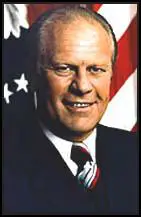

Gerald Ford

Leslie King was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on 14th July, 1913. His parents divorced when he was an infant and his mother remarried a paint salesman in Michigan. Leslie's name was changed to that of his stepfather, Gerald Rudolph Ford.

An outstanding sportsman he won a football scholarship to the University of Michigan, before studying law at Yale University. Ford graduated in 1941 and after being admitted to the bar began work in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

During the Second World War Ford served in the United States Navy and saw action in Okinawa, Wake Island, Taiwan, the Philippines and the Gilbert Islands. By the time he was discharged in 1946 had reached the rank as lieutenant commander.

A member of the Republican Party, Ford was elected to the House of Representatives in 1946. He was re-elected to the next eleven Congresses. He soon developed a reputation as a right-wing politician. As Harold Jackson pointed out: "He built up an impressive record of flat-earth conservatism. He voted against federal aid for education and housing, repeatedly resisted increases in the minimum wage, tried to block the introduction of medical care for the elderly, and consistently fought any measures to combat pollution. At the same time he supported virtually all increases in defence spending."

On the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963 his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." Gerald Ford was invited to join the commission under the chairmanship of Earl Warren. Other members of the commission included Richard B. Russell, Thomas Hale Boggs, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy and John S. Cooper.

One possible reason Johnson selected Ford was that he was under the control of J. Edgar Hoover. According to Bobby Baker (Wheeling and Dealing), who was himself under investigation for his corrupt relationship with politicians, businessmen and call-girls, Ford had been secretly taped by the FBI when he had attended meetings with Fred Black at the Sheraton-Carlton Hotel in Washington.

J. Lee Rankin became chief counsel for the Warren Commission. He then appointed Norman Redlich as his special assistant. Redlich began investigating the relationship between Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby. He was especially interested in why Oswald appeared to be heading towards Ruby's apartment after the assassination.

According to William C. Sullivan (The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover's FBI) Gerald Ford provided J. Edgar Hoover with information about the activities of staff members of the commission. "Hoover was delighted when Gerald Ford was named to the Warren Commission. The director wrote in one of his internal memos that the bureau could expect Ford to 'look after FBI interests,' and he did, keeping us fully advised of what was going on behind closed doors. He was our man, our informant, on the Warren Commission."

Hoover ordered that the FBI should carry out an investigation of Norman Redlich. He discovered that Redlich was on the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, an organization considered by Hoover to have been set-up to "defend the cases of Communist lawbreakers". Redlich had also been critical of the activities of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

This information was leaked to a group of right-wing politicians. On 5th May, 1964, Ralph F. Beermann, a Republican Party congressman, made a speech claiming that Redlich was associated with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Beermann called for Redlich to be removed as a staff member of the Warren Commission. He was supported by Karl E. Mundt who said: "We want a report from the Commission which Americans will accept as factual, which will put to rest all the ugly rumors now in circulation and which the world will believe. Who but the most gullible would believe any report if it were written in part by persons with Communist connections?"

Gerald Ford joined in the attack and at one closed-door session of the Warren Commission he called for Norman Redlich to be dismissed. However, Rankin and Earl Warren both supported him and he retained his job. However, after this, Redlich posed no threat to the theory that Oswald was the lone gunman.

The original first draft of the Warren Commission Report stated that a bullet had entered Kennedy's "back at a point slightly above the shoulder and to the right of the spine." Ford realized that this provided a serious problem for the single bullet theory. As Michael L. Kurtz has pointed out (The JFK Assassination Debates): "If a bullet fired from the sixth-floor window of the Depository building nearly sixty feet higher than the limousine entered the president's back, with the president sitting in an upright position, it could hardly have exited from his throat at a point just above the Adam's apple, then abruptly change course and drive downward into Governor Connally's back."

In 1997 the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) released a document that revealed that Ford had altered the first draft of the report to read: "A bullet had entered the base of the back of his neck slightly to the right of the spine." Ford had elevated the location of the wound from its true location in the back to the neck to support the single bullet theory.

The Republican Party surprisingly nominated the extreme conservative, Barry Goldwater, in the 1964 presidential election. During the election campaign Goldwater called for an escalation of the war against North Vietnam. In comparison to Goldwater, Lyndon B. Johnson was seen as the 'peace' candidate. People feared that Goldwater would send troops to fight in Vietnam. Johnson, on the other hand, argued that he was not willing: "to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves."

In the 1964 presidential election. Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been a popular leader during his year in office, easily defeated Barry Goldwater by 42,328,350 votes to 26,640,178. Johnson gained 61 per cent of the popular vote, giving him the largest majority ever achieved by an American president.

Another consequence of the election was that the House of Representatives had the largest Democratic majority since 1936. Gerald Ford was elected as minority leader by the slim margin of 73 to 67. During the Tet Offensive Ford called on Johnson to "Americanise the war". At that time, the US already had 500,000 troops fighting in the country. Johnson later described Ford as "so dumb he can't fart and chew gum at the same time."

By 1968, the popularity of the Democratic Party was in decline. Lyndon B. Johnson decided not to stand and was replaced by Hubert Humphrey as the party's presidential candidate. With progressive forces in the country unhappy with Humphrey's support of the Vietnam War, and with George Wallace collecting over 9 million votes in the South, it was no surprise when Richard Nixon won the election. Nixon received 31,770,237 votes against 31,270,533 for Humphrey.

Ford worked closely with Nixon's new administration. Alexander Butterfield later claimed that Nixon always had the minority leader totally under his thumb. He added: "He was a tool of the Nixon administration, like a puppy dog. They used him when they had to - wind him up and he'd go."

In 1970 two of Nixon's conservative nominees to the Supreme Court (Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell) failed their Senate confirmation hearings. Ford joined forces with Richard Nixon and Attorney General John N. Mitchell in an effort to get liberal justice, William O. Douglas, to resign. Stories were spread that Douglas was in the pay of the Parvin Foundation. In April 1970 Ford moved to impeach Douglas, the first major modern era attempt to impeach a member of the Supreme Court. Ford gained very little support for his actions and the hearings were brought to a close and no public vote on the matter was taken.

In 1973, Nixon's vice-president, Spiro Agnew was investigated for extortion, bribery and income-tax violations while governor of Maryland. On 10th October, 1973 resigned as vice-president. Nixon attempted to appoint John Connally as Agnew's replacement. However, Nixon was warned that his appointment would not be confirmed by Congress. Nixon therefore selected Ford instead.

Gerald Ford became president when Richard Nixon was also forced to resign over the Watergate Scandal in August, 1974. Ford therefore became the first man in history to become the president of the United States without having been elected as either president or vice president. Ford nominated Nelson Rockefeller as his vice president. During his confirmation hearings it was revealed that over the years he had made large gifts of money to government officials such as Henry Kissinger.

On 8th September, 1974, Ford controversially granted Richard Nixon a full pardon "for all offences against the United States" that might have been committed while in office. The pardon brought an end all criminal prosecutions that Nixon might have had to face concerning the Watergate Scandal.

On October 17, 1974, Ford vetoed the bill that would significantly strengthen the Freedom Of Information Act, calling it “unconstitutional and unworkable.” However, in November the House of Representatives and the Senate overrode President Ford’s veto.

In December, 1974, Seymour Hersh of the New York Times, published a series of articles claiming that the Central Intelligence Agency had been guilty of illegal activities. In his memoirs, Ford said that he feared a congressional investigation would result in "unnecessary disclosures" that could "cripple" the CIA. He and his aides quickly decided that he needed to prevent an independent congressional investigation. He therefore appointed Nelson Rockefeller to head his own investigation into these allegations.

Other members of the Rockefeller Commission included C. Douglas Dillon, Ronald Reagan, John T. Connor, Edgar F. Shannon, Lyman L. Lemmitzer, and Erwin N. Griswold. Executive Director of the task-force was David W. Belin, the former counsel to the Warren Commission and leading supporter of the magic bullet theory. In 1973 Berlin had published his book, November 22, 1963: You are the Jury, in which he defended the Warren Report as an historic, "unshakeable" document.

In her book, Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI, Kathryn S. Olmsted, wrote: "His choice for chairman, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, had served as a member of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which monitored the CIA. Members Erwin Griswold, Lane Kirkland, Douglas Dillon, and Ronald Reagan had all been privy to CIA secrets in the past or noted for their strong support of governmental secrecy."

The journalist, Joseph Kraft, argued that he feared that the Rockefeller report would not end "the terrible doubts which continue to eat away at the nation." This was reflected in public opinion polls taken at the time. Only 33% had confidence in the Rockefeller Commission and 43% believed that the commission would turn into "another cover-up".

At a meeting with some senior figures at the New York Times, including Arthur O. Sulzberger and A. M. Rosenthal, President Gerald Ford let slip the information that the CIA had been involved in conspiracies to assassinate political leaders. He immediately told them that this information was off the record. This story was leaked to the journalist Daniel Schorr who reported the story on CBS News. As Schorr argued in his autobiography, Staying Tuned: " President Ford moved swiftly to head off a searching congressional investigation by extending the term of the Rockefeller commission and adding the assassination issue to its agenda."

Rockefeller's report was published in 1975. It included information on some CIA abuses. As David Corn pointed out in Blond Ghost: "the President's panel revealed that the CIA had tested LSD on unsuspecting subjects, spied on American dissidents, physically abused a defector, burgled and bugged without court orders, intercepted mail illegally, and engaged in plainly unlawful conduct". The report also produced details about MKULTRA, a CIA mind control project.

Rockefeller also included an 18-page section on the assassination of John F. Kennedy (Allegations Concerning the Assassination of John F. Kennedy). A large part of the report was taken up with examining the cases of E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis. This was as a result of both men being involved in the Watergate Scandal. The report argued that a search of agency records showed that Sturgis had never been a CIA agent, informant or operative. The commission also accepted the word of both men that they were not in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

The Rockefeller Commission also looked at the possibility that John F. Kennedy had been fired at by more than one gunman. After a brief summary of the Warren Commission (1964) and the Ramsay Clark Panel (1968) investigations, Rockefeller concluded: "On the basis of the investigation conducted by its staff, the Commission believes that there is no evidence to support the claim that President Kennedy was struck by a bullet fired from either the grassy knoll or any other position to his front, right front or right side, and that the motions of the President's head and body, following the shot that struck him in the head, are fully consistent with that shot having come from a point to his rear, above him and slightly to his right."

Nelson Rockefeller also looked at the possible connections between E. Howard Hunt, Lee Harvey Oswald, Jack Ruby and the CIA. He claimed that there was no "credible evidence" that Oswald or Ruby were CIA agents or informants. Nor did Hunt ever have contact with Oswald. The report argues: "Hunt's employment record with the CIA indicated that he had no duties involving contacts with Cuban exile elements or organizations inside or outside the United States after the early months of 1961... Hunt and Sturgis categorically denied that they had ever met or known Oswald or Ruby. They further denied that they ever had any connections whatever with either Oswald or Ruby."

This section of the report reached the following conclusions: "Numerous allegations have been made that the CIA participated in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The Commission staff investigated these allegations. On the basis of the staff's investigation, the Commission concluded there was no credible evidence of any CIA involvement."

The report was condemned as a cover-up. Dr. Cyril H. Wecht accused the Rockefeller Commission of "deliberately distorting and suppressing" part of his testimony as to the nature of Kennedy's head and neck wounds. Wecht demanded that a full transcript of his testimony be released. Rockefeller refused on the grounds that the commission proceedings were confidential.

Dissatisfaction with the report resulted in other investigations into the CIA taking place. This included those led by Frank Church, Richard Schweiker, Louis Stokes, Lucien Nedzi and Otis Pike.

Ford's ability to govern was handicapped by the way he had obtained power and the fact that he had to deal with a Congress controlled by the Democratic Party. On over fifty occasions Congress vetoed his proposed legislation. Ford also struggled with rampant inflation and the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression.

At the Republican National Convention in August, 1976, Ford defeated Ronald Reagan and won the party's nomination. His presidential campaign did not go well. In one of his televised debates with Jimmy Carter he stated "there is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe". Ford, was also handicapped by his association with Richard Nixon and the Watergate Scandal, and was defeated by Carter by 40,276,040 to votes to 38,532,360.

After his defeat in 1976 Gerald Ford retired to his home in Palm Springs, California. In 1980, Ronald Reagan gave serious consideration to Ford as a potential vice-presidential running mate. Negotiations between the Reagan and Ford camps took place at the Republican National Convention in Detroit. According to an article by Richard V. Allen (New York Times Magazine, July 30, 2000). Ford conditioned his acceptance on Reagan's agreement to an unprecedented "co-presidency", giving Ford the power to control key executive branch appointments (such as Henry Kissinger as Secretary of State and Alan Greenspan as Treasury Secretary). After rejecting these terms, Reagan offered the vice-presidential nomination to George H. W. Bush.

In January 2006, Ford was treated for pneumonia. In August of that year it was reported that he had been fitted with a pacemaker. Gerald Ford died on 26th December, 2006.

Primary Sources

(1) William C. Sullivan, The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover's FBI (1979)

Hoover was delighted when Gerald Ford was named to the Warren Commission. The director wrote in one of his internal memos that the bureau could expect Ford to "look after FBI interests," and he did, keeping us fully advised of what was going on behind closed doors. He was our man, our informant, on the Warren Commission.

Ford's relationship with Hoover went back to Ford's first congressional campaign in Michigan. Our agents out in the field kept a watchful eye on local congressional races and advised Hoover whether the winners were friends or enemies. Hoover had a complete file developed on each incoming congressman. He knew their family backgrounds, where they had gone to school, whether or not they played football, and any other tidbits he could weave into a subsequent conversation.

Gerald Ford was a friend of Hoover's, and he first proved it when he made a speech not long after he came to Congress recommending a pay raise for J. Edgar Hoover, the great director of the FBI. He proved it again when he tried to impeach Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a Hoover enemy.

(2) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

Edward Bennett Williams said, "Bobby, you can never figure what a jury will do. It's a roll of the dice. Think about it. Bill Bittman's tough. Bobby Kennedy put him on the Jimmy Hoffa case because he's like a bulldog, and he put Hoffa in Jail. There's a lot of press hysteria connected with your case and the political implications are grave."

I thought about it while Williams silently drove the car and then said, "Ed, absolutely under no circumstances do you have authority to tell Bittman I'll plead guilty to one damn thing. If I do, the press will play it that I got my wrists slapped, that I copped out, that a fix was in. The assumption of total guilt will be with me the rest of my life."

"Well," he said, "it will be with you if a jury finds you guilty, too."

"Maybe they can kill me," I said, "but they can't eat me. I'll go to trial."

"I concur with your decision," Williams said. "I didn't want to influence you, because if something goes wrong then you're the guy who will have to pay the piper."

I knew that William O. Bittman was a tough nut. He had hard, cold eyes and by his own admission was humorless. A bulky former line-backer for Marquette University, lie wore his hair in a crewcut and reminded me of a man the nation Would later get to know - H. R. Halderman of the Nixon staff. I knew from his wiretapping, electronic buggings, and the pressure he'd applied to potential witnesses that Bittman would play hardball all the way (I learned that when the FBI bugged Fred Black's Sheraton-Carlton Suite for six months, one of the periodic visitors there was a congressman named Jerry Ford. He was friendly with Black, but I don't know what he used the suite for). Yet, I could not bear the thought of being labeled as a guy who'd stolen from his best friend. I wanted to get my relationship with Senator Kerr on the record and was willing to run risks in order to do that. Edward Bennett Williams had been preparing my case for almost two years; I had confidence in his ability to get my story across.

(3) Exchange between Max Frankel and President Gerald Ford during a televised debate on 6th October, 1976.

Max Frankel : I'm sorry, could I just follow - did I understand you to say, sir, that the Russians are not using Eastern Europe as their own sphere of influence in occupying most of the countries there and making sure with their troops that it's a Communist zone, whereas on our side of the line the Italians and the French are still flirting with the possibility of Communism?

Gerald Ford: I don't believe, Mr. Frankel that the Yugoslavians consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. I don't believe that the Rumanians consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. I don't believe that the Poles consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. Each of those countries is independent, autonomous; it has its own territorial integrity. And the United States does not concede that those countries are under the domination of the Soviet Union. As a matter of fact, I visited Poland, Yugoslavia and Rumania to make certain that the people of those countries understood that the President of the United States and the people of the United States are dedicated to their independence, their autonomy and their freedom.

(4) Mike Feinsilber, Gerald Ford and the Warren Report (2nd July, 1997)

Thirty-three years ago, Gerald R. Ford took pen in hand and changed - ever so slightly - the Warren Commission's key sentence on the place where a bullet entered John F. Kennedy's body when he was killed in Dallas.

The effect of Ford's change was to strengthen the commission's conclusion that a single bullet passed through Kennedy and severely wounded Texas Gov. John Connally - a crucial element in its finding that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole gunman.

A small change, said Ford on Wednesday when it came to light, one intended to clarify meaning, not alter history.

''My changes had nothing to do with a conspiracy theory,'' he said in a telephone interview from Beaver Creek, Colo. ''My changes were only an attempt to be more precise.''

But still, his editing was seized upon by members of the conspiracy community, which rejects the commission's conclusion that Oswald acted alone.

''This is the most significant lie in the whole Warren Commission report,'' said Robert D. Morningstar, a computer systems specialist in New York City who said he has studied the assassination since it occurred and written an Internet book about it.

The effect of Ford's editing, Morningstar said, was to suggest that a bullet struck Kennedy in the neck, ''raising the wound two or three inches. Without that alteration, they could never have hoodwinked the public as to the true number of assassins.''

If the bullet had hit Kennedy in the back, it could not have struck Connolly in the way the commission said it did, he said.

The Warren Commission concluded in 1964 that a single bullet - fired by a ''discontented'' Oswald - passed through Kennedy's body and wounded his fellow motorcade passenger, Connally, and that a second, fatal bullet, fired from the same place, tore through Kennedy's head.

The assassination of the president occurred Nov. 22, 1963, in Dallas; Oswald was arrested that day but was shot and killed two days later as he was being transferred from the city jail to the county jail.

Conspiracy theorists reject the idea that a single bullet could have hit both Kennedy and Connally and done such damage. Thus they argue that a second gunman must have been involved.

Ford's changes tend to support the single-bullet theory by making a specific point that the bullet entered Kennedy's body ''at the back of his neck'' rather than in his uppermost back, as the commission staff originally wrote.

Ford's handwritten notes were contained in 40,000 pages of records kept by J. Lee Rankin, chief counsel of the Warren Commission.

They were made public Wednesday by the Assassination Record Review Board, an agency created by Congress to amass all relevant evidence in the case. The documents will be available to the public in the National Archives.

The staff of the commission had written: ''A bullet had entered his back at a point slightly above the shoulder and to the right of the spine.''

Ford suggested changing that to read: ''A bullet had entered the back of his neck at a point slightly to the right of the spine.''

The final report said: ''A bullet had entered the base of the back of his neck slightly to the right of the spine.''

Ford, then House Republican leader and later elevated to the presidency with the 1974 resignation of Richard Nixon, is the sole surviving member of the seven-member commission chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren.

(5) Michael L. Kurtz, The JFK Assassination Debates (2006)

Virtually every serious Kennedy assassination researcher believes that the Warren Commission's single bullet theory is essential to its conclusion that only one man fired shots at President Kennedy and Governor Connally. The awkwardness of the Mannlicher-Carcano's bolt action mechanism, which forced FBI experts to fire two shots in a minimum of 2.25 seconds, even without aiming, coupled with the average time of 18.3 film frames per second as measured on Abraham Zapruder's camera, constitute a timing constraint that compels the conclusion either that Kennedy and Connally were struck by the same bullet, or that two separate gunmen fired two separate shots at the two men. Although a handful of researchers contend that the first shot struck Kennedy at frame Z162 or Z189, thereby allowing sufficient time for Oswald to fire a separate shot with the Carcano and strike Connally at frame Z237, the vast majority of assassination scholars maintain one of two scenarios. First, both Kennedy and Connally were struck by the same bullet at frame Z223 or Z224, evidenced by the quick flip of the lapel on Connally's suit jacket as the bullet passed through his chest. Second, the first bullet struck Kennedy somewhere between frames Z210 and Z224, and the second bullet struck Connally between frames Z236 and Z238, evidenced by the visual signs on the film of Connally reacting to being struck.

The evidence clearly establishes, however, that Kennedy and Connally were struck by separate bullets. The location of the bullet wound in Kennedy's back has given rise to considerable controversy. Originally, the Warren Commission staff draft of the relevant section of the Warren Report stated that "a bullet had entered his back at a point slightly above the shoulder and to the right of the spine." The problem lay in the course of the bullet through Kennedy's body. If a bullet fired from the sixth-floor window of the Depository building nearly sixty feet higher than the limousine entered the president's back, with the president sitting in an upright position, it could hardly have exited from his throat at a point just above the Adam's apple, then abruptly change course and drive downward into Governor Connally's back. Therefore, Warren Commissioner Gerald Ford deliberately changed the draft to read: "A bullet had entered the base of the back of his neck slightly to the right of the spine." Suppressed for more than three decades, Ford's deliberate distortion was released to the public only through the actions of the ARRB. When this alteration first surfaced in 1997, Ford explained that he made the change for the sake of "clarity." In reality, Ford had elevated the location of the wound from its true location in the back to the neck to ensure that the single bullet theory would remain inviolate. The actual evidence demonstrates the accuracy of the initial draft. Bullet holes in Kennedy's shirt and suit jacket, situated almost six inches below the top of the collar, place the wound squarely in the back. Because JFK sat upright at the time, and because photographs and films show that neither the shirt nor the suit jacket rode up over his collar, the location of the bullet holes in the garments prove that the shot struck him in the back. Kennedy's death certificate places the wound at the level of the third thoracic vertebra. Autopsy photographs of the back place the wound in the back two to three inches below the base of the neck.

(6) Angus Mackenzie, The CIA's War at Home (1997)

The CIA would spend the next two decades fighting the release of documents to citizens who requested them under the FOIA. For CIA officials, whose lives were dedicated to secrecy, the logic behind the checks and balances of the three-branch system of government may have been incomprehensible. The idea that federal judges not trained in espionage could inspect CIA files and even order their release was enough to curdle the blood of secret operatives like Richard Ober. CIA officers felt that neither Congress nor the courts could comprehend the perils that faced secret agents. Their instinctive reaction, therefore, was to find any avenue by which they could avoid judicial or journalistic scrutiny.

A month after Congress enacted the new FOIA amendments, someone at the CIA leaked the news of MHCHAOS to Seymour Hersh at the New York limes. Hersh's article appeared on the front page of the December 22, r974, issue under the headline "Huge C.I.A. Operation Reported in U.S. against Antiwar Forces, Other Dissidents in Nixon Years." Although sparse in detail, the article revealed that the CIA had spied on U.S. citizens in a massive domestic operation, keeping 10,000 dossiers on individuals and groups and violating the 1947 National Security Act. Hersh reported that intelligence officials were claiming the domestic operations began as legitimate spying to investigate overseas connections to dissenters.

Gerald Ford, who only four and a half months earlier had assumed the presidency in the wake of Nixon's resignation, took the public position that the CIA would be ordered to cease and desist. William Colby, who had replaced James Schlesinger as CIA director, was told to issue a report on MHCHAOS to Henry Kissinger.

Apparently Ford was not informed that Kissinger was well aware of the operation. A few days later, after Helms categorically denied that the CIA had conducted "illegal" spying, Ford named Vice President Nelson Rockefeller to head a commission that would be charged with making a more comprehensive report. Ford's choice of Rockefeller to head the probe was most fortunate for Ober. Rockefeller was closely allied with Kissinger, who had been a central figure in the former New York governor's 1968 presidential primary campaign. Although Rockefeller was well regarded in media and political circles for his streak of independence, it was all but certain from the beginning that his report would amount to a cover-up.

In fact, Colby ran into trouble because he was willing to be more forthcoming about MHCHAOS than Rockefeller and Kissinger desired. After Colby's second or third appearance before the commission investigators, Rockefeller drew Colby aside and said, "Bill, do you really have to present all this material to us? We realize there are secrets that you fellows need to keep, and so nobody here is going to take it amiss if you feel there are some questions you can't answer quite as fully as you seem to feel you have to."

Because of MHCHAOS and Watergate, Congress began to investigate the CIA. On September 16, 1975, Senators Frank Church and John Tower called Colby to testify at a hearing about CIA assassinations. Colby showed up carrying a CIA poison-dart gun, and Church waved the gun before the television cameras. It looked like an automatic pistol with a telescopic sight mounted on the barrel. Producers of the evening newscasts recognized this as sensational footage, and just as surely Colby recognized that his days as director were numbered. He had not guarded the CIA secrets well enough.

Colby was fired on November 2, 1975. His successor was George Herbert Walker Bush, who had been serving as chief of the U.S. Liaison Office in Beijing. Bush's job would be delicate, perhaps impossible, and probably thankless; but as the former chairman of the Republican Party, he had already been in a similar position, guiding the party through the worst days of the Watergate scandal. He had supported Nixon as long as it was politically feasible, then finally had joined those who insisted on Nixon's departure.

(7) Daniel Schorr, Staying Tuned: A Life in Journalism (2001)

The disclosure that the CIA, in its domestic surveillance program code-named Operation Chaos, tapped wires and conducted break-ins caused a public stir that intervention in far-off Chile had not. Over the Christmas holiday in Vail, Colorado, President Ford, it would later emerge, had finally gotten to read the CIA inspector general's report, informally dubbed the Family Jewels.

It detailed a stunning list of 693 items of CIA malfeasance ranging from behavior-altering drug experiments on unsuspecting subjects, one of whom plunged to his death from a hotel window; to assassination plots against leftist third world leaders.

Anxious to keep congressional committees, already gearing up for investigations, from laying bare the worst of these, President Ford, on January 5, 1975, announced the appointment of a "blue-ribbon" commission to inquire into improper domestic operations. The panel was headed by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller and included such stalwarts as Gov. Ronald Reagan of California, retired general Lyman Lemnitzer, and former treasury secretary Douglas Dillon.

A few days later President Ford held a long-scheduled luncheon for New York Times publisher Arthur O. Sulzberger and several of his editors. Toward the end the subject of the newly named Rockefeller commission came up. Executive Editor A. M. Rosenthal observed that, dominated by establishment figures, the panel might not have much credibility with critics of the CIA. Ford nodded and explained that he had to he cautious in his choices because, with complete access to files, the commission might learn of matters, under presidents dating back to Truman, far more serious than the domestic surveillance they had been instructed to look into.

The ensuing hush was broken by Rosenthal. "Like what?"

"Like assassinations," the president shot back.

Prompted by an alarmed news secretary Ron Nessen, the president asked that his remark about assassinations be kept off the record.

The Times group returned to their bureau for a spirited argument about whether they could pass up a story potentially so explosive. Managing Editor E. C. Daniel called the White House in the hope of getting Nessen to ease the restriction from "off-the-record" to "deep background." Nessen was more adamant than ever that the national interest dictated that the president's unfortunate slip be forgotten. Finally, Sulzberger cut short the debate, saying that, as the publisher, he would decide, and he had decided against the use of the incendiary information.

This left several of the editors feeling quite frustrated, with the inevitable result that word of the episode began to get around, eventually reaching me. Under no off-the-record restriction myself, I enlisted CBS colleagues in figuring out how to pursue the story. Since Ford had used the word assassinations, we assumed we were looking for persons who had been murdered - possibly persons who had died under suspicious circumstances. We developed a hypothesis, but no facts.

On February 27, 1975, my long-standing request for another meeting with Director Colby came through. Over coffee we discussed Watergate and Operation Chaos, the domestic surveillance operation.

As casually as I could, I then asked, "Are you people involved in assassinations?"

"Not any more," Colby said. He explained that all planning for assassinations had been banned since the 1973 inspector general's report on the subject.

I asked, without expecting an answer, who had been the targets before 1973.

"I can't talk about it," Colby replied.

"Hammarskjold?" I ventured. (The UN. secretary-general killed in an airplane crash in Africa.)

"Of course not."

"Lumumba?" (The left-wing leader in the Belgian Congo who had been killed in 1961, supposedly by his Katanga rivals.)

"I can't go down a list with you. Sorry."

I returned to my office, my head swimming with names of dead foreign leaders who may have offended the American government. It was frustrating to be this close to one of the major stories of my career and not be able to get my hands on it. After a few days I decided I knew enough to go on the air even without the identity of corpses.

Because of President Ford's imprecision, I didn't realize that he was not referring to actual assassinations, but assassination conspiracies. All I knew was that assassination had been a weapon in the CIA arsenal until banned in a post-Watergate cleanup and that the president feared that investigation might expose the dark secret. l sat down at my typewriter and wrote, "President Ford has reportedly warned associates that if current investigations go too far they could uncover several assassinations of foreign officials involving the CIA..."

The two-minute "tell" story ran on the Evening News on February 28. While I had been mistaken in suggesting actual murders, my report opened up one of the darkest secrets in the CIA's history.

President Ford moved swiftly to head off a searching congressional investigation by extending the term of the Rockefeller commission and adding the assassination issue to its agenda. The commission hastily scheduled a new series of secret hearings in the vice president's suite in the White House annex. Richard Helms, who had already testified once, was called home again from his ambassador's post in Tehran for two days of questioning by the commission's staff and four hours before the commission on April 28.

I waited with colleagues and staked-out cameras outside the hearing room, the practice being to ask witnesses to make remarks on leaving. As Helms emerged, I extended my hand in greeting, with a jocular "Welcome back'." I was forgetting that I was the proximate reason for his being back.

His face ashen from fatigue and strain, he turned livid.

"You son of a bitch," he raged. "You killer, you cocksucker Killer Schorr - that's what they ought to call you!"

He then strode before the cameras and gave a toned-down version of his tirade. "I must say, Mr. Schorr, I didn't like what you had to say in some of your broadcasts on this subject. As far as I know, the CIA was never responsible for assassinating any foreign leader."

"Were there discussions of possible assassinations?" I asked.

Helms began losing his temper again. "I don't know when I stopped beating my wife, or you stopped beating your wife. Talk about discussions in government? There are always discussions about practically everything under the sun!"

I pursued Helms down the corridor and explained to him the presidential indiscretion that had led me to report "assassinations."

Calmer now, he apologized for his outburst and we shook hands. But because other reporters had been present, the story of his tirade was in the papers the next day.

(8) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI (1996)

Beyond his ideological reasons for opposing a CIA investigation, Ford was also influenced by partisan and institutional considerations. Hersh's initial stories had accused Richard Nixon's CIA of domestic spying - not Lyndon Johnson's CIA or John Kennedy's CIA. If, indeed, the improprieties took place on the Republicans' watch, then too much attention to these charges could hasten the GOP's post-Watergate slide and boost the careers of crusading Democrats. Ford also opposed wide-ranging investigations because he felt responsible for protecting the presidency. "I was absolutely dedicated to doing whatever I could to restore the rightful prerogatives of the presidency under the constitutional system," he recalls. His aides list Ford's renewal of presidential power after Watergate as one of the greatest achievements of his administration. This lifelong conservative believed that he had a duty to control the congressional investigators and restore the honor of his new office.

Within days of Hersh's first story, Ford's aides recommended that he set up an executive branch investigative commission to avoid "finding ourselves whipsawed by prolonged Congressional hearings." In a draft memo to the president written on 27 December, Deputy Chief of Staff Richard Cheney explained that the president had several reasons to establish such a commission: to avoid being put on the defensive, to minimize "damage" to the CIA, to head off "Congressional efforts to further encroach on the executive branch," to demonstrate presidential leadership, and to reestablish Americans' faith in their government.

Ford's aides cautioned that this commission, formally called the Commission on CIA Activities within the United States, must not appear to be "a 'kept' body designed to whitewash the problem." But Ford apparently did not follow this advice. His choice for chairman, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, had served as a member of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which monitored the CIA. Members Erwin Griswold, Lane Kirkland, Douglas Dillon, and Ronald Reagan had all been privy to CIA secrets in the past or noted for their strong support of governmental secrecy.

In a revealing move, the president also appointed General Lyman Lemnitzer, the same chairman of the Joint Chiefs whose office in 1962 had been charged by Congressman Jerry Ford with a "totalitarian" attempt to suppress information. In short, Ford's commissioners did not seem likely to conduct an aggressive investigation. Of the "true-blue ribbon" panel's eight members, only John Connor, a commerce secretary under Lyndon Johnson, and Edgar Shannon, a former president of the University of Virginia, brought open minds to the inquiry, according to critics.

Many congressmen, including GOP senators Howard Baker and Lowell Weicker, found the commission inadequate. Some supporters of the CIA, such as columnist Joseph Kraft, worried that many Americans would view the commission as part of a White House cover-up. Although Kraft personally admired the commissioners, he feared that their findings would not be credible and therefore would not reduce "the terrible doubts which continue to eat away at the nation." A public opinion poll confirmed these reservations. Forty-nine percent of the people surveyed by Louis Harris believed that an executive commission would be too influenced by the White House, compared with 35 percent who supported Ford's action. A clear plurality - 43 percent - believed that the commission would turn into "another cover-up," while 33 percent had confidence in the commission and 24 percent were unsure. The New York Times editorial board, also suspicious of the panel, urged congressmen not to allow the commission to "become a pretext to delay or circumscribe their own independent investigation." A week later, the Times again reminded Congress of its duty to conduct a "long, detailed" examination of the intelligence community: "Three decades is too long for any public institution to function without a fundamental reappraisal

of its role."

(9) The Rockefeller Commission (1975)

On the basis of the investigation conducted by its staff, the Commission believes that there is no evidence to support the claim that President Kennedy was struck by a bullet fired from either the grassy knoll or any other position to his front, right front or right side, and that the motions of the President's head and body, following the shot that struck him in the head, are fully consistent with that shot having come from a point to his rear, above him and slightly to his right...

Hunt's employment record with the CIA indicated that he had no duties involving contacts with Cuban exile elements or organizations inside or outside the United States after the early months of 1961... Hunt and Sturgis categorically denied that they had ever met or known Oswald or Ruby. They further denied that they ever had any connections whatever with either Oswald or Ruby...

Numerous allegations have been made that the CIA participated in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The Commission staff investigated these allegations. On the basis of the staff's investigation, the Commission concluded there was no credible evidence of any CIA involvement.

(10) Richard V. Allen, How the Bush Dynasty Almost Wasn’t, New York Times Magazine (30th July, 2000)

What I remember most about entering Ronald Reagan’s suite early on the third evening of the 1980 Republican convention, the night of his nomination, was the silence. It’s not that there weren’t plenty of people around. William J. Casey, Reagan’s campaign manager; Richard Wirthlin, his pollster; and his advisers Peter Hannaford, Michael Deaver, and Edwin Meese were all there in the candidate’s elegantly appointed rooms on the sixty-ninth floor of the Detroit Plaza Hotel. So, too, was Reagan, dressed in a casual shirt and tan slacks. The entire group was seated on a large U-shaped couch, hushed, as if they were watching some spellbinding movie on TV.

The silence in the room was in marked contrast to the steadily rising noise at the Joe Louis Arena. There, word was spreading that Reagan was going to choose Gerald Ford, the former president and his bitter adversary in the 1976 primaries, to be his running mate.

As Reagan’s foreign policy adviser, I didn’t have much business getting involved in the selection of a vice president. But as someone who signed on with Reagan because I admired his principled criticism of the foreign policy of the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations, I couldn’t help venturing to the suite to see what was going on. And so, at 5:30 in the evening, before I was to head over to the convention, I walked up the single flight of stairs that separated Reagan’s floor from mine. It didn’t take long for my suspicions to be confirmed. As I stepped into the hallway, there, coming out of Reagan’s rooms and flanked by his Secret Service detail, was a tanned and fit Gerald Ford.

Once the former president and I had exchanged pleasantries, I made my way past security to Reagan’s suite. Alone among those gathered on the couch, the nominee looked up and greeted me. I asked if he needed anything before I left for the arena. “Oh, no,” he replied, “but thanks.”

As I turned to leave, he asked, “What do you think of the Ford deal?”

“What deal?” I responded, genuinely surprised that the two parties were already working out details. In addition to the vice-presidential slot, Reagan said, “Ford wants Kissinger as secretary of state and Greenspan at treasury.” My instant response was, “That is the craziest deal I have ever heard of.” And it was.

This election year, both major presidential candidates conducted highly structured searches for their running mates. Though it was only 20 years ago, the process in 1980 could not have been more different from the one today. It is hard to imagine an unexpected vice-presidential pick at the last minute, like John Kennedy’s selection of Lyndon Johnson in 1960, Richard Nixon’s choice of Spiro Agnew in 1968, or even George Bush Sr.’s elevation of Dan Quayle in 1988 - all of which caught the candidates’ advisers by surprise.

But it was Ronald Reagan’s nomination of Governor Bush’s father that bears special telling. Reagan’s selection of Bush in Detroit represented a turnabout within six hours; it came only when the negotiations with Ford, having taken on a life of their own, appeared to have reached an impasse. Had the talks succeeded and had Ford been selected, the Reagan campaign, crippled by infighting, might well have lost to the Carter-Mondale ticket in the fall. Had Reagan and Ford managed to win the election, it’s very likely that their administration would have been hobbled by an unworkable power-sharing arrangement. It’s also possible that the Republicans might have a different candidate today.

There are many plausible versions of how and why Reagan chose George Bush as his running mate, but most are wide of the mark. One conventional view is that Reagan, about to be nominated, recognized that he "needed a moderate" like Bush to balance the ticket; another version has it that Reagan, supposedly unschooled in foreign affairs, saw the wisdom of naming someone with extensive experience in the field to offset his own shortcomings. Yet another explanation holds that Reagan, a Californian, needed “geographic balance” and got that in Bush, with his Connecticut and Texas lineage.

These explanations are wrong. George Bush was picked at the very last moment and largely by a combination of chance and some behind-the-scenes maneuvering. Many Reagan advisers have claimed a deal was never close. The postconvention media commentary has largely reflected this view. In fact, Meese and Deaver have gone so far as to declare that Bush was their first choice all along. I take exception to their account. I saw a very different story unfold and saw it from a privileged vantage point. From the moment I walked into that suite until the moment Bush was finally selected, I was the only person to remain in Reagan’s presence throughout the adventure. With detailed notes to back up my memory, this is what I saw at the dawn of the Reagan revolution on that long night in Detroit.

(11) Harold Jackson, The Guardian (28th December, 2006)

There has been endless speculation whether this pardon was part of a deal to persuade Nixon to abandon his rearguard fight against impeachment. Certainly there were well-attested, if tangential, discussions on the subject between Vice-President Ford and the White House chief of staff, Alexander Haig. But the consensus is that, even as his tenure crumbled, Nixon remained confident that his longstanding influence over Ford would stop him facing trial.

Ford had, in fact, not been Nixon's first choice as vice-president when Spiro Agnew was forced out of office in 1973 for corruption. The president wanted one of his closest political allies, former governor of Texas John Connolly, to take over, but he was warned of insuperable opposition in Congress where, under the unusual terms of the recently adopted 25th amendment, any nominee required confirmation by a majority in both houses.

So, after a review of a wide variety of candidates ranging from Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York on the Republican left to Senator Barry Goldwater on the party's right, Nixon settled for the minority leader in the House of Representatives.

He did so to ensure an easy confirmation - which he got. But, according to the former White House chief of staff HR Haldeman, Nixon also calculated that a House familiar with Ford's inadequacies would never risk presidential impeachment, since that would put Ford into the Oval Office. Henry Kissinger acknowledged in his memoirs that he made a similar judgment at the time.

Nixon and Ford had been politically associated since both were young congressmen in 1948. Alexander Butterfield - Haldeman's White House deputy who revealed to a startled Senate committee Nixon's habit of taping his conversations reminisced in 1983 that the president had always had the minority leader totally under his thumb. "He was a tool of the Nixon administration, like a puppy dog. They used him when they had to - wind him up and he'd go 'arf 'arf."

(12) Jon Wiener, The Nation (27th December, 2006)

Gerald Ford is gone, but he lives on in two of his key appointees: Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. Their impact on America today is greater than Ford's, who died Tuesday at 93.

Ford appointed Rumsfeld his chief of staff when he took office after Nixon's resignation in 1974. The next year, when he made the 42-year-old Rumsfeld the youngest secretary of defense in the nation's history, he named 34-year-old Dick Cheney his chief of staff, also the youngest ever.

Those two Ford appointees worked together ever since. The Bush White House assertion of unchecked presidential power stems from the lessons they drew from their experience of working for the weakest president in recent American history. "For Dick and Don," Harold Meyerson wrote in The American Prospect last July, "the frustrations of the Ford years have been compensated for by the abuses of the Bush years."

Ford also named a new head of the CIA - a former Texas congressman named George H. W. Bush. Thus you could also credit also Ford with launching the Bush dynasty.

It was during Ford's presidency that the last Americans left Vietnam - that photo of them struggling to get into that chopper on the roof of the Saigon embassy remains our most powerful image of American defeat, and it shadows our current debate about how to get out of Iraq.

Ford did leave one positive legacy, as Meyerson reminds us: his supreme court appointee, John Paul Stevens. Few remember it today, but when the Court majority appointed Bush president in December, 2000, Stevens wrote a blistering dissent, damning the other Republican appointees for their blatant partisanship. And this year Stevens wrote the majority opinion in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld declaring that the military tribunals at Guantanamo violated the Geneva Convention.

But we wouldn't need Stevens if we didn't have Rumsfeld, Cheney and Bush - that's the legacy of Gerald Ford.

(13) Gerald Ford, The Warren Commission (2007)

It is true that you can't ignore coincidences, but there are many reasons those coincidences occur. Conspiracies may or may not have existed or occurred somewhere, such as the government-sanctioned plot to kill Castro, but considering the meticulousness of our investigation, we were confident that we would have uncovered links from those to Oswald and to Kennedy's assassination had there been any. I have become increasingly adamant that we were correct as more and more experts have questioned and then verified our conclusions...

The echoes of the assassin's shots had hardly died out before everyone began speculating 'whodunit.' The trouble was, given the kind of turbulence going on in the world at the time (not to mention covertly in the U.S.), there were plenty of groups with plausible motives to assassinate President Kennedy, which helped to encourage speculation. Notwithstanding that, our Commission's findings were that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin and that he worked alone -- there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The same went for Jack Ruby....

I have been accused of changing some wording on the Warren Commission Report to favor the lone-assassin conclusion. That is absurd. Here is what the draft said: 'A bullet had entered his back at a point slightly above the shoulder and to the right of the spine.' To any reasonable person, 'above the shoulder and to the right' sounds very high and way off the side -- and that's what it sounded like to me. That would have given the totally wrong impression. Technically, from a medical perspective, the bullet entered just to the right at the base of the neck, so my recommendation to the other members was to change it to say, 'A bullet had entered the back of his neck, slightly to the right of the spine.' After further investigation, we then unanimously agreed that it should read, 'A bullet had entered the base of his neck slightly to the right of the spine.'

The reason some things appeared to be suspicious was possibly because there were people who apparently did have things to hide. It came out later there was a government-sanctioned plot to kill Fidel Castro. There seemed to also have been a scramble to cover that up which did interfere marginally with our investigation, as I testified to the HSCA (House Select Committee on Assassinations). It was really more of a problem for the CIA. JFK's assassination and our investigation into it put certain classified and potentially embarrassing operations in danger of being exposed. Their reaction was to hide or destroy some information, which can easily be misinterpreted as collusion in JFK's assassination.

(14) Joe Stephens, Washington Post (8th August, 2008)

Confidential FBI files released this week to The Washington Post detail the inner workings of a secret back channel that Gerald R. Ford opened in 1963 between J. Edgar Hoover's FBI and the Warren Commission's independent investigation into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

The existence of the private conduit has long been known, first disclosed in documents released 30 years ago. Now, newly obtained, previously classified records detail one visit Ford made to one of Hoover's deputies in December 1963 -- three weeks after being named to the commission.

Declassified FBI memos on Ford's interactions with the bureau are among scores of documents in the FBI's previously confidential file on the former president, who died in December 2006. At the request of The Post, the FBI this week released 500 pages of the bureau's voluminous file.

A December 1963 memo recounts that Ford, then a Republican congressman from Michigan, told FBI Assistant Director Cartha D. "Deke" DeLoach that two members of the seven-person commission remained unconvinced that Kennedy had been shot from the sixth-floor window of the Texas Book Depository. In addition, three commission members "failed to understand" the trajectory of the slugs, Ford said.

Ford told DeLoach that commission discussions would continue and reassured him that those minority points of view on the commission "of course would represent no problem," one internal FBI memo shows. The memo does not name the members involved and does not elaborate on what Ford meant by "no problem."

Ford also told DeLoach that Chief Justice Earl Warren, who headed the commission, had told its members that "they should strive to have their hearings completed and the findings made public prior to July, 1964, when the Presidential campaigns will begin to get hot. He stated it would be unfair to present the findings after July." They missed their deadline, concluding in a report issued Sept. 24, 1964, that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination. Much of the material in the FBI file concerns intelligence about Ford's political adversaries when he was president, especially organizations that the bureau thought might disrupt Ford's appearances around the country. But the file also sheds light on the investigation into Kennedy's assassination and the FBI's relationship with Ford, and it shows how the bureau strove to curry favor with powerful politicians.

Another memo in the file, previously released with Warren Commission materials in 1978, details how Ford approached DeLoach in 1963 and offered to secretly inform the bureau about the inner workings of the then-ongoing Warren Commission investigation.

"Ford indicated he would keep me thoroughly advised as to the activities of the Commission," DeLoach wrote. "He stated this would have to be done on a confidential basis, however he thought it should be done."