John McCloy

John Jay McCloy was born in Philadelphia, on 31st March, 1895. He graduated from Amherst College in 1919, and Harvard Law School in 1921. McCloy joined the leading law firm, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft. George Wickersham was a former attorney general and Henry W. Taft was the brother of President William Howard Taft.

In 1924 McCloy joined Cravath, Henderson & de Gersdorff. The three senior partners were Paul Cravath, Hoyt Moore and Carl de Gersdorff. During this period he became friendly with W. Averell Harriman and Robert A. Lovett. In 1927 McCloy was sent to establish an office in Milan. Over the next few years he traveled throughout Italy, France and Germany on business. According to Anton Chaitkin (George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography) McCloy worked as an advisor to the fascist government of Benito Mussolini.

McCloy developed the view that German Reparations as a result of the First World War were both unwise and unfair. According to McCloy: "Practically every merchant bank and Wall Street firm, from J. P. Morgan and Brown Brothers on down, was over there (Germany) picking up loans. We were all very European in our outlook, and our goal was to see it rebuilt." McCloy argued that if this did not happen, Germany would be taken over by the communists, who were getting support from the Soviet Union.

In his dealings with Germany, McCloy worked closely with Paul M. Warburg, the founder of M. M. Warburg in Hamburg, who argued that the "United States should throw open its doors to European imports and pay for them with the gold the Allies had used to pay for U.S. war material". Warburg argued that this strategy would result in New York becoming the world's financial and commercial centre.

In July, 1929, McCloy became a partner in the Cravath, Henderson & de Gersdorff law firm. He was rewarded with a salary of $15,000. This was a time when fewer than 6% of Americans earned more than $3,000 a year. McCloy did not put his money into stocks and shares and was unaffected by the 1929 Wall Street Crash.

McCloy's brother-in-law, Lewis W. Douglas, was a member of the Democratic Party and in March, 1933, he was appointed Director of the Budget by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, Douglas became convinced that the New Deal had been infiltrated by communists. Douglas told McCloy that "He (Roosevelt) is surrounded with the young Harvard Law School group, all of whom are communists."

Douglas also believed that the New Deal was part of a Jewish conspiracy to destroy the capitalist system. He talked about the "Hebraic influence" and claimed that "most of the bad things which it (the administration) has done can be traced to it. as a race they seem to lack the quality of facing an issue squarely." As a result of his beliefs, Douglas resigned from the government in August, 1934.

According to his biographer, Kai Bird (The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment), McCloy shared these views: "He (McCloy) was a man of his times and class. And in Wall Street during the 1930s, few men challenged the notion that, as a rule, Jews were socially pushy and arrogant, particularly when placed in positions of power and influence."

However, McCloy remained close to Jews such as James Warburg. He also worked as an adviser to Franklin D. Roosevelt until 1934. The following year, Warburg wrote a book where he suggested that the 1936 election would come down to a choice between dictatorship or democracy.

In 1936 the Republican Party nominated Alfred Landon as their presidential candidate. Landon's first choice as a running mate, Lewis W. Douglas, was vetoed by party leaders. McCloy remained a party loyalist, and supported Landon against Roosevelt.

McCloy continued to specialize in German cases and in 1936 Mccloy traveled to Berlin where he had a meeting with Rudolf Hess. This was followed by McCloy sharing a box with with Adolf Hitler and Herman Goering at the Berlin Olympics. McCloy's law firm also represented I.G. Farben and its affiliates during this period.

In 1941 Henry L. Stimson selected McCloy to become assistant secretary of war. In 1942 General George C. Marshall sent McCloy to "check out" a new officer working in the War Plans Division. His name was Dwight D. Eisenhower. McCloy later recalled: "So I went down to meet this man; I don't think I ever told him that I had been sent to spy on him." It was the beginning of a long friendship.

In December, 1941, Stimson put McCloy in charge of dealing with what he called the "West Coast security problem". This had been brought to Stimson's attention by Congressman Leland M. Ford of Los Angeles who had called for "all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in inland concentration camps". McCloy held a meeting with J. Edgar Hoover and Attorney General Francis Biddle on 1st February, 1942 about this issue. Biddle argued that the Justice Department would have nothing to do with any interference with citizens, "whether they are Japanese or not". McCloy replied, "the Constitution is just a scrap of paper to me."

McCloy also got support from Earl Warren, the Attorney General of the State of California. He argued that all Japanese-Americans should be interned. However, Henry L. Stimson, like Francis Biddle, had his doubts about the wisdom of taking this action. However, on 19th February, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the construction of relocation camps for Japanese Americans being moved from their homes.

Over the next few months ten permanent camps were constructed to house more than 110,000 Japanese Americans that had been removed from security areas. These people were deprived of their homes, their jobs and their constitutional and legal rights. Earl Warren later confessed: "I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens. Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken."

The American Civil Liberties Union called the internment of Japanese-Americans as the "greatest deprivation of civil liberties by government in this country since slavery." As Kai Bird (The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment) has pointed out: "More than any individual, McCloy was responsible for the decision, since the president had delegated the matter to him through Stimson... Why, then, did McCloy become an advocate of mass evacuation? One answer is simple racism."

Mitsuye Endo, a Nisei, petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that detention in a relocation camp was unlawful. In December 1944 the Supreme Court ruled in her favour and over the next few weeks the Japanese Americans in the camps returned to their homes in California.

On 9th April 1944, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, managed to escape from Auschwitz. The two men spent eleven days walking and hiding before they got back to Slovakia. Vrba and Wetzler made contact with the local Jewish Council. They provided details of the Holocaust that was taking place in Eastern Europe. They also gave an estimate of the number of Jews killed in Auschwitz between June 1942 and April 1944: about 1.75 million.

On 29th June, 1944, the 32-page Vrba-Wetzler Report was sent to John McCloy. Attached to it was a note requesting the bombing of vital sections of the rail lines that transported the Jews to Auschwitz. McCloy investigated the request and then told his personal aide, Colonel Al Gerhardt, to "kill" the matter.

McCoy received several requests to take military action against the death camps. He always sent the following letter: "The War Department is of the opinion that the suggested air operation is impracticable. It could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations and would in any case be of such very doubtful efficacy that it would not amount to a practical project."

This was untrue. Long-range American bombers stationed in Italy had been flying over Auschwitz and the neighbouring I. G. Farben petrochemical plant since April, 1944. The American Air Force were also bombing Germany's synthetic-fuels plants to regions very close to the death camps. In fact, in August 1944, the Monowitz camp, part of the Auschwitz complex, was bombed by accident.

Benjamin Akzin, one of McCloy's aides, disagreed with McCloy's decision. He pointed out that if the transport links and the death camps were bombed, it would force the Germans to spend considerable time and resources to reconstruct the gas chambers. Akzin added that it was not only an important military target but a "matter of principle".

In August, 1944, Leon Kubowitzki, an official with the World Jewish Congress in New York, passed on an appeal from Ernest Frischer, a member of the Czech government-in-exile, to take military action against the concentration camps. McCloy rejected the idea as it would require "diversion of considerable air support" and "even if practicable, might provoke even more vindictive action by the Germans."

Nahum Goldman, president of the World Jewish Congress, also had a meeting with McCloy. Goldman was later to say: "McCloy indicated to me that, although the Americans were reluctant about my proposal, they might agree to it, though any decision as to the targets of bombardments in Europe was in the hands of the British". Once again, this was untrue. In fact, Winston Churchill had already ordered the bombing of Auschwitz. However, Archibald Sinclair, the British Secretary of State for Air, pointed out that "the distance of Silesia (where Auschwitz was located) from our bases entirely rules out our doing anything of the kind."

In November, 1944, John Pehle, the executive director of the War Refugee Board, wrote to McCloy to change his mind on this issue. This time he enclosed a recent New York Times article on the British bombing of a German prison camp in France where a hundred French resistance fighters condemned to death had escaped in the aftermath of the bombing." After consulting with Lieutenant General John Hull, the chief of Operations Division of the War Department, McCloy replied that "the results obtained would not justify the high losses likely to result from such a mission."

After the war McCloy was invited by Nelson Rockefeller to join the family law firm. He accepted the offer and the firm became known as Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy. The law firm's most important client was the Rockefeller family's bank, Chase Manhattan. As John D. Rockefeller Jr. told his personal lawyer, Thomas M. Debevoise, "McCloy knows so many people in government circles... that he might be in the way to get information in various quarters about the matter without seeking it, or revealing his hand." McCloy's main task involved lobbying for the gas and oil industry.

The family's main concern was the threat posed against their interests in Standard Oil of California. John D. Rockefeller Jr. owned almost 6 per cent of the stock of the company, making him the single largest shareholder. In 1946 Harold Ickes claimed that Rockefeller was violating the terms of the 1911 dissolution decree. Two other anti-trust lawyers, Abe Fortas and Thurman Arnold, joined forces with Ickes to petition the Justice Department to investigate the matter. John J. McCloy, was asked to sort the matter out and by the autumn of 1946, he had persuaded Ickes, Fortas and Arnold to drop the matter.

In 1947 McCloy was appointed president of the World Bank. However, in 1949 he replaced Lucius Clay, as High Commissioner for Germany. Soon after taking office McCloy became embroiled in the infamous case of Klaus Barbie, the man who had been Gestapo chief in Lyon during the war.

On 7th June 1943, Barbie had captured René Hardy, a member of the French Resistance who had successfully carried out several acts of sabotage against the Germans. Barbie eventually obtained enough information to arrest three of the most important leaders of the French Resistance, Jean Moulin, Pierre Brossolette and Charles Delestraint. Moulin and Brossolette both died while being tortured and Delestraint was sent to Dachau where he was killed near the end of the war.

As Allied troops approached Lyons in September 1944, Barbie destroyed Gestapo records and killed hundreds of Frenchmen who had first-hand knowledge of his brutal interrogation methods. This included twenty double-agents who had been supplying his with information about the French Resistance.

Barbie fled back to Nazi Germany where he had been recruited by the US Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC). Barbie impressed his American handlers by infiltrating the Bavarian branch of the Communist Party. According to the CIC Barbie's "value as an informant infinitely outweighs any use he may have in prison."

René Hardy was tried for treason in 1950. Both the prosecution and the defence teams wanted Barbie to testify. At this time McCloy was concerned about the growth of communism in Bavaria and valued the role played by Barbie in this struggle. Therefore he decided to reject the requests being made by the French authorities to hand over Barbie. During the trial, Hardy's defence lawyer exposed what was happening by announcing in court that it was "scandalous that the U.S. military authorities in Germany were protecting Barbie from extradition for security reasons."

Barbie was in fact in hiding in a CIC safe house in the American Zone in Germany. McCloy denied any knowledge of where Barbie was and instead announced that the case was under investigation. McCloy was informed by CIC that: "This entire Hardy-Barbie affair is being pushed as a political issue by left-wing elements in France. No strong effort has been made by the French to obtain Barbie because of the political embarrassment his testimony might cause certain high French officials." In other words, Barbie had information that would show how prominent French politicians who during the war had collaborated with the Gestapo. The American government also were worried about what Barbie might say about his involvement with the CIC in Germany.

On 8th May, 1950, René Hardy was acquitted. As Kai Bird pointed out (The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment): " The enraged French public blamed the Americans for not allowing Barbie, the star witness against Hardy, to be extradited from Germany. By the end of May, under pressure from French resistance veterans, the French government had once again requested Barbie's apprehension."

McCloy was now in a difficult position. He was reluctant to admit that the CIC was employing an accused war criminal. In fact, it was more serious than that. According to one CIC document, Klaus Barbie had "personally directed CIC's counterintelligence operations aimed at infiltrating French intelligence." CIC told McCloy that "a complete disclosure by Barbie to the French of his activities on behalf of CIC would... furnish the French with evidence that we had been directing intelligence operations against them."

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1950 McCloy told the French that "continuous efforts to locate Barbie are being made". In reality, no search of any kind was conducted as they knew where he was living. In fact, he continued to draw a CIC salary during this period.

In March 1950, McCloy was given the task of appointing a new head of the West German Secret Service. After discussing the matter with Frank Wisner of the CIA, McCloy decided on Reinhard Gehlen, the Nazi war criminal. This resulted in protests from the Soviet Union government who wanted to try Gehlen for war crimes.

During the Second World War Gehlen served Adolf Hitler as head of military intelligence for the Eastern Front. It was in this post he had created a right-wing group made up of anti-Soviet Ukrainians and other Slavic nationalists into small armies and guerrilla units to fight the Soviets. The group carried out some of the most extreme atrocities that took place during the war. Gehlen was also responsible for a brutal interrogation program of Soviet prisoners of war.

On May 22, 1945, Major General Gehlen surrendered to the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) in Bavaria. In August he was interrogated by Office of Strategic Services (OSS) officers headed by Frank Wisner. According to one source, Gehlen was able to identify several OSS officers who were secret members of the American Communist Party.

It was decided to use Gehlen to collect intelligence on the Soviet Union from a network of anti-communist informants in Eastern Europe. This group became known as the Gehlen Organization. In 1949 Gehlen signed a contract with the CIA, reportedly for a sum of $5 million a year, which allowed him to expand his activities into political, economic, and technological espionage.

Gehlen recruited large numbers of former members of the SS and the Gestapo. This included Franz Six, who had led Einsatzguppen mobile killing squads on the Eastern Front. The Gehlen Organization was also used to help Nazi war criminals escape to South America. This included Klaus Barbie who was smuggled out of Germany in March, 1951 and given a new life in Bolivia. It has been alleged that in some cases the CIA helped Gehlen to get these men to safety.

In 1950 McCloy began receiving communications from people in Germany calling on him to release Nazis from prison. This pressure came from senior figures in the new West German government. Two figures they were especially concerned about were German industrialists, Alfried Krupp and Friedrich Flick, who had both been convicted of serious war crimes at Nuremberg.

Alfried Krupp and his father Gustav Krupp ran Friedrich Krupp AG, Germany's largest armaments company. Krupp and his father were initially hostile to the Nazi Party. However, in 1930 they were persuaded by Hjalmar Schacht that Adolf Hitler would destroy the trade unions and the political left in Germany. Schacht also pointed out that a Hitler government would considerably increase expenditure on armaments. In 1933 Krupp joined the Schutzstaffel (SS).

During the Second World War Krupp ensured that a continuous supply of his firm's tanks, munitions and armaments reached the German Army. He was also responsible for moving factories from occupied countries back to Germany where they were rebuilt by the Krupp company.

Krupp also built factories in German occupied countries and used the labour of over 100,000 inmates of concentration camps. This included a fuse factory inside Auschwitz. Inmates were also moved to Silesia to build a howitzer factory. It is estimated that around 70,000 of those working for Krupp died as a result of the methods employed by the guards of the camps.

In 1943 Adolf Hitler appointed Alfried Krupp as Minister of the War Economy. Later that year the SS gave him permission to employ 45,000 Russian civilians as forced labour in his steel factories as well as 120,000 prisoners of war in his coalmines.

Arrested by the Canadian Army in 1945 Alfried Krupp was tried as a war criminal at Nuremberg. He was accused of plundering occupied territories and being responsible for the barbaric treatment of prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates. Documents showed that Krupp initiated the request for slave labour and signed detailed contracts with the SS, giving them responsibility for inflicting punishment on the workers.

Krupp was eventually found guilty of being a major war criminal and sentenced to twelve years in prison and had all his wealth and property confiscated. Convicted and imprisoned with him were nine members of the Friedrich Krupp AG board of directors. However, Gustav Krupp, the former head of the company, was considered too old to stand trial and was released from custody.

By 1950 the United States was involved in fighting the Cold War. In June of that year, North Korean troops invaded South Korea. It was believed that German steel was needed for armaments for the Korean War and in October, McCloy lifted the 11 million ton limitation on German steel production. McCloy also began pardoning German industrialists who had been convicted at Nuremberg. This included Fritz Ter Meer, the senior executive of I. G. Farben, the company that produced Zyklon B poison for the gas chambers. He was also Hitler's Commissioner of for Armament and War Production for the chemical industry during the war.

McCloy was also concerned about the increasing power of the left-wing, anti-rearmament, Social Democratic Party (SDP). The popularity of the conservative government led by Konrad Adenauer was in decline and a public opinion poll in 1950 showed it only had 24% of the vote, while support for the SDP had risen to 40%. On 5th December, 1950, Adenauer wrote McCloy a letter urging clemency for Krupp. Hermann Abs, one of Hitler's personal bankers, who surprisingly was never tried as a war criminal at Nuremberg, also began campaigning for the release of German industrialists in prison.

In January, 1951, McCloy announced that Alfried Krupp and eight members of his board of directors who had been convicted with him, were to be released. His property, valued at around 45 million, and his numerous companies were also restored to him.

Others that McCloy decided to free included Friedrich Flick, one of the main financial supporters of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). During the Second World War Flick became extremely wealthy by using 48,000 slave labourers from SS concentration camps in his various industrial enterprises. It is estimated that 80 per cent of these workers died as a result of the way they were treated during the war. His property was restored to him and like Krupp became one of the richest men in Germany.

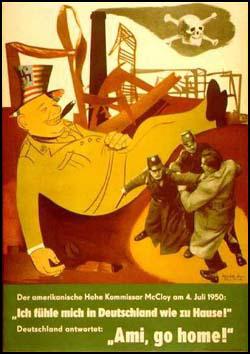

McCloy's decision was very controversial. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to McCloy to ask: "Why are we freeing so many Nazis? The Washington Post published a Herb Block cartoon depicting a smiling McCloy opening Krupp's cell door, while in the background Joseph Stalin is shown taking a photograph of the event. Telford Taylor, who took part in the prosecution of the Nazi war criminals wrote: "Wittingly or not, Mr. McCloy has dealt a blow to the principles of international law and concepts of humanity for which we fought the war."

Rumours began circulating that McCloy had been bribed by the Krupp's American lawyer, Earl J. Carroll. According to one magazine: "The terms of Carroll's employment were simple. He was to get Krupp out of prison and get his property restored. The fee was to be 5 per cent of everything he could recover. Carroll got Krupp out and his fortune returned, receiving for his five-year job a fee of, roughly, $25 million."

McCloy rejected these claims and told the journalist, William Manchester: "There's not a goddamn word of truth in the charge that Krupp's release was inspired by the outbreak of the Korean War. No lawyer told me what to do, and it wasn't political. It was a matter of my conscience."

After leaving Germany in 1953 McCloy became chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank (1953-60) and the Ford Foundation (1958-65). He also continued to work for Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy. The company was owned by the Rockefeller family and therefore McCloy became involved in lobbying for the gas and oil industry.

McCloy remained close to Dwight D. Eisenhower and according to Kai Bird (The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment): "On at least one occasion, in February 1954, he (McCloy) used a Chase National Bank plane to ferry himself and the rest of Ike's gang down from New York in order to keep a golf date with the president at the Augusta National range."

It was Eisenhower who first introduced McCloy to Sid Richardson and Clint Murchison. Soon afterwards, Chase Manhattan Bank began providing the men with low-interest loans. In 1954 McCloy worked with Richardson, Murchison and Robert R. Young in order to take control of the New York Central Railroad Company. The activities of these men caused a great deal of concern and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) eventually held hearings about what was described as "highly improper" behaviour. The takeover was a disaster and Young committed suicide and New York Central eventually went bankrupt.

In 1950 Dwight D. Eisenhower had purchased a small farm for $24,000. According to Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson (The Case Against Congress), several oil millionaires, including W. Alton Jones, B. B. Byers and George E. Allen, began acquiring neighbouring land for Eisenhower. Jonathan Kwitny (Endless Enemies) has argued that over the next few years Eisenhower's land became worth over $1 million: "Most of the difference represented the gifts of Texas oil executives connected to Rockefeller oil interests. The oilmen acquired surrounding land for Eisenhower under dummy names, filled it with livestock and big, modern barns, paid for extensive renovations to the Eisenhower house, and even wrote out checks to pay the hired help."

In 1956 there was an attempt to end all federal price control over natural gas. Sam Rayburn played an important role in getting it through the House of Representatives. This is not surprising as according to John Connally, he alone had been responsible for a million and a half dollars of lobbying.

Paul Douglas and William Langer led the fight against the bill. Their campaigned was helped by a speech by Francis Case of South Dakota. Up until this time Case had been a supporter of the bill. However, he announced that he had been offered a $25,000 bribe by the Superior Oil Company to guarantee his vote. As a man of principal, he thought he should announce this fact to the Senate.

Lyndon B. Johnson responded by claiming that Case had himself come under pressure to make this statement by people who wanted to retain federal price controls. Johnson argued: “In all my twenty-five years in Washington I have never seen a campaign of intimidation equal to the campaign put on by the opponents of this bill.” Johnson pushed on with the bill and it was eventually passed by 53 votes to 38. However, three days later, Dwight D. Eisenhower, vetoed the bill on grounds of immoral lobbying. Eisenhower confided in his diary that this had been “the most flagrant kind of lobbying that has been brought to my attention”. He added that there was a “great stench around the passing of this bill” and the people involved were “so arrogant and so much in defiance of acceptable standards of propriety as to risk creating doubt among the American people concerning the integrity of governmental processes”.

The decision by Dwight D. Eisenhower to veto this bill angered the oil industry. Once again Sid Richardson and Clint Murchison began negotiations with Eisenhower. In June, 1957, Eisenhower agreed to appoint their man, Robert B. Anderson, as his Secretary of the Treasury. According to Robert Sherrill in his book, The Accidental President: "A few weeks later Anderson was appointed to a cabinet committee to "study" the oil import situation; out of this study came the present-day program which benefits the major oil companies, the international oil giants primarily, by about one billion dollars a year."

According to Jonathan Kwitny (Endless Enemies) from 1955 to 1963, Richardson, Murchison, and Rockefeller interests (arranged by John McCloy) and the International Basic Economy Corporation (100% owned by the Rockefeller family) gave "away a $900,000 slice of their Texas-Louisiana oil property" to Robert B. Anderson, Eisenhower's Secretary of the Treasury.

Lyndon B. Johnson discussed the possibility of appointing John McCloy to the Warren Commission in a telephone conversation with Abe Fortas on 29th November, 1963. When Johnson mentioned his name Fortas replied: “I think that’d be great. He’s a wonderful man and a very dear friend of mine. I’m devoted to him.”

McCloy was an early opponent of the Lee Harvey Oswald as the lone-gunman theory. At the Warren Commission meeting on 16th December, 1963, Allen Dulles gave out copies of a ten-year old book that looked at the seven previous attempts on the lives of various presidents. The author argued that presidential assassins typically are misfits and loners. Dulles told his colleagues, “…you’ll find a pattern running through here that I think we’ll find in this present case.” McCloy replied: “The Lincoln assassination was a plot”.

McCloy also told his wife he was having difficulty with the lone-gunman theory. He also informed her that he thought Oswald was having a relationship with the intelligence services before the assassination. McCloy commented that he thought it was “pretty suspicious” that Oswald had found it so easy to obtain an exit visa from the Soviet Union for his Russian wife, Marina Oswald. McCloy told his wife that he had heard “a very realistic rumor” that Oswald was not a genuine defector and that he was sent to the Soviet Union by the CIA.

McCloy was also concerned about the workings on the Warren Commission. They met only twice in December, 1963. The third meeting did not take place until the third week of January. John McCone reported to Lyndon B. Johnson on 9th January that McCloy had complained the previous day about this lack of urgency. McCloy told McCone that he feared the “trails of evidence will be lost” and that they have been interviewing witnesses soon after the assassination. In fact, the commission did not get the chance to question witnesses until nearly six months after the event.

McCloy became concerned about the nature of Kennedy’s wounds. At one meeting he said: “Let’s find out about these wounds, it is just as confusing now as could be. It left my mind muddy as to what really did happen… Why did the FBI report come out with something which isn’t consistent with the autopsy.” At this stage McCloy suspected that at least two men fired at John F. Kennedy. He said he wanted to visit Dealey Plaza “to see if it is humanly possible for him (Kennedy) to have been hit in the front.”

It also emerged that McCloy was highly critical of the FBI report on the assassination. He blamed it on the report being “put together very fast”. What McCloy did not know was that J. Edgar Hoover was withholding evidence from the Warren Commission. Nor was he aware of the Hoover telephone call to LBJ on 24th November, 1963, when he said: “The thing I am most concerned about… is having something issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassination.”

At a meeting with J. Lee Rankin on 22nd January, 1964, McCloy was told that according to the Texas attorney general, Oswald had been an undercover agent of the FBI since September 1962. According to Rankin, his agent number was 179 and was being paid $200 a month.

McCloy was also in communication with the Time-Life executive, C. D. Jackson, about the Zapruder film. Jackson sent McCloy blown-up transparencies of the film that revealed that John F. Kennedy and Connally had been hit by different bullets. McCloy also questioned Connally’s doctor at the hospital, who was also of the opinion that he had been hit by a separate bullet from Kennedy.

In an interview he gave on 3rd July, 1967, McCloy said: “I think there’s one thing I would do over again. I would insist on those photographs and the X-rays having being produced before us.” During the investigation members of the Warren Commission were told by Earl Warren that the Kennedy family was blocking access to these photographs and X-rays.

McCloy initially dismissed the idea of the magic bullet but he was persuaded to change his mind. So much so, when Richard Russell, Thomas Hale Boggs and John Sherman Cooper said that they had “strong doubts” about the lone gunman theory, McCloy took the side of Gerald R. Ford and Allen Dulles. In fact, McCloy played the main role in persuading the three men to sign the Warren Commission report that they did not believe in.

During 1964 McCloy was also working for one of Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy law firm’s most important clients, M. A. Hanna Mining Company. McCloy had several meetings with Hanna’s chief executive officer, George M. Humphrey. The two men had been close friends since Humphrey was Eisenhower’s Treasury Secretary. Humphrey was very concerned about the company’s investment in Brazil. Hanna Mining was the largest producer of iron ore in the country. However, after João Goulart had become president in 1961, he began to talk about nationalizing the iron ore industry.

Goulart was a wealthy landowner who was opposed to communism. However, he was in favour of the redistribution of wealth in Brazil. As minister of labour he had increased the minimum wage by 100%. Colonel Vernon Walters, the US military attaché in Brazil, described Goulart as “basically a good man with a guilty conscience for being rich.”

The CIA began to make plans for overthrowing Goulart. A psychological warfare program approved by Henry Kissinger, at the request of telecom giant ITT during his chair of the 40 Committee, sent U.S. PSYOPS disinformation teams to spread fabricated rumors concerning Goulart.

McCloy was asked to set up a channel of communication between the CIA and Jack W. Burford, one of the senior executives of the Hanna Mining Company. In February, 1964, McCloy went to Brazil to hold secret negotiations with Goulart. However, Goulart rejected the deal offered by Hanna Mining.

The following month Lyndon B. Johnson gave the go-ahead for the overthrow of João Goulart (Operation Brother Sam). Colonel Vernon Walters arranged for General Castello Branco to lead the coup. A US naval-carrier task force was ordered to station itself off the Brazilian coast. As it happens, the Brazilian generals did not need the help of the task force. Goulart’s forces were unwilling to defend the democratically elected government and he was forced to go into exile.

David Kaiser points out in his book, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War (2000) that Johnson’s actions was a return to Eisenhower’s foreign policy where democratically elected leaders in the third world were removed on behalf of American industrialists. As Kai Bird commented in The Chairman: John J. McCloy: “ The Johnson administration had made clear its willingness to use its muscle to support any regime whose anti-communist credentials were in good order.”

in 1975 McCloy established the McCloy Fund. The main purpose of this organization was to promote German-American relations. The initial funding came from German industrialists. In 1982, the chairman of the Krupp Foundation, Berthold Beitz, gave the McCloy Fund a $2 million grant.

Three years later, the president of Germany, Richard von Weizsacker, conferred honorary German citizenship on McCloy. He praised McCloy’s “human decency in helping the beaten enemy to recover” and his efforts to build “one of the free and prosperous countries in the world.” Weizsacker had good reason to be thankful to McCloy. His father was Ernst von Weizsacker, a leading official in Adolf Hitler’s government. He was found guilty of crimes against humanity at Nuremberg and sentenced to seven years. McCloy was the one who arranged for him to be released in 1950.

John McCloy developed a close relationship with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (Shah of Iran), who gained power in Iran during the Second World War. McCloy's legal firm, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy, provided legal counsel to Pahlavi. The Chase International Investment Corporation, which McCloy established in the 1950s, had several joint ventures in Iran.

McCloy was also chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank. Pahlavi had a personal account with the bank. So also did his private family trust, the Pahlavi Foundation. Kai Bird (The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment) has argued: "Each year, the bank handled some $2 billion in Iranian Eurodollar transactions, and throughout the 1970s Iran had at least $6 billion on deposit at various branches around the world." As one financial commentator pointed out: "Iran became the crown jewel of Chase's international banking portfolio."

In January 1978, mass demonstrations took place in Iran. McCloy became concerned that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi would be overthrown. This was a major problem as outstanding loans to the regime amounted to over $500 million. McCloy went to see Robert Bowie, deputy director of the CIA. Bowie, who had just returned from Iran, was convinced that the communist Tudeh Party was behind the protests and were guilty of manipulating the Fedayeen and Mujahadeen. Over the next few months, McCloy organized a campaign to persuade President Jimmy Carter to protect the regime. This included David Rockefeller, Nelson Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger making deputations to the administration.

Despite the fact that Iranian troops had killed over 10,000 demonstrators during the disturbances, on 12th December, 1978, President Jimmy Carter issued a statement saying: "I fully expect the Shah to maintain power in Iran... I think the predictions of doom and disaster that come from some sources have certainly not been realized at all. The Shah has our support and he also has our confidence." The following month Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled the country and on 1st February, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile to form a new government.

McCloy asked President Carter to allow the Shah to live in the United States. Carter refused because he had told by his diplomats in Iran that such a decision might encourage the embassy being stormed by mobs. As a result McCloy made preparations for the Shah to stay in the Bahamas. David Rockefeller arranged for his personal assistant at Chase Manhattan, Joseph V. Reed, to manage the Shah's finances.

Rockefeller also established the highly secret, Project Alpha. The main objective was to persuade Carter to provide a safe haven for Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (code-named "Eagle"). McCloy, Rockefeller and Kissinger were referred to as the "Triumvirate". Rockefeller used money from Chase Manhattan Bank to pay employees of Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy who worked on the project. Some of this money was used to persuade academics to write articles defending the record of Pahlavi. For example, George Lenczowski, professor emeritus at the University of California, was paid $40,000 to write a book with the "intention to answer the shah's critics".

Kissinger telephoned Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor to Carter, on 7th April, 1979, and berated the president for his emphasis on human rights, which he considered to be "amateurish" and "naive". Brzezinski suggested he talked directly to Jimmy Carter. Kissinger called Carter and arranged for him to meet David Rockefeller, two days later. Gerald Ford also contacted Carter and urged him to "stand by our friends".

McCloy, Rockefeller and Kissinger arranged for conservative journalists to mount an attack on Carter over this issue. On 19th April, George F. Will wrote about Carter and the Shah and said; "It is sad that an Administration that knows so much about morality has so little dignity."

On 19th April, Rosalynn Carter wrote in her diary: "We can't get away from Iran. Many people - Kissinger, David Rockefeller, Howard Baker, John McCloy, Gerald Ford - all are after Jimmy to bring the shah to the United States, but Jimmy says it's been too long, and anti-American and anti-shah sentiments have escalated so that he doesn't want to. Jimmy said he explained to all of them that the Iranians might kidnap our Americans who are still there."

McCloy had meetings with President Carter in the White House on 16th May and 12th June where he outlined his reasons for providing Mohammad Reza Pahlavi with sanctuary. Carter listened politely to his arguments but refused to change his mind.

During the summer of 1979 McCloy contacted Zbigniew Brzezinski, Cyrus Vance, Walter Mondale and Dean Rusk about the Shah being allowed to live in the United States. McCloy told them that Carter's refusal to provide sanctuary to an old U.S. ally was "ungentlemanly" and dismissed the idea that lives in Iran might be jeopardized. Vance later recalled that: "John (McCloy) is a very prolific letter writer. The morning mail often contained something from him about the Shah".

In July 1979, Mondale and Brzezinski told Jimmy Carter that they had changed their minds and now supported asylum for the Shah. Carter replied: "F*** the Shah. I'm not going to welcome him here when he has other places to go where he'll be safe." He added that despite the fact that "Kissinger, Rockefeller and McCloy had been waging a constant campaign on the subject" he did not want the Shah "here playing tennis while Americans in Teheran were being kidnapped or even killed."

McCloy then tried another tactic in order to destabilize Carter's administration. In September, a story was leaked that the CIA had "discovered" a Soviet combat brigade in Cuba. It was claimed that this violated the agreement reached during the Cuban Missile Crisis. McCloy, who had negotiated the agreement with Adlai Stevenson and the Soviets in 1962, knew this was not true. The agreement said that only those Soviet troops associated with the missiles had to leave the island. There was never a complete ban on all Soviet troops in Cuba. Therefore the presence of Soviet combat troops in Cuba was not a violation of the 1962 agreement.

In October, 1979, David Rockefeller's assistant, Joseph V. Reed, called the State Department and claimed that the Shah had cancer and needed immediate treatment in a U.S. medical facility. Cyrus Vance now told Carter that the Shah should be allowed in as a matter of "common decency". Carter's chief of staff, Hamilton Jordan, argued that if the Shah died outside the United States, Kissinger and his friends would say "that first you caused the Shah's downfall and now you've killed him." Carter replied: "What are you guys going to advise me to do if they overrun our embassy and take our people hostage?"

Faced with the now unanimous opposition of his closest advisers, the president reluctantly agreed to admit the Shah. He arrived at New York Hospital on 22nd October, 1979. Joseph V. Reed circulated a memo to McCloy and other members of Project Alpha: "Our mission impossible is completed. My applause is like thunder." Less than two weeks later, Iranian militants stormed the U.S. Embassy in Teheran and took hostage 66 Americans. Thus beginning the Iranian Hostage Crisis.

McCloy now persuaded Jimmy Carter to freeze all Iran's assets in the United States. This was the day before Iran's $4.05 million interest payment was due on its $500 million loan. As this was not now paid, Chase Manhattan Bank announced that the Iranian government was in default. The bank was now allowed to seize all of Iran's Chase accounts and used this money to "offset" any outstanding Iranian loans. In fact, by the end of this process, the bank ended up in profit from the deal.

John Jay McCloy died in Stamford, Connecticut, on 11th March, 1989.

Primary Sources

(1) Drew Pearson & Jack Anderson, The Case Against Congress (1968)

Fletcher Knebel in the Des Moines Register carefully listed the numerous gifts presented to the Eisenhower farm, including a John Deere tractor with a radio in it, a completely equipped electric kitchen, landscaping improvements and ponies and Black Angus steers-worth, all together, more than half a million dollars. Compare this outpouring to the $1,200 deep freeze-and the resulting uproar over it - given to President Truman by a Milwaukee friend of General Harry Vaughn. But no newspaper dug into the highly compromising fact that the upkeep of the Eisenhower farm was paid for by three oilmen - W. Alton Jones, chairman of the executive committee of Cities Service; B. B. (Billy) Byars of Tyler, Texas, and George E. Allen, director of some 20 corporations and a heavy investor in oil with Major Louey Kung, nephew of Chiang Kai-shek. They signed a strictly private lease agreement, under which they were supposed to pay the farm costs and collect the profits. Internal Revenue, after checking into the deal, could find no evidence that the oilmen had attempted to operate the farm as a profitable venture. Internal Revenue concluded that the money the oilmen poured into the farm could not be deducted as a business expense but had to be reported as an outright gift. Thus, by official ruling of the Internal Revenue Service, three oilmen gave Ike more than $500,000 at the same time he was making decisions favorable to the oil industry. The money went for such capital improvements as: construction of a show barn, $30,000; three smaller barns, about $22,000; remodeling of a schoolhouse as a home for John Eisenhower, $10,000; remodeling of the main house, $110,000; landscaping of 10 acres around the Eisenhower home, $6,000; plus substantial outlays for the staff including a $10,000-ayear farm manager.

How the money was paid is revealed in a letter dated January 28, 1958, and written from Gettysburg by General Arthur S. Nevins, Ike's farm manager. Addressed to George E. Allen in Washington and B. B. Byars in Tyler, Texas, it began, "Dear George and Billy" and discussed the operation of the farm in some detail. It said, in part:

"New subject - The funds for the farm operation are getting low. So would each of you also let me have your check in the usual amount of $2,500. A similar amount will be transferred to the partnership account from W. Alton Jones's funds."

In the left-hand corner of the letter is the notation that a carbon copy was being sent to W. Alton Jones.

During his eight years in the White House, Dwight Eisenhower did more for the nation's private oil and gas interests than any other President. He encouraged and signed legislation overruling a Supreme Court decision giving offshore oil to the Federal Government. He gave office space inside the White House to a committee of oil and gas men who wrote a report recommending legislation that would have removed natural-gas pipelines from control by the Federal Power Commission. In his appointments to the FPC, every commissioner Ike named except one, William Connole, was a pro-industry man. When Connole objected to gas price increases, Eisenhower eased him out of the commission at the expiration of his term.

On January 19, 1961, one day before he left the White House, Eisenhower signed a procedural instruction on the importation of residual oil that required all importers to move over and sacrifice 15 percent of their quotas to newcomers who wanted a share of the action. One of the major beneficiaries of this last-minute executive order happened to be Cities Service, which had had no residual quota till that time but which under Ike's new order was allotted about 3,000 barrels a day. The chief executive of Cities Service was W. Alton Jones, one of the three faithful contributors to the upkeep of the Eisenhower farm.

Three months later, Jones was flying to Palm Springs to visit the retired President of the United States when his plane crashed and Jones was killed. In his briefcase was found $61,000 in cash and travelers' checks. No explanation was ever offered - in fact none was ever asked for by the complacent American press - as to why the head of one of the leading oil companies of America was flying to see the ex-President of the United States with $61,000 in his briefcase.

(2) Jonathan Kwitny, Endless Enemies (1984)

In 1961 John Foster Dulles was dead. Allen Dulles had been reappointed to head the CIA as the very first decision announced by President-elect Kennedy. And President Eisenhower retired to a 576-acre farm near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The farm, smaller then, had been bought by General and Mrs. Eisenhower in 1950 for $24,000, but by 1960 it was worth about $1 million. Most of the difference represented the gifts of Texas oil executives connected to Rockefeller oil interests. The oilmen acquired surrounding land for Eisenhower under dummy names, filled it with livestock and big, modern barns, paid for extensive renovations to the Eisenhower house, and even wrote out checks to pay the hired help.

These oil executives were associates of Sid Richardson and Clint Murchison, billionaire Texas oilmen who were working with Rockefeller interests on some Texas and Louisiana properties and on efforts to hold up the price

of oil. From 1955 to 1963, the Richardson, Murchison, and Rockefeller interests (including Standard Oil Company of Indiana, which was 11-36 percent Rockefeller-held at the time of the Senate figures referred to earlier, and International Basic Economy Corporation, which was 100 percent Rockefeller-owned and of which Nelson Rockefeller was president) managed to give away a $900,000 slice of their Texas-Louisiana oil property to Robert B. Anderson, Eisenhower's secretary of the treasury.

In the Eisenhower cabinet, Anderson led the team that devised a system under which quotas were mandated by law on how much oil each company could bring into the U.S. from cheap foreign sources. This bonanza for entrenched power was enacted in 1958 and lasted fourteen years. Officially, it was done because of the "national interest" in preventing a reliance on foreign oil.

In effect, the import limits held U.S. oil prices artificially high, depleted domestic reserves, and reduced demand for oil overseas, thereby lowering foreign oil prices so that European and Japanese manufacturers could compete better with their U.S. rivals. It is difficult, of course, for a layman to understand how any of these things is in the national interest.

Meanwhile, President Kennedy turned the State Department over to Dean Rusk, who had held various high positions in the department under President Truman. For nine years - the entire Eisenhower interregnum for the Democrats and then some - Rusk had been occupied as president of the Rockefeller Foundation.

Has anybody stopped to think that from 1953 until 1977, the man in charge of U.S. foreign policy had been on the Rockefeller family payroll? And that from 1961 until 1977, he (meaning Rusk and Kissinger) was beholden to the Rockefellers for his very solvency?

(3) John J. McCloy, The Warren Report: Part 4, CBS Television (28th June, 1967)

There have been a number of suggestions that the Commission, for example, was only motivated by a desire to put - to make things quiet, so as to give comfort to the Administration, or give comfort to the people of the country, that there was nothing vicious about this. Well, that wasn't the attitude that we had at all.

I know what my attitude, when I first went down, I was convinced that there was something phony between the Ruby and the Oswald affair, that forty-eight hours after the assassination, here's this man shot in the police station. I was pretty skeptical about that. But as time went on and we heard witnesses and weighed the witnesses - but just think how silly this charge is.

Here we were seven men, I think five of us were Republicans. We weren't beholden to any Administration. Besides that, we - we had our own integrity to think of. A lot of people have said that you can rely upon the distinguished character of the Commission. You don't need to rely on the distinguished character of the Commission. Maybe it was distinguished, and maybe it wasn't. But you can rely on common sense. And you know that seven men aren't going to get together, of that character, and concoct a conspiracy, with all of the members of the staff we had, with all of the investigative agencies - it would have been a conspiracy of a character so mammoth and so vast that it transcends any - even some of the distorted charges of conspiracy on the part of Oswald.

I think that if there's one thing I would do over again, I would insist on those photographs and the X-rays having been produced before us. In the one respect, and only one respect there, I think we were perhaps a little oversensitive to what we understand was the sensitivities of the Kennedy family against the production of colored photographs of the body, and so forth.

But those exist. They're there. We had the best evidence in regard to that the pathology in respect to the President's wounds. It was our own choice that we didn't subpoena these photographs, which were then in the hands of the Kennedy family. I say, I wish - I don't think we'd have subpoenaed them. We could have gotten - Mr. Justice Warren was talking to the Kennedy family about that at that time. I thought that he was really going to see them, but it turned out that he hadn't.

(4) William G. Hyland, John J. McCloy, 1895-1989, Foreign Affairs (Spring 1989)

Few men are privileged to say that they were "present at the creation," to borrow Dean Acheson's felicitous phrase. John J. McCloy could make that claim with great pride, for he was assistant secretary of war during World War II, and he was one of a small circle of FDR's trusted advisers who were aware of the Manhattan Project. Thus, at a critical moment, John McCloy was in a position to change world history.

It was June 18, 1945, at the White House. President Truman was canvassing the views of his senior advisers on the prospect of invading Japan; various views were offered and just before the meeting broke up Harry Truman said, "We haven't heard from you, McCloy, and no one leaves this meeting without standing up and being counted." John McCloy proceeded to stand up and be counted: we ought to have our heads examined if we do not seek a political end to the war before an invasion, he said. We have two instruments to use: first, we could assure the Japanese that they could retain their emperor. Second, he said, we could warn them of the existence of the atomic bomb-a subject that was virtually taboo even in this restricted company. Truman was impressed, and sympathetic to the point about the emperor. He assigned McCloy and Secretary of War Henry Stimson to work out a plan, but history turned in a different direction-toward Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The point is not whether Mr. McCloy was right, but that he stands as an example of the bold and candid counsel provided by that heroic generation of men and women who served their country in peace and war, and served so wisely after Pearl Harbor. Indeed, Mr. McCloy served in various capacities and he was quick to remind us that he began as an artillery officer in World War I. Among his many accomplishments was his service as High Commissioner for Germany after World War II, when he and Konrad Adenauer carefully nurtured the young Federal Republic back into the European family. Later, in 1961, he began another career, this time advising successive presidents as the chairman of the presidential advisory committee on arms control and disarmament-known in Washington simply as the McCloy Committee.

(5) Glen Yeadon, The Nazi Hydra in America (2001)

In 1949, John McCloy was appointed High Commissioner of Germany. McCloy was not the first choice. Lewis Douglas, the head of the Finance Division of the Control Council was. However, Douglas agreed to step aside in favor of McCloy. It appears nothing was being left to chance in post war Germany. The governing of post war Germany would be a family affair. The three most powerful men in post war Germany: High Commissioner McCloy, Douglas, Head of the Finance Division of the Control Council and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer were all brother-in laws. All three men had married daughters of the wealthy Fredrick Zinsser, a partner of JP Morgan. The Morgan empire would control the fate of Germany.

What little justice achieved under the Control Council and General Clay would now be rapidly undone. Up until 1940 McCloy had been a member of the law firm Cravath, de Gersdorff, Swaine and Wood. This law firm represented I.G. Farben and its affiliates. In 1940, McCloy was appointed Assistant Secretary of War. At least three other individuals from the same law firm turned up in the War Department. Alfred McCormick and Howard Peterson both served as assistants to the Secretary. Richard Wilmer was commissioned as a colonel after the war started and served in a similar vein. Peterson later served as the finance chairman of the National Committee Eisenhower for President, 1951-1953.

The career of McCloy is one sympathetic to fascism and warrants a closer look. Henry Stimson appointed McCloy as assistant secretary of war. Roosevelt had selected Stimson to head up the War Department in 1940 in an attempt to make the war effort a bipartisan effort and to blunt any criticism of the upcoming war by the Republicans. One of the first acts of Stimson upon taking over the War Department was to appoint McCloy as Special consultant to the War Department on German sabotage. Before 1940 ended McCloy was appointed as assistant secretary. As Secretary of State under Hoover, Stimson would surely have been aware of the cartels of I.G Farben and how the Hoover administration aided their formation. McCloy spent most of the 1930s in Paris working on a sabotage case stemming from WWI. In 1936, he shared a box with Hitler at the Olympics.

In one of his first acts as assistant secretary of war, McCloy helped plan the interment of Japanese Americans. Once the war began, McCloy followed the American troops across North Africa. Such travel by an assistant cabinet secretary was highly unusual. However, McCloy’s actions at the time partially revealed his motivation. While in North Africa, McCloy help forge an alliance with the Vichy France and Admiral Darlan.

McCloy continued to follow the advancing allied troops across Europe and into Germany. In the closing days of the war in Europe McCloy made one of his most noted decisions. After sixteen planes bombed, Rothenburg on March 31 McCloy ordered a stop to any further bombing of the city. According to McCloy, his reason was to preserve the historical medieval walled city. Additionally, McCloy ordered Major-General Jacob L. Devers that he could not use artillery in taking Rothenburg. The city would have to be liberated by infantry alone regardless of the cost in lives of GIs.

However, there are a few facts that McCloy and others since have conveniently left out. For instance, just two days before the bombing a German general with his division of troops left battered Nurnburg for Rothenburg. Together with the Nazi forces already stationed there, the general gave the order to defend the city to the last man. Also located in Rothenburg was Fa Mansfeld AG, a munitions maker that employed slave labor from Buchenwald.

By late 1943, the slaughter of Jews was reaching a feverish pace. The allies were then in a position to bomb the concentration camps to stop the slaughter. John McCloy was almost solely responsible for blocking the bombing of the death camps. Allied planes were already bombing the industrial plants associated with Auschwitz. However, McCoy in written memos advanced a bankers' argument that the cost would be prohibitive. Such missions would risk men and planes with little reduction in the Nazis war effort. McCloy even banned the bombing of the rail lines leading to the death camps.

While still in Europe as Assistant Secretary of War, McCloy helped block the executions of several Nazi war criminals. He returned to the United States and on November 8, 1945 delivered a speech before the Academy of Political Science in New York. McCloy blasted the infamous JCS 1067 directive and the Morganethau Plan in an effort to prevent the decartelization of I.G. Farben and decartelization in general. He belittled the operating capacity of Germany’s industrial plant. Note: the allied bombing of Germany destroyed - at most - twenty percent of Germany’s industrial production.

As Congress was being bombarded with a lobbying effort to go easy on Germany, the agents of the Nazis were proceeding according to the plan. Unfortunately, too many members of Congress were sympathetic to the Nazis. With out exception they were all either conservative Dixiecrats or Republicans. Nebraska’s Senator Kenneth Wherry, Mississippi’s Democrat James Eastland and Indiana’s Republican Homer Capehart were just some of the many Congressmen that stood up and denounced the decartelization of Germany. Capehart was perhaps one of the more vicious in his speech before the Senate he blamed Morganethau for the mass starvation of the German people rather than the Nazis. He continued by claiming that the technique of hate had earned both Morganethau and Bernard Berstien the title of America’s Himmler.

While General Clay had reduced the sentences of numerous war criminals it was when John McCloy arrived as the High Commissioner of Germany that the doors of Landsberg prison were thrown. Even before McCloy arrived in Germany, he had blocked some executions of war criminals. Both Clay and McCloy acted with their respective advisory committees.

General Clay was advised by the Simpson Committee. Sitting on the Simpson Committee were Judge Edward Leroy van Roden, of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and Justice Gordon Simpson, of the Texas Supreme Court. The committee was appointed after Lieutenant Colonel Willis N. Everett, Jr., the defense counsel for the seventy-four defendants charged in the Malmedy massacre petitioned the United States Supreme Court that that the defendants had not received a fair trial. The Supreme Court ruled that it did not have jurisdiction but Everett’s petition forced the Secretary of the War, Royall to appoint the commission. The only evidence that the Simpson Committee relied upon came from the defendants and German clergy working to free all war criminals. In post-war Germany the clergy was uniformly sympathetic to the Nazis. The dissenters had been sent to the concentration camps where many of them perished.

(6) Article on Earl J, Carroll, the lawyer who managed to get Alfried Krupp freed from prison, True Magazine (August, 1954)

The terms of Carroll's employment were simple. He was to get Krupp out of prison and get his property restored. The fee was to be 5 per cent of everything he could recover. Carroll got Krupp out and his fortune returned, receiving for his five-year job a fee of, roughly, $25 million.