The Invasion of the Philippines in 1941

The Philippines (consisting of 7,641 islands) had become a colonial territory to the United States in 1898. It was granted independent commonwealth status since 1934, but remained of great strategic importance to US Pacific defence policy. The natural resources of the Philippines include nickel (world’s second-largest producer), copper, timber, nickel, petroleum, silver, gold, cobalt, and salt. The Japanese government was especially jealous of American control of this country. (1)

In October, 1935, Field Marshal Douglas MacArthur was appointed as head of the Philippines Commonwealth Army. His army had less than 4,000 regular troops and 20,000 poorly trained irregulars. MacArthur complained that his equipment and weapons were "more or less obsolete" being mainly American cast offs. On 31st December 1937, MacArthur officially retired from the Army. He ceased to represent the U.S. as military adviser to the government, but remained as adviser to President Manuel L. Quezon, in a civilian capacity. (2)

On 23rd July, 1941, Japanese troops moved into the southern part of Indochina. This put them in a position to threaten Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines. Three days later Roosevelt recalled MacArthur, aged 61, to active duty in the U.S. Army as a major general, and named him commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). MacArthur was promoted to lieutenant general the following day, and then to general on 20 December. (3)

Roosevelt's advisers told him that newspaper, public and official opinion was uniformly opposed to any appeasement of Japan. In September, 1941, Roosevelt was told that 67 per cent of the public was ready to risk war with Japan to keep her from becoming more powerful. However, he felt that the country was not quite ready for war and so his main strategy was to string out the negotiations. Roosevelt told the British Ambassador, Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, that "very little was going on as regards these talks" but added he was "gaining useful time". (4)

General MacArthur was also provided with $10 million from the President's Emergency Fund in order to mobilize the Philippine Army. He was also promised a large force of over 100 B-17 Flying Fortresses, the long-range heavy bomber. Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War, believed that these bombers gave America the ability to "completely damage" Japanese supply lines to the Southwest Pacific, endowing the United States with "a vital power of defense there". The British Ambassador cabled Churchill: "The President had a good deal to say about the great effect that their planting some heavy bombers at the Philippines was expected to have upon the Japs." (5)

By October, 1941, MacArthur felt sufficiently confident of progress to send a triumphant memorandum to Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, describing his 227 assorted fighters, bombers and reconnaissance aircraft (including 35 B-17s) as a "tremendously strong offensive and defensive force" and the Philippines as "the key or base point of the US defence line". In the same month a similarly complacent assessment of US strength in the Philippines was provided by the Joint Chiefs to Roosevelt. (6)

MacArthur commanded roughly 135,000 troops in the US Army Forces Far East. Most were deployed for the defence of the two main islands, Luzon and Mindanao. On 8th December, 1941, Japanese air strikes from Formosa destroyed half of MacArthur's air force (including two squadrons of B-17s) on the ground. The air strikes were followed up on 10th December by air attacks on Manila by the 11th Air Fleet that destroyed Philippine torpedo reserves. At the same time the Japanese Army landed virtually unopposed, to capture air bases at three points in northern Luzon. What was left of the Far East Air Force was all but destroyed over the next few days. (7) Japanese troops seized the American garrisons at Shanghai and Tianjin. Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong. Guam, Wake Island and Midway Island. (8)

The main 14th Army landing at Lingayen Gulf, north of the capital, Manila, on 22nd December, completely overran the inexperienced Filipino troops deployed around the Luzon coastline. The relatively small Japanese force of 57,000 men made quick advances. Within two days of the Japanese landing, MacArthur had reverted to pre-July 1941 plan of attempting to hold only Bataan while waiting for a relief force to come. Most of the American and some of the Filipino troops were able to retreat back to Bataan, but without most of their supplies, which were abandoned in the confusion. (9)

In February 1942, as Japanese forces tightened their grip on the Philippines, President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to relocate to Australia. On the night of 12 March 1942, MacArthur and a select group that included his wife Jean, son Arthur, left the Philippines. His famous speech, in which he said, "I came through and I shall return", was first made on Terowie railway station in South Australia, on 20th March. Washington asked MacArthur to amend his promise to "We shall return". He ignored the request. (10)

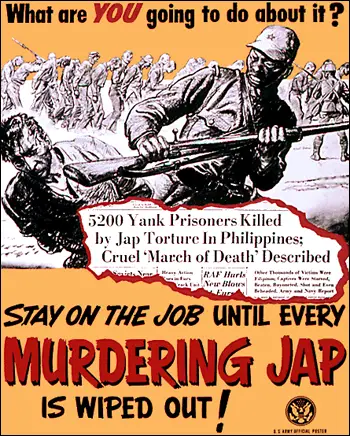

The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of U.S. forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on Corregidor in May. An estimated 76,000 prisoners of war (of whom 12,000 were American), captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake what became known as the Bataan Death March, to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the north. "Many of those who died were clubbed or bayoneted to death when, too weak to walk further, they stumbled and fell. Others were ordered out of the ranks, beaten, tortured and killed." (11)

The march resulted in the death of around 650 American soldiers. "Over the days which followed, few of their guards allowed them to rest in the shade or lie down. More than 7,000 American and Filipino soldiers from Bataan died. Some 400 Filipino officers and NCOs of the 91st Division were killed with swords in a massacre on 12 April at Batanga. Of the 63,000 who made it alive to the camp, hundreds more died each day. Also 2,000 of the survivors of Corregidor died from hunger or disease in their first two months of captivity." (12)

Primary Sources

(1) James F. Byrnes, Speaking Frankly (1947)

A large Congressional party, headed by Vice President Garner, had gone to Manila to witness the inauguration of Manuel Quezon as the first President of the Philippine Commonwealth. There, Americans in all walks of life had expressed to us their concern over the increasing indications of Japan's aggressive intentions. Therefore, when we stopped in Japan I made a special effort to inquire into Japanese naval appropriations and naval construction. A study of the Japanese budget for 1936 readily revealed that at least half of the total was devoted to the army and navy. Members of our Embassy staff were convinced that the published budget disclosed only part of the naval appropriations. The published figures were alarming enough in themselves and when we returned to this country I urged the President to seek means for acquiring still more accurate estimates of Japan's naval strength.

(2) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

Hitler rapidly decided to follow the Japanese example by declaring war on the United States himself. When Ribbentrop pointed out that the Tripartite Pact only bound Germany to assist Japan in the event of an attack on her by some other Power, and that to declare war on the USA would be to add to the number of Germany's opponents, Hitler dismissed these as unimportant considerations. He seems never to have weighed the possible advantages of deferring an open breach with America as long as possible and allowing the USA to become involved in a war in the Pacific which would reduce the support she was able to give to give to Great Britain.

(3) Adolf Hitler, speech (11th December, 1941)

I understand only too well that a world-wide distance separates Roosevelt's ideas and mine. Roosevelt comes from a rich family and belongs to the class whose path is smoothed in the democracies. I was only the child of a small, poor family and had to fight my way to work and industry. When the Great War came, Roosevelt occupied a position where he got to know only its pleasant consequences, enjoyed by those who do business while others bleed. I was only one of those who carried out orders as an ordinary soldier and actually returned from the war just as poor as I was in the autumn of 1914. I shared the fate of millions, and Franklin Roosevelt only the fate of the so-called upper ten thousand.

(4) George Ball, quoted in William Stevenson's book, A Man Called Intrepid (1976)

If Hitler had not made this decision (to declare war on the United States) and if he had simply done nothing, there would have been an enormous sentiment in the United States... that the Pacific was now our war and the European war was for the Europeans, and we Americans should concentrate all our efforts on Japan.

(5) Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948)

When Churchill and his staff came to Washington in December of 1941, they were prepared for the possibility of an announcement by Roosevelt that due to the rage of the American people against Japan and the imperilled position of American forces in the Philippines and other islands, the war in the Pacific must be given precedence.

(11) Antony Beevor, The Second World War (2014)

The appalling complacency of colonial society had produced a self-deception largely based on arrogance. A fatal underestimation of their attackers included the idea that all Japanese soldiers were very short-sighted and inherently inferior to western troops. In fact they were immeasurably tougher and had been brainwashed into believing that there was no greater glory than to give their lives for their Emperor. Their commanders, imbued with a sense of racial superiority and convinced of Japan's right to rule over East Asia, remained impervious to the fundamental contradiction that their war was supposed to free the region from western tyranny.

(2) Winston Churchill, The Second World War (1950)

In the Philippines, where General MacArthur commanded, a warning indicating a grave turn in diplomatic relations had been received on November 20. Admiral Hart, commanding the modest United States Asiatic Fleet, had already been in consultation with the adjacent British and Dutch naval authorities, and,

in accordance with his war plan, had begun to disperse his forces to the southward, where he intended to assemble a striking force in Dutch waters in conjunction with his prospective allies.

He had at his disposal only one heavy and two light cruisers, besides a dozen old destroyers and various auxiliary vessels. His strength lay almost entirely in his submarines, of which he had twenty-eight. At 3 a.m. on December 8 Admiral Hart intercepted a message giving the staggering news of the attack on Pearl

Harbour. He at once warned all concerned that hostilities had begun, without waiting for confirmation from Washington. At dawn the Japanese dive-bombers struck, and throughout the ensuing days the air attacks continued on an ever-increasing scale.

On the 10th the naval base at Cavite was completely destroyed by fire, and on the same day the Japanese made their first landing in the north of Luzon. Disasters mounted swiftly. Most of the American air forces were destroyed in battle or on the ground, and by December 20 the remnants had been withdrawn to Port Darwin, in Australia. Admiral Hart's ships had begun their southward dispersal some days before, and only the submarines remained to dispute the sea with the enemy. On December 21

the main Japanese invasion force landed in Lingayen Gulf, threatening Manila itself, and thereafter the march of events was not unlike that which was already in progress in Malaya; but the defence was more prolonged.

(3) General Douglas MacArthur wrote about the invasion of the Philippines in December 1941 in his autobiography, Reminiscences of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (1964).

At 3.40 on Sunday morning, December 8, 1941, Manila time, a long-distance telephone call from Washington told me of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but no details were given. It was our strongest military position in the Pacific. Its garrison was a mighty one, with America's best aircraft on strongly defended fields, adequate warning systems, anti-aircraft batteries, backed up by our Pacific Fleet. My first impression was that the Japanese might well have suffered a serious setback.

We had only one radar station operative and had to rely for air warning largely on eye and ear. At 9:30 a.m. our reconnaissance planes reported a force of enemy bombers over Lingayen Gulf heading toward Manila. Major General Lewis H. Brereton, who had complete tactical control of the Far East Air Force, immediately ordered pursuit planes up to intercept them. But the enemy bombers veered off without contact.

When this report reached me, I was still under the impression that the Japanese had suffered a setback at Pearl Harbor, and their failure to close in on me supported that belief. I therefore contemplated an air reconnaissance to the north, using bombers with fighter protection, to ascertain a true estimate of the situation and to exploit any possible weaknesses that might develop on the enemy's front. But subsequent events quickly and decisively changed my mind. I learned, to my astonishment, that the Japanese had succeeded in their Hawaiian attack, and at 11:45 a report came in of an over- powering enemy formation closing in on Clark Field. Our fighters went up to meet them, but our bombers were slow in taking off and our losses were heavy. Our force was simply too small to smash the odds against them.

(4) William Leahy, I Was There (1950)

MacArthur was convinced that an occupation of the Philippines was essential before any major attack in force should be made on Japanese-held territory north of Luzon. The retaking of the Philippines seemed to be a matter of great interest to him. He said that he had sufficient ground and air forces for the operation and that his only additional needs were landing-craft and naval support.

Nimitz developed the Navy's plan of by-passing the Philippines and attacking Formosa. He did not see that Luzon, including Manila Bay, had advantages that were not possessed by other areas in the Philippines that could be taken for a base at less cost in lives and material. As the discussions progressed, however, the Navy Commander in the Pacific admitted that developments might indicate a necessity for occupation of the Manila area. Nimitz said that he had sufficient forces to carry out either operation. It was highly pleasing and unusual to find two commanders who were not demanding reinforcements.

Roosevelt was at his best as he tactfully steered the discussion from one point to another and narrowed down the area of disagreement between MacArthur and Nimitz. The discussion remained on a friendly basis the entire time, and in the end only a relatively minor difference remained - that of an operation to retake the Philippine capital, Manila. This was solved later, when the idea of beginning our Philippine invasion at Leyte was suggested, studied and adopted.

(5) The Manchester Guardian (20th October, 1944)

American landings on Suluan, a small but important island in a commanding. position on the eastern fringe of the Central Philippines, were reported yesterday by the Japanese. This news, which so far is unconfirmed by Allied sources, follows heavy "softening" raids on Formosa, the supply base between the Philippines and the Japanese mainland.

It may indicate the first step towards the fulfillment, of General MacArthur's promise that he would return, eventually to these islands, which were overrun by the Japanese in 1942. The Japanese report, which was contained in a message from Manila, said that "enemy forces started landing operations on Tuesday morning."

Another Japanese broadcast, also unconfirmed, said that an Allied '"fleet sailed the same day into the Gulf of Leyte and bombed and shelled the coast. It added that the Allied forces were being opposed.

The Japanese News Agency last night reported that American forces have "attempted a landing " on the island of Leyte. The agency said that a new large task force, comprising the Fifth United States Fleet under. Admiral Spruance and another fleet '"under the command o General MacArthur," on Tuesday penetrated, into the Leyte Gulf between Luzon and Mindanao islands.

(6) The Manchester Guardian (21st October, 1944)

General MacArthur's invasion forces have established three firm beachheads on the east coast of the island of Leyte, in the Central Philippines, and last night were reported to be pushing inland against stiffening Japanese resistance. According to a broadcast from the Leyte area, picked up in San Francisco. Tacloban airfield, on the north-eastern tip of Leyte Island, has been captured.

Earlier President Roosevelt announced in Washington that the operations are going according to plan, with extremely light losses.

The Japanese were taken by surprise because, as General MacArthur explained in his announcement of the landing, they were expecting attacks on the large island of Mindanao, south of Leyte. "The strategic results of the capturing of the Philippines will be decisive." MacArthur said. " To the south 500,000 men will be cut off without hope of support and the culmination will be their destruction at the leisure of the Allies."

Thus General MacArthur has fulfilled the promise to return that the made two and a half years ago when his forces left the Philippines. An American broadcaster said that the Commander-in-Chief waded ashore with one of the landing parties and quoted him as saying, "I will stay for the duration now."

The President of the Philippine Commonwealth, Sergio Osmena, with members of his Cabinet, went with the American forces and already has established the seat of government on Philippine soil.

(7) General Douglas MacArthur wrote a report for Harry S. Truman where he advocated that Tomoyuki Yamashita should be tried as a war criminal.

It is not easy for me to pass penal judgment upon a defeated adversary in a major military campaign. I have reviewed the proceedings in vain search for some mitigating circumstances on his behalf. I can find none. Rarely has so cruel and wanton a record been spread to public gaze. Revolting as this may be in itself, it pales before the sinister and far reaching implication thereby attached to the profession of arms. The soldier, be he friend or foe, is charged with the protection of the weak and unarmed. It is the very essence and reason for his being.

When he violates this sacred trust, he not only profanes his entire cult but threatens the very fabric of international society. The traditions of fighting men are long and honorable. They are based upon the noblest of human traits-sacrifice. This officer, of proven field merit, entrusted with high command involving authority adequate to responsibility, has failed this irrevocable standard; has failed his duty to his troops, to his country, to his enemy, to mankind; has failed utterly his soldier faith. The transgressions resulting therefrom as revealed by the trial are a blot upon the military profession, a stain upon civilization and constitute a memory of shame and dishonor that can never be forgotten. Peculiarly callous and purposeless was the sack of the ancient city of Manila, with its Christian population and its countless historic shrines and monuments of culture and civilization, which with campaign conditions reversed had previously been spared.

It is appropriate here to recall that the accused was fully forewarned as to the personal consequences of such atrocities. On October 24 - four days following the landing of our forces on Leyte - it was publicly proclaimed that I would "hold the Japanese Military authorities in the Philippines immediately liable for any harm which may result from failure to accord prisoners of war, civilian internees or civilian non combatants the proper treatment and the protection to which they of right are entitled."