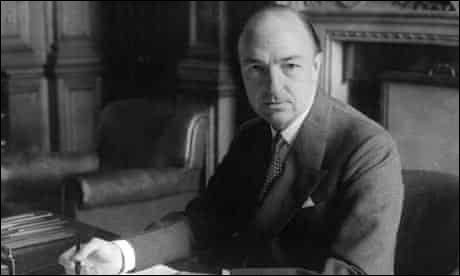

John Profumo

John Profumo, the son of Albert Profumo, was born on 30th January 1915. The Profumo family made their fortune in insurance and by the outbreak of the First World War held a controlling interest in Provident Life.

Profumo was educated at Harrow and Brasenose College, Oxford, he became a member of the Conservative Party and by the age of 21 he was chairman of the Fulham Conservative Association. In May 1939 he was adopted as Conservative candidate for Kettering, but on the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry.

In 1940 there was an unexpected by-election at Kettering, and at the age of 25 he became the youngest MP in the House of Commons. However, the result caused a sensation as a Workers and Pensioners Anti-War candidate polled 27 per cent of the vote. On 8th May 1940 Profumo, along with 30 Conservative MPs, joined forces with the Labour Party to vote against the government's handling of Nazi Germany. As a result of this vote Neville Chamberlain was forced to resign and was replaced by Winston Churchill as prime minister.

Profumo had a distinguished military career, being mentioned in dispatches during the North Africa campaign. He served with Field Marshal Harold Alexander in Italy. He was later appointed Brigadier and Chief of Staff to the British Liaison Mission to General Douglas MacArthur in Japan. Profumo also landed in Normandy on D-Day with an armoured brigade, and took part in the fighting at Caen.

Profumo lost his seat in the 1945 General Election. He obtained a post at Conservative Central Office as the party's broadcasting adviser. Profumo was returned to the House of Commons as MP for Stratford-on-Avon in the 1950 General Election. Two years later he was appointed a junior minister at the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation.

In 1957 Profumo was appointed Parliamentary Under Secretary to the Colonies and subsequently Minister of State for Foreign Affairs. In 1960 Harold Macmillan appointed Profumo as his Secretary of State for War.

On 8th July 1961 Profumo met Christine Keeler, at a party at Cliveden. Profumo kept in contact with Keeler and they eventually began an affair. At the same time Keeler was also sleeping with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler: "Their (Ward and Hollis) plan was simple. I was to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany."

During this period she became involved with two black men, Lucky Gordon and John Edgecombe. The two men became jealous of each other and this resulted in Edgecombe slashing Gordon's face with a knife. On 14th December 1962, Edgecombe, fired a gun at Stephen Ward's Wimpole Mews flat, where Keeler had been visiting with Mandy Rice-Davies.

Two days after the shooting Christine Keeler contacted Michael Eddowes for legal advice about the Edgecombe case. During this meeting she told Eddowes "Stephen (Ward) asked me to ask Jack Profumo what date the Germans were to get the bomb." Eddowes then asked Ward about this matter. Keeler later recalled: "Stephen fed him the line he had prepared with Roger Hollis for such an eventuality: it was Eugene (Ivanov) who had asked me to find out about the bomb."

A few days later Keeler met John Lewis, a Labour Party MP and successful businessman at a Christmas party. Keeler later confessed: "I told him about Stephen asking me to get details about the bomb. I told him about Jack (Profumo). He told George Wigg, the powerful Labour MP with the ear of Harold Wilson. Wigg, who was Jack's opposite number in the Commons, started a Lewis-style dossier; it was the official start of the investigations and questions which would pull away the foundations of the Macmillan government."

A FBI document reveals that on 29th January, 1963, Thomas Corbally, an American businessman who was a close friend of Stephen Ward, told Alfred Wells, the secretary to David Bruce, the ambassador, that John Profumo was having a sexual relationship with Christine Keeler and Eugene Ivanov. The document also stated that Harold Macmillan had been informed about this scandal.

On 21st March, George Wigg asked Henry Brooke, the Home Secretary, in a debate on the John Vassall affair in the House of Commons, to deny rumours relating to Christine Keeler and the John Edgecombe case. Richard Crossman then commented that Paris Match magazine intended to publish a full account of Keeler's relationship with Profumo. Barbara Castle also asked questions if Keeler's disappearance had anything to do with Profumo.

The following day Profumo made a statement attacking the Labour Party MPs for making allegations about him under the protection of Parliamentary privilege, and after admitting that he knew Keeler he stated: "I have no connection with her disappearance. I have no idea where she is." He added that there was "no impropriety in their relationship" and that he would not hesitate to issue writs if anything to the contrary was written in the newspapers. As a result of this statement the newspapers decided not to print anything about Profumo and Keeler for fear of being sued for libel.

On 27th March, 1963, Henry Brooke summoned Roger Hollis, the head of MI5, and Joseph Simpson, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, to a meeting in his office. Philip Knightley pointed out in An Affair of State (1987): "All these people are now dead and the only account of what took place is a semi-official one leaked in 1982 by MI5. According to this account, when Brooke tackled Hollis on the rumour that MI5 had been sending anonymous letters to Mrs Profumo, Hollis vigorously denied it."

Roger Hollis then told Henry Brooke that Christine Keeler had been having a sexual relationship with John Profumo. At the same time Keeler was believed to be having an affair with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler, Stephen Ward had asked her "to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany." Hollis added that "in any court case that might be brought against Ward over the accusation all the witnesses would be completely unreliable" and therefore he rejected the idea of using the Official Secrets Act against Ward.

Henry Brooke then asked the Police Commissioner's view on this. Joseph Simpson agreed with Roger Hollis about the unreliable witnesses but added that it might be possible to get a conviction against Ward with a charge of living off immoral earnings. However, he added, that given the evidence available, a conviction was unlikely. Despite this response, Brooke urged Simpson to carry out a full investigation into Ward's activities.

On 25th May, 1963, George Wigg once again raised the issue of Keeler, saying this was not an attack on Profumo's private life but a matter of national security. On 5th June, John Profumo resigned as War Minister. His statement said that he had lied to the House of Commons about his relationship with Christine Keeler. The next day the Daily Mirror said: "What the hell is going on in this country? All power corrupts and the Tories have been in power for nearly twelve years."

Some newspapers called for Harold Macmillan to resign as prime minister. This he refused to do but he did ask Lord Denning to investigate the security aspects of the Profumo affair. Some of the prostitutes who worked for Stephen Ward began to sell their stories to the national press. Mandy Rice-Davies told the Daily Sketch that Christine Keeler had sexual relationships with Profumo and Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy.

After leaving politics Profumo worked for Toynbee Hall and in 1975 Profumo was awarded the CBE for his charity work for the disadvantaged in the East End of London.

In 1995 he told a friend: "Since 1963, there have been unceasing publications, both written and spoken, relating to what you refer to in your letter as the Keeler interlude. The majority of these have increasingly contained deeply distressing inaccuracies, so I have resolved to refrain from any sort of personal comment, and I propose to continue thus."

John Profumo died on 9th March, 2006.

Primary Sources

(1) John Profumo, statement in the House of Commons (22nd March, 1963)

I understand that my name has been connected with the rumours about the disappearance of Miss Keeler. I would like to take this opportunity of making a personal statement about these matters. I last saw Miss Keeler in December 1961 and I have not seen her since. I have no idea where she is now. Any suggestion that I was in any way connected with or responsible for her absence from the trial at the Old Bailey is wholly and completely untrue. My wife and I first met Miss Keeler at a house party in July 1961 at Cliveden. Among a number of people there was Dr Stephen Ward, whom we already knew slightly, and a Mr Ivanov, who was an attaché at the Russian Embassy. The only other occasion that my wife or I met Mr Ivanov was for a moment at the official reception for Major Gagarin at the Soviet Embassy. My wife and I had a standing invitation to visit DR Ward. Between July and December 1961, I met Miss Keeler on about half-a-dozen occasions at DR Ward's flat, when I called to see him and his friends. Miss Keeler and I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler. Mr Speaker, I have made this personal statement because of what was said in the House last evening by the three Honourable Members, and which of course was protected by privilege. I shall not hesitate to issue writs for libel and slander if scandalous allegations are made or repeated outside the House.

(2) John Profumo, letter to Harold Macmillan (5th June, 1963)

You will recall that on 22 March, following certain allegations made in Parliament, I made a personal statement. At the time rumour had charged me with assisting in the disappearance of a witness, and with being involved in some possible breach of security. So serious were these charges that I allowed myself to think that my personal association with that witness, which had also been the subject of rumour, was by comparison of minor importance only. In my statement I said that there had been no impropriety in this association. To my very deep regret I have to admit that this was not true, and that I misled you, and my colleagues, and the House.

I ask you to understand that I did this to protect, as I thought, my wife and family, who were equally misled, as were my professional advisers. I have come to realize that, by this deception, I have been guilty of a grave misdemeanour and despite the fact that there is no truth whatever in the other charges, I cannot remain a member of your Administration, nor of the House of Commons. I cannot tell you of my deep remorse for the embarrassment I have cause to you, to my colleagues in the Government, to my constituents, and to the Party which I have served for the past twenty-five years.

(3) Editorial in The Times (6th June, 1963)

There can be few more lamentable documents in British political history than Mr Profumo's letter of resignation. In his reply the Prime Minister says: "This is a great tragedy for you, your family, and your friends." It is also a great tragedy for the probity of public life in Britain.

(4) Report by Detective Sergeant John Burrows on his interview of Christine Keeler (January 1963)

She said that Doctor Ward was a procurer of young women for gentlemen in high places and was sexually perverted: that he had a country cottage at Cliveden to which some of these women were taken to meet important men - the cottage was on the estate of Lord Astor; that he had introduced her to Mr John Profumo and that she had an association with him; that Mr Profumo had written a number of letters to her on War Office notepaper and that she was still in possession of one of these letters which were being considered for publication in the Sunday Pictorial to whom she had sold her life story for £1,000. She also said that on one occasion when she was going to meet Mr Profumo, Ward had asked her to discover from him the date on which certain atomic secrets were to be handed over to West Germany by the Americans, and that this was at the time of the Cuban crisis. She also said she had been introduced by Ward to the Naval Attache of the Soviet Embassy and had met him on a number of occasions.

(5) John Profumo, statement (22nd March, 1963)

I understand that in the debate on the Consolidated Fund Bill last night, under the protection of parliamentary privilege, the Hon. Gentlemen the Members for Dudley (George Wigg) and for Coventry, East (Richard Crossman), and the Hon. Lady the Member for Blackburn (Barbara Castle), opposite, spoke of rumours connecting a Minister with a Miss Keeler and a recent trial at the Central Criminal Court. It was alleged that people in high places might have been responsible for concealing information concerning the disappearance of a witness and the perversion of justice.

I understand that my name has been connected with the rumours about the disappearance of Miss Keeler. I would like to take this opportunity of making a personal statement about these matters. I last saw Miss Keeler in December 1961, and I have not seen her since. I have no idea where she is now. Any suggestion that I was in any way connected with or responsible for her absence from the trial at the Old Bailey is wholly and completely untrue.

My wife and I first met Miss Keeler at a house party in July 1961, at Cliveden. Among a number of people there was Doctor Stephen Ward whom we already knew slightly, and a Mr Ivanov, who was an attache at the Russian Embassy.

The only other occasion that my wife or I met Mr Ivanov was for a moment at the official reception for Major Gagarin at the Soviet Embassy.

My wife and I had a standing invitation to visit Doctor Ward.

Between July and December, 1961, I met Miss Keeler on about half a dozen occasions at Doctor Ward's flat, when I called to see him and his friends. Miss Keeler and, I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler.

Mr Speaker, I have made this personal statement because of what was said in the House last evening by the three Hon. Members, and which, of course, was protected by privilege. I shall not hesitate to issue writs for libel and slander if scandalous allegations are made or repeated outside of the House.

(6) The Denning Report (1963)

After they got back to the flat Christine Keeler telephoned Mr. Michael Eddowes. (He was a retired solicitor who was a friend and patient of Stephen Ward and had seen a good deal of him at this time. He had befriended Christine Keeler and had taken her to see her mother once or twice.) Mr. Eddowes went round to see her. She told him of the shooting. He already knew from Stephen Ward something of her relations with Captain Ivanov and Mr. Profumo, and he asked her about them. He was most interested and subsequently noted it down in writing, and in March he reported it to the police. He followed it up by employing an ex-member of the Metropolitan Police to act as detective on his behalf to gather information.

(7) Time Magazine (1st May, 1989)

Britain's Minister of War John Profumo, husband of refined movie star Valerie Hobson, has been sharing the sexual favors of teen tart Christine Keeler with Soviet spy Eugene Ivanov . . . Keeler's blond pal Mandy Rice-Davies, 18, declared in court that she had bedded Lord Astor and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. . . . Mariella Novotny, who claims John F. Kennedy among her lovers, hosted an all-star orgy where a naked gent, thought to be film director and Prime Minister's son Anthony Asquith, implored guests to beat him . . . Osteopath and artist Stephen Ward, whose portrait subjects include eight members of the Royal Family, has been charged with pimping Keeler and Rice-Davies to his posh friends. Part of Ward's bail was reportedly posted by young financier Claus von Bulow.

(8) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Christine knew nothing of "cheque book journalism", but she had friends who did: Paul Mann, the racing driver/journalist and Nina Gadd, a freelance writer. Together they convinced her that, if she listened to them, she could make a small fortune. They reminded her that she was constantly broke and that Lucky Gordon was still making her life miserable. They told her they had been in touch with certain newspapers in Fleet Street which were prepared to offer her a great deal of money. This was true. Several newspapers were interested in Christine Keeler, especially when her appearance at the committal hearings of the Edgecombe shooting case at Marlborough Street Court reminded editors of the rumour floating around Fleet Street about her: that she was having an affair with Profumo.

There were problems, of course. The first was the English contempt law. No newspapers could publish anything about Christine's relationship with Edgecombe until his trial was over because the details of it were central to the charge. Next, there were the libel laws. If Christine's memoirs named other lovers, unless there was solid proof that what she said was true, they might sue for defamation. On the other hand most of the news at that time was bad, and a light sexy story of an English suburban girl who could arouse such passions - "I love the girl," Edgecombe had said, "I was sick in the stomach over her" - would certainly appeal to the readers of the Sunday sensational press.

Nina Gadd knew a reporter on the Sunday Pictorial, so on 22 January, with Mandy along to steady her resolve, Christine walked into the newspaper office carrying Profumo's farewell letter in her handbag. The newspaper's executives heard her out, looked at the letter, photographed it and offered her £1,000 for the right to publish it. Christine said she would think it over. She left the offices of the Sunday Pictorial and went straight to those of the News of the World, off Fleet Street. There she saw the paper's crime reporter, Peter Earle. Earle was desperate to have the story - for reasons that will emerge - but Christine made the mistake of telling him that his offer would have to be better than £1,000 because she had been offered that by another newspaper. Earle, who had had long experience of cheque book journalism, told Christine bluntly that she could go to the devil; he was not joining any auction.

So Christine went back to the Sunday Pictorial, accepted its offer and was paid £200 in advance. Over the next two days she told her entire life story to two Sunday Pictorial reporters. They soon saw that the nub of any newspaper article was her relationship with Profumo and Ivanov. It is easy to imagine how the story emerged. Christine was being paid £1,000 for her memoirs. The second slice, £800, was due only on publication. If the story did not reach the newspaper's expectations, Christine would not get it. She was anxious therefore to please the Sunday Pictorial reporters and dredged her memory for items that interested them. The trend of their questions would soon have indicated what items these were.

(9) Christine Keeler, The Truth at Last (2001)

Before the beginning of one of the greatest miscarriages of British justice ever, in early July 1963 I had to go to see Lord Denning at the government offices near Leicester Square. Denning had started hearing evidence on 24 June 1963, and interviewed Stephen three times and talked to Jack Profumo twice. He talked to lots of people - from the prime minister to newspaper owners and reporters, to six girls who knew Stephen.

I was not included in that half-dozen. I found myself a major player in the inquiry and had two interviews with Denning. I was allowed to have a legal representative and Walter Lyons went with me to the polished-wood-panelled offices Denning used. Denning was quietly spoken and asked me all the relevant questions, the ones I had expected. Questions like who had been present with Eugene and Stephen and where and when, and if I knew of any missiles. I answered him honestly. Denning had all the - well, all the ones they had given him - police, M15 and CIA reports before him. He also had Sir Godfrey Nicholson's and Lord Arran's statements.

He knew that Stephen was a spy and that I knew too much. During my two sessions with him I told him all about Hollis and Blunt: how Stephen had politely introduced me and how I had said "hello" and nodded when they visited. I told him all about Sir Godfrey's visit and how I had seen Sir Godfrey with Eugene. He asked me very precisely who had met Eugene and about the visitors to Wimpole Mews. He showed me a photograph of Hollis - it wasn't a sharp shot of him - and asked me to identify him. I told Denning this was the man who had visited Stephen. He showed me a photograph of Sir Godfrey and I also identified him. He did not show me a picture of Blunt for, I suspect, they already knew more than they wanted to know about Blunt. Denning was very gentle about it and I told him everything. This was the nice gentleman who was going to look after me. But I was ignored, side-lined - disparaged as a liar so that he could claim that there had been no security risk. It was the ultimate whitewash.

(10) The Times (10th March, 2006)

His subsequent wholly admirable charity work notwithstanding, John Profumo will be remembered as the the Secretary of State for War whose adulterous affair with the glamorous demi-mondaine Christine Keeler did more than anything to hasten the resignation of the Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in 1963. The scandal had an impact unique among sex and politics scandals in modern British life. Subsequent "minister and call-girl" stories — of which there were not a few — had nothing like its impact, nor were they treated with such seriousness.

There were many reasons for this. At the outset of the 1960s the more emancipated moral climate represented by the acquittal of Penguin Books over the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover still had to contend with the innate puritanism of the British people, which produced something of a backlash, especially on questions of sexual behaviour. Certainly, in an era when The Times could proclaim in the headline to a leading article on the matter: IT IS A MORAL ISSUE, the personal conduct of ministers was still held to count for something.

The story also had an alluring security element: the British War Minister was sharing Keeler’s sexual favours with those of a Russian naval attaché (ie spy), Captain Yevgeny Ivanov. And although the dangers of this were more imagined than real (Ivanov said later that Keeler would have been incapable of remembering the details of any military secrets imparted to her, even had pillow talk included them) it made for good headlines — and much righteous indignation from the parliamentary Opposition.

To add to all this, Profumo stoked the fires himself. His failure to come clean at the outset about the nature of his encounters with Keeler led to months of innuendo in the popular press which would simply not die down. Keeler’s life was of that colourful sort whose details were difficult to keep under wraps. She simply could not keep her mouth shut about anything she did. Jealous lovers fought over her in public, stabbing and wounding each other. One of them fired shots at her as she took refuge in the flat of another protector, the somewhat sinister and shadowy society osteopath, Stephen Ward, who became a key figure in the affair as a man later convicted of living off the earnings of prostitutes. When the case against her assailant came to trial Keeler, a key witness, had mysteriously disappeared abroad, and it was rumoured — quite wrongly as it happened — that Profumo had had a hand in this.

About his sexual relationship with Keeler Profumo consistently lied to parliamentary colleagues in private — which he might just have survived. But on March 22, 1963, he lied to Parliament — which he could not. While on holiday in Venice with his wife, the actress Valerie Hobson, in early June 1963, the burden of guilt suddenly became too much for him. He confessed to her; she persuaded him to return to London where he confessed to the Tory Chief Whip; he wrote a letter of resignation to the Prime Minister. It was immediately accepted. In the words of Lord Denning’s report on the affair: "Mr Profumo did not wait on the Queen to hand over the seals of office. They were sent by messenger. He applied for the Chiltern Hundreds and ceased to represent his constituency. The House of Commons held him to have been in contempt of the House. His name was removed from the Privy Council. His disgrace was complete."

It was the swiftest and most comprehensive eclipse of a public life imaginable. And in an age considerably before that in which the peccadilloes of such a man might well have the publishers queueing up with their chequebooks, it meant a long sojourn in obscurity. Profumo worked his way back, becoming a respected figure for his work among the poor and the down-and-outs of the East End. Whether this was any compensation for the loss of his political career was doubtful. But to his eternal credit, Profumo never offered any retrospective justification of himself. He accepted that "the Profumo case" would never go away in his lifetime, and that the periodic exhumation of its details was his lot in perpetuity.

(11) The Independent (10th March, 2006)

John Profumo, the man at the centre of the most notorious political sex scandal of the 20th century, has died at the age of 91 after suffering a stroke.

Profumo, who spent four decades atoning for his disgrace, died peacefully at about midnight last night surrounded by his family, a spokesman for London's Chelsea and Westminster Hospital said. He had been admitted to hospital two days earlier.

Today tributes were paid to the former Conservative Secretary of State for War, who was forced to resign from the Cabinet for lying to the House of Commons over his affair with call girl Christine Keeler.

His departure in 1963 signalled the downfall of Harold Macmillan's Conservative government, which lost the general election the following year.

Following his departure from politics, Profumo dedicated himself to charity work in the East End of London and was awarded the CBE in 1975.

He was shunned for many years by his former colleagues, some of whom blamed him for the Tories' decline in the 1960s.

(12) The Daily Telegraph (11th March, 2006)

Profumo was widely tipped as a future Foreign Secretary or Chancellor, but in 1961 there began the chain of events that would cost him his political career.

The Profumos had been invited by Lord Astor to spend a weekend on his estate at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire. Astor had let a cottage on the estate to Stephen Ward, a louche society osteopath whose client list included Winston Churchill, Sir Anthony Eden, Hugh Gaitskell and Frank Sinatra, but who also specialised in friendships with women of dubious virtue; one of Ward's guests that weekend was the 19-year-old Christine Keeler.

Profumo first set eyes on Christine Keeler when she stepped naked from Lord Astor's swimming pool, her costume having been snatched off her by Ward. Keeler left Cliveden that weekend with Yevgeny Ivanov, a Soviet attaché and friend of Ward, but Profumo asked Ward for Keeler's telephone number and afterwards began an affair that lasted several months.

MI5 apparently learned of the liaison from a tip-off by Ward, and Profumo subsequently ended the relationship after being warned that Ivanov was believed to be a spy. From then on Profumo sought to distance himself from the Cliveden set.

Over the next two years rumours about the affair began to circulate in Westminster, and on the evening of March 20 1963 the Labour MP Barbara Castle stood up in the House of Commons and asked directly whether the Secretary of State for War had been involved with Christine Keeler.

In the early hours of the following morning Profumo was summoned from his bed by the Government Chief Whip to a meeting with some of his ministerial colleagues at the House of Commons, at which he denied having had an affair with Keeler. In the House of Commons chamber the following day, with Macmillan sitting beside him, Profumo made a personal statement in which he declared that there had been "no impropriety whatsoever" in his relationship with Keeler.

For three months Profumo denied any impropriety; but his denials were challenged by Stephen Ward (then facing trial for living off immoral earnings), who wrote to Macmillan and the opposition leader, Harold Wilson, giving his version of events; it was also rumoured that Christine Keeler had made a series of taped confessions revealing their affair.

Eventually Profumo decided that he had no option but to come clean. After taking his wife to Venice to confess his infidelity, on June 5 1963 he resigned from the government and from Parliament. In his letter of resignation to Macmillan he expressed "deep remorse" at the embarrassment he had caused his colleagues and his constituents. A few days later he arrived at the door of Toynbee Hall and asked whether there was anything he could do to help.

(13) The New York Times (11th March, 2006)

Mr. Profumo was secretary of state for war in the government of Harold Macmillan in 1963 when rumors began to build of sexual romps among the nation's elite.

In March 1963, he went before Parliament to deny any "impropriety whatever" with Ms. Keeler. But just three months later, he was forced to resign as details of the relationship began to emerge and he admitted he had lied to Parliament.

Stephen Ward, an osteopath accused of running what the newspapers called a "top people's vice ring," was said to have introduced Mr. Profumo to Ms. Keeler in 1961 at a party at Lord Astor's country home in Berkshire. She was still in her teens; he was in his 40's. As the story went, he first caught sight of her climbing naked out of a swimming pool.

Some people thought the relationship might have remained secret, but it was much too explosive to stay hidden as rumors swirled.

Most dramatically, Ms. Keeler's other clients included Cmdr. Eugene Ivanov, the assistant naval attaché in the Soviet Embassy in London, whom she had also met through Mr. Ward. Government figures and MI5, the domestic intelligence agency, feared a grave security breach.

Ms. Keeler sold her story to newspapers but, at first, they refrained from publishing the details.

A third figure in the plot was Johnny Edgecombe, described as a petty criminal who was also sleeping with Ms. Keeler. When he became jealous and fired seven shots outside Mr. Ward's home, where she was staying, the story broke, opening a floodgate of reports about sexual misbehavior in high places involving Ms. Keeler and a colleague, Mandy Rice-Davies. Mr. Ward committed suicide in 1963 near the end of his trial on charges of living on immoral earnings, where he was found guilty.

The whole affair set off such an array of stories and rumors that the government had Lord Denning, a senior judge, conduct an inquiry. His report dismissed some of the juicier rumors — like one relating to a cabinet minister appearing at an orgy wearing only a maid's frilly apron and a mask.