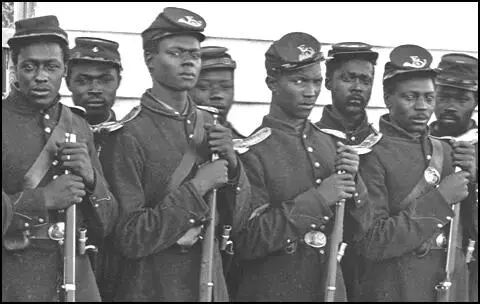

Black Regiments in the Civil War

On 15th April, 1861, Abraham Lincoln called on the governors of the Northern states to provide 75,000 militia to serve for three months to put down the insurrection. Some states responded well to Lincoln's call for volunteers. The governor of Pennsylvania offered 25 regiments, whereas Ohio provided 22. Most men were encouraged to enlist by bounties offered by state governments. This money attracted the poor and the unemployed. Many black Americans also attempted to join the army. However, the War Department quickly announced that it had "no intention to call into service of the Government any coloured soldiers." Instead, black volunteers were given jobs as camp attendants, waiters and cooks.

On 30th August, 1861, Major General John C. Fremont, commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. Abraham Lincoln was furious when he heard the news as he feared that this action would force slave-owners in border states to help the Confederates. Lincoln asked Fremont to modify his order and free only slaves owned by Missourians actively working for the South. When Fremont refused, he was sacked and replaced by General Henry Halleck.

In May, 1862, General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina. He was ordered to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) but eventually got approval from Congress for his action. Hunter also issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Abraham Lincoln quickly ordered Hunter to retract his proclamation as he still feared that this action would force slave-owners in border states to join the Confederates. However, unlike the case of Major General John C. Fremont in Missouri the previous year, Lincoln did not relieve him of his duties.

In January 1863 it was clear that state governors in the north could not raise enough troops for the Union Army. On 3rd March, the federal government passed the Enrollment Act. This was the first example of conscription or compulsory military service in United States history. The decision to allow men to avoid the draft by paying $300 to hire a substitute, resulted in the accusation that this was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight.

Abraham Lincoln was also now ready to give his approval to the formation of black regiments. He had objected in May, 1862, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers into the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment. However, nothing was said when Hunter created two more black regiments in 1863 and soon afterwards Lincoln began encouraging governors and generals to enlist freed slaves.

John Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts, and a passionate opponent of slavery, began recruiting black soldiers and established the 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Cavalry Regiment and the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) and the 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Infantry Regiments. In all, six regiments of US Colored Cavalry, eleven regiments and four companies of US Colored Heavy Artillery, ten batteries of the US Colored Light Artillery, and 100 regiments and sixteen companies of US Colored Infantry were raised during the war. By the end of the conflict nearly 190,000 black soldiers and sailors had served in the Union forces.

Primary Sources

(1) In July, 1862, the War Department decided that black soldiers would receive $7 a month, plus $3 for clothing. This compared to the $13 a month, plus $3.50 for clothing for white soldiers. On 28th September, 1863, Corporal James Henry Gooding, a black soldier in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, wrote to Abraham Lincoln about this act of discrimination.

We appeal to you, sir, as the executive of the nation, to have us justly dealt with. The regiment do pray that they be assured their service will be fairly appreciated by paying them as American soldiers, not as menial hirelings. Black men, you may well know, are poor; $3 per month, for a year, will supply their needy wives and little ones with fuel. If you, as chief magistrate of the nation, will assure us of our whole pay, we are content. Our patriotism, our enthusiasm will have a new impetus to exert our energy more and more to aid our country. Not that our hearts ever flagged in devotion, spite the evident apathy displayed on our behalf, but we feel as though our country spurned us, now we are sworn to serve her.

(2) Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Reminiscences (1892)

In the spring of 1863, I had another conversation with President Lincoln upon the subject of the employment of negroes. The question was, whether all the negro troops then enlisted and organized should be collected together and made a part of the Army of the Potomac and thus reinforce it.

We then talked of a favourite project he had of getting rid of the negroes by colonization, and he asked me what I thought of it. I told him that it was simply impossible; that the negroes would not go away, for they loved their homes as much as the rest of us, and all efforts at colonization would not make a substantial impression upon the number of negroes in the country.

Reverting to the subject of arming the negroes, I said to him that it might be possible to start with a sufficient army of white troops, and, avoiding a march which might deplete their ranks by death and sickness, to take in ships and land them somewhere on the Southern coast. These troops could then come up through the Confederacy, gathering up negroes, who could be armed at first with arms that they could handle, so as to defend themselves and aid the rest of the army in case of rebel charges upon it. In this way we could establish ourselves down there with an army that would be a terror to the whole South.

(3) Abraham Lincoln, letter to James C. Conking, defending his decision to emancipate slaves being held in the Deep South (26th August, 1863)

I know, as fully as one can know the opinions of others, that some of the commanders of our armies in the field who have given us our most important successes believe the emancipation policy and the use of the colored troops constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion, and that at least one of these important successes could not have been achieved when it was but for the aid of black soldiers. Among the commanders holding these views are some who have never had any affinity with what is called Abolitionism or with the Republican Party politics, but who hold them purely as military opinions.

(4) Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

The downfall of the Confederacy left more than three million black people free under the Proclamation of the President,

but without ground enough to stand upon. They were congregated in large camps or remained in little slave-huts under the shadow of their former masters' mansions, and continued to toil, in most cases with the promise of some compensation. No one could tell what their status would be in the future. The black population of the country had furnished nearly two hundred thousand men who served in the Union army and navy, and who performed their duty with fidelity and fortitude. Their dead and wounded fell on many hard-fought fields, notwithstanding the threat of the enemy, of no quarter for the officers and slavery for the men in case of capture. Although at the close of the war many believed that free labor would be a failure in the South, yet it has proved a success. It has furnished the principal labor element in those States for the development of the great resources of that part of our country. No one can tell what is to be the future of a race that has nearly trebled its numbers in the last four decades, and in point of education, general intelligence, and acquired property, has vastly exceeded its increase in numbers. The great problem is yet to be solved, but its solution will be best accomplished if absolute even-handed justice prevails. The race is not responsible for its being here, nor for its present condition. Its future will depend largely upon its own people.

(5) Harper's Weekly, (30th April, 1864)

On the 12th April, the rebel General Forrest appeared before Fort Pillow, near Columbus, Kentucky, attacking it with considerable vehemence. This was followed up by frequent demands for its surrender, which were refused by Major Booth, who commanded the fort. The fight was then continued up until 3 p.m., when Major Booth was killed, and the rebels, in large numbers, swarmed over the intrenchments. Up to that time comparatively few of our men had been killed; but immediately upon occupying the place the rebels commenced an indiscriminate butchery of the whites and blacks, including the wounded. Both white and black were bayoneted, shot, or sabred; even dead bodies were horribly mutilated, and children of seven and eight years, and several negro women killed in cold blood. Soldiers unable to speak from wounds were shot dead, and their bodies rolled down the banks into the river. The dead and wounded negroes were piled in heaps and burned, and several citizens, who had joined our forces for protection, were killed or wounded. Out of the garrison of six hundred only two hundred remained alive. Three hundred of those massacred were negroes; five were buried alive. Six guns were captured by the rebels, and carried off, including tow 10-pound Parrotts, and two 12-pound howitzers. A large amount of stores was destroyed or carried away.

(6) Harper's Weekly, (18th February, 1865)

With a fine tact of simple honesty the President, in his little speech at the opening of the Fair in Baltimore, said exactly what we all wished to hear. The massacre at Fort Pillow had raised the question in every mind, does the United States mean to allow its soldiers to be butchered in cold blood? The President replies, that whoever is good enough to fight for us is good enough to be protected by us: and that in this case, when the facts are substantiated, there shall be retaliation. In what way we can retaliate it is not easy to say.

There is no evidence from Richmond, and there will be none, that Forrest’s murders differ from those of Quantrell. On the other hand, we must not forget that the same papers which brought the President’s speech promising retaliation brought us also the return of the rebel General in Florida, containing, for the relief of friends at home, the names and injuries of our wounded men in his hands, and the list included the colored soldiers of the Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth Massachusetts regiments. But if public opinion has justified a stronger policy from the beginning - if the criminally stupid promises of M’Clellan and Halleck to protect slavery and to repel the negroes coming to our lines had never been made, we should not now be confronted with this question, because the rebels would never have dared to massacre our soldiers after surrender. But yet to be deterred from retaliation from fear of still further crimes upon the part of the rebels is simple inhumanity.

Let us either at once release every colored soldier and the officer of their regiments from duty, or make the enemy feel that they are our soldiers. It is very sad that rebel prisoners of war should be shot for the crimes of Forrest. But it is very sad, no less, that soldiers fighting for our flag have been buried alive after surrendering, and it is still sadder that such barbarities should be encouraged by refraining from retaliation. Do we mean to allow Mr. Jefferson Davis, or this man Forrest, or Quantrell, to dictate who shall, and who shall not, fight for the American flag? The massacre at Fort Pillow is a direct challenge to our Government to prove whether it is in earnest or not in emancipating slaves and employing colored troops. There should be no possibility of mistake in the reply. Let the action of the Government be as prompt and terrible as it will be final. Then the battles of this campaign will begin with the clear conviction upon the part of the rebels that we mean what we say; and that the flag will protect to the last, and by every means of war, including retaliation of blood, every soldier who fights for us beneath it.