The Warren Commission

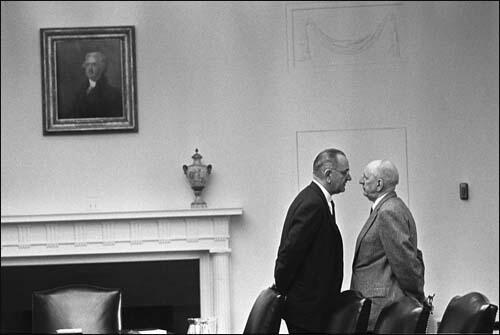

After the death of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." The seven man commission was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and included Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs. (1)

Lyndon B. Johnson also commissioned a report on the assassination from J. Edgar Hoover. Two weeks later the Federal Bureau of Investigation produced a 500 page report claiming that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole assassin and that there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The report was then passed to the Warren Commission. Rather than conduct its own independent investigation, the commission relied almost entirely on the FBI report. According to Gerald D. McKnight, the author of Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005): "Hoover and his executive officers at FBIHQ intended to control the Commission to assure that it ratified the solution to the assassination decided upon by the government over the first weekend." (2)

At the first meeting of the Warren Commission, Allen W. Dulles handed out copies of a book to help define the ideological parameters he proposed for the Commission's forthcoming work. "American assassinations were different from European ones, he told the Commission. European assassinations were the work of conspiracies, whereas American assassins acted alone." John J. McCloy said that it was of paramount importance to "show the world that America is not a banana republic, where a government can be changed by conspiracy." Chief Justice Earl Warren said at the same meeting, "We can start with the premise that we can rely upon the reports of the various agencies that have been engaged in the investigation." (3)

Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs all questioned the FBI report that suggested a single-bullet (CE 399) had inflicted all seven non-fatal wounds of President John F. Kennedy and Governor John B. Connally. John J. McCloy also initially had doubts about the single bullet theory, he came around to it, siding with Allen W. Dulles and Gerald Ford. Russell phoned up President Lyndon B. Johnson and said: "They're trying to prove that the same bullet that hit Kennedy first was the one that hit Connally, went through him and through his hand, his bone, and into his leg... the Commission believes that the same bullet that hit Kennedy hit Connally. Well, I don't believe it!" Johnson's reply was "I don't either." (4)

Nellie Connally, who was in the same car as her husband later told Walter Cronkite: "The first sound, the first shot, I heard, and turned and looked right into the President's face. He was clutching his throat, and just slumped down. He Just had a - a look of nothingness on his face. He didn't say anything. But that was the first shot. The second shot, that hit John - well, of course, I could see him covered with - with blood, and his - his reaction to a second shot. The third shot, even though I didn't see the President, I felt the matter all over me, and I could see it all over the car." John Connolly. added: "Beyond any question, and I'll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me." (5)

The Warren Commission's own medical and forensic experts asserted that the medical and physical evidence was inconsistent with the single-bullet theory. Richard B. Russell and John S. Cooper forced a special Warren Commission executive session to register their dissent on the single-bullet theory. However, Chief Justice Earl Warren and General Counsel J. Lee Rankin saw to it that this strongly felt objection was suppressed from the official record. (6)

When dealing with this issue in the report it stated: "Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connolly., there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connolly.'s wounds. However, Governor Connolly.'s testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some differences of opinion as to this probability. (7)

The Warren Commission was published in October, 1964. It reached the following conclusions:

(i) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connolly. were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(ii) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(iii) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connolly., there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connolly.'s wounds. However, Governor Connolly.'s testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connolly.'s wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(iv) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connolly. were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(v) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(vi) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(vii) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(viii) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(ix) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone. (8)

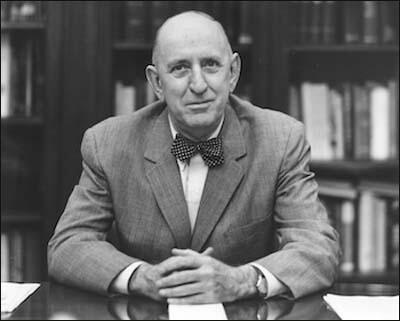

Richard B. Russell continued to argue that the Warren Commission Report was not an accurate account of what happened. Russell mistrusted CIA testimony based on past dealings with the agency and was deeply unsatisfied with what he saw as the lack of depth with the Warren Commission's investigation. Russell attacked both the single bullet theory and the lone assassin notion in an interview published in The Atlanta Constitution (9).

In an interview with WSB-TV in February 1970, less than a year before his death, Russell again voiced doubts about parts of the Warren Report. Russell also told The Washington Post that he believed that Oswald had encouragement to kill Kennedy and asserted that the members of the Commission "weren't told the truth about Oswald". The CIA did not tell the Warren Commission that they had been watching Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City and they also omitted that they had engaged in numerous operations to try to assassinate Fidel Castro. (10)

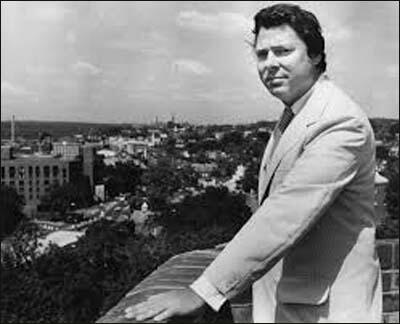

John S. Cooper publicly criticized the conclusion of the Warren Commission as "premature and inconclusive" and told Robert Kennedy and Edward Kennedy in 1964 that he didn't believe Oswald had acted alone. Thomas H. Boggs was the most opposed to the idea of a lone gunman. According to Bernard Fensterwald: "Almost from the beginning, Congressman Boggs had been suspicious over the FBI and CIA's reluctance to provide hard information when the Commission's probe turned to certain areas, such as allegations that Oswald may have been an undercover operative of some sort. When the Commission sought to disprove the growing suspicion that Oswald had once worked for the FBI, Boggs was outraged that the only proof of denial that the FBI offered was a brief statement of disclaimer by J. Edgar Hoover. It was Hale Boggs who drew an admission from Allen Dulles that the CIA's record of employing someone like Oswald might be so heavily coded that the verification of his service would be almost impossible for outside investigators to establish." According to one of his friends: "Hale felt very, very torn during his work (on the Commission) ... he wished he had never been on it and wished he'd never signed it (the Warren Report)." Another former aide argued that "Hale always returned to one thing: Hoover lied his eyes out to the Commission - on Oswald, on Ruby, on their friends, the bullets, the gun, you name it." (11)

Thomas H. Boggs came under considerable pressure when he began questioning the Warren Report. On 5th April 1971, Boggs made a speech on the floor of the House accusing the FBI of tapping his phones and keeping dossiers on members of Congress. Boggs said the files consisted of information on seven persons who had written critically of the commission's findings. He accused J. Edgar Hoover, of being "incompetent and senile" and that the FBI under Hoover's most recent years "adopted the tactics of the Soviet Union and the Hitler's Gestapo." (12)

Ron Kessler, reported in the Washington Post that his son Thomas Hale Boggs Jr claimed that the FBI had mounted a smear campaign against Boggs because of his criticism of the Warren Commission Report. "The material, which Thomas Boggs made available, includes photographs of sexual activity and reports on alleged communist affiliations of some authors of articles and books on the assassination." (13) He said these dossiers had been compiled by the FBI on Warren Commission critics in order to discredit them. "Mr. Boggs said the files consisted of information on seven persons who had written critically of the commission's findings." (14)

Thomas Hale Boggs disappeared while on a campaign flight from Anchorage to Juneau, Alaska, on 16th October, 1972. Also killed in the accident was Nick Begich, a member of the House of Representatives. No bodies were ever found and in 1973 his wife, Lindy Boggs, was elected in her husband's place. (15) The Los Angeles Star, on November 22, 1973, reported that before his death Boggs claimed he had "startling revelations" on Watergate and the assassination of John F. Kennedy. (16)

Leo Janos interviewed Lyndon B. Johnson in July 1973: "During coffee, the talk turned to President Kennedy, and Johnson expressed his belief that the assassination in Dallas had been part of a conspiracy. 'I never believed that Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger.' Johnson said that when he had taken office he found that 'we had been operating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean.' A year or so before Kennedy's death a CIA-backed assassination team had been picked up in Havana. Johnson speculated that Dallas had been a retaliation for this thwarted attempt, although he couldn't prove it." (17)

In later life John S. Cooper also admitted that he was convinced that there had been a conspiracy to kill John F. Kennedy. Cooper told Morris Wolff: "They have it all wrong. They refuse to look at the facts. The forensics are right there. One bullet came in from the front, and the President grabbed his neck, and his head shot back in the open limousine. The car had slowed down in front of the Texas School Depository. The next shot came in from the back, from a window on the 7th floor, the top floor of the Book Depository building on Dealey Plaza. A third shot came from behind the motorcade, jerking his head backward as he slowly passed the area. It was the shot fired by Lee Harvey Oswald, one of two or three killers. At least two were active that day, one from in front and the second from the back. The forensics clearly show there were at least two separate shooters, and they were standing in different places, one from the grassy knoll and one high in the office building. Our new President, Lyndon Baines Johnson, now wants to cover up and move on. I want to delay and get all the facts. They are covering the facts and putting their collective heads in the sand. LBJ pretends to give me the green light to press forward with the investigation. But he is secretly telling the others to bring the hearings to a quick close…. They want to bury the truth under a pile of stones. I think Lyndon Baines Johnson was involved in the planning and execution of Kennedy's death." (18)

Gerald Ford, who had always publicly loyally supported the conclusions of the Warren Report but he privately did not believe it. President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing of France met Ford when he was president. He said in an interview with Gaëtane Morin: "Once I was making a car trip with him, he was then President as I was myself. I said to him: 'Let me ask you an indiscreet question: you were on the Warren Commission, what conclusions did you arrive at?" Ford replied: "We arrived at an initial conclusion: it was not the work of one person, it was something set up. We were sure that it was set up. But we were not able to discover by whom. We have concluded that this assassination was planned. There was a conspiracy. But we have not been able to identify which organization ordered it." (19)

In 1982 Doug Thompson became friends with John B. Connolly. "Connolly was both gracious and charming and told us many stories about Texas politics. As the evening wore on and the multiple bourbon and branch waters took their effect, he started talking about November 22, 1963, in Dallas. 'You know I was one of the ones who advised Kennedy to stay away from Texas,' Connolly. said 'Lyndon (Johnson) was being a real asshole about the whole thing and insisted.' Connolly.'s mood darkened as he talked about Dallas. When the bullet hit him, he said he felt like he had been kicked in the ribs and couldn't breathe. He spoke kindly of Jackie Kennedy and said he admired both her bravery and composure. I had to ask. Did he think Lee Harvey Oswald fired the gun that killed Kennedy? 'Absolutely not,' Connolly. said. 'I do not, for one second, believe the conclusions of the Warren Commission.' So why not speak out? 'Because I love this country and we needed closure at the time. I will never speak out publicly about what I believe.' He died in 1993 and, I believe, never spoke publicly about how he doubted the findings of the Warren Commission."

Thompson went on to argue: Connally's note serves as yet another reminder that in our Democratic Republic, or what's left of it, few things are seldom as they seem. Like him, I never accepted the findings of the Warren Commission. Too many illogical conclusions. John Kennedy's death, and the doubts that surround it to this day, marked the beginning of the end of America's idealism. The cynicism grew with the lies of Vietnam and the senseless deaths of too many thousands of young Americans in a war that never should have been fought. Doubts about the integrity of those we elect as our leaders festers today as this country finds itself embroiled in another senseless war based on too many lies. John Connolly. felt he served his country best by concealing his doubts about the Warren Commission's whitewash but his silence may have contributed to the growing perception that our elected leaders can rewrite history to fit their political agendas. Had Connolly. spoken out, as a high-ranking political figure with doubts about the 'official' version of what happened, it might have sent a signal that Americans deserve the truth from their government, even when that truth hurts." (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Kai Bird, The Chairman: John J McCloy & The Making of the American Establishment (2017) pages V–VI.

At the first meeting of the newly constituted Warren Commission, Allen Dulles handed out copies of a book to help define the ideological parameters he proposed for the Commission's forthcoming work. American assassinations were different from European ones, he told the Commission. European assassinations were the work of conspiracies, whereas American assassins acted alone. Someone was alert enough to remind Dulles of the Lincoln assassination, when Lincoln and two members of his cabinet were shot simultaneously in different parts of Washington. But Dulles was not stopped for a second: years of dissembling in the name of "intelligence" were not to fail him in this challenge. He simply retorted that the killers in the Lincoln case were so completely under the control of one man (John Wilkes Booth), that the three killings were virtually the work of one man.

Dulles's logic here (or, as I prefer to call it, his paralogy) was not idiosyncratic, it was institutional. As we have seen, J. Edgar Hoover had already, by November 25, committed his own reputation and the Bureau to the conclusion that Oswald had done it, and acted alone. Chief Justice Warren knew this, yet said at the same meeting, "We can start with the premise that we can rely upon the reports of the various agencies that have been engaged in the investigation."

(2) Recorded telephone conversation between Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard B. Russell (18th September, 1964)

Richard Russell: That danged Warren Commission business, it whupped me down so. We got through today. You know what I did? I... got on the plane and came home. I didn't even have a toothbrush. I didn't bring a shirt.... Didn't even have my pills-antihistamine pills to take care of my em-fy-see-ma.

Lyndon B. Johnson: Why did you get in such a rush?

Richard Russell: I'm just worn out, fighting over that damned report.

Lyndon B. Johnson: Well, you ought to have taken another hour and gone get your clothes.

Richard Russell: No, no. They're trying to prove that the same bullet that hit Kennedy first was the one that hit Connally, went through him and through his hand, his bone, and into his leg... I couldn't hear all the evidence and cross examine all of them. But I did read the record.... I was the only fellow there that ... suggested any change whatever in what the staff got up.' This staff business always scares me. I like to put my own views down. But we got you a pretty good report.

Lyndon B. Johnson: Well, what difference does it make which bullet got Connally?

Richard Russell: Well, it don't make much difference. But they said that... the commission believes that the same bullet that hit Kennedy hit Connally. Well, I don't believe it.

Lyndon B. Johnson: I don't either.

Richard Russell: And so I couldn't sign it. And I said that Governor Connally testified directly to the contrary and I'm not gonna approve of that. So I finally made them say there was a difference in the commission, in that part of them believed that that wasn't so. And of course if a fellow was accurate enough to hit Kennedy right in the neck on one shot and knock his head off in the next one - and he's leaning up against his wife's head - and not even wound her - why, he didn't miss completely with that third shot. But according to their theory, he not only missed the whole automobile, but he missed the street! Well, a man that's a good enough shot to put two bullets right into Kennedy, he didn't miss that whole automobile... But anyhow, that's just a little thing.

Lyndon B. Johnson: What's the net of the whole thing? What's it say? Oswald did it? And he did it for any reason?

Richard Russell: Just that he was a general misanthropic fellow, that he had never been satisfied anywhere he was on earth - in Russia or here. And that he had a desire to get his name in history.... I don't think you'll be displeased with the report. It's too long.... Four volumes.

Lyndon B. Johnson: Unanimous?

Richard Russell: Yes, sir. I tried my best to get in a dissent, but they'd come round and trade me out of it by giving me a little old threat.

(3) Gerald D. McKnight, Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005)

The FBI had a fairly extensive pre-assassination file on Lee Harvey Oswald, but the first reports on Oswald to cross the director's desk originated with military intelligence. Hoover imposed his own interpretation on the army's intelligence reports on Oswald that fitted neatly into his version of assassination history. Two hours later, while on the phone with Assistant Attorney General Schlei, Hoover gave the Justice Department official the benefit of his reading of U.S. history and the political leanings of presidential assassins. It was the director's considered opinion that such killers were always either "anarchists" or "communists." Later in the day the Dallas field office, after prodding from FBIHQ, started compiling biographical material from Oswald's FBI file and interview sessions at Dallas police headquarters with the alleged assailant. An FBI agent lifted some of this material from Oswald's wallet when the suspect left the interrogation room to relieve himself. One of the items receiving special attention was a "Fair Play for Cuba, New Orleans Chapter" membership card issued to L. H. Oswald by chapter president A. J. Hidell, which was assumed to be a fictitious name for Oswald himself. Later that same day FBI HQ had a chance to review the agency's pre assassination file on Oswald. The salient biographical data in the file strengthened Hoover's conviction that Oswald was the assassin: In 1959 Oswald had told U.S. Embassy officials in Moscow that he was a "Marxist" and wished to renounce his American citizenship. In exchange for Soviet citizenship, he offered to tell the Soviets what he knew about the U.S. Marine Corps and his specialty as a radar operator. The ex-marine had distributed pro-Castro "Fair Play for Cuba" literature in New Orleans and, according to a "confidential informant," Oswald subscribed to The Worker, the East Coast organ of the American Communist Party. ''

Before the day was over the biographical details about Oswald were fitted to Hoover's profile of a presidential assassin. That same day, the word went out from FBI HQ to the Dallas field office that Oswald was not just the principal suspect; he was the only suspect. A Richardson, Texas, law officer called the FBI Dallas office the afternoon of the assassination with the name of a possible suspect, Jimmy George Robinson, and other members of the white supremacist National States Rights Party because of their open hatred for President Kennedy. Before the office memo recording the call was serialized and filed-and it was filed the day of the assassination-it carried the handwritten notation: "Not necessary to cover as true suspect located." In short, within a few hours of the assassination, the FBI was not interested in any possible conspiracy or any suspect other than Lee Harvey Oswald. No action was taken on the lead from Richardson, although the call came in before the Dallas authorities charged Oswald with killing President Kennedy. He was not charged with JFK's murder until 11:25 p.m.

(4) Gerald D. McKnight, Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005)

Under Hoover's direction the FBI's handling of Oswald's Mexico City activities was simply a repetition of the way the director and bureau elites dealt with the larger, controlling issue of the assassination itself. That is to say, the politically determined theory of the crime-Oswald acting alone took the president's life-took iron-clad, unamendable precedence over all the evidence and witness testimony. President Johnson and Hoover had agreed on the "official truth" of Dallas over the weekend following the assassination. When LBJ, anxious to "settle the dust" of Dallas, asked that the FBI report on the assassination be on his desk by Tuesday, November 26, the day after Kennedy was buried, Hoover notified the General Investigative Division "to wrap up investigation; seems to me we have the basic facts now:"" Only two developments delayed for the moment this rush to judgment: The first was Hoover's suspicion regarding Oswald's assassin, Jack Ruby, and his easy access to Oswald in the basement of the Dallas police department. The second unanticipated development was the revelation from Mexico City about an Oswald imposter and a possible KGB-Castro conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy.

As soon as FBI Washington had proved that the Alvarado story was bogus and conspired with the CIA to suppress from the Commission any revelations about an Oswald imposter, Hoover closed the book on any further FBI investigation into the "potential Cuban aspects" surrounding Oswald and his seven days in Mexico City. It would have been expected that the FBI's General Investigative Division (GID) would carry the major responsibility in any legitimate investigation into the Kennedy assassination. Up to a point, this was true. The FBI report that LBJ wanted on his desk by November 26 was prepared by the GID. According to Assistant Director Alex Rosen, the head of that division, the "basic investigation was substantially completed by November 26, 1963," to meet the White House's expectations." After the GID turned in its thrown-together report the division was relegated to the margins of the investigation. Rosen himself was assigned to the bureau's bank-robbery desk. The GID head would later characterize the FBI's investigative efforts into the Kennedy assassination as "standing around with pockets open waiting for evidence to drop in." Even more telltale was Hoover's order on November 23 to cancel all bureau contacts with Cuban sources. He followed this up by excluding the FBI's Cuban experts and supervisors in the bureau's own Cuba Section of the Domestic Intelligence Division from any investigation into Oswald's Mexico City activities. The director focused the probe away from Mexico and the Caribbean to the Soviet Union. Investigation into Oswald's political activities and associations was turned over to the bureau's Soviet experts.

In concert with the FBI, CIA Langley pulled the plug on an honest investigation into any Cuban aspects of the Kennedy assassination. In the CIA's case, the process was more indirect and devious, but the end result was same. Initially, the CIA's deputy director of plans, Richard Helms, appointed John Whitten to undertake the agency's in-house investigation into the assassination. Whitten was a senior career officer with twenty-three years in the clandestine service. In 1963 he was the head of WH-3, the agency's designation for the Western Hemisphere Branch that comprised Mexico and the Caribbean. The WH-3 head had a staff of thirty officers and about an equal number of clerical staff. What Whitten did not suspect at the time was that Helms and the chief of the CIA's Counterintelligence Branch, James Jesus Angleton, had set him up for failure. There is good reason to believe that Hoover was part of an interagency scheme to thwart any good faith investigation into the suspicious machinations surrounding the activities of the CIA's Mexico City station.

Theoretically, Whitten had the experienced area professionals, staff, and informers to conduct a sweeping investigation into Oswald's activities in Mexico City, but during the short time that Whitten was in charge of the investigation he ran into a stone wall. The FBI deluged his branch with thousands of reports containing bits and fragments of witness testimony that required laborious and time-consuming name checks. Whitten characterized most of the FBI information as "weirdo stuff." None of this mountain of paper contained vital information that was critical to any legitimate probe into the assassination. For example, Whitten knew nothing of Oswald's alleged pro-Castro activities in New Orleans during the summer of 1963, Oswald's so-called Historic Diary with insights into his years in the Soviet Union, or the FBI's assertion that JFK's charged assailant had attempted to take the life of General Edwin Walker. Whitten knew none of this until, at Katzenbach's December 6 invitation, he was allowed to read CD 1. By that time Helms and Angleton were preparing to pull the investigation out from under him.

In the chain of command for WH-3, COS Win Scott was under Whitten and, in the bureaucratic scheme of things, expected to report directly to Whitten. But Scott, Whitten's subordinate, never told him about Oswald's contacts with the Cuban and Soviet embassies until the day Kennedy was assassinated. Equally remarkable was the fact that Whitten had never heard of Lee Harvey Oswald until November 22, 1963, even though the CIA had a restricted 201 pre assassination file on Oswald held by the Counterintelligence/Special Investigative Group, indicating that this branch of the CIA confined to sensitive counterintelligence operations may have had a special interest in former marine PFC Lee Harvey Oswald."

(5) The Warren Report: Part 2, CBS Television (26th June, 1967)

Walter Cronkite: The most persuasive critic of the single-bullet theory is the man who might be expected to know best, the victim himself, Texas Governor John Connally. Although he accepts the Warren Report's conclusion, that Oswald did all the shooting, he has never believed that the first bullet could have hit both the President and himself.

John Connally:The only way that I could ever reconcile my memory of what happened and what occurred, with respect to the one bullet theory, is that it had to be the second bullet that might have hit us both.

Eddie Barker: Do you believe, Governor Connally, that the first bullet could have missed, the second one hit both of you, and the third one hit President Kennedy?

John Connally: That's possible. That's possible. Now, the best witness I know doesn't believe that.

Eddie Barker: Who is the best witness you know?

John Connally: Nellie was there, and she saw it. She believes the first bullet hit him, because she saw him after he was hit. She thinks the second bullet hit me, and the third bullet hit him.

Nellie Connally: The first sound, the first shot, I heard, and turned and looked right into the President's face. He was clutching his throat, and just slumped down. He just had a - a look of nothingness on his face. He didn't say anything. But that was the first shot.

The second shot, that hit John - well, of course, I could see him covered with - with blood, and his - his reaction to a second shot. The third shot, even though I didn't see the President, I felt the matter all over me, and I could see it all over the car.

So I'll just have to say that I think there were three shots, and that I had a reaction to three shots. And - that's just what I believe.

John Connally: Beyond any question, and I'll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me.

Now, so far as I'm concerned, all I can say with any finality is that if there is - if the single-bullet theory is correct, then it had to be the second bullet that hit President Kennedy and me.

(6) Leo Janos, The Atlantic Magazine (July 1973)

During coffee, the talk turned to President Kennedy, and Johnson expressed his belief that the assassination in Dallas had been part of a conspiracy. "I never believed that Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger." Johnson said that when he had taken office he found that "we had been operating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean." A year or so before Kennedy's death a CIA-backed assassination team had been picked up in Havana. Johnson speculated that Dallas had been a retaliation for this thwarted attempt, although he couldn't prove it. "After the Warren Commission reported in, I asked Ramsey Clark [then Attorney General] to quietly look into the whole thing. Only two weeks later he reported back that he couldn't find anything new." Disgust tinged Johnson's voice as the conversation came to an end. "I thought I had appointed Tom Clark's son - I was wrong."

(7) Ron Kessler, Washington Post (21st January, 1975)

The son of the late House Majority Leader Boggs has told the Washington Post that the FBI leaked to his father damaging material on the personal lives of the critics of its investigation into John F. Kennedy's assassination.

Thomas Hale Boggs, Jr. said his father, who was a member of the Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination and its handling by the FBI, was given the material in an apparent attempt to discredit the critics of the Warren Commission.

The material, which Thomas Boggs made available, includes photographs of sexual activity and reports on alleged communist affiliations of some authors of articles and books on the assassination.

(8) Bernard Fensterwald, Assassination of JFK: Coincidence or Conspiracy (1974)

"You have got to do everything on earth to establish the facts one way or the other. And without doing that, why everything concerned, including every one of us is doing a very grave disservice. Thus House Majority Leader Hale Boggs delivered an admonishment of sorts to his Warren Commission colleagues on January 27, 1964. Along with Senator Richard Russell, and to a lesser degree, Senator John Sherman Cooper, Congressman Boggs served as a beacon of skepticism and probity in trying to fend off the FBI and CIA's efforts to "shade" and indeed manipulate the findings of the Warren Commission.

Like Russell, Boggs was, very simply, a strong doubter. Several years after his death in 1972, a colleague of his wife Lindy (who was elected to fill her late husband's seat in the Congress) recalled Mrs. Boggs remarking, "Hale felt very, very torn during his work [on the Commission] ... he wished he had never been on it and wished he'd never signed it [the Warren Report]." A former aide to the late House Majority Leader has recently recalled, "Hale always returned to one thing: Hoover lied his eyes out to the Commission - on Oswald, on Ruby, on their friends, the bullets, the gun, you name it... "

Almost from the beginning, Congressman Boggs had been suspicious over the FBI and CIA's reluctance to provide hard information when the Commission's probe turned to certain areas, such as allegations that Oswald may have been an undercover operative of some sort. When the Commission sought to disprove the growing suspicion that Oswald had once worked for the FBI, Boggs was outraged that the only proof of denial that the FBI offered was a brief statement of disclaimer by J. Edgar Hoover. It was Hale Boggs who drew an admission from Allen Dulles that the CIA's record of employing someone like Oswald might be so heavily coded that the verification of his service would be almost impossible for outside investigators to establish...

Congressman Boggs had been the Commission's leading proponent for devoting more investigative resources to probing the connections of Jack Ruby. With an early recognition that "the most difficult aspect of this is the Ruby aspect," Boggs had wanted an increased effort made to investigate the accused assassin's murderer.

Boggs was perhaps the first person to recognize something which numerous Warren Commission critics would write about in future years: the strange variations and dissimilarities to be found in Lee Harvey Oswald's correspondence during 1960 to 1963. Some critics have advanced the theory that some of Oswald's letters - particularly correspondence to the American Embassy in Moscow, and later, to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee - may have been "planted" documents written by someone else. In 1975 and 1976, the investigations of the Senate Intelligence Committee and other Congressional groups disclosed that such uses of fabricated correspondence had been a recurring tool of the FBI's secret domestic COINTELPRO [Counter Intelligence] program as well as other intelligence operations. In any event, Warren Commission member Boggs and Commission General Counsel Lee Rankin had early on discussed such an idea:

"Rankin: They [the Fair Play For Cuba Committee] denied he was a member and also he wrote to them and tried to establish as one of the letters indicate, a new branch there in New Orleans, the Fair Play For Cuba.

Boggs: That letter has caused me a lot of trouble. It is a much more literate and polished communication than any of his other writing."

It is also known Boggs felt that because of the lack of adequate material from the FBI and CIA the Commission members were poorly prepared for the examination of witnesses. According to a former Boggs staffer, the Congressman felt that lack of adequate file preparation and the sometimes erratic scheduling of Commission sessions served to prevent those same sessions from being adequately substantive. Consequently, Boggs cut down his participation in these sessions as the investigation stretched on through 1964...

On April 5, 1971, House Majority Leader Hale Boggs took the floor of the House to deliver a speech that created a major stir in Washington for several weeks. Declaring that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was incompetent and senile, and charging that the FBI had, under Hoover's most recent years adopted "the tactics of the Soviet Union and Hitler's Gestapo"; Boggs demanded Hoover's immediate resignation. Boggs also charged that he had discovered that certain FBI agents had tapped his own telephone as well as the phones of certain other members of the House and Senate. In his emotional House speech, Boggs went on to say Attorney General Mitchell says he is a law and order man. If law and order means the suppression of the Bill of Rights . . . then I say "God help us." As the Washington Post noted, "The Louisiana Democrat's speech was the harshest criticism of Hoover ever heard in the House . . . It was the first attack on Hoover by any member of the House leadership."

At the time, Boggs' startling speech created a sensation in Washington. Observers were uncertain as to his exact motivations in demanding Hoover's resignation, and there was an immediate critical reaction from Hoover's various defenders. It has been reported that sources within the FBI and the Attorney General's office began spreading stories that Boggs was a hopeless alcoholic. However, it was not until almost four years later that the motivation behind Boggs' outburst came into clearer focus.

(9) Gaëtane Morin, Le Parisien (21 November 2013)

It is "the most beautiful memory" of his life. When Valéry Giscard d'Estaing delves into his memory to recall his meeting with President Kennedy in 1962, the twenty minutes he was supposed to devote to the interview expand, time passes without us noticing....

"I took advantage of a state visit to the United States in 1976 to pay tribute to JFK. I went to Arlington Cemetery, where he is buried.

I place a bouquet of violets on his grave, the flower of remembrance. Neither wreath nor ribbon: this is not the statesman speaking, my approach is personal.

During this official trip, I was welcomed by President Gerald Ford, who was one of the members of the Warren Commission, tasked with shedding light on the Kennedy assassination.

As we drive toward Mount Vernon, the former home of President George Washington, I ask him if he has formed an opinion on the matter.

He replied: "Yes. We have concluded that this assassination was planned. There was a conspiracy. But we have not been able to identify which organization ordered it."

I share this opinion. I became certain of it when, three years after this interview, I discussed this question with a very important oil entrepreneur from New Orleans with whom I was hunting in Scotland.

Naively, I asked him, "Do you know who assassinated Kennedy?" He answered without blinking, "Yes." It wasn't a lone, crazy gunman who killed the President of the United States.

(10) John S. Cooper, interviewed by Morris Wolff for his book, Lucky Conversations: Visits With the Most Prominent People of the 20th Century (2021) page 112

They have it all wrong. They refuse to look at the facts. The forensics are right there. One bullet came in from the front, and the President grabbed his neck, and his head shot back in the open limousine. The car had slowed down in front of the Texas School Depository. The next shot came in from the back, from a window on the 7th floor, the top floor of the Book Depository building on Dealey Plaza. A third shot came from behind the motorcade, jerking his head backward as he slowly passed the area. It was the shot fired by Lee Harvey Oswald, one of two or three killers. At least two were active that day, one from in front and the second from the back. The forensics clearly show there were at least two separate shooters, and they were standing in different places, one from the grassy knoll and one high in the office building. Our new President, Lyndon Baines Johnson, now wants to cover up and move on. I want to delay and get all the facts. They are covering the facts and putting their collective heads in the sand. LBJ pretends to give me the green light to press forward with the investigation. But he is secretly telling the others to bring the hearings to a quick close…. They want to bury the truth under a pile of stones. I think Lyndon Baines Johnson was involved in the planning and execution of Kennedy's death."