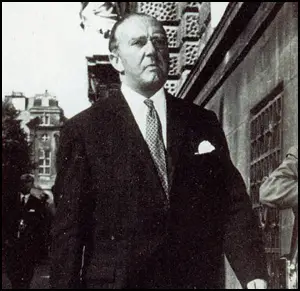

James Burge

Charles George James Burge was born on 8th October 1906. He was educated at Christs College and after leaving the University of Cambridge, he became a barrister and was employed at the Queen Elizabeth Building, Temple, London.

Ludovic Kennedy described him "as a jovial, sunshiney, Pickwickian sort of man, who always seems to be smiling." Kennedy added: "It was not entirely coincidence, I thought, that some of his practice was devoted to licensing cases. Beer and Burgundy seemed to blend with his beaming face." Anthony Summers and Stephen Dorril, the authors of Honeytrap (1987) have pointed out: "Burge, it has been said, was a model for the character of John Mortimer's Rumpole, and Mortimer does not deny it."

In the 1950s Burge became a patient of Dr. Stephan Ward. In April, 1963, Ward was accused of living off the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies. Ward asked Burge to represent him when he appeared at the the Magistrate's Court. Although he was not a Q.C., Ward decided to retain him for the trial. The trial of Stephen Ward began at the Old Bailey on 22nd July 1963. Christine Keeler admitted in court that she had sex with John Profumo, Charles Clore and Jim Eynan. In all three cases the men gave her money and gifts. During cross-examination she confessed that some of this money was paid to Ward as she owed him money for rent, electricity and food while she was living at his flat.

Mandy Rice-Davies also admitted receiving money and gifts from Peter Rachman and Emil Savundra. As she was living with Ward at the time she gave him some of this money for unpaid rent. As Rice-Davies pointed out: "Much was made of the fact that I was paying him a few pounds a week whilst I was living in Wimpole Mews. But I said before and say it again - Stephen never did anything for nothing and we agreed on the rent the day I arrived. He most certainly never influenced me to sleep with anyone, nor ever asked me to do so." She added: "Stephen was never a blue-and-white diamond, but a pimp? Ridiculous.... As for Christine, she was always borrowing money (from Stephen Ward)."

Ludovic Kennedy, the author of The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964) has argued that Burge was unable to compete with the prosecuting counsel Mervyn Griffith-Jones: "In short, Mr. Burge was a very nice man; indeed, as the trial went on, I began to think that alongside Mr. Griffith-Jones, he was almost too nice a man. He was a civilised being, a person of wit and humour. I had been told by one of his colleagues that he was one of the few men at the Bar who could laugh a case out of court. The atmosphere here, as I think he realised, was not conducive to this sort of approach, but I was told he had tried it once or twice at the Magistrate's Court with some success. In addition to his quip about Mr. Griffith-Jones making a honeymoon sound obscene, he had also said that he had no objection to some of Mr Griffith-Jones's leading questions, as they were not leading very far. Mr. Griffith-Jones himself would have been incapable of either of these two remarks. But equally Mr. Burge could not match Mr. Griffith-Jones's cold relentless plodding, his battering away at the walls until, by sheer persistence, they began to crack. It was this, in the last analysis, that made one admire Mr. Griffith-Jones as much as one deplored him. Because his own attitude to the case was committed, one became committed in one's attitude towards him. It was this outward lack of commitment, not in matter but in manner, that at times led one to feel that Mr. Burge was doing himself literally less than justice. They say that the days of the committed lawyer are over: yet one would have liked to see Ward's defence accompanied by some passion, with his counsel as contemptuous of the charges laid against him as the prosecution were contemptuous of Ward himself. As it was, while I had no doubts which of the two counsel was the more intelligent, urbane and congenial, equally I had no doubts, where the jury was concerned, which was the more effective advocate."

In his cross-examination of Stephan Ward, Burge asked him about his annual income. Ward replied that he was earning about £4,000 from his practice and another £1,500 or so from his drawings - a total of between £5,000 and £6,000 a year. Burge then asked: "If the prosecution's picture of a man procuring, and the picture of people in high places and very wealthy men was true, would you have needed to carry on your practice and work as an osteopath?" Ward replied: "If that were true, evidently not."

Philip Knightley, the author of An Affair of State (1987) pointed out: "That ended the prosecution case. How strong was it? Griffith-Jones had succeeded in establishing that Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies took money for sex. He had shown that both girls gave money to Ward. Even though, given that in law the dividing line between living with a prostitute and living on a prostitute is very thin, the prosecution's weak point was that both girls owed Ward - one way or another - far more money than they ever paid him."

At the end of the case, Stephan Ward told Burge: "One of my great perils is that at least half a dozen of the (witnesses) are lying and their motives vary from malice to cupidity and fear... In the case of both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies there is absolutely no doubt that they are committed to stories which are already sold or could be sold to newspapers and that my conviction would free these newspapers to print stories which they would otherwise be quite unable to print (for libel reasons)."

Stephen Ward was very upset by the judge's summing-up that included the following: "If Stephen Ward was telling the truth in the witness box, there are in this city many witnesses of high estate and low who could have come and testified in support of his evidence." Several people present in the court claimed that Judge Archie Pellow Marshall was clearly biased against Ward. France Soir reported: "However impartial he tried to appear, Judge Marshall was betrayed by his voice."

After the day's court proceedings, Ward contacted Tom Critchley, a Home Office official working with Lord Denning on the official investigation. Later, Critchley refused to comment what was said in that telephone conversation. That night Ward met the journalist Tom Mangold: "Stephen was very relaxed... He wasn't walking around in a froth. He was very calm and collected, just writing his letters and putting them in envelopes. I wanted to pretend that I hadn't seen what I'd seen. My excuse, which was not a good excuse, was that I was on a yellow card from my wife. I reckoned I could risk being home two hours late. But I knew the marriage wouldn't survive if I showed up any later. So all I did was to bleat at Stephen not to do anything foolish."

After Mangold left Stephan Ward wrote to his friend, Noel Howard-Jones: "It is really more than I can stand - the horror, day after day at the court and in the streets. It is not only fear, it is a wish not to let them get me. I would rather get myself. I do hope I have not let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff but after Marshall's summing-up, I've given up all hope." Ward then took an overdose of sleeping tablets. He was in a coma when the jury reached their verdict of guilty of the charge of living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies on Wednesday 31st July. Three days later, Ward died in St Stephen's Hospital.

Burge's friend, Sir David Napley later commented: "When Ward committed suicide, Jimmy Burge was very affected. He never seemed to be the same man again... It was not long after this that he left the bar and took up residence abroad."

James Burge died on 6th September 1990.

Primary Sources

(1) Ludovic Kennedy, The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964)

It was now the turn of Ward's defence counsel, Mr. James Burge. Mr. James Burge was not a Q.C., as might have been expected in a case of this importance, and I understood that that was because Ward had been so pleased with his handling of the case at the Magistrate's Court that he had decided to retain him for the trial. On the other hand Mr. Burge is of the same seniority as many Q.C.s and considered to be the leading junior criminal counsel at the Bar. He is a jovial, sunshiney, Pickwickian sort of man, who always seems to be smiling. It was not entirely coincidence, I thought, that some of his practice was devoted to licensing cases. Beer and Burgundy seemed to blend with his beaming face.

In short, Mr. Burge was a very nice man; indeed, as the trial went on, I began to think that alongside Mr. Griffith-Jones, he was almost too nice a man. He was a civilised being, a person of wit and humour. I had been told by one of his colleagues that he was one of the few men at the Bar who could laugh a case out of court. The atmosphere here, as I think he realised, was not conducive to this sort of approach, but I was told he had tried it once or twice at the Magistrate's Court with some success. In addition to his quip about Mr. Griffith-Jones making a honeymoon sound obscene, he had also said that he had no objection to some of Mr Griffith-Jones's leading questions, as they were not leading very far. Mr. Griffith-Jones himself would have been incapable of either of these two remarks. But equally Mr. Burge could not match Mr. Griffith-Jones's cold relentless plodding, his battering away at the walls until, by sheer persistence, they began to crack. It was this, in the last analysis, that made one admire Mr. Griffith-Jones as much as one deplored him. Because his own attitude to the case was committed, one became committed in one's attitude towards him. It was this outward lack of commitment, not in matter but in manner, that at times led one to feel that Mr. Burge was doing himself literally less than justice. They say that the days of the committed lawyer are over: yet one would have liked to see Ward's defence accompanied by some passion, with his counsel as contemptuous of the

charges laid against him as the prosecution were contemptuous of Ward himself. As it was, while I had no doubts which of the two counsel was the more intelligent, urbane and congenial, equally I had no doubts, where the jury was concerned, which was the more effective advocate.To be fair to Mr. Burge he was labouring under certain handicaps. The first was that the judge did not appear- I do

not say he wasn't-as sympathetic to the presentation of the case for the defence as he was to the case for the prosecution. His odd little trick, when addressing Mr. Burge, of allowing a noticeable pause between "Mr." and "Burge" has already been noted.There were other instances, and they increased as the trial went on, when various remarks he made and the moment at which he made them had the effect of taking the edge off what Mr. Burge was saying. He did not do this, or he did not do it so often, with Mr. Griffith-Jones.

Mr. Burge's other great handicap was his inability to hear much of what the witnesses were saying. Miss Christine Keeler was only the first of many female witnesses who gave their evidence in a whisper. Again and again Mr. Burge found himself saying: "You went where?" - "What do you say he was doing?" -"You said what?" Often he repeated the witnesses' answers so as to be sure that he had heard right: often he heard wrong, so that the witnesses had to repeat themselves. But sometimes, while they were drawing breath to repeat themselves, the judge, who was halfway between Mr. Burge and the witness-box, saved them the trouble by relaying their answers for them. He did this, I thought, in a most unfortunate manner, raising his voice and enunciating each syllable, as though talking to a backward child. Psychologically, all of this combined to put Mr. Burge at a slight disadvantage. Nor was he helped by Ward's blow-by-blow comments on the trial which came tumbling over the dock wall in a seemingly endless stream of little pieces of paper.

Mr. Burge's object with Christine Keeler was to show that she was less a prostitute than what the Americans call a "party girl". Here he found himself in the odd position for a counsel of cross-examining a witness who was only too happy to agree with him; and his task in this respect was as easy as Mr. Griffith-Jones' had been difficult.

"You know the prosecution are endeavouring to prove that Ward had been living on the earnings of prostitution?"

"Yes, I do."

"When you were living at 17 Wimpole Mews, is it right to say you were frequently hard up for money?" "Yes."

"And Ward gave you spending money?" "Yes."

"It is quite obvious to anyone who has seen you, if you wished to earn money by selling your body you could have made very large sums of money?"

"Yes." Miss Keeler looked suitably flattered. Mr. Burge repeated "Yes" after her, and glanced round the court almost as if to say, "There, you see! This girl isn't a tart at all".

(2) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Griffith-Jones had more success with Christine Keeler on the charges against Ward to do with procuring. She confirmed Griffith-Jones's account of how Ward had got her to approach Miss R., the shop assistant, and Sally Norie in the restaurant. And he managed to imply that these were not isolated instances. "You are telling us that it became the understood thing that you find girls for him?" he asked Keeler. "Yes," she replied. In case the jury began to wonder why Keeler had therefore not also been charged with procuring, the judge explained that the prosecution had given an undertaking not to take action against her.

Ward's counsel, James Burge, then rose to cross-examine Keeler. His approach was very much to the point. "You know the prosecution are endeavouring to prove that Ward had been living on the earnings of prostitution?" Keeler said she did. "When you were living at 17 Wimpole Mews, is it right to say that you were frequently hard up for money?" Keeler replied, "Yes." Burge went on to elicit from Keeler that she was living rent-free at Ward's flat, and had the use of telephone, lights and hot water. However, when she had money she sometimes made small payments to Ward. "But you never returned to the accused as much as you got from him?" Burge asked. Keeler's answer was firm. "No," she said.

(3) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

When Ronna Ricardo, who had provided strong evidence against him at the early hearing, came into court she swore under oath that her earlier evidence had been false. She had lied to satisfy the police, that they had threatened her, if she refused, with taking her baby and her young sister into care. Despite the most aggressive attack from Mr Griffith Jones, and barely concealed hostility from the judge, she stuck to her story, that this was the truth and the earlier story she had told was lies.

The other prostitutes, Vickie Barrett (she had not been produced at the earlier hearing, and Mr Burge, Stephen's counsel, protested but was over-ruled), gave evidence of being picked up by Stephen and taken back to Bryanston Mews, where she had intercourse with men waiting there. She gave explicit details about being required also to `whip' with "canes" and "horse whips". Much of what she said was discredited. It was obvious to anyone that Stephen, with the police breathing down his neck and the press on his doorstep, would hardly have the opportunity or the inclination for this sort of thing. She was completely suspect to the majority of people in the court, except presumably judge Marshall who, in his summing up, appeared to give weight and credence to her evidence. (In the event, after the trial she retracted, and said that she too had been pressurised by the police who threatened her with nine months inside for soliciting if she didn't co-operate. Perhaps she didn't need much persuasion. To be involved in this society scandal was a step up the ladder - like a pavement artist being linked with Picasso!)

None of this helped Stephen. I had an overwhelming desire to stand up and scream for what they were doing to him. I had to clench my teeth to stop myself shouting out. I was afraid. I couldn't believe what was happening, as if some malevolent force was taking over and we were powerless. Somebody like me had no hope of fighting back. My only hope was to stay calm, get through it somehow, have it all behind me.

I could see now that before the trial began I had underestimated the seriousness of events. I'd told myself that the magistrates' hearing was one thing, rather amateur really, but once we got to the Old Bailey the real wheels of justice would be set in motion and they don't roll over the innocent, do they? Not that we claimed to be innocent in a strictly moral sense. It is extraordinary to think back to how easily shocked most people were in 1963. Before the page 3 nude and sex on TV right there in your living-room, people were sheltered, I suppose. When Christine said in court that she had had an abortion, there was a gasp from the court. People didn't hear that word too often.

I hated Griffith Jones. If ever anyone deserved a custard pie in his face, he did. I thought he was a hypocrite. If he practised what he preached, then he was undoubtedly too good for this world. He belonged in a Victorian melodrama, was cold and cutting.

"Did you have intercourse with Lord Astor?"

"Yes."

"Did he give you £200?"

"Yes - but - "

"No buts. Answer the question, yes or no."

By the time the defence, Mr Burge, could extract the information that there was a two-year interval between my receiving £200 from Bill Astor and my going to bed with him, which by any standards alters the emphasis entirely, the damage had been done.

I lunched with Christine one day during the trial at a pub near the Old Bailey. It was the first time we had spoken deeply. We were both appalled at what was happening; Christine in a way blamed herself for telling the police so much, but I could understand how it happened. When the police want something they usually get it. What was so frustrating was that the press, the lawyers, everyone was saying the trial was a farce, and yet here it was, taking its course. It was almost a joke in the media.

Like the Osbert Lancaster cartoon in the Daily Express. One man saying to the other: "If I give my wife's lover the winner of the 4.30 would I be living off her immoral earnings?" I still cannot understand why I was ever called a "call girl". Promiscuous, perhaps, but not a call girl. I was Rachman's mistress, that doesn't make me a call girl. I had men friends I went to bed with, but they were friends. A call girl goes to bed with strangers. If I had been passionately, madly in love with every man in my life, would that have altered things? If a woman goes to bed with her husband, not because she passionately fancies him but rather than upset the status quo, does that impugn her morality? I tried to express myself to the judge, but every time I went to open my mouth he would say: "Stick to the questions, or I'll have you for contempt of court."

At one point the judge, trying to establish whether or not I had sex in return for money asked me, "What was the quid pro quo?' I stood there speechless with indignation that he should be so supercilious as to address a witness in Latin. It so happened I knew what he was asking. He mistook my silence.

"That means what did you give in return," he said testily.

It is my lasting regret that I didn't reply, "Amora, you silly old fool. Amora. That's Latin for love, don't you know?"

Sex for money. Love for money? Where do you draw the thin red line? Where are the borders? I've asked myself this question a thousand times, and I don't know the answer. I believe I am fairly honest, and I deserved some of the mud thrown at me. I went through life superficially, guided on two levels - one by the comforts I came to enjoy, and the other by feeling I might be missing something. Maybe I sacrificed moral integrity for comfort.

The trial lasted over a week. On Tuesday of the second week, 30 July, the judge began his summing up. We knew there was no hope. Much was made of the fact that in his hour of need none of Stephen's good friends came forward as a character witness. They didn't because Stephen asked them not to. He was embarrassed at involving them needlessly, he believed. When the investigations began he couldn't believe they would lead anywhere, and he insisted his friends stay out of it. Bill Astor certainly volunteered, and probably others did, too. By the time he knew he needed help, the fat was in the fire. My father always said he regretted not coming forward. That would have made news - Father appearing for the defence, his daughter for the prosecution.

That evening Stephen went back to the flat in Chelsea where he was a guest during the trial. He wrote several letters - including one to Vickie Barrett - to be delivered "only if I am convicted and sent to prison". He cooked a meal for himself and his girlfriend, Julie Gulliver, then drove her home. He drove around for a while, possibly thinking things over, then, his mind made up, went back to the flat. He wrote another letter, to his friend and host Noel Howard Jones, and swallowed an overdose of nembutal.

(4) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Burge had shown that Vickie Barrett was not averse to telling lies when it suited her. He now recalled that Christine Keeler did the same. To counter Christine's evidence that Ward had introduced her to marijuana, he had earlier asked her whether, on the contrary, Ward was so concerned about her use of it that he had taken her to Scotland Yard for counselling by officers of the narcotics squad. Keeler had denied that such a visit had ever taken place. Now Burge confronted her with a statement from the narcotics officer who had advised her, confirming the visit. Trapped in the lie, Keeler reluctantly admitted the truth.

That ended the prosecution case. How strong was it? Griffith-Jones had succeeded in establishing that Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies took money for sex. He had shown that both girls gave money to Ward. Even though, given that in law the dividing line between living with a prostitute and living on a prostitute is very thin, the prosecution's weak point was that both girls owed Ward - one way or another - far more money than they ever paid him. In his opening speech Griffith-Jones had said of Ward, "Whatever the extent of his earnings for this period may have been, from the evidence you will hear, and indeed from what he has told the police, they were quite obviously not sufficient for what he was spending." Yet no evidence had been brought to show this at all; in fact the police admitted that they had been unable to find out what Ward's earnings were. Ronna Ricardo had gone back on her evidence given in the Magistrate's Court and Vickie Barrett's evidence was somewhat suspect because she had been shown as willing to lie if she felt it necessary. The two procuring charges had been exposed as ludicrous. Ward must have been feeling cautiously optimistic as his counsel, James Burge, rose to open the case for the defence.

(5) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Ward had given a good account of himself. But the jury was less influenced by his carefully-worded replies than by two damaging questions put to him, one by Griffith-Jones and one by the judge. In the middle of Ward's admission that he had picked up a prostitute, Griffith-Jones suddenly said, "Are your sexual desires absolutely insatiable?" Ward answered carefully, "I don't think I have more sexual relationships than any other people of my age, but possibly the variety is greater."

Then, just as Ward was about to leave the witness box, the judge said, "Dr Ward, when do you say a woman is a prostitute?" Ward thought for a moment and then replied, "It is a very difficult question to answer, but I would say when there is no element in the relationship between the man and the woman except a desire on the part of the woman to make money, when it is separated from any attachment and indeed is just a sale of her body." The judge pressed Ward further. "If anyone does receive a payment when the basis is sexual is she not in your view a prostitute?" he asked. Ward said that when sentiment or other factors entered into the relationship, it became a more permanent relationship, like a kept woman. "You cannot possibly refer to such a woman as a prostitute," he said.

The significance of this exchange was not lost on the jurors. The judge's questions had made it clear that in his view a kept woman was as much a prostitute as a woman who plied the streets, whereas Ward's view was that kept women were no more prostitutes than women who married for money. In the judge's view, therefore, both Christine and Mandy were prostitutes. And since Ward was living with them, the onus was on him to prove that he was not living off them. In Ward's view the girls were not prostitutes. The jurors would have to decide which view they would accept...Burge now made his closing speech for the defence. He began by reminding the jury what the case was not about. "If this trial was concerned with establishing that Ward led a thoroughly immoral life, a demoralised and undisciplined life, your task would be a simple one. No one has thought to disguise that fact from you. If you wanted to make sure that the public conscience was shamed by a major scandal and should be appeased, and the penalty should be paid, you would hardly find a more suitable subject for expiation than Ward, who has admitted he is a loose liver and whose conduct is such as to deprive him of any sympathy from any quarter."

But the case was about whether Ward was living off prostitutes' earnings, Burge said. If Ward had been living off Christine Keeler's earnings one would have expected her to be loaded with money and not have to borrow off him. Keeler was not to be trusted to tell the truth, he said. The Lucky Gordon appeal would show that. There were many reasons why Christine might be lying. "Indeed, after all the interviews she had with the police and the Press she might, quite genuinely by now, be unable to distinguish between truth and fiction," Burge said. As for Mandy Rice-Davies, the £6 a week which Mandy paid Ward for the bedroom at Wimpole Mews was a reasonable rent. "Just as a lawyer or a greengrocer who receives a reasonable remuneration for services they are giving to a prostitute - not as a prostitute but as an ordinary person - is not guilty of living on her immoral earnings, so, in my submission Ward was not living on her immoral earnings if she was a prostitute."

Burge said that for the prosecution to make its case, Keeler and Rice-Davies's evidence required corroboration. Ricardo's original evidence had done that but she had retracted it. Then, conveniently, Vickie Barrett had come on the scene. "She turned up, did she not, at a very opportune moment for the prosecution. She comes out of the blue, just when she is wanted, on the very day of Ward's committal. She tells the story of an absolutely conventional ponce, which is entirely different to anything else in this case. A key witness emerges for the prosecution because there were great difficulties about the case of Miss Keeler and Miss Rice-Davies. What a turn-up for the book. I suggest to you it is too good to be true." Burge reminded the jury of the evidence of Frances Brown, a prostitute who had volunteered to give evidence for Ward after reading about Barrett's testimony in the newspapers. Brown had said that she had been soliciting with Barrett nearly every night and would have known if Barrett had been going regularly to Ward's flat.

What, then, had been the role of the police in this matter? Burge was too experienced in courtroom tactics to accuse the police outright of framing Ward. But he managed to convey to the jurors that the police, too, had been under pressure during the Ward investigation. "An important element in this case is that at the time the investigations started, public indignation had mounted following certain scandals. It was quite clear that something had to be done. Obviously the highest authorities were concerned with this investigation. It was a situation in which the police officers can either make their names or sink into oblivion. It is obviously a matter which they could go into with the knowledge of what was behind it and the knowledge that they have to do their very best to provide a case," Burge said.

"A man would be clearly not human if he were not influenced in the enthusiasm of his inquiry by these considerations. The police officers have allowed their enthusiasm and the fear of the possibilities of failure, to spur on their investigation of the various witnesses and to colour their evidence in the interpretation of facts that are alleged to have been said on June 8 (the interview with Ward)."

Burge had one last point to make, the one he considered to be the key to the case. "Was this life of Ward's led for fun or for profit?" he asked. "Was he conducting a business, living as a parasite on the earnings of prostitution? It is a very, very wide gap and a big step between a man with an artistic temperament and obviously with high sexual proclivities leading a dissolute life, and saying he has committed the offence of living on the earnings of prostitution. On a fair and impartial view I will ask you to say that these charges have not been made out and find him not guilty."

The prosecution in the criminal case in England has the advantage of the first and the last word. We have seen how Griffith-Jones took full advantage of his opening speech to blacken Ward's character. He now used this second chance to twist the knife. His closing address was not so much a review of the evidence as a story, a vividly told, cleverly constructed account of the life of Stephen Ward and his relationship with the women in the case. He used phrases and expressions more appropriate to a soap opera and he delivered them with an actor's skill. Stephen Ward became "this filthy fellow"; Christine and Mandy became "two girls of sixteen, recently in London from their homes in the country"; when Christine left Wimpole Mews and Mandy moved in, Ward was "changing mounts".

(6) James Burge, concluding statement in the trial of Stephen Ward (30th July, 1963)

My learned friend, when he opened the case, referred to introductions - introductions which were intended to bear sinister significance - the introduction of a man to a woman. He said the accused introduced Miss Keeler to Rachman and then he said 'Forget it'.

You may have made a mental note that if it had nothing to do with the case, why was it mentioned at all, and why immediately after you were asked to forget it.

If you read the Press you would have seen such headlines as "Ward Introduces Rachman to Keeler". That is the danger in this case. There was no question of an introduction of Miss Keeler to Rachman for the purposes alleged by the prosecution, and in fact it was a chance meeting.

I won't go through every instance, but I only mentioned that in order to show the enormous danger of substituting fiction for fact in this case, rumour for evidence and prejudice for real substance, because this case absolutely reeks of it.

You and only you preserve the balance between a man who is charged with a series of revolting offences and a prosecution which is based more largely, you might think, upon prejudice than actual evidence.

You may have noticed that I raised various objections during the course of the case and you may have thought "Well, really, this is the sort of thing that doesn't appeal to us, a lawyer getting up and talking lawyer's points and interrupting the prosecution and so on". I couldn't agree with you more. That is not the sort of thing that any sensible and experienced advocate would wish to do.

For months on end following the declaration in the House of Commons on March 22nd, the police have combed the country in a frenzy in order to find evidence implicating the accused.

You have heard of the number of witnesses that have been interviewed, and you have seen some of them, and you have heard the circumstances and places in which they were interviewed.