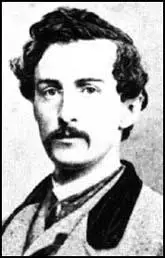

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth was born in Bel Air, Maryland, on 10th May, 1838. He was the ninth of ten children born to the famous actor, Junius Brutus Booth.

Booth made his acting debut at the age of seventeen in Baltimore. He toured throughout America and soon became one of America's leading actors and was especially acclaimed for the work he did with the Shakespearean company that was based in Richmond.

Unlike the rest of his family, Booth was an ardent supporter of slavery. In 1859 he joined the Virginia militia company that assisted in the capture of John Brown at Harper's Ferry.

Although Booth had a deep hatred for President Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, he did not join the Confederate Army on the outbreak of the American Civil War. Instead he worked as a secret agent and also helped to smuggle medical supplies from the North to the Confederate forces in the South. As a touring actor Booth had the perfect cover for this work.

In 1864 Booth devised a scheme to kidnap Abraham Lincoln in Washington. The plan was to take Lincoln to Richmond and hold him until he could be exchanged for Confederate Army prisoners of war. Others involved in the plot included Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, John Surratt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin and Samuel Arnold. Booth decided to carry out the deed on 17th March, 1865 when Lincoln was planning to attend a play at the Seventh Street Hospital that was situated on the outskirts of Washington. The kidnap attempt was abandoned when Lincoln decided at the last moment to cancel his visit.

On 9th April, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Two days later Booth attended a public meeting in Washington where he heard Abraham Lincoln make a speech where he explained his views that voting rights should be granted to some African Americans. Booth was furious and decided to assassinate the president before he could carry out these plans.

Booth persuaded most of the people who had been involved in the kidnap plot to join him in his plan. Booth discovered that on 14th April, Abraham Lincoln was planning to attend the evening performance of Our American Cousin at the Ford Theatre in Washington. Booth decided he would assassinate Lincoln while George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward. All attacks would take place at approximately 10.15 p.m. that night.

Booth, armed with a derringer pistol and a hunting knife, arrived at the theatre at about 9.30 p.m. John Burroughs, a boy who worked at the theatre, was asked to hold his horse while he went to a nearby saloon for a drink. He entered Ford's Theatre soon after 10.00 p.m. and made his way to the State Box. John Parker, Lincoln's bodyguard from the Metropolitan Police Force, had left his position outside the State Box to get a drink. Inside was Abraham Lincoln, his wife Mary Lincoln, and two friends, Major Henry Rathbone and his future wife, Clara Harris.

At 10.15 p.m. Booth entered the State Box and shot Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. When Rathbone attempted to grab Booth he was slashed with the hunting knife. Booth then jumped about 11 feet onto the stage below. He landed badly and snapped the fibula bone in his left leg just above the ankle. Booth waving his hunting knife at the audience, hobbled outside and got on his horse and rode out of the city.

Meanwhile Lewis Powell had attacked William Seward in his house. Although badly wounded, he survived. George Atzerodt, lost his nerve, and never made his assassination attempt on Andrew Johnson. The plan was for the conspirators to meet at the boarding house owned by Mary Surratt in Surrattsville, Maryland. After a brief stop to pick up supplies Booth and David Herold left and headed for the Deep South.

At 4.00 a.m. Booth and Herold arrived at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd who treated Booth's broken leg. With the help of other sympathizers they reached Port Royal, Virginia, on the morning of 26th April. They hid in a barn owned by Richard Garrett. However, federal troops arrived soon afterwards and the men were ordered to surrender.

David Herold came out of the barn but Booth refused and so the barn was set on fire. While this was happening one of the soldiers, Sergeant Boston Corbett, found a large crack in the barn and was able to shoot Booth in the back. His body was dragged from the barn and after being searched the soldiers recovered his leather bound diary. The bullet had punctured his spinal cord and he died in great agony two hours later.

On 29th June, 1865 Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Surratt, who was expected to be reprieved, was the first woman in American history to be executed.

Primary Sources

(1) John Surratt, lecture on the Abraham Lincoln conspiracy at Rockville, Maryland (6th December, 1870)

In the fall of 1864 I was introduced to John Wilkes Booth, who, I was given to understand, wished to know something about the main avenues leading from Washington to the Potomac. We met several times, but as he seemed to be very reticent with regard to his purposes, and very anxious to get all the information out of me he could, I refused to tell him anything at all. At last I said to him, "It is useless for you, Mr. Booth, to seek any information from me at all; I know who you are and what are your intentions." He hesitated some time, but finally said he would make known his views to me provided I would promise secrecy. I replied, "I will do nothing of the kind. You know well I am a Southern man. If you cannot trust me we will separate." He then said, "I will confide my plans to you; but before doing so I will make known to you the motives that actuate me. In the Northern prisons are many thousands of our men whom the United States Government refuses to exchange. You know as well as I the efforts that have been made to bring about that much desired exchange. Aside from the great suffering they are compelled to undergo, we are sadly in want of them as soldiers. We cannot spare one man, whereas the United States Government is willing to let their own soldiers remain in our prisons because she has no need of the men. I have a proposition to submit to you, which I think if we can carry out will bring about the desired exchange."

There was a long and ominous silence which I at last was compelled to break by asking, "Well, Sir, what is your proposition?" He sat quiet for an instant, and then, before answering me, arose and looked under the bed, into the wardrobe, in the doorway and the passage, and then said, "We will have to be careful; walls have ears." He then drew his chair close to me and in a whisper said, "It is to kidnap President Lincoln, and carry him off to Richmond!" "Kidnap President Lincoln!" I said. I confess that I stood aghast at the proposition, and looked upon it as a foolhardy undertaking. To think of successfully seizing Mr. Lincoln in the capital of the United States surrounded by thousands of his soldiers, and carrying him off to Richmond, looked to me like a foolish idea. I told him as much. He went on to tell with what facility he could be seized in various places in and about Washington. As for example in his various rides to and from the Soldiers' Home, his summer residence. He entered into the minute details of the proposed capture, and even the various parts to be performed by the actors in the performance.

I was amazed - thunderstruck - and in fact, I might also say, frightened at the unparalleled audacity of this scheme. After two days' reflection I told him I was willing to try it. I believed it practicable at that time, though I now regard it as a foolhardy undertaking. I hope you will not blame me for going thus far. I honestly thought an exchange of prisoners could be brought about could we have once obtained possession of Mr. Lincoln's person. And now reverse the case. Where is there a young man in the North with one spark of patriotism in his heart with would not have with enthusiastic ardor joined in any undertaking for the capture of Jefferson Davis and brought him to Washington? There is not one who would not have done so. And so I was led on by a sincere desire to assist the South in gaining her independence. I had no hesitation in taking part in anything honorable that might tend toward the accomplishment of that object. Such a thing as the assassination of Mr. Lincoln I never heard spoken of by any of the party. Never.

(2) Just before his death Louis Weichmann wrote an account of going with John Wilkes Booth to see Abraham Lincoln make a speech in Washington in 1865.

The President was his usual stature and erect self. I had never seen Mr. Lincoln up close and I knew he was a tall man however nothing could have prepared me for the sight of him. A long shadow did he have. And his arms, when at his sides, touched near his knees. Very professionally he said that there would never be any suffrage based on differences in the way people look. Upon this, Booth turned to the two of us and said, “That means n***** citizenship. Now by God I’ll put him through!”

(3) Major Henry Rathbone, testimony at the Military Tribunal investigating the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (15th May, 1865)

When the second scene of the third act was being performed, and while I was intently observing the proceedings upon the stage, with my back toward the door, I heard the discharge of a pistol behind me, and, looking round, saw through the smoke a man between the door and the President. The distance from the door to where the President sat was about four feet. At the same time I heard the man shout some word, which I thought was "Freedom!" I instantly sprang toward him and seized him. He wrested himself from my grasp, and made a violent thrust at my breast with a large knife. I parried the blow by striking it up, and received a wound several inches deep in my left arm, below the elbow and the shoulder. The orifice of the wound was about an inch and a half in length, and extended upward toward the shoulder several inches. The man rushed to the front of the box, and I endeavored to seize him again, but only caught his clothes as he was leaping over the railing of the box.

(4) Joseph Stewart was a member of the audience who attempted to capture John Wilkes Booth. He gave evidence against Edman Spangler at his trial on 25th May, 1865.

I was at Ford's Theater on the night of the assassination of the President. I was sitting in the front-seat of the orchestra, on the right-hand side. The sharp report of a pistol at about half-past 10 startled me. I heard an exclamation, and simultaneously a man leaped from the President's box, lighting on the stage. He came down with his back slightly toward the audience, but rising and turning, his face came in full view. At the same instant I jumped on the stage, and the man disappeared at the left-hand stage entrance. I ran across the stage as quickly as possible, following the direction he took, calling out, "Stop that man!" three times.

Near the door on my right hand, I saw a man (Spangler) standing, who seemed to be turning, and who did not seem to be moving about like the others. I am satisfied that the person I saw inside the door was in a position and had an opportunity, if he had been disposed to do so, to have interrupted the exit of Booth.

(5) Boston Corbett, testimony before the Military Tribunal investigating the death of Abraham Lincoln (17th May, 1865)

After making inquiries at the house, it was found that Booth was in the barn. After being ordered to surrender, and told that the barn would be fired in five minutes if he did not do so, Booth made many replies. He wanted to know who we took him for; he said his leg was broken; and what did we want with him; and he was told that it made no difference. The parley lasted much longer than the time first set; probably a full half hour; but he positively declared that he would not surrender.

After a while we heard the whispering of another person - although Booth had previously declared that there was no one there but himself - who proved to be the prisoner Herold. Although we could not distinguish the words, Herold seemed to be trying to persuade Booth to surrender. Then Booth said, "Oh, go out and save yourself, my boy, if you can;" and then said, "I declare before my Maker that this man here is innocent of any crime whatever."

Immediately after Herold was taken out, the detective Mr. Conger, came round to the side of the barn where I was and set fire to hay through one of the cracks. In front of me was a large crack in the barn. I saw him make a movement toward the door. I supposed he was going to fight his way out. He was taking aim with the carbine. I took steady aim of my arm, and shot him through the large crack in the barn. He lived, I should think, until about 7 o'clock that morning; perhaps two or three hours after he was shot.

(6) Captain Edward Doherty, testimony before the Military Tribunal investigating the death of Abraham Lincoln (22nd May, 1865)

We requested Booth and Herold to come out of the barn. Herold eventually surrendered. I searched him and found a map of Virginia. Just at this time the shot was fired and the door thrown open, and I dragged Herold into the barn with me. Booth had fallen on his back. The soldiers went into the barn and carried out Booth. I took Herold and tied him by the hands to a tree opposite, about two yards from where Booth's body was carried, on the verandah of the house, and kept him there until we were ready to return. Booth in the mean time died.

(7) Robert Garrett, who witnessed the killing of John Wilkes Booth was interviewed by H. G. Howard in his book Civil War Echoes (1907)

Through the cracks could be seen the form of Booth standing in the middle of the building, supported by his crutch. In his hands he held a carbine. At this instant, Sergeant Corbett fired through a crack in the wall. He said afterward that Booth had a gun to his shoulder and was about to kill one of the officers. This is not so, as I was standing within six feet of Corbett when he fired the shot, and Booth never made a motion to shoot.