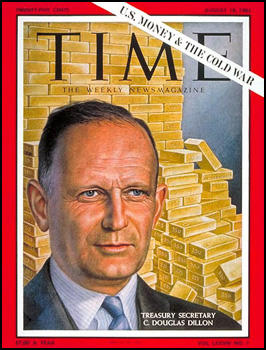

C. Douglas Dillon

Clarence Douglas Dillon was born in Geneva, Switzerland, on 21st August, 1909. His father, Clarence Dillon, was the head of a leading Wall Street investment firm.

After Dillon graduated from Harvard University in 1931 his father gave him $185,000 to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. In 1936 he became a director of United States and Foreign Securities Corporation. Two years later he became a Vice President and Director of Dillon, Read and Company.

Dillon saw active service in the United States Navy during the Second World War. During the last few months of the conflict he was in the Pacific and his ship survived several attacks by Japanese suicide bombers.

On his return from the war he became chairman of Dillon, Read and Company. A member of the Republican Party Dillon was a major contributor to the presidential campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower. In February 1953 Eisenhower appointed Dillon as his Ambassador to France. This created a great deal of controversy. As one journalist commented: "As a major contributor to President Eisenhower's 1952 campaign (and seemingly because his family owned the Haut-Brion vineyards in Bordeaux), he was made ambassador to France. Since he had no diplomatic experience and spoke execrable French, there was a predictable row about his appointment."

Dillon served as Ambassador to France until being appointed Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs in 1959. He was therefore responsible for the economic policies and programs of the Department of State and for coordinating the Mutual Security Program. Dillon attended several Foreign Ministers meetings. In 1959 he was one of the founders of the Inter-American Development Bank.

On the recommendation of Philip Graham President John F. Kennedy appointed Dillon as Secretary of the Treasury in January, 1961. Dillon was the United States spokesman for the Kennedy Administration's program of aid for the economic development of Latin America under the Alliance for Progress Program in 1961. The work continued under President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had pledged his support for continuing aid for the Alliance for Progress.

Dillon left office in April, 1965. Dillon continued to be a major contributor to the funds of the Republican Party. He also donated $20m to New York Metropolitan Museum. He helped raise another $100m for its refurbishment. He also served as chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation, was president of the Harvard board of overseers, chairman of the Brookings Institution and vice-chairman of the US council on foreign relations.

Clarence Douglas Dillon died on 10th January, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Katharine Graham, Personal History (1997)

Right after the election, he started talking to and writing the president-elect about appointments to the new administration. Both Phil and Joe Alsop thought Kennedy ought to appoint our friend Douglas Dillon as secretary of the Treasury. Dillon was a liberal Republican who had served as undersecretary of state in the Eisenhower administration and had contributed to the Nixon campaign, so this didn't seem like a strong possibility. Arthur Schlesinger and Ken Galbraith had dinner with us one evening, and, as Arthur noted in his book A Thousand Days, "we were distressed by (Phil's) impassioned insistence that Douglas Dillon should and would-be made Secretary of the Treasury. Without knowing Dillon, we mistrusted him on principle as a presumed exponent of Republican economic policies." But as Arthur also wrote, "When I mentioned this to the President-elect in Washington on December, he remarked of Dillon, "Oh, I don't care about those things. All I want to know is: is he able and will he go along with the program?'"

What a refreshing thought - if only more presidents felt that way! In fact, the president-elect called. Joe about the liberals wanting Albert Gore (father of the Clinton administration vice-president, Al Gore) for the position, but he told Joe that he wanted Dillon. Joe recalls Kennedy saying, "They say that if I take Doug Dillon he won't be loyal because he's a Republican." Joe responded that it would be very hard to imagine a man less likely to be disloyal than Dillon. He also added, "And if you take Albert Gore you know perfectly well, a) he's incompetent; b) you'll never be able to hear yourself think, he talks so much; c) when he isn't talking your ear off, he'll be telling the New York Times all." I'm sure this whole conversation with Kennedy was recalled in Alsopian terms, but I'm also sure that some such conversation did indeed take place.

(2) Harold Jackson, Douglas Dillon, The Guardian (24th February, 2004)

President-elect Kennedy was pragmatic about his choice of cabinet officers in December 1960. Warned that the man he wanted as treasury secretary had given large campaign contributions to his opponent Richard Nixon, Kennedy responded: "Oh, I don't care about those things. All I want to know is: is he able?"

And so Douglas Dillon, who has died aged 93, became the second Republican recruit to the new Democratic administration (the other was the defence secretary Robert McNamara). His selection was ensured once he told Kennedy that he would go quietly if he ever disagreed with administration policy.

The central economic issue facing Kennedy was the need to increase economic growth after the stagnant years of the Eisenhower administration; the new president wanted expansion to reach 5% a year. Dillon said that this could be achieved by aiming for "the largest deficit that will not frighten foreigners" - a figure he calculated at $5,000m a year. Since this was the best estimate of an already inescapable fiscal shortfall, it was a neat political judgment.

In public, however, Dillon constantly propounded the need to balance the US budget. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith later observed that the treasury secretary had managed to develop the best economic policy America had experienced for generations - but had only achieved it by acting like the courtesan "who, at any critical moment in the conversation, insists on the absolute importance of chastity".

The eventual outcome of Dillon's running deficit, which fluctuated between $3,900m and $6,300m, was significantly to exceed the Washington government's original growth target; it reached a consistent annual rate of 5.6%, and gave America what was then the longest peacetime expansion for a century. This ensured that even a die-hard Democrat like Lyndon Johnson would keep Dillon in office after Kennedy's assassination.