messenger; I preferred to remain among my friends - where I had status as a cheerleader and flashy soda jerk - rather than to walk among strangers in a job of no particular merit." (4)

Baker arrived in Washington on 1st January, 1943. He was only 14 years-old and during the first few weeks he was unhappy and homesick. He also attended the Page Senate School and later studied for a law degree from American University. (5) Baker gradually adapted to his new surroundings and became a popular member of the team. "I realized early on that the key to being efficient and well liked in the Senate was learning to anticipate what each senator might require... It was not long until many senators asked for me by name." (6)

By the age of twenty, Baker developed a reputation for being very well-informed and became known as the Senate's "chief staff tactician on legislative business". Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican Party whip, told him "Mr. Baker, you are the best vote-counter in the history of the Senate" and that this made him a very powerful political figure. Baker added: "Dirksen became a wonderful friend... I have great admiration for him…. He never saw a $100 bill he didn’t like." (7)

Bobby Baker and Lyndon B. Johnson

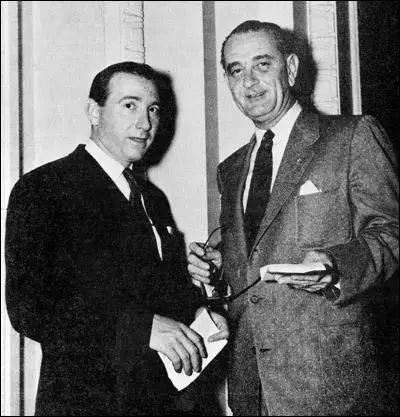

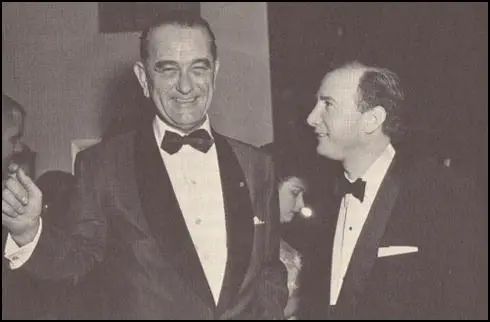

In December, 1949, Lyndon B. Johnson, the young senator from Texas, telephoned him: "Mr Baker, I understand you know where the bodies are buried in the Senate. I'd appreciate it if you'd come to my office." When he arrived the new senator asked Baker: "I want to know who's the power over there, how you get things done, the best committees, the works." According to Ronnie Dugger, he spent the next two hours interrogating Baker. (8)

Baker later recalled: "No senator ever had approached me with such a display of determination to learn, to achieve, to attain, to belong, to get ahead. He was coming into the Senate with his neck bowed, running full tilt, impatient to reach some distant goal I then could not even imagine. It was, as I came to know, wholly characteristic of Lyndon Johnson and close to a typical performance. Politics simply consumed the man." (9)

It was Baker's job to compile background information on other politicians: “They let their hair down when they’ve had a few drinks, tell you their likes and dislikes, and you file it away. You find out who likes to take trips around the world, and then you try to repay those who voted against their conscience to help you. Senator Johnson was very adept at taking care of senators and their wishes, and the bills that they wanted.” (10)

The two men became very close and when Johnson became Senate majority leader in 1955, he made Baker secretary to the majority. "Mr. Baker proved especially adept at the math of the Senate - he would usually know precisely how many votes a piece of legislation could garner at any given moment, a valuable skill in the horse-trading world of Washington politics." (11)

Business Associates

In the early 1950s Baker worked closely with Fred Black. He also became involved in helping the Intercontinental Hotels Corporation to establish casinos in the Dominican Republic. Baker arranged for Ed Levinson, an associate of Meyer Lansky and Sam Giancana, to become involved in this deal. When the first of these casinos were opened in 1955, Baker and Johnson were invited as official guests. "While working for Johnson, Baker became the epitome of Washington wheeler-dealer sleaze. Repeatedly, he fronted for syndicate gamblers Cliff Jones and Ed Levinson in investments that earned super profits for himself and another military-industrial lobbyist, his friend Fred Black Jr. In exchange he intervened to help Jones and Levinson obtain casino contracts with the Intercontinental Hotel system." (12)

Bobby Baker along with Walter Jenkins, Edward A. Clark and Clifford Carter were Johnson's "bagman" who he would rely "upon to obfuscate his relationship with criminals". These men dealt with Irving Davidson, Clint Murchison, James Hoffa and Carlos Marcello. Davidson was deeply involved in Baker's scams. Murchison paid Baker to secure a government contract for a meat-packing company he owned in Haiti, while he worked on defending Jimmy Hoffa." (13)

1960 Presidential Election

In 1960 Lyndon B. Johnson was selected by John F. Kennedy as his running-mate. This upset Senator Robert Kerr who wanted Johnson to remain as majority leader of the Senate: "Kerr literally was livid. There were angry red splotches on his face. He glared at me, at LBJ, and at Lady Bird. 'Get me my .38,' he yelled. 'I'm gonna kill every damn one of you. I can't believe that my three best friends would betray me.' Senator Kerr did not seem to be joking. As I attempted to calm him he kept shouting that we'd combined to ruin the Senate, ruin ourselves, and ruin him personally. Lyndon Johnson, no slouch as a tantrum tosser himself, had little stomach for dealing with fits thrown by others; he motioned me to take Senator Kerr into the bathroom and mumbled something about explaining things to him."

In the bathroom Baker explained the situation "If he's elected vice-president he'll be an excellent conduit between the White House and the Hill. He'll still be around to consult." He added "I knew that LBJ had arranged a Texas law permitting him to run for reelection to the Senate at the same time he sought any national office; he later, indeed, would be reelected senator from Texas and vice-president on the same day and on the same ballot." Baker went on to argue: "So what in the world's he got to lose? I think it's a tremendous opportunity. It's a lot of pluses and I don't see the minuses." (14)

In 1960 Johnson's was elected as vice president under Kennedy. Baker remained as Johnson's secretary and political adviser. He continued to do business with Ed Levinson, Sam Giancana and Benny Siegelbaum (an associate of Jimmy Hoffa) in the Dominican Republic. Baker argued that Dominican Republic could be a Mafia replacement for Cuba. However, these plans came to an end when the military dictator, Rafael Trujillo, was murdered on the orders of the CIA. President Kennedy now gave his support to Juan Bosch when he was elected to office in December, 1962. (15)

Baker had already arranged another source of income. In 1962 he had had established the Serve-U-Corporation with his friend, Fred Black, and mobsters Ed Levinson and Benny Sigelbaum. The company was to provide vending machines for companies working on federally granted programs. The machines were manufactured by a company secretly owned by Sam Giancana and other mobsters based in Chicago. (16)

The president of Serve-U-Corporation was Eugene A. Hancock, who was a business partner of Grant Stockdale and George Smathers at Automatic Vending Services. Questions were asked about Stockdale's business involvement with Baker. In an interview he insisted he was "absolutely not" a stockholder in Serve-U-Corporation. He also pointed out that he had disposed of his holdings in Automatic Vending Services, more than a year earlier. However, under pressure from President Kennedy, he resigned as Ambassador to Ireland in July, 1962. (17)

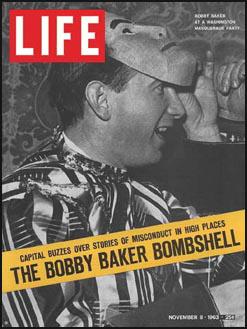

Rumours began circulating that Baker was involved in corrupt activities. Although officially his only income was that of Secretary to the Majority in the Senate, he was clearly a very rich man. According to The New York Times: "During his time as a public servant, Mr. Baker was also pursing various business ventures: real estate, hotels, a vending machine company. In 1963, an associate in the vending business brought a civil suit against him, and the resulting publicity soon drew the scrutiny of the Justice Department and other investigative bodies. They wondered, among other things, how Mr. Baker could have become a millionaire when his government job paid less than $20,000 a year." (18)

Ellen Rometsch

In 1961 Baker established the Quorum Club. This was a private club in the Carroll Arms Hotel on Capitol Hill. "Its membership was comprised of senators, congressmen, lobbyists, Capitol Hill staffers, and other well-connecteds who wanted to enjoy their drinks, meals, poker games, and shared secrets in private accommodations". (19) Time Magazine reported: "Among the 197 members are many lobbyists and several governmental figures, including Democratic Senators Frank Church of Idaho, Daniel Brewster of Maryland, J. Howard Edmondson of Oklahoma and Harrison Williams of New Jersey. Among Republican members are two Congressmen, Montana's James Battin and Ohio's William Ayres." (20)

Ellen Rometsch joined the Quorum Club as a waitress. "She was a Washington party girl... she was stunningly attractive, an Elizabeth Taylor look-alike... She was born in 1936 in Kleinitz, Germany, a village that became part of East Germany after World War II... She fled with her family to West Germany in 1955 and, after a failed first marriage, moved in 1961 to the United States with her second husband, a sergeant in the West German air force who was assigned to the German Embassy in Washington." (21)

Members of the club soon began paying attention to Rometsch. "Clad in a scanty black skin-tight uniform, with black mesh hose, the West German beauty compared favourably with the nude painting which adorned the plush back bar. Whether it was the Quorum Club outfit or her natural endowments, or both, Elly began moving in a real swinging set." Bobby Baker seemed very interested in her and took her on holiday to New Orleans." (22)

One of Kennedy's friends, Bill Thompson, discovered Rometsch at the Quorum Club and asked Baker about her. Baker told him, "She was a very lovely, beautiful party girl... who always wore beautiful clothes. She had good manners, and she was very accommodating. I must have had fifty friends who went with her, and not one of them ever complained. She was a real joy to be with." (23)

Baker admitted that he introduced Rometsch "to Jack Kennedy at his request". According to Baker he often arranged for women to meet politicians. This included Kennedy who "seemed to to relish sharing the details of his conquest; though he was not without charm or wit in relating the clinical complexities, he came off as something of the boyish braggart." Baker denied he was a pimp: "I'm not saying that nobody ever left the Quorum Club to share a bed with a temporary partner, or that certain schemes were not hatched there, but I could make the same statement of Duke Zeibert's, The Rotunda." (24)

Baker told Lyndon B. Johnson about Kennedy's relationship with Rometsch. He in turn informed his friend, J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In July 1963, FBI agents questioned Rometsch about her past. They came to the conclusion that she was probably a Soviet spy. Hoover actually leaked information to the journalist, Courtney Evans, that Rometsch worked for Walter Ulbricht, the communist leader of East Germany.

Hoover now leaked the information to Clark Mollenhoff. On 26th October, 1963, he wrote an article in the Des Moines Register claiming that the FBI had "established that the beautiful brunette had been attending parties with congressional leaders and some prominent New Frontiersmen from the executive branch of Government... The possibility that her activity might be connected with espionage was of some concern, because of the high rank of her male companions". Mollenhoff claimed that John Williams "had obtained an account" of Rometsch's activity and planned to pass this information to the Senate Rules Committee, the body investigating Baker. (25)

The following day Robert Kennedy sent La Verne Duffy to West Germany to meet Ellen Rometsch. In exchange for a great deal of money she agreed to sign a statement formally "denying intimacies with important people." Kennedy now contacted Hoover and asked him to persuade the Senate leadership that the Senate Rules Committee investigation of this story was "contrary to the national interest". He also warned on 28th October that other leading members of Congress would be drawn into this scandal and so was "contrary to the interests of Congress, too". Hoover had a meeting with Mike Mansfield, the Democratic leader of the Senate and Everett Dirksen, the Republican counterpart. What was said at this meeting has never been released. However, as a result of the meeting that took place in Mansfield's home the Senate Rules Committee decided not to look into the Rometsch scandal. (26)

It is claimed that Baker had tapes and photographs of JFK's sexual activities involving Rometsch. He also knew about JFK's earlier relationships with Maria Novotny and Suzy Chang, both of whom were from Communist countries and had been named as part of the spy ring that had trapped John Profumo, the British Secretary of State for War. When Robert Kennedy was told about this information, he ordered her to be deported. "Hoover cooperated with RFK in this instance - not to help protect the president - to protect the vice president, who he feared could be connected to a Baker prostitute if the ongoing investigations led to a public disclosures." (27)

Nancy Carole Tyler

Bobby Baker had also started a relationship with his secretary, Nancy Carole Tyler, She lived with Mary Jo Kopechne, who worked for George Smathers. "What started as a harmless affair eventually evolved into a romance, and I grew to love Carole Tyler. Young and beautiful and vivacious, at once a former beauty queen and a quick mind with a flair for politics, she was not difficult to love. Though I knew the guilt of a longtime family man with a loyal wife and five children, I did nothing to discourage our romance once it began." (28)

G. R. Schreiber, the author of The Bobby Baker Affair (1964) pointed out: "Nancy Carole joined Bobby's staff with the title of telephone page for the majority, a job which paid her $5,687.56 to start. Her work was more than satisfactory and she was rewarded with a fast series of pay raises. Almost two months to the day after she joined Bobby's staff she got her first increase to $6,052.11. Four months later, in August, 1961, her salary was boosted to $6,538.19 and that October - eight months after she joined his staff Bobby promoted Nancy Carole to clerk for the secretary to the majority, a kind of administrative assistant, and raised her pay to $7,753.34. October 16, 1962... Nancy Carole's salary was boosted again, this time to $8,296.07." (29)

In November, 1962, Tyler moved into the townhouse Baker purchased. After an initial down payment of $28,800 he paid the $238 monthly payments. "Carole's place in Southwest Washington, an upper-middle-class redevelopment area of closely packed high-rises and town houses, became the center where Bobby's friends, male and female, often met. How Bobby spent his off-duty hours was more or less common knowledge on the Hill, but those were the days when Bobby was on top, when there seemed nothing unusual about his diversions and when no one thought that, as Senate practices go, there was anything there to get excited about." (30)

Time Magazine seemed to be aware of the relationship: "One subject of considerable curiosity was Carole Tyler, 24, a shapely (5 ft. 6 in., 35-26-35) Tennessee girl who won the title of 'Miss Loudon County' before she turned up in Washington in 1959. Three years later she was Baker's private secretary at $8,000 a year. Chain-smoking, martini-drinking, party-loving Carole also became a favorite in Baker's high-flying circle of acquaintances." (31)

Corruption Charges

Rumours began circulating that Baker was involved in corrupt activities. Although officially his only income was that of Secretary to the Majority in the Senate, he was clearly a very rich man. The journalist, G. R. Schreiber, asked: "How do you build a two million dollar fortune in eight years on a salary of less than $20,000? The answer is that Bobby found it easy because so many people were ready to help him." (32)

Baker was investigated by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. He later recalled: The newspapers had a number of articles, The Washington Post particularly. I had always heard stories about Bobby Baker, about all his money and free use of money.... Our first involvement in it came, I suppose, in a conversation I had with Ben Bradlee... who had some information. I can't remember exactly what it was, but they printed it in Newsweek. He asked me if we would look into it, and I said we would look into it." (33)

Robert Kennedy discovered Baker had links to Clint Murchison and several Mafia bosses. Evidence also emerged that Lyndon B. Johnson was also involved in political corruption. This included the award of a $7 billion contract for a fighter plane, the F-111, to General Dynamics, a company based in Texas. On 7th October, 1963, Bobby Baker was forced to resign his post. Soon afterwards, Fred Korth, the Navy Secretary, was also forced to resign because of the F-111 contract. (34)

Reports circulated in Washington that the White House was pushing the Baker investigation to embarrass Lyndon Johnson: "Kennedy wants to use the Baker affair to dump Lyndon from the ticket next year." (35) Robert Kennedy later denied this: There were a lot of stories that my brother and I were interested in dumping Lyndon Johnson and that I'd started the Bobby Baker case in order to give us a handle to dump Lyndon Johnson. Well, number one, there was no plan to dump Lyndon Johnson. That didn't make any sense. Number two, I hadn't gotten really involved in the Bobby Baker case until after a good number of newspaper stories had appeared about it.... There were a lot of stories then, after November 22, that the Bobby Baker case was really stimulated by me and that this was part of my plan to get something on Johnson. That wasn't correct." (36)

On 22nd November, 1963, a friend of Baker's, Don B. Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his Senate Rules Committee that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for this business. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds also had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". (37)

Reynolds' testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. "Reynolds was stunned. If President Kennedy was dead, then Lyndon Johnson, the man about whom he had been talking, was President of the United States." Reynolds told his lawyer: "Giving testimony involving the Vice President is one thing, but when it involves the President himself, that is something else. You can just forget that I ever said if you want to." (38)

As soon as Lyndon B. Johnson became president he contacted Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because "it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread." (39)

Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Don B. Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953. (40)

Joachim Joesten, an investigative journalist, wrote that there was a connection between the investigation into Bobby Baker and the assassination of John F. Kennedy: "The Baker scandal then is truly the hidden key to the assassination, or more exact, the timing of the Baker affair crystallized the more or less vague plans to eliminate Kennedy which had already been in existence the threat of complete exposure which faced Johnson in the Baker scandal provided that final impulse he was forced to give the go-ahead signal to the plotters who had long been waiting for the right opportunity." (41)

Edward Jay Epstein, later wrote an article for the Esquire Magazine where he claimed that Reynolds had given the Warren Commission information on the death of John F. Kennedy. "In January of 1964 the Warren Commission learned that Don B. Reynolds, insurance agent and close associate of Bobby Baker, had been heard to say the FBI knew that Johnson was behind the assassination. When interviewed by the FBI, he denied this. But he did recount an incident during the swearing in of Kennedy in which Bobby Baker said words to the effect that the s.o.b. would never live out his term and that he would die a violent death." (42)

Baker's mistress, Nancy Carole Tyler until she moved back to Tennessee "but after the headlines cooled off she returned to Washington to work" for Baker as his bookkeeper at the Carousel Hotel, near Ocean City, Maryland. Baker resumed his romance with Tyler: "I loved Carole, but I refused to leave my family for her. This led to stormy scenes in which she sometimes cried or threatened to commit suicide. Despite such scenes there were moments of fun and sharing." (43)

On 9th May, 1965, Nancy Carole Tyler met Robert H. Davis, and agreed to go on a sightseeing tour over the eleven-mile-long island on which the hotel had been built in his Waco biplane. (42a) Baker later recalled: "Witnesses later said that the single-engine aircraft approached the Carousel, buzzed it a few times at low altitudes, and then began to pull up sharply as it banked into a turn taking it out over the Atlantic. The aircraft failed to come out of the turn. It hit the water nose-first at high speed and sank like a stone, only a couple of hundred yards from the Carousel.... When I saw Carole's body dressed in a green pants suit I had bought her, I broke down and cried like a baby." (44)

Despite the efforts of his lawyer, Edward Bennett Williams, in 1967 Baker was found guilty of seven counts of theft, fraud and income tax evasions. This included accepting large sums in "campaign donations" intended to buy influence with various senators, but had kept the money for himself. He was sentenced to three years in federal prison but served only sixteen months. Baker commented: "Russia wouldn’t have treated me the way this country has... But I have no great resentment. No, this is a great country. It’s done a lot for me. I like to think I have done a lot for it." (45)

Baker later wrote about his experiences in his entertaining book Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978). Arthur M. Schlesinger, who reviewed the book for the New York Times, commented that "Bobby Baker’s Senate is composed of crooks, drunks and lechers, marching from bar to boudoir to bank, concerned mainly with lining their pockets and satisfying their appetites." (46)

Baker's marriage to Dorothy Comstock, a clerk for the Senate internal security subcommittee, ended in divorce. Their son Lyndon died at 16 in an automobile accident. He had four other children, 14 grandchildren; and 14 great-grandchildren. After his retirement he moved to Florida where he worked for a time for a waste management firm. Later he managed his successful real estate investments. (47)

In 2009 he was interviewed by Donald Ritchie. "His recollections - of an age when senators drank all day, indulged in sexual dalliances with secretaries and constituents, accepted thousands of dollars in bribes and still managed to pass the most important legislation of the 20th century - were collected by the Senate Historical Office... The resulting 230-page manuscript was so ribald and riveting, so salacious and sensational, that the Historical Office refrained from its usual practice of posting such interviews online." (48)

Baker claimed that Ellen Rometsch returned to the United States in 1964 and had an affair with Gerald Ford during his time on the Warren Commission where he was tasked with investigating President Kennedy’s assassination. The affair was used against him by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover who was frustrated that the Warren Commission was not sharing their findings, "So, (Hoover) had this tape where Jerry Ford was having oral sex with Ellen Rometsch. You know, his wife had a serious drug problem back then… Hoover blackmailed… Ford to tell him what they were doing." (49)

In December 2013, the German newspaper, Die Welt, attempted to interview Rometsch. "What exactly happened between her and Kennedy, about the today 77-year-old does not want to talk. Anyone who wants to speak to them and ring their doorbell will be opened by their husband. He too will not say much, but three things are important to him. His wife had never been a spy in the service of the Stasi. The newspaper reports that the Kennedy clan had bought the silence of Ellen Rometsch with payments to a Liechtenstein account, was nothing. And what happened in Washington at that time should forever remain a purely private affair of the couple."

The newspaper went on to explain that it has a copy of a 478-page file with the code number 105-122316, that was produced by the FBI on Rometsch, although much of it has been redacted. The most interesting thing about this file is that the FBI investigators were in contact with Rometsch from July 1963 to 1987. The newspaper has also investigated her links with East German intelligence: "In the archives of the Stasi documentation authority, there is not a single record in the intelligence files about the members of the family of Ellen Rometsch, who once lived in Saxony. Together with the findings of the Western intelligence services, therefore, everything speaks for the fact that the former East German citizen has never spied for the East." (50)

Bobby Baker died on 12th November, 2017.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert A. Caro, Lyndon Baines Johnson: Master of the Senate (2002)

The waiter who brought them sandwiches at their first meeting had felt that Baker seemed "drawn to LBJ by some invisible magnet," and thereafter the attraction had only increased. "I found him fascinating from that first talk in 1948," Baker was to recall. "I was, indeed, beguiled by him." He flattered Johnson unmercifully, implored him to give him chores to carry out. Says one of Johnson's staff: "He was an unabashed lackey, a bootlicker. He'd think of all manner of excuses to come in the office and see Johnson, and he'd tell him about all the things he was doing for him, all the little ways he was helping him." "A bootlicker, but an agile one," Evan Thomas was to call him. He carried out Johnson's errands efficiently, and as quickly as he could - often at a trot. "He would scurry around the Capitol corridors, often scribbling notes as he walked " his biographer would write. "He hunched a bit as he moved, and as a result some people began to call him 'the mole,' " a description made more exact by his face, which was narrow, with a very large nose (which he later had altered) and a forehead and chin which both receded sharply, giving him a pointed-face look. He tried, somewhat unsuccessfully because he was much shorter and stooped, to stand in Johnson's commanding attitude, and to walk as he walked; he had better luck talking like Johnson: "His voice seemed to take on a bit of the Johnson twang," his biographer wrote. He was to name not one but two of his children - Lynda and Lyndon John - after him. Johnson's response was all that Baker could have wished: "You're like a son to me, because I don't have a son of my own," he told him.

(2) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

I suggested to Senator Johnson that should Kennedy ask him to join the ticket he should inquire whether Kennedy sincerely considered him (1) the most able of the availables, (2) worthy of succeeding him, and (3) whether he enjoyed the full measure of Kennedy's trust. "And if he says yes, then you've no choice but to accept. It will be your duty."

Lady Bird, who privately feared that increased political pressures might endanger her husband's heart, interrupted to express what may have been her secret hope: "Oh, I'm sure Senator Kennedy's coming to consult Lyndon. But I doubt if he's coming to ask Lyndon to run." Mrs. Rose Kennedy - she said - had raised her children to be gracious and well mannered; she concluded from this that Senator Kennedy would be paying a courtesy call as a mark of respect to his vanquished opponent. "No," John Connally said firmly. "I don't think he'd come here without wanting to do serious business. It's logical that he'll ask Lyndon to run. We've got to proceed on that assumption."

I said, "Mr. Leader, it's no disgrace to hold the second highest office in the land and be one heartbeat away from the presidency. If you reject Jack Kennedy, you'll be rejecting the Democratic party as well. It could make Kennedy angry and bitter and it could make good Democrats in the Senate angry. If you force Kennedy to turn to Senator Scoop Jackson or Governor Orville Freeman or someone even more liberal, they'll be out to gut-shoot you. In time, you could be unseated as majority leader." John Connally said, "Yes, and you're the only man who can carry the South for Kennedy. He'll never beat Nixon in Texas unless you're on the ticket."

"You've already milked everything you can out of being Senate majority leader," I said. "Likely it won't be as powerful a position with a Democrat in the White House." While Ike was president, Lyndon Johnson and Sam Rayburn had virtually dictated the Democratic program and had rebuffed the efforts of Paul Butler, Democratic national chairman, to intrude on their domain. When Butler publicly announced plans to form a liberal committee to shape the Democratic legislative program, Rayburn and Johnson had made it clear they would be their own men, thank you, and had ridden roughshod over Butler. "A strong Democratic president," I said to LBJ, "will send his own programs up from the White House. The majority leader might be no more than a figurehead or a cheerleader. I don't think you have a thing in the world to lose by running with Kennedy."

Johnson had remained passive. Then he said, "Well, I'll probably have some trouble with some of my Texas friends if I decide to run. Somebody mentioned the possibility last night to Sam Rayburn and he dismissed the idea. I don't know. I'll have to talk to Mr. Rayburn and some other people first."

Moments later Senator Kennedy was ushered into the suite. He'd apparently been able, at that early hour, to shake off pursuit by the press. We met in the living room, congratulated him, and then the two senators went into the bedroom and closed the door. Time passed slowly while Connally, Mrs. Johnson, and I chit-chatted. I think another LBJ aide or two came and went. Probably Kennedy was with Johnson no more than five or six minutes, however. When he left, with quick nods and a smile, LBJ asked us back into the bedroom.

"He asked me to run," Johnson said. LBJ reported that Kennedy said he had talked to his father, to Washington Post publisher Phil Graham, and to columnist Joe Alsop, and "They agreed with me that no one would add more to the ticket." I recall thinking it odd that JFK had mentioned no political sources, only his father and a couple of newsmen. Lyndon Johnson said, "I told him I'd have to consult with Speaker Rayburn, with my wife, and with others whose judgment I respect."

Senator Johnson's intuition that he might have trouble with his Texas friends proved correct. Speaker Rayburn quoted another Texan, former Vice-President John Nance Garner: "The office ain't worth a pitcher of warm spit." Governor Price Daniel sneered at a Kennedy-Johnson ticket as "One that would have all its strength in its hind legs." Several Texas congressmen, spoiled by LBJ's special attentions to their pet legislative schemes, begged him not to leave his powerful Senate post. These and other disenchanteds spread word of the Kennedy-Johnson flirtation; soon Senator Bob Kerr came barrelling into LBJ's hotel suite.

Kerr literally was livid. There were angry red splotches on his face. He glared at me, at LBJ, and at Lady Bird. "Get me my .38," he yelled. "I'm gonna kill every damn one of you. I can't believe that my three best friends would betray me." Senator Kerr did not seem to be joking. As I attempted to calm him he kept shouting that we'd combined to ruin the Senate, ruin ourselves, and ruin him personally. Lyndon Johnson, no slouch as a tantrum tosser himself, had little stomach for dealing with fits thrown by others; he motioned me to take Senator Kerr into the bathroom and mumbled something about explaining things to him.

Senator Kerr was a huge man-six feet four inches, and about 250 pounds - and as I turned to face him in the bathroom he slammed me in the face with his open palm. It sounded like a dynamite cap exploding in my head. I literally saw stars. My ears rang. Tears were streaming down Kerr's face as he shouted, "Bobby, you betrayed me! You betrayed me! I can't believe it!"

I couldn't believe the senator had just about knocked my head off either. No man ever hit me harder. As soon as I could talk I said, "I'm entitled to a hearing. If you'll calm down I'll give you my reasoning." Kerr was attempting to regain control, and now seemed shocked at having hit me.

I said, "Senator Kerr, everyone's underestimated Jack Kennedy from the first. They said he couldn't win because he was a Catholic, but he won the primaries. They said he would be stopped in West Virginia, but he wasn't. They said he'd be deadlocked at the convention, but that didn't happen. I think he's got a chance to beat Dick Nixon, but only if the ticket's right. If we've got a prayer of carrying the South and the Southwest, Lyndon Johnson must be on that ticket."

"But we need Lyndon in the Senate!" Kerr cried.

"Senator," I said, "if Lyndon Johnson doesn't prove to be a party loyalist now, what's his future? The ADA liberals and the Walter Reuthers and the Soapy Williamses hate his guts, just like they hate yours, and they're looking for any excuse to hurt him. One of the charges they make against him is that he's not a fully committed Democrat. Where does that leave him if he turns down his party's call?

"I know Jack Kennedy better than any of you. I think he'd be hurt and angry if Lyndon Johnson turned him down. Frankly, I think he'd cut off Senator Johnson's political pecker. And look at it this way: even if a Kennedy-Johnson ticket loses, LBJ gets better known nationally, he'll have more of a call on the nomination in 1964, and the ticket's loss will be blamed on Kennedy's religion."

"But either way, Bobby, we lose him in the Senate."

"If he's elected vice-president," I said, "he'll be an excellent conduit between the White House and the Hill. He'll still be around to consult." I knew that LBJ had arranged a Texas law permitting him to run for reelection to the Senate at the same time he sought any national office; he later, indeed, would be reelected senator from Texas and vice-president on the same day and on the same ballot. I recalled this cozy situation to Senator Kerr and finished, "So what in the world's he got to lose? I think it's a tremendous opportunity. It's a lot of pluses and I don't see the minuses."

Senator Kerr put a burly arm around me and said, "Son, you are right and I was wrong. I'm sorry I mistreated you." We shook hands. Senator Kerr whirled, marched out into the bedroom, and in turn hugged Lady Bird and Lyndon. "I'm sorry I lost my head," he apologized. "I love you dearly and if you decide to accept Kennedy's offer I'll be with you all the way."

(3) Milton Viorst, Hustlers and Heroes (1971)

Bobby Baker, like many other Senate Democrats, did everything he could to get the nomination in 1960 for Lyndon Johnson, the Majority Leader. But his influence lay in a body which - to Johnson's particular dismay - had very little to do with picking the Presidential nominee. What distinguished Baker from the rest of Lyndon's entourage, however, was that he, almost alone, argued that Johnson, failing to get the top spot, should agree to run with Kennedy as the Vice-Presidential nominee. Johnson's other friends, aware of the power of which the Majority Leader disposed, felt this was nonsense. Why Bobby persisted in this argument is by no means clear. After all, his whole orientation was toward the Senate. He knew the Vice-Presidency was an impotent office. He had no great fondness for Jack Kennedy. Yet perhaps he understood better than Lyndon that, from the parochial power base of Texas, the prospects of his becoming President were remote. Baker regarded a Kennedy-Johnson ticket as unbeatable and he thought, perhaps, that only through the Vice-presidency did Johnson have a hope of getting to the White House. But whatever the reasons, Bobby Baker, exercising his powers of persuasion long before anyone else in the entourage, was undoubtedly an important influence in Johnson's ultimate acceptance of second place on the Kennedy ticket.

(4) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

It was a story in the September issue of Vend magazine, a trade journal for the vending machine industry, that blew the lid off. The story told of my investment in Serv-U with lobbyist Fred Black, said that we'd gained many contracts while still a paper company, that we'd replaced many experienced vending companies where government contracts were the primary source of income, that we'd received liberal and instant credit from an Oklahoma bank controlled by Senator Kerr and his family, and cited Serv-U's spectacular growth. Suddenly, journalists came running in a pack. I went running to Abe Fortas and hired him to be my attorney.

Mike Mansfield sent for me; I gave him a report on the Ralph Hill Melpar situation and filled him in on how Serv-U had come about. Then I said, "If you think this will embarrass you personally, or embarrass the Senate or the Democratic party, I'm prepared to resign. I don't want to, because some might take it as an admission of guilt, but I'll do it if you think it's best." Mansfield quietly said that I was doing an excellent job for him, he had faith in me, and he wouldn't think of asking me to quit before I'd had my day in court. He issued a statement to the New York Times saying much the same.

The spate of newspaper stories set off a Pavlovian reaction in Senator John J. Williams, the Delaware Republican who liked to be labeled the "Watchdog of the Senate"; he had made a reputation by exposing the "mink coat and deep freeze" scandals involving General Harry Vaughan in the Truman administration and had contributed to the downfall of Sherman Adams, President Eisenhower's top White House assistant, when it developed that financier Bernard Goldfine had paid for vacation trips for Adams and gifted him with expensive furs. Senator Williams virtually declared open season on me, asking people who knew of my operations to come forward. One who did was my former partner in the Carousel, Geraldine Novak, whom my Serv-U Corporation had bought out with two promissory notes, the second of which was to be paid from future profits of the Carousel. Don Reynolds, the insurance man, came forward with his story of the hi-fi gift to LBJ and the advertising he had to buy on Johnson's TV and radio stations as a condition of writing a life insurance policy on him. Senator Williams was happy to announce such stories to the press.

He also presumably enjoyed breaking the story of how I'd bought the $28,000 town house Carole Tyler lived in. Lurid newspaper accounts spoke of "$7,500 worth of French wallpaper, wall-to-wall lavender carpets, and all-night parties of Washington's powerful and mighty." A great deal of hyperbole was involved. It was a nice enough house, but the furnishings were vastly inflated as to worth and style, as were the reports which sounded as if orgies occurred there with the setting of the sun.

There was an embarrassment involved, however. I had incorrectly and improperly listed Carole Tyler as my cousin when I applied for the loan, in order to satisfy the Federal Housing Authority's regulation that anyone buying an FHA-underwritten home must either live in it or have a relative living in it. At the time I gave the matter little more serious thought than would a groundhog; indeed, Carole and I had shared a laugh about it. "Well," I said to my lover, "at least you're my kissin' cousin. So it's only a little white lie."

(5) Time Magazine (6th November, 1963)

Out of the hearing room and into the arms of waiting newsmen stepped Arizona's Democratic Senator Carl Hayden, a member of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. "No comment," grumbled Hayden. Next out was Nebraska's Republican Senator Carl Curtis. "I can't tell you a thing," said he.

The remaining members of the nine-man committee were equally uncommunicative about what they had found out so far in their investigation of Bobby Gene Baker, 35, who last month precipitously resigned from his $19,600-a-year position as Secretary for the Senate Majority. Indeed, not even Delaware's Republican Senator John Williams, who appeared before the committee as a witness against Baker, would say what was going on.

Why this sudden affliction of senatorial lockjaw? The answer seemed obvious: Baker is involved in a scandal of major proportions, and the Senate plainly feared that some of its own members are in it with him. Yet the Senate's self-protective silence had an unintended effect, creating a climate in which talk and speculation flourished with tales of illicit sex, influence peddling and fast-buck financial deals.

One subject of considerable curiosity was Carole Tyler, 24, a shapely (5 ft. 6 in., 35-26-35) Tennessee girl who won the title of "Miss Loudon County" before she turned up in Washington in 1959. Three years later she was Baker's private secretary at $8,000 a year. Chain-smoking, martini-drinking, party-loving Carole also became a favorite in Baker's high-flying circle of acquaintances.

Last December Carole took up housekeeping in a cooperative townhouse at 308 N Street S.W., just a short ride from the Capitol. It was a well-furnished apartment, with prints on the walls, silk draperies in the bedrooms, lavender carpeting in the bathrooms. The parties there were lively. The twist was danced both inside the house and on the patio outside; the convivial drinking and animated chatter lasted long into the night. Some nearby residents noted that visitors appeared in the daytime as well as the evening. "A lot of people used to come through the back gate," recalls one neighbor. "That struck us as strange. Most of our guests come through the front door."

Carole shared the house for a time with another girl, Mary Alice Martin, a secretary in the office of Florida's Democratic Senator George Smathers. But neither girl owned the heavily trafficked house they lived in. The owner was Bobby Baker, who bought it for $28,000 on a down payment of $1,600. On the FHA forms that he signed, Baker listed both girls as the tenants of the house, said that Carole was his "cousin." She resigned from her job as a Senate employee at the same time Baker did, and has not since been available to inquiring newsmen.

Investigators were also sifting through stories that concerned several call girls who operated in this rarefied atmosphere. Among these was a young German woman who was asked to leave the U.S. after FBI agents showed her dossier to other interested authorities. She was Ellen Rometsch, 27, a sometime fashion model and wife of a West German army sergeant who was assigned to his country's military mission in Washington. An ambitious, name-dropping, heavily made-up mother of a five-year-old boy, Elly was a fixture at Washington parties. In September, five weeks after the Rometsches were shipped back to West Germany, her husband Rolf, 25, divorced her on the ground of "conduct contrary to matrimonial rules." Last week, while Elly hid out on her parents' farm near Wuppertal, Rolf spoke ruefully of his Washington experience, said that he "had no idea what was going on behind my back. It's a case of a woman who falls for the temptation of a sweet life her husband can't afford."

One repository of the sweet life was the Quorum Club, located in a three-room suite at the Carroll Arms Hotel, just across the street from the new Senate Office Building. Elly is remembered as a hostess there.

Bobby Baker was a leading light of the "Q Club." He helped organize it, was a charter member and served on the board of governors. The club, so its charter says, is a place for the pursuit of "literary purposes and promotion of social intercourse." Actually it was open to anyone with a literate bankroll: initiation fee, $100; yearly dues, $50. Among the 197 members are many lobbyists and several governmental figures, including Democratic Senators Frank Church of Idaho, Daniel Brewster of Maryland, J. Howard Edmondson of Oklahoma and Harrison Williams of New Jersey. Among Republican members are two Congressmen, Montana's James Battin and Ohio's William Ayres.

Many members were quick to point out that the club is a handy place to dine ("My wife is fond of the steak and sandwiches," said Bill Ayres) as well as a convenient spot for cocktails. Decorated to the male taste, the club's dimly lit interior sports prints and paintings of women with imposing façades, leather-topped card tables, a well-stocked bar, a piano and, most convenient of all, a buzzer that is wired to the Capitol so that any Senator present can be easily summoned to cast his vote on an impending issue.

The Q Club was a useful spot for meeting influential people in business and politics. Such people, in turn, were useful to Bobby Baker in his breathless pursuit of a buck. It was, by any standard, a successful pursuit, for Baker's net worth rose to something around $2,000,000. That income, presumably, enabled Baker and his wife Dorothy, who has an $11,000-a-year job with a Senate committee, to move recently into a $125,000 house near the home of Bobby's friend and longtime Senate sponsor, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, in Washington's Spring Valley section.

Though he was well liked by many people, Bobby unquestionably left behind him a roiling trough of bitter enemies. One man who thinks that Bobby did him dirt is an old friend named Ralph Hill, president of Capitol Vending Co. Hill is suing Baker for $300,000. He claims that through Bobby he got a contract for the vending-machine concession at Melpar Inc., a Virginia electronics firm. Hill charges that Baker thereafter demanded a monthly cut from Hill in return for his good will.

Hill claims that for 16 months he appeared regularly at Baker's Capitol office with envelopes containing cash - $5,600 all told. Last March the Serv-U Corp. - a competing vending-machine firm, of which Baker's law partner Ernest Tucker is board chairman - moved to buy Capitol Vending's outstanding stock. Hill resisted, and Baker warned him that he would see to it that Melpar canceled Capitol Vending's contract. Sure enough, in August 1963, Melpar said it would.

Baker's dealings with the Novak family of Washington started out pretty well. Builder Alfred Novak and his wife were friendly with the Bakers. Early in 1960, Novak agreed to lay out $12,000 so that Baker could cash in on a good stock tip. They agreed to share fifty-fifty in the profits. And they did just that. The investment brought in $75,321, and Baker got his 50% - $37,660 - without having invested a cent of his own money.

It was with the Novak family that Baker launched a $1,200,000 motel, the Carousel, in Ocean City, Md. For the Novaks the experience was a painful one. Baker, who initially invested $290,000, borrowed on promissory notes from the Serv-U Corp., began campaigning for more money from the Novaks; he wanted to build a restaurant addition to the motel, then a nightclub. The Novaks could not afford the extra investment, sold some of their shares to Baker. The Novaks were disillusioned in their partner, and Novak became deeply depressed. Five months before the Carousel opened for business, he died at 44 of a heart attack. Says Gertrude Novak of Baker's handling of financial matters: "We felt we were being pushed up against the wall."

In any event, the Carousel, billed as a "high-style hideaway for the advise and consent set," opened with a merry party. Two hundred Washington big shots traveled to the event in chartered buses. Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson were there, and Entrepreneur Baker was all over the place.

Baker also had a variety of other financial interests. Apart from his law firm, he was an agent for the Go Travel agency of Washington and invested in a Howard Johnson's motel in North Carolina. But he did not restrict himself solely to million-dollar enterprises. On at least one occasion, he showed an interest in the money problems of his Senate page boys. Young Boyd Richie was a $403-a-month telephone page in Baker's office. Richie, a 17-year-old Texan, roomed with another page, Walter J. Stewart, and paid Stewart $50 a month rent. Stewart, it seems, was on temporary military duty and so was not on the Senate payroll. One day he told Richie to give him an additional $50 a month - on orders of Bobby Baker.

For three months, Richie dutifully forked over the extra money, but the more he thought about it the angrier he became. It happened that Richie was dating Lucy Baines Johnson, L.B.J.'s 15-year-old daughter. So one evening when he came to call for Lucy, Richie confronted the Vice President in his den and told him what was going on. Next day Lyndon informed the boy that he need not continue the payoff and would be permitted to live rent-free for three months at Stewart's place to make up for his losses. Baker himself admitted that "some of Boyd Richie's money had been deferred. After all, he was just a teenager and making a good salary."

Another good Senate friend of Baker's was Oklahoma's millionaire Democrat Robert S. Kerr (Kerr-McGee Oil Industries Inc.). Before he died last January, Kerr was one of the Senate's most powerful members. At one point, Baker got a $275,000 mortgage on Serv-U Corp. from Oklahoma City's Fidelity National Bank, of which the Kerr family owns 12%.

A couple of weeks ago, Baker journeyed to Oklahoma City to see Kerr-McGee's President Dean A. McGee and the late Senator's son, Robert Jr. He said he wanted to find proof of the fact that Senator Kerr had once handed him $40,000 as a gift, told McGee that the Senator had said, "I want you to have the money. Be sure and report it on your income tax." But both McGee and young Kerr denied that the Senator had given Baker any money, insisted that there were no records of any gift. "I think I would know it if Dad had given him $40,000," says Kerr. Adds McGee: "There's only one person who really knows, and that's the Senator, and he's dead. Baker seemed to be concerned about it. He gave me the impression it was a problem."

Obviously, a lot of deep-digging investigating remained to be done before the scandalous skeins of Bobby Baker's high life could be untangled and strung back together in a definitive way. But it was just as certain that the U.S. Senate was doing itself no service by its closed-door, clam-mouthed handling of the case. For the way things were going, instead of only a handful of members suffering embarrassment or worse, the Senate and almost all its members were being subjected to suspicion.

(6) Time Magazine (6th March, 1964)

With the exaggerated gestures of a man who feels the eyes of scrutiny, the short, fox-faced witness removed his serious blue fedora, took off the velvet-collared overcoat with the lavender silk lining, and with well-manicured hands smoothed back a wisp of brown hair. His bright eyes stole briefly across the gathered crowd and looked away again. Then, clutching a black attaché case imprinted with his silver initials, Robert Gene Baker, 36, the whizbang from Pickens, S.C., hurried into a hearing room in the old Senate Office Building.

Hot-eyed TV lights glared down at the overflow of spectators lining the marble walls. Photographers jostled and cursed as they tried to get close to Baker, who himself had some difficulty squeezing through to the witness table. Bobby Baker grinned, waved to familiar faces, and, for the moment at least, appeared to be enjoying himself hugely. Finally seated, he extracted a pack of Salems from his coat pocket, laid it carefully alongside the Bible upon which he would soon be sworn in. Next he produced a typewritten sheet of paper and positioned it on the table just so.

Call It Off? His props in place, Baker nodded to some of his old employers - members of the Senate Rules Committee - who sat facing him. He also had a little joke with reporters, whom he had been assiduously avoiding. "Why don't you fellows call this whole thing off," he stage-whispered to the nearby press table, "so we can all get a rest?"

Bobby Baker was not the only one who would have liked to see the whole thing called off. His presence was a source of intense embarrassment to Democratic Senators. Up to five months ago, when he became the central figure in the gamiest Washington scandal in years, Baker was secretary to the Senate's Democratic majority.

As such, he was beyond question the U.S. Senate's most influential employee. He had been a particular protégé of the Senate's two most powerful Democrats - Oklahoma's late Senator Robert Kerr and longtime Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson. Baker made it his unending business to know things - and what he didn't know about the Senate and its members probably was not worth the trouble. He knew who was against what bill and why. He knew who was drunk. He knew who was out of town. He knew who was sleeping with whom. He influenced committee assignments. He influenced legislation. He came to be known as "the 101st Senator." And he indulged in some vast moonlighting schemes that helped him parlay his $19,612-a-year Government salary into a fortune of up to $2,000,000.

It was the public disclosure of one of those schemes that led last October to Baker's forced resignation as Senate majority secretary. Ever since, the Rules Committee, chaired by North Carolina's colorless, cautious Senator B. Everett Jordan, has been investigating the Baker case.

(7) W. Penn Jones Jr, Texas Midlothian Mirror (31st July, 1969)

Bobby Baker was about the first person in Washington to know that Lyndon Johnson was to be dumped as the Vice-Presidential candidate in 1964. Baker knew that President Kennedy had offered the spot on the ticket to Senator George Smathers of Florida... Baker knew because his secretary. Miss Nancy Carole Tyler, roomed with one of George Smathers' secretaries. Miss Mary Jo Kopechne had been another of Smathers' secretaries. Now both Miss Tyler and Miss Kopechne have died strangely.

(8) G. R. Schreiber, The Bobby Baker Affair (1964)

Once the cat was out of the bag that Bobby Baker, a married man, had bought a townhouse for his beautiful young secretary, it was inevitable that girls would begin to figure in the Senate's much heralded investigation of Bobby's outside activities. As it happens, girls figure in much that goes on in Washington, both because there are so many of them in the myriad government offices and because Washington is a city on a perpetual party. And what are parties - cocktail or otherwise - without pretty girls?

Single girls outnumber other people by a wide margin in Washington. A passably attractive girl in a government office can go off to a party seven nights out of seven if she is so inclined. She can go with a male fellow worker who prefers not to take his wife. Or she can be window dressing (more if she prefers) at the parties given by the free spending lobbyists. There are always business executives from out of town who hate to eat alone.

A girl in Washington, like most girls anywhere, can go out as often and as far as her schedule and her scruples allow. The difference between Washington and other cities is that there are so many more opportunities.

Nancy Carole Tyler had come up to Washington from Lenoir City, Tennessee, a town of five thousand citizens some twenty miles from Knoxville. She had big bright eyes, a good figure, a determined chin, and a certificate to prove she had been named Miss Loudon County of 1957. Her first job was on the secretarial staff of a congressman from Delaware. Miss Loudon County got her picture in the Washington newspapers for the first time when she was photographed in 1960 at a statue raising ceremony at the Capitol. The newspapers reported that Miss Tyler had posed for the arms of the statue "Peace." It may have been that Bobby saw the photograph of Miss Loudon County, her long brown hair tumbling to her shoulders, a wide smile crinkling her eyes and showing her beautifully even teeth. Whether Bobby saw the picture or not, Nancy Carole moved over from the House of Representatives to the office of the secretary to the senate majority in February, 1961, and ever after where Bobby was, there was Nancy.

Nancy Carole joined Bobby's staff with the title of telephone page for the majority, a job which paid her $5,687.56 to start. Her work was more than satisfactory and she was rewarded with a fast series of pay raises. Almost two months to the day after she joined Bobby's staff she got her first increase to $6,052.11. Four months later, in August, 1961, her salary was boosted to $6,538.19 and that October - eight months after she joined his staff Bobby promoted Nancy Carole to clerk for the secretary to the majority, a kind of administrative assistant, and raised her pay to $7,753.34.

October 16, 1962, one month before she moved into the townhouse Bobby purchased, Nancy Carole's salary was boosted again, this time to $8,296.07. All in all it was a history of consistently good merit increases and the take home pay was not at all bad for the twenty-three-year-old Miss Loudon County. Bobby wrote out a check to cover the down payment on the $28,800 townhouse and wrote checks for the $238 monthly payments, so Nancy Carole had enough left over from her salary to give lots of parties on her own in her attractive patio.

(9) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

The fat was in the fire, of course, when the ever-bellicose senator John J. Williams (chairman of the Rules Committee investigating Baker), an avid reader of Jack Andersen's column, learned there that I was an official of the Quorum Club and that Ellen Romesch - who'd once had an affair with a Soviet embassy attaché - had been seen in that club. Suddenly, Ellen Romesch was the greatest threat to national security since Alger Hiss. Attorney General Robert Kennedy had her rush-deported to Germany - sending as her escort, oddly enough, a trusted aide with whom the lady fell in love, causing her to write a series of embarrassingly intimate letters to him, which now are in my possession - in order to save the Republic. What the newspapers did not say, possibly because I've never admitted it before - but which Robert Kennedy definitely knew - was that Ellen Romesch had been one of the women Jack Kennedy had asked me to introduce him to. I accommodated his request.

(10) Merle Miller, Lyndon: An Oral Biography (1980)

The Senate investigators that day agreed that since Reynolds' testimony was so fascinating, they would not adjourn for lunch, and thus they did not learn until late afternoon that Jack Kennedy had been assassinated and Lyndon Johnson had become president, which changed things considerably. It is, or was then, one thing to look into the affairs of a vice-president, and quite another to examine those of a president, particularly when he had become president under such adverse circumstances.

Before they learned they had a new president, however, the investigators were told by Reynolds that he had sent the Johnson family a $585 Magnavox stereo set chosen, he said, by Mrs. Johnson. And he had a copy of a receipt - he kept a copy of everything, as men of his kind often do - which showed that the set had in fact been charged to him and had been shipped in a government car to 4921 Thirtieth Place, where the Johnsons had lived.

Naturally, all of Reynolds' testimony was leaked to the press, but it might have made larger headlines had Lyndon Johnson still been a largely powerless vice-president. Now most newspapers were inclined to play down the stories.

Most of the new president's advisers told him to ignore Reynolds, but Abe Fortas counseled him to tell his story to the public. So Johnson called a press conference in which he said that the Baker family had given the Johnson family the stereo. He said the families frequently exchanged gifts; he said further that he and Lady Bird had used the stereo for a period. What happened after that was rather vague; apparently the set had been given to some other friendly family. Who, why, and whether or not the Baker family often sent such expensive gifts to the Johnson family would forever remain a mystery.

(11) Edward Jay Epstein, Esquire Magazine (December, 1966)

In January of 1964 the Warren Commission learned that Don B. Reynolds, insurance agent and close associate of Bobby Baker, had been heard to say the FBI knew that Johnson was behind the assassination. When interviewed by the FBI, he denied this. But he did recount an incident during the swearing in of Kennedy in which Bobby Baker said words to the effect that the s.o.b. would never live out his term and that he would die a violent death.

(12) Bobby Baker, interviewed in 1990.

Murchison owned a piece of Hoover. Rich people always try to put their money with the sheriff, because they're looking for protection. Hoover was the personification of law and order and officially against gangsters and everything, so it was a plus for a rich man to be identified with him. That's why men like Murchison made it their business to let everyone know Hoover was their friend. You can do a lot of illegal things if the head lawman is your buddy.

(13) Robert A. Caro, Lyndon Baines Johnson: Master of the Senate (2002)

Jenkins wrote Warren Woodward on January 11, "Ed Clark tells me that he has received some assistance from H. E. Butt. I wonder if you could go by and pick it up and put it with the other (we) put away before I left Texas Clark says that Brown's money was for the presidential run for which Johnson was gearing up that January, and that Butt's was for Johnson to contribute to the campaigns of other senators, but that often he and the other men providing Johnson with funds weren't even sure which of these two purposes the funding were for. "How could you know?" Ed Clark was to say. "If Johnson wanted to give some senator money for some campaign, Johnson would pass the word to give money to me or Jesse Kellam or Cliff Carter, and it would find its way into Johnson's hands. And it would be the same if he wanted money for his own campaign. And a lot of the money that was given to Johnson both for other candidates and for himself was in cash." "All we knew was that Lyndon asked for it, and we gave it," Tommy Corcoran was to say.

This atmosphere would pervade Lyndon Johnson's fundraising all during his years in the Senate. He would "pass the word" - often by telephoning, sometimes by having Jenkins telephone - to Brown or dark or Connally, and the cash would be collected down in Texas and flown to Washington, or, a Johnson was in Austin, would be delivered to him there. When word was received that some was available, John Connally recalls, he would board a plane in Fort Worth or Dallas, and "I'd go get it. Or Walter would get it. Woody would go get it. We had a lot of people who would go get it, and deliver it. The idea that Walter or Woody or Wilton Woods would skim some is ridiculous. We had couriers." Or, dark says, "If George or me were going up anyway, we'd take it ourselves." And Tommy Corcoran was often bringing Johnson cash from New York unions, mostly as contributions to liberal senators whom the unions wanted to support. Asked how he knew that the money "found its way" into Johnson's hands, Clark laughed and said, "Because sometimes I gave it to him. It would be in an envelope." Both Clark and Wild said that Johnson wanted the contributions given, outside the office, to either Jenkins or Bobby Baker, or to another Johnson aide. Cliff Carter, but neither Wild nor Clark trusted either Baker or Carter.

(14) Phil Brennan, Some Relevant Facts About the JFK Assassination (2003)

There's an explosive new book that lays out a very detailed - and persuasive - case for the probability that the late President Lyndon Baines Johnson was responsible for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

I say persuasive because the author, Barr McClellan, was one of LBJ's top lawyers, and he provides a lot of information hitherto unknown to the general public - much more of which he says is buried in secret documents long withheld from the American people....

McClellan and others before him have discussed the fact that LBJ faced some pretty awful prospects, including not only being dumped from the 1964 ticket but also spending a long, long time in the slammer as a result of his role in the rapidly expanding Bobby Baker case - something few have speculated about because the full facts were never revealed by the media, which didn't want to know, or report, the truth...

Bobby Kennedy, called five of Washington's top reporters into his office and told them it was now open season on Lyndon Johnson. It's OK, he told them, to go after the story they were ignoring out of deference to the administration.

And from that point on until the events in Dallas, Lyndon Baines Johnson's future looked as if it included a sudden end to his political career and a few years in the slammer. The Kennedys had their knives out and sharpened for him and were determined to draw his political blood - all of it.

In the Senate, the investigation into the Baker case was moving quickly ahead. Even the Democrats were cooperating, thanks to the Kennedys, and an awful lot of really bad stuff was being revealed - until Nov. 22, 1963.

By Nov. 23, all Democrat cooperation suddenly stopped. Lyndon would serve a term and a half in the White House instead of the slammer, the Baker investigation would peter out and Bobby Baker would serve a short sentence and go free. Dallas accomplished all of that.

(15) Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (1993)

According to President Kennedy's secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, Bobby Kennedy was also investigating Bobby Baker for tax evasion and fraud. This had reached the point where the President himself discussed the Baker investigation with his secretary, and allegedly told her that his running mate in 1964 would not be Lyndon Johnson. The date of this discussion was November 19, 1963, the day before the President left for Texas.

A Senate Rules Committee investigation into the Bobby Baker scandal was indeed moving rapidly to implicate Lyndon Johnson, and on a matter concerning a concurrent scandal and investigation. This was the award of a $7-billion contract for a fighter plane, the TFX, to a General Dynamics plant in Fort Worth. Navy Secretary Fred Korth, a former bank president and a Johnson man, had been forced to resign in October 1963, after reporters discovered that his bank, the Continental National Bank of Fort Worth, was the principal money source for the General Dynamics plant.

(16) David E. Scheim, The Mafia Killed President Kennedy (1988)

While ignoring the Mob in his official capacity. Hoover was less exclusive in his personal relationships. He often stayed for free at the Las Vegas hotels of construction tycoon Del E. Webb, whose holdings were permeated with organized crime entanglements. Hoover and Webb also met frequently on vacations in Del Mar, California. During Hoover's annual trips to that city's luxurious Del Charro Motel, his bill was paid by its owner, Clint Murchison, Jr., Hoover's "bosom pal. Murchison, a Texas oil tycoon who backed Lyndon Johnson, was questionably involved with both the Teamsters and Bobby Baker, infamous LBJ aide whose misdeeds will be discussed. But Hoover continued to accept Murchison's hospitality, even while Murchison's dealings with Baker were being investigated by both the Senate and Hoover's own FBI.

(17) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

One Sunday evening I was consulting with Abe Fortas at his home when Lady Bird Johnson called... I hardly heard her. I was thinking: LBJ's right there by her side, but he won't talk to me because he wants to be able to say he hasn't. I knew that Johnson was petrified that he would be dragged down... LBJ was already nervous because of the Billie Sol Estes scandal and the resignation of a Texas friend, Fred Korth, who'd quit as secretary of the navy following conflict-of-interest accusations. So I'd not expected to hear much from him. In fact, from the moment I resigned in October of 1963 until I visited him at his ranch to see a dying man, almost nine years later, we spoke not a word and communicated only through intermediaries.

(18) Milton Viorst, Hustlers and Heroes (1971)

After a hard day at the Senate, when anyone else would be glad to get home to bed, Bobby Baker would be starting the evening's fun with the Mexican hat dance. The frolic might go on till dawn. Bobby's secretary was Carole Tyler, a Tennessee beauty with whom he was often seen in public. Carole's place in Southwest Washington, an upper-middle-class redevelopment area of closely packed high-rises and town houses, became the center where Bobby's friends, male and female, often met. How Bobby spent his off-duty hours was more or less common knowledge on the Hill, but those were the days when Bobby was on top, when there seemed nothing unusual about his diversions and when no one thought that, as Senate practices go, there was anything there to get excited about...

The... sex's arrow struck again, when a neighbor of Carole Tyler's, a newspaper reporter, discovered, in scanning the list of eligible voters in the residential co-op, that Bobby Baker was actually the owner of Carole's house, now widely known for its lavender carpet (the same, by the way, with which the Baker bedroom in Spring Valley and the lobby of the Carousel are decorated). In explanation, Bobby has since declared: "She and her roommate were paying $250 a month for an apartment. I fussed at her. I said you're getting up old enough where you ought to be building up a little equity in a place. So they went and they found a place that they wanted. And because they didn't have the net worth to get it, I agreed to put a financial statement in whereby they could get it and build up some equity. Is that criminal or illegal or un-American to try to help two young ladies build up equity?" But the public was scarcely interested in looking at Carole's house as a token of philanthropy. It became a tourist attraction and dozens of gawkers passed it in their cars. But Bobby was undeterred. He continued to give parties there regularly. If he encountered an old Senate acquaintance, many of whom lived in the neighborhood, he didn't turn up his coat collar but, on the contrary, said in his usual friendly way, "Hello, how are you? Nice to see you again." On weekends he even washed Carole's car in the parking lot. If Bobby was, in reality, embarrassed by his publicity, he managed to conceal it very well...

Carole Tyler used to be a normal visitor to the Carousel. Her figure was familiar on the beach and in the bar. Then, in May, 1965, she was killed. Carole was joyriding in a Waco biplane, when the pilot made a flip, failed to pull out in time and plunged into the Atlantic directly in front of the motel. Bobby was there when they brought her body ashore. He knew that the assembled crowd, mostly townspeople in threadbare clothes, expected him to say something appropriate. But there wasn't much you could say about Carole, beyond noting that she was a very pretty girl from a small town in Tennessee who found zest in Washington and lived her life with more gusto than it required. Her friends agreed later that she had chosen a kicky way to go. "All I can say," Baker uttered finally to the bystanders, "is that she was a very great lady." Baker was more accurate than that in taking head counts in the Senate. Whatever Carole was, that wasn't it. But Bobby had style and he wasn't going to let Carole, who was dear to him, leave the world without some of it as adornment.

(19) Larry Hancock, Someone Would Have Talked (2003)

Baker went to great lengths in his own book to relate his business activities and even his financing to Senator Kerr of Oklahoma, merely mentioning that "additional" investment came from a "hotel-casino" man named Eddie Levinson and a Miami investor and gambler Benjamin B Sigelbaum.

He makes only brief mention that Fred Black had helped him with introductions to Levinson and Sigelbaum.

Baker describes Fred Black as a "super lobbyist" for North American Aviation, among other clients. We are already familiar with Black as a close friend and long time associate of John Roselli. Black's importance to both Baker and Johnson may be further indicated in an April 21 telephone call from President Johnson to Cyrus Vance, a call in which Johnson indicated to Vance that he was especially sensitive to charges of corruption.

He instructed Vance to ensure that the press should find no grounds for charges of bribery in his administration. The call had been prompted by newspaper coverage of the trial of Fred Black in which Black had been charged with taking $150,000 on behalf of the Howard Foundry Company to intervene with the Air Force in a $2.7 million claim against that firm. 360 The Chicago-based Howard Foundry was one of Black's two employers of record, paying him $2,500 per month while North American paid him $14,000 a month.

(20) Robert Kennedy was interviewed by John Bartlow Martin in April 1964. The interview appeared in Robert Kennedy: His Own Words (1988)

John Martlow Martin: The Bobby Baker case broke in November. Do you want to go into the Bobby Baker case?

Robert Kennedy: I can go into it. I really didn't follow it particularly or get into it very much. The newspapers had a number of articles, The Washington Post particularly. I had always heard stories about Bobby Baker, about all his money and free use of money. My relationship with him always had been reasonably friendly, although I didn't have much to do with him. Even though he was opposed to President Kennedy - he was working for Lyndon Johnson - he was always quite reasonable about it. He certainly didn't create any bitterness on our part. So I was reasonably friendly toward him. Our first involvement in it came, I suppose, in a conversation I had with Ben Bradlee (then the Washington Bureau Chief of Newsweek), who had some information. I can't remember exactly what it was, but they printed it in Newsweek. He asked me if we would look into it, and I said we would look into it.

Subsequently, there were a lot of stories that my brother and I were interested in dumping Lyndon Johnson and that I'd started the Bobby Baker case in order to give us a handle to dump Lyndon Johnson. Well, number one, there was no plan to dump Lyndon Johnson. That didn't make any sense. Number two, I hadn't gotten really involved in the Bobby Baker case until after a good number of newspaper stories had appeared about it. There really wasn't any choice but to look into some of the allegations, which were allegations of violations of law. Some weeks after that, I called (Baker) - I suppose sometime in November - and said that I just wanted to assure him that he'd get a fair shake. If there were any problem, he could send his lawyer to the Department of Justice and he would be fairly treated. Abe Fortas was his lawyer. There were a lot of stories then, after November 22, that the Bobby Baker case was really stimulated by me and that this was part of my plan to get something on Johnson. That wasn't correct.

(21) Robert Kennedy was interviewed by Anthony Lewis in December 1964. The interview appeared in Robert Kennedy: His Own Words (1988)

Anthony Lewis: Speaking of Mr. Hoover, did you ever have the feeling, in dealing with Mr. Hoover, that he knew a very great deal about you personally? I mean, did he ever make this evident? This is, at least by way of story, of legend, something he's supposed to do?