Mary Surratt

Mary Jenkins was born in in Waterloo, Maryland, in May, 1823. Educated at a Catholic female seminary in Alexandria, Virginia, she married John Harrison Surratt when she was seventeen. The couple went to live on land that he had inherited just outside of Washington at Oxon Hill. In 1851 a fire destroyed their home the couple decided to rebuild a combined home and tavern.

In 1853 Surratt purchased 287 acres of farmland in Prince George's County. He built a tavern and post office and the community eventually became known as Surrattsville. Surratt worked as the local postmaster until his death on 25th August, 1862.

In October, 1864, Mrs. Surratt decided to rent the Surrattsville property for $500 a year to an ex-policeman, John M. Lloyd, and moved to a house she owned at 541 High Street, Washington. To make some extra money she rented out some of her rooms.

During the American Civil War, her eldest son, John Harrison Surratt, joined the Confederate Army. Her other son, John Surratt, worked as an agent for the Confederacy. He met others working as secret agents including John Wilkes Booth who stayed at the Surratt's boardinghouse when he was in the area. It is not known if Mrs. Surratt knew if these men were working for the Confederacy.

On the 17th April, police officers arrived at Mrs. Surratt's boardinghouse. Lewis Powell was also at the house and the two of them were arrested and charged with conspiring to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. When the police searched the house they found a hidden photograph of John Wilkes Booth, the man who had assassinated Lincoln at Ford's Theatre on 14th April.

Louis Weichmann, one of Mrs. Surratt's borders, and John M. Lloyd, the man who rented the tavern at Surrattsville, were also arrested and threatened with being charged with the murder of Abraham Lincoln. Kept in solitary confinement both men eventually agreed to give evidence against Mrs. Surratt in return for their freedom.

On 1st May, 1865, President Andrew Johnson ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators. It was argued by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, that the men should be tried by a military court as Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the army. Several members of the cabinet, including Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy), Edward Bates (Attorney General), Orville H. Browning (Secretary of the Interior), and Henry McCulloch (Secretary of the Treasury), disapproved, preferring a civil trial. However, James Speed, the Attorney General, agreed with Stanton and therefore the defendants did not enjoy the advantages of a jury trial.

The trial began on 10th May, 1865. The military commission included leading generals such as David Hunter, Lewis Wallace, Thomas Harris and Alvin Howe and Joseph Holt was the government's chief prosecutor. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were all charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. During the trial Holt attempted to persuade the military commission that Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government had been involved in conspiracy.

Joseph Holt attempted to obscure the fact that there were two plots: the first to kidnap and the second to assassinate. It was important for the prosecution not to reveal the existence of a diary taken from the body of John Wilkes Booth. The diary made it clear that the assassination plan dated from 14th April. The defence surprisingly did not call for Booth's diary to be produced in court.

At the trial John M. Lloyd told the court that on the Tuesday before the assassination Mrs. Surratt and Louis Weichmann visited him. Lloyd claimed that Mrs. Surratt "told me to have those shooting-irons ready that night, there would be some parties who would call for them. She gave me something wrapped in a piece of paper, which I took up stairs, and found to be a field-glass. She told me to get two bottles of whisky ready, and that these things were to be called for that night."

When Louis Weichmann testified he told the court that he had seen John Wilkes Booth, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt and David Herold in Mrs. Surratt's house together. This supported the prosecution's claim that the boarding house was where the assassination plot had been planned.

Weichmann also testified that as far as he knew Mrs. Surratt was not disloyal to the Union cause. A large number of friends and neighbours also appeared in court and stressed that they had never head her express support for the Confederacy.

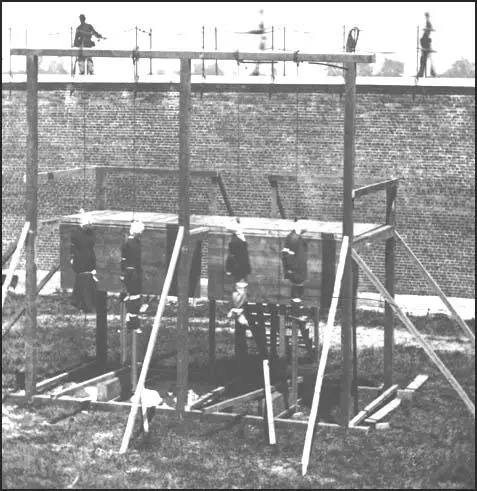

George Atzerodt at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865.

On 29th June, 1865, Mrs. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were all sentenced to be hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865.

Five out of the nine members of the Military Commission, recommended that Mrs. Surratt be shown mercy "due to her sex and age". President Andrew Johnson was later to say he was never told this and he gave the order to hang the woman who he pointed out "kept the nest that hatched the egg".

On 7th July, 1865, Mary Surratt, still pleading her innocence, became the first woman in American history to be executed by the federal government.

Primary Sources

(1) Louis Weichmann, testimony before the Military Tribunal (13th May, 1865)

On Friday, the day of the assassination, I went to Howard’s stable, about half-past 2 o’clock, having been sent there by Mrs. Surratt for the purpose of hiring a buggy. I drove her to Surrattsville the same day, arriving there about half-past 4. We stopped at the house of Mr. Lloyd, who keeps a tavern there. Mrs. Surratt went into the parlor. I remained outside a portion of the time, and went into the bar-room a part of the time, until Mrs. Surratt sent for me. We left about half-past 6. Surrattsville is about a two-hour drive to the city, and is about ten miles from the Navy Yard bridge. Just before leaving the city, as I was going to the door, I saw Mr. Booth in the parlor, and Mrs. Surratt was speaking with him. They were alone.

Some time in March last, I think, a man calling himself Wood came to Mrs. Surratt’s and inquired for John H. Surratt. I went to the door and told him Mr. Surratt was not at home; he thereupon expressed a desire to see Mrs. Surratt, and I introduced him, having first asked his name. That is the man (pointing to Lewis Powell). He stopped at the house all night. He had supper served up to him in my room; I took it to him from the kitchen. He brought no baggage; he had a black overcoat on, a black dress-coat, and gray pants. He remained till the next morning, leaving by the earliest train for Baltimore. About three weeks afterward he called again, and I again went to the door. I had forgotten his name, and, asking him, he gave the name of Powell I ushered him into the parlor, where were Mrs. Surratt, Miss Surratt, and Miss Honora Fitzpatrick. He remained three days that time. He represented himself as a Baptist preacher; and said that he had been in prison for about a week; that he had taken the oath of allegiance, and was now going to become and good and loyal citizen. Mrs. Surratt and her family are Catholics. John H. Surratt is a Catholic, and was a student of divinity at the same college as myself. I heard no explanation given why a Baptist preacher should seek hospitality at Mrs. Surratt’s; they only looked upon it as odd, and laughed at it. Mrs. Surratt herself remarked that he was a great looking Baptist preacher.

I met the prisoner, David E. Herold, at Mrs. Surratt’s on one occasion; I also met him when we visited the theater when Booth played Pescara; and I met him at Mrs. Surratt’s, in the country, in the spring of 1863, when I first made Mrs. Surratt’s acquaintance. I met him again in the summer of 1864, at Piscataway Church. These are the only times, to my recollection, I ever met him. I do not know either of the prisoners, Arnold or O’Laughlin.

(2) Major H. W. Smith, testimony before the Military Tribunal (19th May, 1865)

I was in charge of the party that took possession of Mrs. Surratt’s house, 541 High Street, on the night of the 17th of April, and arrested Mrs. Surratt, Miss Surratt, Miss Fitzpatrick, and Miss Jenkins. When I went up the steps, and rang the bell of the house, Mrs. Surratt came to the window, and said "Is that you, Mr. Kirby?" The reply was that it was not Mr. Kirby, and to open the door. She opened the door, and I asked, "Are you Mrs. Surratt?" She said, "I am the widow of John H. Surratt." And I added, "The mother of John H. Surratt, jr.?" She replied, "I am." I then said, "I come to arrest you and all in your house, and take you for examination to General Augur’s headquarters." No inquiry whatever was made as to the cause of the arrest. While we were there, Powell came to the house. I questioned him in regard to his occupation, and what business he had at the house that time of night. He stated that was a laborer, and had come there to dig a gutter at the request of Mrs. Surratt. I went to the parlor door, and said, "Mrs. Surratt, will you step here a minute?" She came out, and I asked her, "Do you know this man, and did you hire him to come and dig a gutter for you?" She answered, raising her right hand, "Before God, sir, I do not know this man, and have never seen him, and I did not hire him to dig a gutter for me." Powell said nothing. I then placed him under arrest, and told him he was so suspicious a character that I should send him to Colonel Wells, at General Augur’s headquarters, for further examination. Powell was standing in full view of Mrs. Surratt, and within three paces of her, when she denied knowing him.

(3) George Cottingham, testimony before the Military Tribunal (25th May, 1865)

I am special officer on Major O’Beirne’s force, and was engaged in making arrests after the assassination. After the arrest of John M. Lloyd by my partner, he was placed in my charge at Roby’s Post-office, Surrattsville. For the two days after his arrest Mr. Lloyd denied knowing any thing about the assassination. I told him that I was perfectly satisfied he knew about it, and had a heavy load on his mind, and that the sooner he got rid of it the better. He then said to me, "O, my God, if I was to make a confession, they would murder me!" I asked, "Who would murder you?" He replied, "These parties that are in this conspiracy." "Well, said I, "if you are afraid of being murdered, and let these fellows get out of it, that is your business, not mine." He seemed to be very much excited.

Lloyd stated to me that Mrs. Surratt had come down to his place on Friday between 4 and 5 o’clock; that she told him to have the fire-arms ready; that two men would call for them at 12 o’clock, and that two men did call; that Herold dismounted from his horse, went into Lloyd’s tavern, and told him to go up and get those fire-arms. The fire-arms, he stated, were brought down; Herold took one, and Booth’s carbine was carried out to him; but Booth said he could not carry his, it was as much as he could do to carry himself, as his leg was broken. Then Booth told Lloyd, "I have murdered the President;" and Herold said "I have fixed off Seward." He told me this on his way to Washington, with a squad of cavalry; I was in the house when he came in. He commenced crying and hallooing out, "O, Mrs. Surratt, that vile woman, she has ruined me! I am to be shot! I am to be shot!"

I asked Lloyd where Booth’s carbine was; he told me it was up stairs in a little room; where Mrs. Surratt kept some bags. I went up into the room and hunted about, but could not find it. It was at last found behind the plastering of the wall. The carbine was in a bag, and had been suspended by a string tied round the muzzle of the carbine; the string had broken, and the carbine had fallen down.

(4) John M. Lloyd, testimony before the Military Tribunal (13th May, 1865)

I reside at Mrs. Surratt's tavern, Surrattsville, and am engaged in hotel-keeping and farming. Some five or six weeks before the assassination of the President, John H. Surratt, David E. Herold, and G. A. Atzerodt came to my house. All three, when they came into the bar-room, drank, I think. John Surratt then called me into the front parlor, and on the sofa were two carbines, with ammunition; also a rope from sixteen to twenty feet in length, and a monkey wrench. Surratt asked me to take care of these things, and to conceal the carbines. I told him there was no place to conceal them, and I did not wish to keep such things. He then took me to a room I had never been in, immediately above the store-room, in the back part of the building. He showed me where I could put them underneath the joists of the second floor of the main building. I put them in there according to his directions.

I stated to Colonel Wells that Surratt put them there, but I carried the arms up and put them in there myself. There was also one cartridge-box of ammunition. Surratt said he just wanted these articles to stay for a few days, and he would call for them. On the Tuesday before the assassination of the President, I was coming to Washington, and I met Mrs. Surratt, on the road, at Uniontown. When she first broached subject to me about the articles at my place, I did not know what she had reference to. Then she came out plainer, and asked me about the "shooting-irons." I had myself forgotten about them being there. I told her they were hid away far back, and that I was afraid the house might be searched. She told me to get them out ready; that they would be wanted soon. I do not recollect distinctly the first question she put to me. Her language was indistinct, as if she wanted to draw my attention to something, so that no one else would understand. Finally she came out bolder with it, and said they would be wanted soon. I told her that I had an idea of having them buried; that I was very uneasy about having them there.

On the 14th of April I went to Marlboro to attend a trial there; and in the evening, when I got home, which I should judge was about 5 o'clock, I found Mrs. Surratt there. She met me out by the wood-pile as I drove in with some fish and oysters in my buggy. She told me to have those shooting-irons ready that night, there would be some parties who would call for them. She gave me something wrapped in a piece of paper, which I took up stairs, and found to be a field-glass. She told me to get two bottles of whisky ready, and that these things were to be called for that night.

Just about midnight on Friday, Herold came into the house and said, "Lloyd, for God's sake, make haste and get those things." I did not make any reply, but went straight and got the carbines, supposing they were the parties Mrs. Surratt had referred to, though she didn't mention any names. From the way he spoke he must have been apprised that I already knew what I was to give him. Mrs. Surratt told me to give the carbines, whisky, and field-glass. I did not give them the rope and monkey-wrench. Booth didn't come in. I did not know him; he was a stranger to me. He remained on his horse. Herold, I think, drank some out of the glass before he went out.

I do not think they remained over five minutes. They only took one of the carbines. Booth said he could not take his, because his leg was broken. Just as they were about leaving, the man who was with Herold said, "I will tell you some news, if you want to hear it," or something to that effect. I said, "I am not particular; use your own pleasure about telling it." "Well, said he, "I am pretty certain that we have assassinated the President and Secretary Seward."

(5) General David Hunter and the Military Commission that tried the Lincoln conspirators sent a message to President Andrew Johnson about the case of Mary Surratt (29th June, 1865)

The undersigned members of the Military Commission detailed to try Mary E. Surratt and others for the conspiracy and the murder of Abraham Lincoln, late President of the United States, do respectively pray the President, in consideration of the sex and age of the said Mary E. Surratt, if he can upon all the facts in the case, find it consistent with his sense of duty to the country to commute the sentence of death to imprisonment in the penitentiary for life.

(6) The New York Sun (21st December, 1892)

Although Lloyd's testimony was most damaging against Mrs. Surratt, and probably condemned her, he himself never believed in Mrs. Surratt's guilt, and said she was a victim of circumstances. Her association with the real conspirators, he always held, was the cause of her conviction.

(7) General Thomas Harris, letter to the The New York Sun (4th August, 1901)

It must be remembered that on the night of 17th April (1865) Powell returned to her house, with pick-axe on the shoulder and cap made from his shirt sleeve on his head.

The very act of this red-handed murderer fleeing to her home at such a time, was in itself, the strongest and most damning evidence against her.

Take away these two items of evidence - the terrible story of the shooting irons and Payne's return, wipe them out, remove them for the record, and Mr. Weichmann's evidence as to what he saw and heard in Mrs. Surratt's house falls harmlessly to the ground.

(8) Captain Christian Rath, was placed in charge of the execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold. He was later interviewed about his role in the event.

I was determined to get rope that would not break, for you know when a rope breaks at a hanging there is a time-worn maxim that the person intended to be hanged was innocent. The night before the execution I took the rope to my room and there made the nooses. I preserved the piece of rope intended for Mrs. Surratt for the last.

I had the graves for the four persons dug just beyond the scaffolding. I found some difficulty in having the work done, as the arsenal attaches were superstitious. I finally succeeded in getting soldiers to dig the holes but they were only three feet deep.

The hanging gave me a lot of trouble. I had read somewhere that when a person was hanged his tongue would protrude from his mouth. I did not want to see four tongues sticking out before me, so I went to the storehouse, got a new white shelter tent and made four hoods out of it. I tore strips of the tent to bind the legs of the victims.

(9) William Coxshall, a member of the Veteran Reserve Corps, was assigned the task of dropping the trapdoor on the left side of the gallows.

The prison door opened and the condemned came in. Mrs. Surratt was first, near fainting after a look at the gallows. She would have fallen had they not supported her. Herold was next. The young man was frightened to death. He trembled and shook and seemed on the verge of fainting. Atzerodt shuffled along in carpet slippers, a long white nightcap on his head. Under different circumstances, he would have been ridiculous.

With the exception of Powell, all were on the verge of collapse. They had to pass the open graves to reach the gallows steps and could gaze down into the shallow holes and even touch the crude pine boxes that were to receive them. Powell was as stolid as if he were a spectator instead of a principal. Herold wore a black hat until he reached the gallows. Powell was bareheaded, but he reached out and took a straw hat off the head of an officer. He wore it until they put the black bag on him. The condemned were led to the chairs and Captain Rath seated them. Mrs. Surratt and Powell were on our drop, Herold and Atzerodt on the other.

Umbrellas were raised above the woman and Hartranft, who read the warrants and findings. Then the clergy took over talking what seemed to me interminably. The strain was getting worse. I became nauseated, what with the heat and the waiting, and taking hold of the supporting post, I hung on and vomited. I felt a little better after that, but not too good.

Powell stood forward at the very front of the droop. Mrs. Surratt was barely past the break, as were the other two. Rath came down the steps and gave the signal. Mrs. Surratt shot down and I believed died instantly. Powell was a strong brute and died hard. It was enough to see these two without looking at the others, but they told us both died quickly.