Mandy Rice-Davies

Marilyn (Mandy) Rice-Davies was born in Mere, Wiltshire, on 21st October, 1944. Her father was a policeman before the war but later the family moved to Solihull where he took up a job at the Dunlop factory. Philip Knightley has pointed out: "Mandy, as she preferred to be called, was the daughter of a failed actress from Wales and a Welsh-born Birmingham policeman. She was a rebel at school, but enjoyed games and art, and sang in the choir in the local Anglican church. Her main interest was horses and she managed to buy and keep a pony of her own by doing a paper delivery round, helping in a racing stable and, later, working on Saturday mornings in a Birmingham dress shop."

Rice-Davies attended Sherman's Cross Secondary Modern School. She got a Saturday job at Marshall & Snelgrove and at the age of 15 she was working as a part-time model. She also started a relationship with a man, five years her senior. She remarked in her autobiography: "I was an enthusiastic participant in what struck me as a perfectly pleasant way to spend an afternoon."

In 1960, aged 16, Rice-Davies was employed as a model at the Earls Court Motor Show. After being paid £80 for the week's work, she decided to move permanently to London. She then got a job as a dancer at Murray's Cabaret Club in Soho where she met Christine Keeler. Rice-Davies claimed "it was dislike at first sight". However, they saw a lot of each other and eventually the two girls took part in "threesome" sex scenes with men. Rice-Davies later recalled: "She was an undemanding friend, happiest with people who made no demands on her. I enjoyed her company and learned never to rely on her for anything."

Christine Keeler introduced Rice-Davies to Stephen Ward and Lord Astor. The two men helped pay the rent for the two women to live in a flat at Comeragh Road. Soon afterwards, Rice-Davies met Keeler's old boyfriend, Peter Rachman. Rice-Davies became his mistress: "I was comfortable with him, he was easy to talk to, a good listener as well as a good talker." Anthony Summers points out in Honeytrap: "On and off, for nearly two years, he was to be her lover and the fount of all good things - and money seemed a very good thing to the sixteen-year-old from Solihull."

During this period Rice-Davies also met Maria Novotny, who ran sex parties in London. So many senior politicians attended that she began referring to herself as the "government's Chief Whip". As well as British politicians such as John Profumo and Ernest Marples, foreign leaders such as Willy Brandt and Ayub Khan, attended these parties.

On 21st January 1961, Colin Coote invited Stephen Ward to have lunch with Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy. The following month Ward and Christine Keeler moved to 17 Wimpole Mews in Marylebone. According to Keeler's autobiography, The Truth at Last (2001), Roger Hollis and Anthony Blunt were regular visitors to the flat.

On 8th July 1961 Christine Keeler met John Profumo, the Minister of War, at a party at Cliveden. Profumo kept in contact with Keeler and they eventually began an affair. At the same time Keeler was sleeping with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler: "Their (Ward and Hollis) plan was simple. I was to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany."

In December 1961 Mariella Novotny held a party that became known as the "Feast of Peacocks". According to Christine Keeler, there was "a lavish dinner in which this man wearing only... a black mask with slits for eyes and laces up the back... and a tiny apron - one like the waitresses wore in 1950s tearooms - asked to be whipped if people were not happy with his services."

In her autobiography, Mandy (1980) Rice-Davies described what happened when she arrived at Novotny's party in Bayswater: "The door was opened by Stephen (Ward) - naked except for his socks... All the men were naked, the women naked except for wisps of clothing like suspender belts and stockings. I recognised our host and hostess, Mariella Novotny and her husband Horace Dibbins, and unfortunately I recognised too a fair number of other faces as belonging to people so famous you could not fail to recognise them: a Harley Street gynaecologist, several politicians, including a Cabinet minister of the day, now dead, who, Stephen told us with great glee, had served dinner of roast peacock wearing nothing but a mask and a bow tie instead of a fig leaf."

Rice-Davies claims: "In early 1962 I received an offer to make a television commercial in the States. The producer had come to England to find a girl with a British accent, typically British-looking." At that time, Michael Lambton, one of Christine Keeler's boyfriends, was working in Philadelphia. Rice-Davies suggested that the two women should go to the United States together. Peter Rachman agreed to pay for trip.

On 11th July, 1962, Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler, arrived in New York City. They stayed at a hotel on Fire Island. According to Rice-Davies she fell asleep on the beach and was badly sunburnt. She telephoned the studio and told them: "I've had this accident - first-degree sunburn. It will take about a month if I am lucky to get my skin back in order." The women returned to London on 18th July. It later emerged that their movements in America were being monitored by the FBI.

On her return to London, Rice-Davies met Earl Felton, a screen-writer. Felton introduced her to Robert Mitchum and for a short time she worked as his personal assistant. According to Christine Keeler, Felton was a CIA agent.

After the death of Peter Rachman Rice-Davies became the mistress of Emil Savundra. Rice-Davies later commented: "Emil was larger than life. Well-born Ceylonese, with a brilliant mind he could have made his fortune in any number of legitimate businesses, but chose instead to give his life that added zest by looking for the dishonest twist in everything he did." Savundra paid her £25 a week for her services.

During this period Christine Keeler became involved with two black men, Lucky Gordon and John Edgecombe. The two men became jealous of each other and this resulted in Edgecombe slashing Gordon's face with a knife. On 14th December 1962, Edgecombe, fired a gun at Stephen Ward's Wimpole Mews flat, where Keeler had been visiting with Rice-Davies.

Keeler and Rice-Davies were interviewed by the police about the incident. According to Rice-Davies, as they left the police station, Keeler was approached by a reporter from the Daily Mirror. "He told her his paper knew 'the lot'. They were interested in buying the letters Profumo had written her. He offered her £2,000."

On 21st March, George Wigg asked the Home Secretary in a debate on the John Vassall affair in the House of Commons, to deny rumours relating to Christine Keeler and the John Edgecombe case. Richard Crossman then commented that Paris Match magazine intended to publish a full account of Keeler's relationship with John Profumo, the Minister of War, in the government. Barbara Castle also asked questions if Keeler's disappearance had anything to do with Profumo.

The following day Profumo made a statement attacking the Labour Party MPs for making allegations about him under the protection of Parliamentary privilege, and after admitting that he knew Keeler he stated: "I have no connection with her disappearance. I have no idea where she is." He added that there was "no impropriety in their relationship" and that he would not hesitate to issue writs if anything to the contrary was written in the newspapers.

On 23rd April 1963, Mandy Rice-Davies was arrested at Heathrow Airport on the way to Spain for a holiday, and formerly charged her with "possessing a document so closely resembling a driving licence as to be calculated to deceive." The magistrate fixed bail at £2,000. She later commented that "not only did I not have that much money, but the policeman in charge made it very clear to me that i would be wasting my energy trying to rustle it up." Rice-Davies spent the next nine days in Holloway Prison.

While she was in custody Rice-Davies was visited by Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert. His first words were: "Mandy, you don't like it in here very much, do you? Then you help us, and we'll help you." Herbert made it clear that Christine Keeler was helping them into their investigation into Stephen Ward. When she provided the information required she would be released from prison.

At first Rice-Davies refused to cooperate but as she later pointed out: "I was ready to kick the system any way I could. But ten days of being locked up alters the perspective. Anger was replaced by fear. I was ready to do anything to get out." Rice-Davies added: "Although I was certain nothing I could say about Stephen could damage him any way... I felt I was being coerced into something, being pointed in a predetermined direction." Herbert asked Rice-Davies for a list of men with whom she had sex or who had given her money during the time she knew Ward. This list included the names of Peter Rachman and Emil Savundra.

Mandy Rice-Davies appeared in court on 1st May 1963. She was found guilty and fined £42. Rice-Davies immediately took a plane to Majorca. A few days later Samuel Herbert telephoned her and said: "They would be sending out my ticket, they wanted me back in London, and if I didn't go voluntarily they would issue a warrant for extradition." Despite the fact that there was no extradition arrangement between the two countries, Rice-Davies decided to return to England.

On her arrival at Heathrow Airport she was arrested and charged with stealing a television set valued at £82. This was the set that Peter Rachman had hired for her flat. According to Rice-Davies: "I had signed the hire papers, and after he'd died I had never been allowed to remove the set." Chief Inspector Herbert arranged for Rice-Davies passport to be taken from her. She was released on the understanding that she would give evidence in court against Stephen Ward.

On 5th June, John Profumo resigned as War Minister. His statement said that he had lied to the House of Commons about his relationship with Christine Keeler. The next day the Daily Mirror said: "What the hell is going on in this country? All power corrupts and the Tories have been in power for nearly twelve years."

Some newspapers called for Harold Macmillan to resign as prime minister. This he refused to do but he did ask Lord Denning to investigate the security aspects of the Profumo affair. Some of the prostitutes who worked for Stephen Ward began to sell their stories to the national press. Mandy Rice-Davies told the Daily Sketch that Christine Keeler had sexual relationships with John Profumo and Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy.

On 7th June, Keeler told the Daily Express of her secret "dates" with Profumo. She also admitted that she had been seeing Eugene Ivanov at the same time, sometimes on the same day, as Profumo. In a television interview Stephen Ward told Desmond Wilcox that he had warned the security services about Keeler's relationship with Profumo.

The following day Ward was arrested and charged with living off immoral earnings between 1961 and 1963. He was refused bail because it was feared that he might try to influence witnesses. Another concern was that he might provide information on the case to the media.

On 14th June, the London solicitor, Michael Eddowes, claimed that Christine Keeler told him that Eugene Ivanov had asked her to get information about nuclear weapons from Profumo. Eddowes added that he had written to Harold Macmillan to ask why no action had been taken on information he had given to Special Branch about this on 29th March. Soon afterwards Keeler told the News of the World that "I'm no spy, I just couldn't ask Jack for secrets."

The trial of Stephen Ward began at the Old Bailey on July 1963. Christine Keeler and Rice-Davies, were both called as witnesses. Mandy Rice-Davies admitted receiving money and gifts from Peter Rachman and Emil Savundra. As she was living with Ward at the time she gave him some of this money for unpaid rent. As Rice-Davies pointed out: "Much was made of the fact that I was paying him a few pounds a week whilst I was living in Wimpole Mews. But I said before and say it again - Stephen never did anything for nothing and we agreed on the rent the day I arrived. He most certainly never influenced me to sleep with anyone, nor ever asked me to do so." She added: "Stephen was never a blue-and-white diamond, but a pimp? Ridiculous.... As for Christine, she was always borrowing money (from Stephen Ward)."

Ronna Ricardo had said that she had sex for money and then gave it to Ward at a preliminary hearing. However, she retracted this information at the trial and claimed that Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert had forced the statement from her by threats against the Ricardo family. According to Philip Knightley: "Ricardo said that Herbert told her that if she did not agree to help them then the police would take action against her family. Her younger sister, on probation and living with her, would be taken into care. They might even make application to take her baby away from her because she had been an unfit mother."

The main evidence against Stephen Ward came from Vickie Barrett. She claimed that Ward had picked her up in Oxford Street and had taken her home to have sex with his friends. Barrett was unable to name any of these men. She added that Ward was paid by these friends and he kept some of the money for her in a little drawer. Christine Keeler claims that she had never seen Barrett before: "She (Barrett) described Stephen handing out horsewhips, canes, contraceptives and coffee and how, having collected her weapons, she had treated the waiting clients. It sounded, and was, nonsense. I had lived with Stephen and never seen any evidence of anything like that... She has never to my knowledge been seen again. I suspect she was spirited out of the country, given a new identity, a new life."

Ward told his defence counsel, James Burge: "One of my great perils is that at least half a dozen of the (witnesses) are lying and their motives vary from malice to cupidity and fear... In the case of both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies there is absolutely no doubt that they are committed to stories which are already sold or could be sold to newspapers and that my conviction would free these newspapers to print stories which they would otherwise be quite unable to print (for libel reasons)."

Stephen Ward was very upset by the judge's summing-up that included the following: "If Stephen Ward was telling the truth in the witness box, there are in this city many witnesses of high estate and low who could have come and testified in support of his evidence." Several people present in the court claimed that Judge Archie Pellow Marshall was clearly biased against Ward. France Soir reported: "However impartial he tried to appear, Judge Marshall was betrayed by his voice."

That night Ward wrote to his friend, Noel Howard-Jones: "It is really more than I can stand - the horror, day after day at the court and in the streets. It is not only fear, it is a wish not to let them get me. I would rather get myself. I do hope I have not let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff but after Marshall's summing-up, I've given up all hope." Ward then took an overdose of sleeping tablets. He was in a coma when the jury reached their verdict of guilty of the charge of living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies on Wednesday 31st July. Three days later, Ward died in St Stephen's Hospital.

In his book, The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964), Ludovic Kennedy considers the guilty verdict of Ward to be a miscarriage of justice. In An Affair of State (1987), the journalist, Philip Knightley argues: "Witnesses were pressured by the police into giving false evidence. Those who had anything favourable to say were silenced. And when it looked as though Ward might still survive, the Lord Chief Justice shocked the legal profession with an unprecedented intervention to ensure Ward would be found guilty."

At the end of the Ward trial, Newspapers began reporting on the sex parties attended by Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler. The Washington Star quoted Rice-Davies as saying "there was a dinner party where a naked man wearing a mask waited on table like a slave." Dorothy Kilgallen wrote an article where she stated: "The authorities searching the apartment of one of the principals in the case came upon a photograph showing a key figure disporting with a bevy of ladies. All were nude except for the gentleman in the picture who was wearing an apron. And this is a man who has been on extremely friendly terms with the very proper Queen and members of her immediate family!"

The News of the World immediately identified the hostess at the dinner party as being Mariella Novotny. Various rumours began to circulate about the name of the man who wore the mask and apron. This included John Profumo and another member of the government, Ernest Marples. Whereas another minister, Lord Hailsham, the leader of the House of Lords at the time, issued a statement saying it was not him. Novotny refused to comment on her activities and the man in the mask remained unidentified. However, Time Magazine speculated that it was film director, Anthony Asquith, the son of former prime minister, Herbert Asquith.

Rice-Davies purchased a mews house in Cornwall Mews West with the money she made from newspaper articles. She tried to make a living as an actress and appeared in two films in 1963, Hide and Seek (not credited) and the Keeler Affair. She also published a book, The Mandy Report, that challenged the conclusions of The Denning Report. However, the publishers disappeared and she claims that she received no money for her book.

In 1964 she was asked to play a lead role in the film Fanny Hill, based on the book written by John Cleland. However, the film was never made. Her next offer was as a singer at Eve's Bar in Munich. She was paid £150 a night. The Times reported: "She came onstage trembling, spoke in a whisper, and apologized that in her nineteen years she had never used a microphone or appeared before a crowd." Rice-Davies followed this with a contract to sing at Cordon Blue for nearly £2,000 a week. She was eventually deported from Turkey for singing Cole Porter's Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love.

On her return to England she began a tour of Working Men's Clubs. As she pointed out in her autobiography: "One-night stands were particularly well paid. A night here and a night there meant £250 a time." On one occasion she had laryngitis and she was replaced by Tom Jones at the Top Hat in in Cwmtillery. That night Jones was spotted by Gordon Mills, who signed him up and took the young singer to London.

Rice-Davies also toured Spain, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore but was banned from entering New Zealand as a result of a complaint from the Girl Guides. She was booked for The Sands Hotel in Las Vegas but the authorities refused to grant her a visa. This resulted in her being banned from appearing at El Patio in Mexico City.

While touring Israel Rice-Davies met Rafael Shaul, who owned the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Tel Aviv. The couple were married on 17th September 1966. Soon afterwards they established Mandy's Club. it was a great success: "Mandy's was a membership club: 500 official members and a waiting list which reached several thousands... The club was the first of several. Our brand of expertise became extremely marketable." Rice-Davies also joined forces with Monty Marks, a London-based fashion manufacturer, to open a dress factory aimed at the younger market. She later commented: "By the time I left Israel, it was a very big factory with a huge turnover."

Many Rice-Davies parted from her husband in 1971 but they continued to be business partners. She also continued her acting career in Israel and appeared in several films including Kuni Leml B'Tel Aviv (1976), Hershele (1977) and Millioner Betzarot (1978).

In 1980 Mandy Rice-Davies published her autobiography, Mandy. She continued to work as an actress and appeared in Nana (1982), The Seven Magnificent Gladiators (1983), Kuni Leml B'Kahir (1983), Black Venus (1983) and Absolute Beginners (1986).

I was contacted by Mandy Rice-Davies in March, 2009. She objected to a quotation from Christine Keeler that I had included on my website. She also gave me some more information on the case: "Regina v Ward was undoubtedly one of the most vindictively rigged trials of the 20th Century. The Macmillan government, plagued throughout their office by spy cases, were eager to shift the security aspects of the Profumo business out of the spotlight. Aristocratic by nature and clinging to the old values of a swiftly vanishing past, they cast about for lessor, more expendable mortals on who to pin the blame. The establishment aimed their arrows at Stephen Ward and a couple of teenage girls who were doing nothing more than chasing a good time. The police with Machiavellian cunning threw in a couple of known prostitutes to muddy the waters. Three days after Profumo confessed and resigned, Stephen Ward was arrested and a case that barely had legs to stand on was dragged kicking and screaming into court. Ward may have been a man with lax moral standards and uncertain principles, but other than a few muddled insinuations from the priggish prosecution no evidence was produced to show that Stephen Ward was a pimp. There is no doubt that had Ward not committed suicide, the case would have been dismissed on appeal. In regard to myself, the worst I could be accused of is bad judgment and a healthy libido. I was only eighteen years old when the storm broke and after getting on with the rest of my life 1963 still casts a shadow."

One of the most disturbing things that Mandy Rice-Davies told me was that she was convinced that Ward's defence team was in some way involved in the conspiracy. She was told that in court she was asked questions that would enable her to clear Ward of living on her immoral earnings. However, when she testified, she was never asked questions on this matter and therefore was denied the opportunity of saying that the only money she ever gave him was the rent for the flat. In fact, it was Ward who was giving her money.

Mandy Rice-Davies died of cancer on 18th December, 2014.

Primary Sources

(1) Christine Keeler, The Truth at Last (2001)

I thought Mandy Rice-Davies was a true tart. There was always shock on her face whenever she thought she might have to do more than lie on her back to make a living. Or swing from chandeliers. In the years since we first met I feel she has misrepresented events and put me down. She must have liked my style though - for she impersonated it in her fantasies, taking over my life.

Mandy handed out quotes as readily as her sexual services. I hope the sex was better value. However unwittingly, she contributed through her silly stories to the official cover-up of the political upheaval of the early Sixties. Yes she was young and heedless but, still, she caused serious trouble to me and others by her antics.

She had just turned sixteen when I first met her in September 1960. She had lost her virginity and any illusions a year earlier. Her heavy make-up added a few years but she was bubbly. There was that fun about her - she was the other side of the coin from Sherry who was no free spirit.

Policeman's daughter Marilyn Rice-Davies from Solihull, Birmingham, was, as Mandy Rice-Davies, up for anything. Sex or larks and a laugh. She called herself a model but that was more in hope than in her c.v. Everything about her said `I Want to Marry a Millionaire'; she might as well have carried a placard.

(2) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Mandy, as she preferred to be called, was the daughter of a failed actress from Wales and a Welsh-born Birmingham policeman. She was a rebel at school, but enjoyed games and art, and sang in the choir in the local Anglican church. Her main interest was horses and she managed to buy and keep a pony of her own by doing a paper delivery round, helping in a racing stable and, later, working on Saturday mornings in a Birmingham dress shop.

She left school at 15, found a job in a department store, and bullied her way into helping organise the store's fashion show, which was arranged to coincide with the local preview of a British film Make Mine Mink. Her hair backcombed and lacquered into a towering bouffant extravaganza, Mandy posed with the stars of the film, Terry Thomas and Hattie Jacques, for the Birmingham Post photographer. Then the company limousine drove her home. This was heady stuff for a Birmingham teenager and soon afterwards when a man stopped her in the street and offered her a job modelling at the Earls Court motor show, she accepted with alacrity.

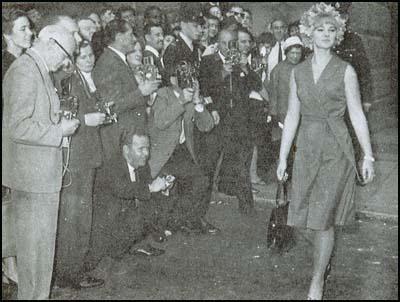

The Mini was the most photographed car that year and many of the photographs show a cheeky, open-faced young girl with bobbed hair, thick black eyebrows, a turned-up nose and an appealing smile. Mandy was also photographed at receptions, cocktail parties, dinners, and on the way to lunch with the Mini's brilliant designer, Alex Issigonis. She returned to Birmingham with £80 in her purse and her mind made up: she was going to live in London. When her parents objected, she packed her luggage in secret, waited until they were out, and left for the station.

Two hours later Mandy opened the pages of the London Evening Standard and ran her finger down the `situations vacant' column. One advertisement seemed to stand out: "Murray's Club requires dancers." She auditioned that same afternoon, forged a letter of consent from her parents, and started work the next night.

Mandy was at Murray's for several weeks before she met Christine. The dancers were considered a professional cut above the showgirls and had separate dressing rooms so it was possible for two girls to work at Murray's and seldom meet. In the end another girl formally introduced them. It was not a happy meeting. Christine made a few uncomplimentary remarks about Mandy's excessive use of green eye shadow...

The two girls quickly became firm friends. Christine often stayed the night at Mandy's flat. She enjoyed cooking late breakfasts and amusing Mandy with stories about her love affairs. Mandy, for her part, made fruitless efforts to sort out Christine's finances. It is difficult at this distance to decide who was the leading character. Mandy implies that Christine's life was chaotic and she needed Mandy to organise it. Christine says that Mandy was an over-confident 16-year-old and that she took her in hand and was always the boss.

(3) Mandy Rice-Davies, The Mandy Report (1964)

In early 1962 I received an offer to make a television commercial in the States. The producer had come to England to find a girl with a British accent, typically British-looking. He was very impressed with me and the fact that I looked very much like Vivien Leigh, oddly enough. I was blonde but they planned to do me with dark hair. They did test shots of me and after make up you could not tell who was me and who was Vivien Leigh. It is not apparent in the flesh, but very striking in photographs, for we have similar bone structure and mouth; and, photographed from a certain angle, the bump in my nose is disguised.

(3) Mandy Rice-Davies, The Mandy Report (1964)

Rachman was dead but I had not heard the last of his name. Attempting to leave London Airport on April 23 (1963) I was arrested whilst passing through Passport Control and taken by police car back to town. Then I was charged with driving under a forged licence, whilst uninsured, and making false statements to obtain insurance. This was all to do with the Jaguar and the phoney licence that Peter had provided for my birthday.

That night I slept on a hard straw mattress in a prison cell at Holloway. The next morning I appeared in a magistrate's court where police opposed bail on the grounds that I might try to leave the country. It was a fantastic situation and quite impossible to understand. You would have thought I had stolen the Crown jewels or something like-or stopped a mail train in Buckinghamshire. My solicitor objected to the police statement and finally bail was set at £2,000. But when friends came up with the money the real significance of the case came to light.

A detective told me: "You'd be well advised not to accept bail. As soon as you're released we're going to arrest you on another charge. In fact we've got two warrants for your arrest. One of them is a bench warrant for parking in a wrong street and not turning up at court. If we re-arrest you, it'll mean finding another £2,000 bail. Take my advice and stay inside for another week. It'll cause you less trouble in the long run".

On two previous occasions the police had been to see me about making a statement on my relations with Stephen Ward. Each time I had refused. Clearly these proceedings were related to my refusal to co-operate and this was why I had to be kept behind bars. Well, back to jail I went. Holloway Prison must be one of the last places that God ever made on this earth. The conditions I thought were absolutely vile. ' I was turned out of my bunk every morning at 6 a.m. and locked up for bed again at g p.m. Compared with what I had been accustomed to, the food was like pigswill and tasted every bit as vile as it looked...

After a day or two of this I was ready to do anything to get out. I am sure that this was the way the police had planned it. They came to see me and asked if I would like to reconsider my refusal to make a statement about Dr Ward. The prospect of perhaps having to spend a further spell in Holloway over the motoring offence was enough to convince me that I had better keep on the right side of the police. I felt like a cornered animal. I told them all they wanted to know . . . and slowly the noose began tightening round Stephen's neck.

When my case went into court I was let off with a £42 fine and a warning. I left at once for Majorca....

At the airport (on her return from Majorca) I was met by two detectives from the Yard.

"Oh no", I said. "Not again". They wanted to grill me further about Stephen's life but I told them that everything I had to say had been said when I was in Holloway. Their faces looked ' a little strained at this news and I had the feeling that we would meet again...

A few days later I was again called in by the police and interviewed for four-and-a-half hours, going all over the same ground again. I was getting pretty sick of this and decided that Majorca was the place to be. Things were moving very quickly.

On June 4, Jack Profumo resigned as War Minister and as an M.P. Three days later, Stephen Ward was arrested and charged with living on immoral earnings. And on the 16th, again on my way to Majorca, I was stopped and arrested for the second time whilst passing through London Airport. Again .the police were about to pull a fast one on me.

I was driven to Marylebone police station and charged with the larceny of a TV set. The police asked me to enter in recognisances of £1,000. The condition of this was that I was to appear at Marylebone Court. By "coincidence" it turned out that I was to appear on the same day as the start of the hearing against Ward! (The television set I was supposed to have stolen was removed from Peter's flat at Bryanston Mews after his death. They claimed that I had taken it. This was completely and utterly untrue and, in fact, nothing ever came of this charge. But it had enabled the police to take away my passport until after the Ward hearing.)

The preliminary hearing of Stephen's case opened on June 28. Frankly, I thought the whole business was a farce. No one would deny that Stephen was a depraved and immoral man. But to suggest that he made a living out of it is nonsense.

Much was made of the fact that I was paying him a few pounds a week whilst I was living in Wimpole Mews. But I said before and say it again - Stephen never did anything for nothing and we agreed on the rent the day I arrived. He most certainly never influenced me to sleep with anyone, nor ever asked me to do so.

(4) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

The door was opened by Stephen (Ward) - naked except for his socks... All the men were naked, the women naked except for wisps of clothing like suspender belts and stockings. I recognised our host and hostess, Mariella Novotny and her husband Horace Dibbins, and unfortunately I recognised too a fair number of other faces as belonging to people so famous you could not fail to recognise them: a Harley Street gynaecologist, several politicians, including a Cabinet minister of the day, now dead, who, Stephen told us with great glee, had served dinner of roast peacock wearing nothing but a mask and a bow tie instead of a fig leaf.

(5) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

"It was dislike at first sight," Rice-Davies recalls, and "Keeler felt the same. Nevertheless, partly because Rice-Davies got on well with Arabs, and they both ended up at the same parties, the two became companions. They functioned well together in company - partly, Keeler thought, I because Rice-Davies had a good head for money, while she II was vague about it.

The partnership also worked well in the bedroom. Though there were no lesbian overtones, the two girls took , part in "threesome" sex scenes with men. Keeler says this became something of a speciality, that it excited the men so much that they forgot any desire they might have had for a two-woman show. She says neither of the girls was a bit bothered by group sex - it was amusing, and it brought in money for clothes and partying. Rice-Davies confirms that the threesomes took place.

Unlike Christine Keeler, who looked better in photographs than in life, Rice-Davies was to survive the 1963 scandal still looking "fresh as a milkmaid". She had "a hard cat-like face," said one observer, "but a very pretty one."

In her two months at Murray's, Rice-Davies found many wealthy admirers but - at that stage - not much sex. She started with Azis, a friend of Keeler's Ahmed, and then discovered Walter Flack, a partner of property magnate Charles Clore. Clore was to have sex with Keeler for money. Flack, on the other hand, wined and dined Rice-Davies but never propositioned her.

Eric, Earl of Dudley, seemed a good bet. He showered Rice-Davies with flowers, sent a case of pink champagne and took her out in his ancient Jaguar. He told Rice-Davies how to address the Queen should they meet, and actually took her to dinner with the woman who missed being Queen, the Duchess of Windsor. Lord Dudley at one point proposed to Rice-Davies, but then he quarrelled with her over Aziz and went off to marry Princess Grace Radziwill.

(6) FBI document (July, 1963)

Reference is made to my letter of June 24, 1963, which you returned to the Assistant Director C. A. Evans on July 2, 1963. At the time you inquired if we had learned what Christine (Keeler) and her friend did in the U.S. when they were here...

It has been learned that Christine Keeler and Marilyn Rice-Davies arrived in the U.S. aboard the SS Niew Amsterdam on July 11, 1962. They registered at the Hotel Bedford, 118 East 42nd Street, New York City, July 11, 1962, and re-registered on July 16, 1962. Hotel records do not show a date of departure; however, they did leave the U.S. on July 18, 1962, by British Overseas Airways Corporation plane.

(7) Time Magazine (1st May, 1989)

Britain's Minister of War John Profumo, husband of refined movie star Valerie Hobson, has been sharing the sexual favors of teen tart Christine Keeler with Soviet spy Eugene Ivanov . . . Keeler's blond pal Mandy Rice-Davies, 18, declared in court that she had bedded Lord Astor and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. . . . Mariella Novotny, who claims John F. Kennedy among her lovers, hosted an all-star orgy where a naked gent, thought to be film director and Prime Minister's son Anthony Asquith, implored guests to beat him . . . Osteopath and artist Stephen Ward, whose portrait subjects include eight members of the Royal Family, has been charged with pimping Keeler and Rice-Davies to his posh friends. Part of Ward's bail was reportedly posted by young financier Claus von Bulow.

(8) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Christine knew nothing of "cheque book journalism", but she had friends who did: Paul Mann, the racing driver/journalist and Nina Gadd, a freelance writer. Together they convinced her that, if she listened to them, she could make a small fortune. They reminded her that she was constantly broke and that Lucky Gordon was still making her life miserable. They told her they had been in touch with certain newspapers in Fleet Street which were prepared to offer her a great deal of money. This was true. Several newspapers were interested in Christine Keeler, especially when her appearance at the committal hearings of the Edgecombe shooting case at Marlborough Street Court reminded editors of the rumour floating around Fleet Street about her: that she was having an affair with Profumo.

There were problems, of course. The first was the English contempt law. No newspapers could publish anything about Christine's relationship with Edgecombe until his trial was over because the details of it were central to the charge. Next, there were the libel laws. If Christine's memoirs named other lovers, unless there was solid proof that what she said was true, they might sue for defamation. On the other hand most of the news at that time was bad, and a light sexy story of an English suburban girl who could arouse such passions - "I love the girl," Edgecombe had said, "I was sick in the stomach over her" - would certainly appeal to the readers of the Sunday sensational press.

Nina Gadd knew a reporter on the Sunday Pictorial, so on 22 January, with Mandy along to steady her resolve, Christine walked into the newspaper office carrying Profumo's farewell letter in her handbag. The newspaper's executives heard her out, looked at the letter, photographed it and offered her £1,000 for the right to publish it. Christine said she would think it over. She left the offices of the Sunday Pictorial and went straight to those of the News of the World, off Fleet Street. There she saw the paper's crime reporter, Peter Earle. Earle was desperate to have the story - for reasons that will emerge - but Christine made the mistake of telling him that his offer would have to be better than £1,000 because she had been offered that by another newspaper. Earle, who had had long experience of cheque book journalism, told Christine bluntly that she could go to the devil; he was not joining any auction.

So Christine went back to the Sunday Pictorial, accepted its offer and was paid £200 in advance. Over the next two days she told her entire life story to two Sunday Pictorial reporters. They soon saw that the nub of any newspaper article was her relationship with Profumo and Ivanov. It is easy to imagine how the story emerged. Christine was being paid £1,000 for her memoirs. The second slice, £800, was due only on publication. If the story did not reach the newspaper's expectations, Christine would not get it. She was anxious therefore to please the Sunday Pictorial reporters and dredged her memory for items that interested them. The trend of their questions would soon have indicated what items these were.

(9) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

The trial lasted over a week. On Tuesday of the second week, 30th July, the judge began his summing up. We knew there was no hope. Much was made of the fact that in his hour of need none of Stephen's good friends came forward as a character witness. They didn't because Stephen asked them not to. He was embarrassed at involving them needlessly, he believed. When the investigations began he couldn't believe they would lead anywhere, and he insisted his friends stay out of it. Bill Astor certainly volunteered, and probably others did, too. By the time he knew he needed help, the fat was in the fire. My father always said he regretted not coming forward. That would have made news - father appearing for the defence, his daughter for the prosecution.

That evening Stephen went back to the flat in Chelsea where he was a guest during the trial. He wrote several letters - including one to Vickie Barrett - to be delivered "only if I am convicted and sent to prison". He cooked a meal for himself and his girlfriend, Julie Gulliver, then drove her home. He drove around for a while, possibly thinking things over, then, his mind made up, went back to the flat. He wrote another letter, to his friend and host Noel Howard Jones, and swallowed an overdose of nembutal.

(10) Mandy Rice-Davies, statement sent to John Simkin (23rd March, 2009)

Regina v Ward was undoubtedly one of the most vindictively rigged trials of the 20th Century. The Macmillan government, plagued throughout their office by spy cases, were eager to shift the security aspects of the Profumo business out of the spotlight. Aristocratic by nature and clinging to the old values of a swiftly vanishing past, they cast about for lessor, more expendable mortals on who to pin the blame.

The establishment aimed their arrows at Stephen Ward and a couple of teenage girls who were doing nothing more than chasing a good time. The police with Machiavellian cunning threw in a couple of known prostitutes to muddy the waters.

Three days after Profumo confessed and resigned, Stephen Ward was arrested and a case that barely had legs to stand on was dragged kicking and screaming into court.

Ward may have been a man with lax moral standards and uncertain principles, but other than a few muddled insinuations from the priggish prosecution no evidence was produced to show that Stephen Ward was a pimp. There is no doubt that had Ward not committed suicide, the case would have been dismissed on appeal.

In regard to myself, the worst I could be accused of is bad judgment and a healthy libido. I was only eighteen years old when the storm broke and after getting on with the rest of my life 1963 still casts a shadow. However a scandal is a scandal whatever the outcome and there will always be those who for personal gain or simple spite will try to distort the truth.