Daniel Schorr

Daniel Schorr was born in New York City on 31st August, 1916. His parents were Jewish immigrants, Tillie and Gedaliah Tchornemoretz, from what is now Belarus. After attending the College of the City of New York he contributed articles to the Jewish Daily Bulletin and the New York Journal American.

Schorr served in the United States Intelligence during the Second World War (1943-45). In 1946 he joined the Christian Science Monitor. Later he moved to the The New York Times. Schorr worked as a foreign correspondent and reported on the Marshall Plan, and the creation of the NATO alliance.

In 1953, Schorr was recruited by Ed Murrow to work for CBS News as its diplomatic correspondent in Washington. This included an investigation into the claims being made by Senator Joseph McCarthy. In 1955 he opened a CBS bureau in Moscow. Two years later Schorr carried out the first ever television interview with Nikita Khrushchev. Later that year Schorr was arrested by the police and deported from the Soviet Union.

Schorr returned to Washington and traveled with President Dwight Eisenhower to South America, Asia, and Europe. In 1959 he interviewed Fidel Castro in Havana. In 1960, Schorr was assigned to Bonn as CBS bureau chief for Germany and Eastern Europe. He covered the Berlin crisis and the building of the Berlin Wall and reported events from all the Warsaw Pact countries. In 1964 Schorr was nearly sacked after reporting that Barry Goldwater was linked with a group of German right-wing military men.

Schorr returned to the United States in 1966 and reported on domestic issues. This included the presidencies of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon and the civil rights movement. According to Godfrey Hodgson: "In 1966... Schorr went to Washington. There he annoyed Nixon, Johnson's successor from 1969, by his critical reporting. Schorr was an unapologetic liberal. In 1970, he made a celebrated documentary for CBS Reports about healthcare called Don't Get Sick in America, published as a book in the same year."

In 1972 Schorr began working full-time on the Watergate Scandal. Schorr's reports on the Senate Watergate hearings earned him three Emmys. In June 1973, Bill Paley made attempts to censor Schorr's criticism of Richard Nixon. It was later discovered that Schorr had been added to Nixon's "enemies list" and as a result was investigated by the FBI.

As a result of the Watergate Scandal, on 9th August, 1974, Richard M. Nixon became the first president of the United States to resign from office. The new president, Gerald Ford, nominated Nelson Rockefeller as his vice president. During his confirmation hearings it was revealed that over the years he had made large gifts of money to government officials such as Henry Kissinger.

Later that year, Seymour Hersh of the New York Times, published a series of articles claiming that the Central Intelligence Agency had been guilty of illegal activities. In his memoirs, Ford said that he feared a congressional investigation would result in "unnecessary disclosures" that could "cripple" the CIA. He and his aides quickly decided that he needed to prevent an independent congressional investigation. He therefore appointed Rockefeller to head his own investigation into these allegations.

Other members of the Rockefeller Commission included C. Douglas Dillon, Ronald Reagan, John T. Connor, Edgar F. Shannon, Lyman L. Lemmitzer, and Erwin N. Griswold. Executive Director of the task-force was David W. Belin, the former counsel to the Warren Commission and leading supporter of the magic bullet theory. In 1973 Berlin had published his book, November 22, 1963: You are the Jury, in which he defended the Warren Report as an historic, "unshakeable" document.

In her book, Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI, Kathryn S. Olmsted, wrote: "His choice for chairman, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, had served as a member of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which monitored the CIA. Members Erwin Griswold, Lane Kirkland, Douglas Dillon, and Ronald Reagan had all been privy to CIA secrets in the past or noted for their strong support of governmental secrecy."

The journalist, Joseph Kraft, argued that he feared that the Rockefeller report would not end "the terrible doubts which continue to eat away at the nation." This was reflected in public opinion polls taken at the time. Only 33% had confidence in the Rockefeller Commission and 43% believed that the commission would turn into "another cover-up".

At a meeting with some senior figures at the New York Times, including Arthur O. Sulzberger and A. M. Rosenthal, President Gerald Ford let slip the information that the CIA had been involved in conspiracies to assassinate political leaders. He immediately told them that this information was off the record. This story was leaked to Daniel Schorr who reported the story on CBS News. As Schorr argued in his autobiography, Staying Tuned: A Life in Journalism: " President Ford moved swiftly to head off a searching congressional investigation by extending the term of the Rockefeller commission and adding the assassination issue to its agenda."

Rockefeller's report was published in 1975. It included information on some CIA abuses. As David Corn pointed out in Blond Ghost: Ted Shackley and the CIA Crusades: "the President's panel revealed that the CIA had tested LSD on unsuspecting subjects, spied on American dissidents, physically abused a defector, burgled and bugged without court orders, intercepted mail illegally, and engaged in plainly unlawful conduct". The report also produced details about MKULTRA, a CIA mind control project.

In July, 1975, Fletcher Prouty told Daniel Schorr that Alexander P. Butterfield had been the CIA's spy in the White House. Butterfield denied this claim and threatened to sue the two men for libel. Time Magazine reported: "Despite his impressive record, Schorr gets into trouble because he is often too eager and cuts corners. He has been known to behave like an anxious rookie out to impress by elbowing others aside and pushing hard. Just before the Watergate cover-up indictments, for example, he went on-camera to predict that the grand jury would name more than 40 people. Seven names came down. At CBS, Washington Correspondent Leslie Stahl cordially detests him because, she tells friends, he hogged her Watergate stories."

In February of 1976, the House of Representatives, voted to suppress the final report of its intelligence investigating committee. Schorr, who had been given an advance copy, leaked the information to Village Voice. This led to his suspension by CBS and an investigation by the House Ethics Committee in which Schorr was threatened with jail for contempt of Congress if he did not disclose his source. Schorr refused and eventually the committee decided 6 to 5 against a contempt citation.

Schorr left CBS and wrote an account of this Watergate story called Clearing the Air. In 1977 he was Regents Professor of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley and for three years wrote for the Des Moines Register-Tribune Syndicate.

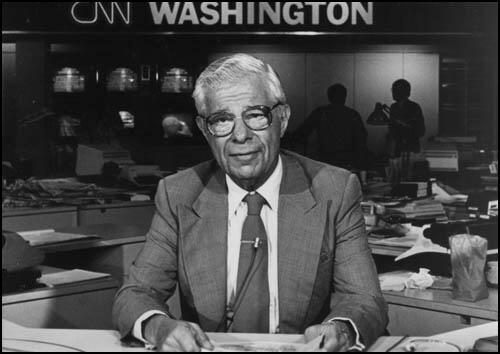

In 1979, Schorr was asked by Ted Turner to help create the Cable News Network. Schorr wrote his own contract, which specified that he should not be asked to do anything that contradicted his sense of ethical journalism. He serving in Washington as its senior correspondent until 1985, when he left in a dispute over an effort to limit his editorial independence.

Schorr found work at National Public Radio, contributing regularly to All Things Considered, Weekend Edition Saturday, and Weekend Edition Sunday. He told USA Today: "I have breathed the breath of freedom. Nobody ever told me here what not to do."

In 1996, Schorr received the Columbia University Golden Baton for "Exceptional Contributions to Radio and Television Reporting and Commentary." An award that is considered the equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize. Schorr has also been inducted into the Hall of Fame of the Society of Professional Journalists and in 2002, Schorr was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Schorr published his autobiography, Staying Tuned: A Life in Journalism, in 2001. He also wrote a regular column for the Christian Science Monitor. His final two books were The Idea of a Free Press (2006) and Come to Think of It: Notes on the End of the Millennium (2007).

Daniel Schorr died on 23rd July, 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Time Magazine (28th July, 1975)

The day after a story broke in the press alleging that the CIA had planted a spy in the White House, Colonel Fletcher Prouty telephoned CBS Newsman Daniel Schorr with the startling news that former Nixon Aide Alexander Butterfield was the man. Schorr rushed the retired Air Force officer onto the network's Morning News for his disclosure, which generated sensational headlines. But last week, when Butterfield denied Prouty's charges and hinted he might sue him for libel, the colonel, in an interview with his hometown paper in Springfield, Mass., expressed second thoughts. Then Prouty confused matters further with a switch back to his original story. This jack-in-the-box behavior roused questions not only about Prouty's reliability but Schorr's as well.

By week's end, grizzled Veteran Schorr, 58, thought his exposé was looking "awful." But he insists he had reason to trust Prouty because the colonel had earlier given him a rock-hard exclusive on his role in a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro. Still, Schorr concedes that he never took the time to check the Butterfield allegation with the two Air Force officers who Prouty claims gave him the information, or try very hard to reach Butterfield himself. Nevertheless, Schorr says, "I still think my only alternative was to go. We're in a strange business here in TV news. You can't check on the validity of everything... I can't be in a position of suppressing Prouty. What if he's right? I can't play God."

The controversy is not the first to embroil Schorr in recent years. Early in the Nixon Administration he angered the President by reporting, accurately, that there was no evidence to support Nixon's claim that he had programs ready to aid parochial schools. His reward: Nixon ordered the FBI to investigate him. During Watergate, Schorr became TV's most visible investigative reporter and shared three Emmys with his colleagues. Last February Schorr moved into new territory by reporting President Ford's fear that the clamor to investigate the CIA might reveal the agency's role in foreign assassination plots. Two months later, former CIA Director Richard Helms denounced Schorr's reporting as "lies" and called him "Killer Schorr, Killer Schorr." Recent disclosures by the Senate Intelligence Operations Committee have largely vindicated Schorr.

Despite his impressive record, Schorr gets into trouble because he is often too eager and cuts corners. He has been known to behave like an anxious rookie out to impress by elbowing others aside and pushing hard. Just before the Watergate cover-up indictments, for example, he went on-camera to predict that the grand jury would name more than 40 people. Seven names came down. At CBS, Washington Correspondent Leslie Stahl cordially detests him because, she tells friends, he hogged her Watergate stories.

(2) David Halberstam, The Powers That Be (1979)

Paley was in San Francisco for the (1964) Republican convention and he was in a foul mood. Because of his Eisenhower connections, he - had been committed to Bill Scranton, the good, establishment, respectable candidate that season, and this had made the Goldwater people particularly suspicious of CBS. That suspicion had not dimmed when Dan Schorr, then in Europe, had done a story connecting Goldwater with certain right-wing German military men, a story that brought to the fore all the incipient mistrust of the conservative politician. The fact that the Scranton people were exploiting this particular story at the convention made Paley doubly nervous. CBS was for a time barred from Goldwater's headquarters. Paley himself panicked as the pressure mounted, and demanded that Friendly fire Schorr. Friendly, who had just taken over as head of CBS News and who was in a frenzy, kept turning to his staff and asking what he should do. The staff considered this unseemly. The obvious answer was to pay no attention to Goldwater or Paley, particularly since Schorr's story seemed valid Friendly settled it by calling Schorr and repeatedly asking, "How could you do this to me? How could you do this to me?" as if Schorr had filed the story primarily as a way of putting Fred W. Friendly in the pressure cooker. "You've given me a clubfoot," Friendly told Schorr. The air was foul even as the convention was just starting, and Paley became convinced, as Schorr remained unfired, that he had too little control over his own News Department: Finally the Goldwater-German crisis was all resolved, there was a humiliating apology dictated to CBS by the Goldwater people and read over the air by Cronkite, and Schorr's job was saved, although his ego was bruised.

(3) H. R. Haldeman, The Ends of Power (1978)

Years later, former C.B.S. correspondent Dan Schorr called me. He was seeking information concerning the F.B.I. investigation Nixon had mounted against him in August, 1971.

Schorr later sent me his fascinating book Clearing the Air. In it I was interested to find that evidence he had gleaned while investigating the C.I.A. finally cleared up for me the mystery of the Bay of Pigs connection in those dealings between Nixon and Helms. "It's intriguing when I put Schorr's facts together with mine. It seems that in all of those Nixon references to the Bay of Pigs, he was actually referring to the Kennedy assassination."

(Interestingly, an investigation of the Kennedy assassination was a project I suggested when I first entered the White House. I had always been intrigued with the conflicting theories of the assassination. Now I felt we would be in a position to get all the facts. But Nixon turned me down.

According to Schorr, as an outgrowth of the Bay of Pigs, the CIA made several attempts on Fidel Castro's life. The Deputy Director of Plans at the CIA at the time was a man named Richard Helms.

Unfortunately, Castro knew of the assassination attempts all the time. On September 7, 1963, a few months before John Kennedy was assassinated, Castro made a speech in which he was quoted, 'Let Kennedy and his brother Robert take care of themselves, since they, too, can be the victims of an attempt which will cause their death.'

After Kennedy was killed, the CIA launched a fantastic cover-up. Many of the facts about Oswald unavoidably pointed to a Cuban connection.

1. Oswald had been arrested in New Orleans in August, 1963, while distributing pro-Castro pamphlets.

2. On a New Orleans radio programme he extolled Cuba and defended Castro.

3. Less than two months before the assassination Oswald visited the Cuban consulate in Mexico City and tried to obtain a visa.

In a chilling parallel to their cover-up at Watergate, the CIA literally erased any connection between. Kennedy's assassination and the CIA. No mention of the Castro assassination attempt was made to the Warren Commission by CIA representatives. In fact, Counter-intelligence Chief James Angleton of the CIA called Bill Sullivan of the FBI and rehearsed the questions and answers they would give to the Warren Commission investigators, such as these samples:

Q. Was Oswald an agent of the C.I.A.

A. No.

Q. Does the CIA have any evidence showing that a conspiracy existed to assassinate Kennedy?

A. No.

And here's what I find most interesting: Bill Sullivan, the FBI man that the CIA called at the time, was Nixon's highest-ranking loyal friend at the FBI (in the Watergate crisis, he would risk J. Edgar Hoover's anger by taking the 1969 FBI wiretap transcripts ordered by Nixon and delivering them to, Robert Mardian, a Mitchell crony, for safekeeping).

It's possible that Nixon learned from Sullivan something about the earlier CIA cover-up by Helms. And when Nixon said, 'It's likely to blow the whole Bay of Pigs' he might have been reminding Helms, not so gently, of the cover-up of the CIA assassination attempts on the hero of the Bay of Pigs, Fidel Castro - a CIA operation that may have triggered the Kennedy tragedy and which Helms desperately wanted to hide.

(4) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Challenging the Secret Government (1996)

On the morning of 11 February, a colleague whom Schorr considered a friend, Laurence Stern of the Washington Post, called to inform him that the Village Voice had published the Pike report that morning... Stern wanted to know if Schorr was the source, but Schorr was reluctant to reveal his role. The two journalists had a long conversation that wandered on and off the record. Despite Schorr's "sophistic evasions," the Post reporter eventually learned enough to identify the correspondent as the source of the report." The next morning, the Post identified Schorr not only as the purveyor of secret documents but also the lead actor in what it suggested was "a journalistic morality play".

(5) Daniel Schorr, Staying Tuned: A Life in Journalism (2001)

The disclosure that the CIA, in its domestic surveillance program code-named Operation Chaos, tapped wires and conducted break-ins caused a public stir that intervention in far-off Chile had not. Over the Christmas holiday in Vail, Colorado, President Ford, it would later emerge, had finally gotten to read the CIA inspector general's report, informally dubbed the Family Jewels.

It detailed a stunning list of 693 items of CIA malfeasance ranging from behavior-altering drug experiments on unsuspecting subjects, one of whom plunged to his death from a hotel window; to assassination plots against leftist third world leaders.

Anxious to keep congressional committees, already gearing up for investigations, from laying bare the worst of these, President Ford, on January 5, 1975, announced the appointment of a "blue-ribbon" commission to inquire into improper domestic operations. The panel was headed by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller and included such stalwarts as Gov. Ronald Reagan of California, retired general Lyman Lemnitzer, and former treasury secretary Douglas Dillon.

A few days later President Ford held a long-scheduled luncheon for New York Times publisher Arthur O. Sulzberger and several of his editors. Toward the end the subject of the newly named Rockefeller commission came up. Executive Editor A. M. Rosenthal observed that, dominated by establishment figures, the panel might not have much credibility with critics of the CIA. Ford nodded and explained that he had to he cautious in his choices because, with complete access to files, the commission might learn of matters, under presidents dating back to Truman, far more serious than the domestic surveillance they had been instructed to look into.

The ensuing hush was broken by Rosenthal. "Like what?"

"Like assassinations," the president shot back.

Prompted by an alarmed news secretary Ron Nessen, the president asked that his remark about assassinations be kept off the record.

The Times group returned to their bureau for a spirited argument about whether they could pass up a story potentially so explosive. Managing Editor E. C. Daniel called the White House in the hope of getting Nessen to ease the restriction from "off-the-record" to "deep background." Nessen was more adamant than ever that the national interest dictated that the president's unfortunate slip be forgotten. Finally, Sulzberger cut short the debate, saying that, as the publisher, he would decide, and he had decided against the use of the incendiary information.

This left several of the editors feeling quite frustrated, with the inevitable result that word of the episode began to get around, eventually reaching me. Under no off-the-record restriction myself, I enlisted CBS colleagues in figuring out how to pursue the story. Since Ford had used the word assassinations, we assumed we were looking for persons who had been murdered - possibly persons who had died under suspicious circumstances. We developed a hypothesis, but no facts.

On February 27, 1975, my long-standing request for another meeting with Director Colby came through. Over coffee we discussed Watergate and Operation Chaos, the domestic surveillance operation.

As casually as I could, I then asked, "Are you people involved in assassinations?"

"Not any more," Colby said. He explained that all planning for assassinations had been banned since the 1973 inspector general's report on the subject.

I asked, without expecting an answer, who had been the targets before 1973.

"I can't talk about it," Colby replied.

"Hammarskjold?" I ventured. (The UN. secretary-general killed in an airplane crash in Africa.)

"Of course not."

"Lumumba?" (The left-wing leader in the Belgian Congo who had been killed in 1961, supposedly by his Katanga rivals.)

"I can't go down a list with you. Sorry."

I returned to my office, my head swimming with names of dead foreign leaders who may have offended the American government. It was frustrating to be this close to one of the major stories of my career and not be able to get my hands on it. After a few days I decided I knew enough to go on the air even without the identity of corpses.

Because of President Ford's imprecision, I didn't realize that he was not referring to actual assassinations, but assassination conspiracies. All I knew was that assassination had been a weapon in the CIA arsenal until banned in a post-Watergate cleanup and that the president feared that investigation might expose the dark secret. l sat down at my typewriter and wrote, "President Ford has reportedly warned associates that if current investigations go too far they could uncover several assassinations of foreign officials involving the CIA..."

The two-minute "tell" story ran on the Evening News on February 28. While I had been mistaken in suggesting actual murders, my report opened up one of the darkest secrets in the CIA's history.

President Ford moved swiftly to head off a searching congressional investigation by extending the term of the Rockefeller commission and adding the assassination issue to its agenda. The commission hastily scheduled a new series of secret hearings in the vice president's suite in the White House annex. Richard Helms, who had already testified once, was called home again from his ambassador's post in Tehran for two days of questioning by the commission's staff and four hours before the commission on April 28.

I waited with colleagues and staked-out cameras outside the hearing room, the practice being to ask witnesses to make remarks on leaving. As Helms emerged, I extended my hand in greeting, with a jocular "Welcome back'." I was forgetting that I was the proximate reason for his being back.

His face ashen from fatigue and strain, he turned livid.

"You son of a bitch," he raged. "You killer, you cocksucker Killer Schorr - that's what they ought to call you!"

He then strode before the cameras and gave a toned-down version of his tirade. "I must say, Mr. Schorr, I didn't like what you had to say in some of your broadcasts on this subject. As far as I know, the CIA was never responsible for assassinating any foreign leader."

"Were there discussions of possible assassinations?" I asked.

Helms began losing his temper again. "I don't know when I stopped beating my wife, or you stopped beating your wife. Talk about discussions in government? There are always discussions about practically everything under the sun!"

I pursued Helms down the corridor and explained to him the presidential indiscretion that had led me to report "assassinations."

Calmer now, he apologized for his outburst and we shook hands. But because other reporters had been present, the story of his tirade was in the papers the next day.

(6) Daniel Schorr, Christian Science Monitor (15th July, 2005)

One stares at the calendar and searches for lessons to be learned. One lesson is the danger of falling into the "analogy trap" ... making new mistakes while trying to avoid repeating old ones.

Guided by analogies, we have lurched from syndrome to syndrome.

A generation of hawks was nurtured on the "no more Munichs" syndrome. Its symbol was British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the man with the umbrella who tried to satisfy Hitler's appetite by feeding him Czechoslovakia. Mr. Chamberlain promised "peace in our time," and his blunders led the world into total war in his time.

A generation of Americans who grew up on "no more Munichs" confronted Stalin, who replaced Hitler as the symbol of totalitarianism. These were the "best and brightest," collecting around President Kennedy, who had to live down his own appeaser father (Joseph Kennedy, who was the US ambassador to Britain from 1938 to 1940).

The "no more Munichs" syndrome - meaning block Soviet expansionism - gave us everything from Korea to the Bay of Pigs disaster to the Vietnam disaster.

Under the banner of anti-appeasement, America undertook to keep the dominoes from falling in Europe and Asia, and even in Guatemala and Nicaragua.

But it didn't work. There was no communist monolith, and Americans paid heavily for the slogan "no more Munichs."

Next, we had the "no more Vietnams" syndrome, a constant fear of being dragged into some quagmire. The "no more Vietnams" syndrome inhibited the US from acting in Somalia, Rwanda, and, for the first few years, in Afghanistan.

But not in Iraq. History may record that the Bush "Axis of Evil" syndrome marked the end of the "no more Vietnams" era.

An administration determined to transform the Middle East and foster democracy had no hesitation about invading Iraq on dubious grounds. Public support for that war seems now to be waning in the face of an insurgency of unexpected dimensions.

It may be too early to say, "No more Iraqs." But not too early to say that it may be time for a "no more syndromes" syndrome

(7) Daniel Schorr, Christian Science Monitor (15th July, 2005)

Let me remind you that the underlying issue in the Karl Rove controversy is not a leak, but a war and how America was misled into that war.

In 2002 President Bush, having decided to invade Iraq, was casting about for a casus belli. The weapons of mass destruction theme was not yielding very much until a dubious Italian intelligence report, based partly on forged documents (it later turned out), provided reason to speculate that Iraq might be trying to buy so-called yellowcake uranium from the African country of Niger. It did not seem to matter that the CIA advised that the Italian information was "fragmentary and lacked detail."

Prodded by Vice President Dick Cheney and in the hope of getting more conclusive information, the CIA sent Joseph Wilson, an old Africa hand, to Niger to investigate. Mr. Wilson spent eight days talking to everyone in Niger possibly involved and came back to report no sign of an Iraqi bid for uranium and, anyway, Niger's uranium was committed to other countries for many years to come.

No news is bad news for an administration gearing up for war. Ignoring Wilson's report, Cheney talked on TV about Iraq's nuclear potential. And the president himself, in his 2003 State of the Union address no less, pronounced: "The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa."

Wilson declined to maintain a discreet silence. He told various people that the president was at least mistaken, at most telling an untruth. Finally Wilson directly challenged the administration with a July 6, 2003 New York Times op-ed headlined, "What I didn't find in Africa," and making clear his belief that the president deliberately manipulated intelligence in order to justify an invasion.

One can imagine the fury in the White House. We now know from the e-mail traffic of Time's correspondent Matt Cooper that five days after the op-ed appeared, he advised his bureau chief of a super secret conversation with Karl Rove who alerted him to the fact that Wilson's wife worked for the CIA and may have recommended him for the Niger assignment. Three days later, Bob Novak's column appeared giving Wilson's wife's name, Valerie Plame, and the fact she was an undercover CIA officer. Mr. Novak has yet to say, in public, whether Mr. Rove was his source. Enough is known to surmise that the leaks of Rove, or others deputized by him, amounted to retaliation against someone who had the temerity to challenge the president of the United States when he was striving to find some plausible reason for invading Iraq.

The role of Rove and associates added up to a small incident in a very large scandal - the effort to delude America into thinking it faced a threat dire enough to justify a war.

(8) Godfrey Hodgson, The Guardian (26th July, 2005)

Daniel Schorr, who has died aged 93, belonged to the generation of American journalists who made their reputations in the early days of the cold war. He covered the Marshall plan and the building of the Berlin Wall. He was one of the classic "wear the trenchcoat as a badge of pride" generation of reporters who saw journalism not as a branch of the entertainment industry, but as a sacred cause. Ironically, it made him a celebrity.

More than 60 years later, he was still commenting, in his signature Bronx-accented baritone, on world affairs for America's National Public Radio. Though by then he was getting into the office with the help of a Zimmer frame, he taught himself to use a computer last December, and ended his last commentary only 11 days before he died, with characteristic professionalism. "Thank you," said his host, Scott Simon. And Schorr replied: "Any time!"

Schorr could be stubborn and pernickety, but he cherished a fierce integrity. He was forever in trouble, both with his subjects and his employers.

In 1976, he was fired by CBS, after 23 years, when he leaked the House of Representatives' Pike committee report on the CIA's misdeeds, including its attempts to murder Fidel Castro, to the Village Voice, the New York weekly newspaper. This opened up the historic inquisition into the agency's abuse of its powers. He was criticised by some for "dissembling" – his own word for it – and for allowing blame to fall for a time on his colleague Lesley Stahl. But he refused for the rest of his life to name his source.

At a public hearing, he refused to do so on grounds of the first amendment guarantee of press freedom, saying "to betray a source would mean to dry up many future sources for many future reporters ... It would mean betraying myself, my career and my life."

His greatest notoriety came when he was put on an "enemies' list" by President Richard Nixon, and his most dramatic moment when, having himself got hold of it, he read it out on air and found his own name at number 17. He froze and broke into a sweat, but succeeded in announcing his name with what looked like calm professionalism. He won three Emmys for his television reporting, but said in a 2009 interview, "I consider my presence on the enemies list a greater tribute than the Emmys list."