Mervyn Griffith-Jones

Mervyn Griffith-Jones, the son of the barrister, John Stanley Phillips Griffith-Jones and Eveline Yarrow Griffith-Jones, was born on 1st July 1909, at 19 Kidderpore Gardens, Hampstead, London. He was educated at Eton College and Trinity Hall and after leaving the University of Cambridge he trained as a lawyer. He was called to the bar by the Middle Temple in 1932 where he acquired a good criminal practice.

On the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 Griffith-Jones joined the Coldstream Guards. His biographer, Michael Beloff, has pointed out: "Mervyn Griffith-Jones... served with distinction in the western desert and in Italy. He was mentioned in dispatches and awarded the Military Cross in 1943; in a later memoir by a then newly commissioned officer he was remembered for his bravery and selfless concern for those who served under him. After the war his two streams of adult experience came together when he was instructed as one of five junior barristers in the British prosecuting team at the Nuremberg war crimes trial. Dressed in the conventional garb of black jacket and striped trousers, he - and his co-counsel - exhibited the common law art of cross-examination at its best." Griffith-Jones was especially praised for his questioning of Julius Steicher. According to Michael R. Marrus, the author of The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial 1945-46 (1997): "Streicher's testimony and cross examination were noteworthy mainly for what they revealed about the accused - a course, garrulous, repulsive fanatic whom even Nazi loyalists found embarrassing."

In 1946 Griffith-Jones returned to private practice, setting up his own chambers at 2 Harcourt Buildings, Temple, London, where he specialized as a prosecutor. Griffith-Jones served as counsel for the crown, first at north London sessions (1946–50) and then at the central criminal court, the Old Bailey. He developed a reputation as a conservative reactionary. Ludovic Kennedy commented: "Square is the word that suits him. He is so ultra-orthodox that some aspects of modern life have escaped him altogether."

In 1954 Griffith-Jones became involved in a very controversial case. The previous year Walter Baxter published his second novel, The Image and the Search. The main character, Sarah, is happily married but after the death of her husband in the war, she takes several lovers. E. M. Forster described it as "a serious and beautiful book", however, Lord Beaverbrook, wrote an article in the Sunday Express, where he condemned the message that "sexual excess can be indulged in with a light heart and a clear conscience". Beaverbrook then suggested that Alexander Stewart Frere, the chairman of the book's publisher Heinemann, should immediately withdraw the book. The company agreed to do this and admitted that "the Sunday Express' attack has succeeded in having the book banned. We regard this as an extremely unfortunate case of arbitrary censorship."

It was decided to charge Baxter and Frere under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. The case, that began in October, 1954, was prosecuted by Mervyn Griffith-Jones. Frere argued: "I regard Walter Baxter as one of the most gifted writers of this generation, whose powers are not yet fully developed. I feel that the publishers owe a duty to such writers and to the public to ensure that their creative work is not still-born. If it has value and is not deleterious to potential readers, I was, and am myself, satisfied that this book would not harm any readers." When the jury could not reach agreement after two trials, the defendants were acquitted. Baxter never published another novel.

In June 1955 he was one of the prosecuting team at the trial of Ruth Ellis. She had been charged with murdering her boyfriend, David Blakely, on 10th April, 1955. The jury took 14 minutes to convict her and she was sentenced to death. However, the judge in the case, Cecil Havers, wrote to the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George suggesting a reprieve as he regarded it as a "crime passionnel". However, he rejected the advice and she was executed on 13th July. She was the last woman executed in Britain and it is claimed that the case helped to bring an end to capital punishment.

In 1959, the Labour Party MP, Roy Jenkins, introduced a private member's bill, that aimed to change the 1857 Obscene Publications Act that had successfully forced the banning of The Image and the Search. Jenkins persuaded Parliament to pass a new Obscene Publications Act. Before 1959 obscenity had been a common-law offence, as defined by the lord chief justice in 1868, extending to all works judged to "deprave and corrupt" those open to "such immoral influences". Under the new act works were to be considered in their entirety and could be defended in terms of their contribution to the public good; after 1959 those convicted of obscenity would also face limited (in contrast to previously unlimited) punishments of a fine or up to three years' imprisonment.

As a result of this legislation, Sir Allen Lane, the chairman of Penguin, agreed to publish an unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, a novel that had been written by D.H. Lawrence in 1926. The initial print was 200,000 copies. Alerted to Penguin's intention to publish the novel, Sir Theobald Mathew, the director of public prosecutions, decided to prosecute the firm under the act of 1959. It was a move welcomed by Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, the Conservative government's attorney-general, who expressed the hope that "you get a conviction".

Mervyn Griffith-Jones was selected as the prosecuting counsel in the trial that was held at the Old Bailey between 20th October and 2nd November 1960. Michael Beloff has commented: "From the outset Griffith-Jones's hostility to the unexpurgated edition was apparent to those observing this high-profile test case of the new legislation." One observer, the journalist, Sybille Bedford, commented on a "voice quivering with thin-lipped scorn".

In his opening statement Griffith-Jones advised jury members that they must answer two questions: first, whether the novel, taken as a whole, was obscene in terms of section 2 of the new legislation ("to deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read the matter contained in it") and, second, if this proved so, whether publication was still justified for the public good. "You may think that one of the ways in which you can test this book, and test it from the most liberal outlook, is to ask yourselves the question, when you have read it through, would you approve of your young sons, young daughters - because girls can read as well as boys - reading this book. Is it a book that you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?" C. H. Rolph later argued that the question "had a visible - and risible - effect on the jury, and may well have been the first nail in the prosecution's coffin".

Witnesses for the defence included several academics Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams, Graham Goulder Hough, Helen Gardner, Vivian de Sola Pinto, Kenneth Muir and Noel Annan. They were accompanied by thirteen authors and journalists, including Rebecca West, E. M. Forster, Francis Williams, Walter Allen, Anne Scott-James, Dilys Powell, Cecil Day Lewis, Stephen Potter, Janet Adam Smith; John Henry Robertson Connell and Alastair Hetherington. Other defence witnesses included John Robinson, the Bishop of Woolwich.

In his closing speech, Mervyn Griffith-Jones questioned whether the opinions of university lecturers and writers were those of the "ordinary common men and women" who would read Penguin's cheap paperback edition, and reiterated that the novel contained depictions of sexual activity of the kind that could only be found "some way in the Charing Cross Road, the back streets of Paris and even Port Said". Griffith-Jones's efforts were in vain and on 2nd November, 1960, the jurors returned a verdict of not guilty, so opening the way for the legal distribution of novels that had previously been considered obscene. The book went on sale on 10th November, at 3s. 6d., and by the end of the first day the complete run of 200,000 copies had been sold. Within a year of its publication, this edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover had sold more than 2 million copies.

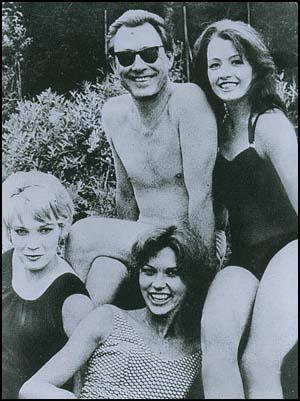

In April, 1963, Dr. Stephan Ward was accused of living off the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies. Mervyn Griffith-Jones was selected as the head of the prosecution team. The trial of Stephen Ward began at the Old Bailey on 22nd July 1963. Keeler admitted in court that she had sex with John Profumo, Charles Clore and Jim Eynan. In all three cases the men gave her money and gifts. During cross-examination she confessed that some of this money was paid to Ward as she owed him money for rent, electricity and food while she was living at his flat.

Rice-Davies also admitted receiving money and gifts from Peter Rachman and Emil Savundra. As she was living with Ward at the time she gave him some of this money for unpaid rent. As Rice-Davies pointed out: "Much was made of the fact that I was paying him a few pounds a week whilst I was living in Wimpole Mews. But I said before and say it again - Stephen never did anything for nothing and we agreed on the rent the day I arrived. He most certainly never influenced me to sleep with anyone, nor ever asked me to do so." She added: "Stephen was never a blue-and-white diamond, but a pimp? Ridiculous.... As for Christine, she was always borrowing money (from Stephen Ward)."

Ludovic Kennedy, the author of The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964) has argued that Ward's defence counsel, James Burge, was unable to compete with Griffith-Jones: "In short, Mr. Burge was a very nice man; indeed, as the trial went on, I began to think that alongside Mr. Griffith-Jones, he was almost too nice a man. He was a civilised being, a person of wit and humour. I had been told by one of his colleagues that he was one of the few men at the Bar who could laugh a case out of court. The atmosphere here, as I think he realised, was not conducive to this sort of approach, but I was told he had tried it once or twice at the Magistrate's Court with some success. In addition to his quip about Mr. Griffith-Jones making a honeymoon sound obscene, he had also said that he had no objection to some of Mr Griffith-Jones's leading questions, as they were not leading very far. Mr. Griffith-Jones himself would have been incapable of either of these two remarks. But equally Mr. Burge could not match Mr. Griffith-Jones's cold relentless plodding, his battering away at the walls until, by sheer persistence, they began to crack. It was this, in the last analysis, that made one admire Mr. Griffith-Jones as much as one deplored him. Because his own attitude to the case was committed, one became committed in one's attitude towards him. It was this outward lack of commitment, not in matter but in manner, that at times led one to feel that Mr. Burge was doing himself literally less than justice. They say that the days of the committed lawyer are over: yet one would have liked to see Ward's defence accompanied by some passion, with his counsel as contemptuous of the charges laid against him as the prosecution were contemptuous of Ward himself. As it was, while I had no doubts which of the two counsel was the more intelligent, urbane and congenial, equally I had no doubts, where the jury was concerned, which was the more effective advocate."

Christine Keeler took a strong dislike to both Griffith-Jones and Justice Archibald Pellow Marshall. "How I hated those evil men going about their bad business in those toffee-voiced tones". Mandy Rice-Davies agreed with Keeler: "I hated Griffith Jones. If ever anyone deserved a custard pie in his face, he did. I thought he was a hypocrite. If he practised what he preached, then he was undoubtedly too good for this world. He belonged in a Victorian melodrama, was cold and cutting."

In his cross-examination of Stephan Ward, Burge asked him about his annual income. Ward replied that he was earning about £4,000 from his practice and another £1,500 or so from his drawings - a total of between £5,000 and £6,000 a year. Burge then asked: "If the prosecution's picture of a man procuring, and the picture of people in high places and very wealthy men was true, would you have needed to carry on your practice and work as an osteopath?" Ward replied: "If that were true, evidently not."

Philip Knightley, the author of An Affair of State (1987) pointed out: "That ended the prosecution case. How strong was it? Griffith-Jones had succeeded in establishing that Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies took money for sex. He had shown that both girls gave money to Ward. Even though, given that in law the dividing line between living with a prostitute and living on a prostitute is very thin, the prosecution's weak point was that both girls owed Ward - one way or another - far more money than they ever paid him."

At the end of the case, Stephan Ward told James Burge: "One of my great perils is that at least half a dozen of the (witnesses) are lying and their motives vary from malice to cupidity and fear... In the case of both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies there is absolutely no doubt that they are committed to stories which are already sold or could be sold to newspapers and that my conviction would free these newspapers to print stories which they would otherwise be quite unable to print (for libel reasons)."

Stephen Ward was very upset by the judge's summing-up that included the following: "If Stephen Ward was telling the truth in the witness box, there are in this city many witnesses of high estate and low who could have come and testified in support of his evidence." Several people present in the court claimed that Judge Archie Pellow Marshall was clearly biased against Ward. France Soir reported: "However impartial he tried to appear, Judge Marshall was betrayed by his voice."

After the day's court proceedings, Ward contacted Tom Critchley, a Home Office official working with Lord Denning on the official investigation. Later, Critchley refused to comment what was said in that telephone conversation. That night Ward met the journalist Tom Mangold: "Stephen was very relaxed... He wasn't walking around in a froth. He was very calm and collected, just writing his letters and putting them in envelopes. I wanted to pretend that I hadn't seen what I'd seen. My excuse, which was not a good excuse, was that I was on a yellow card from my wife. I reckoned I could risk being home two hours late. But I knew the marriage wouldn't survive if I showed up any later. So all I did was to bleat at Stephen not to do anything foolish."

After Mangold left Stephan Ward wrote to his friend, Noel Howard-Jones: "It is really more than I can stand - the horror, day after day at the court and in the streets. It is not only fear, it is a wish not to let them get me. I would rather get myself. I do hope I have not let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff but after Marshall's summing-up, I've given up all hope." Ward then took an overdose of sleeping tablets. He was in a coma when the jury reached their verdict of guilty of the charge of living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies on Wednesday 31st July. Three days later, Ward died in St Stephen's Hospital. It is claimed that Griffith-Jones cried when he heard the news. Burge's friend, Sir David Napley later commented: "When Ward committed suicide, Jimmy Burge was very affected. He never seemed to be the same man again... It was not long after this that he left the bar and took up residence abroad."

Mervyn Griffith-Jones died of renal failure at St Stephen's Hospital, London, on 13th July 1979.

Primary Sources

(1) Ludovic Kennedy, The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964)

It was now the turn of Ward's defence counsel, Mr. James Burge. Mr. James Burge was not a Q.C., as might have been expected in a case of this importance, and I understood that that was because Ward had been so pleased with his handling of the case at the Magistrate's Court that he had decided to retain him for the trial. On the other hand Mr. Burge is of the same seniority as many Q.C.s and considered to be the leading junior criminal counsel at the Bar. He is a jovial, sunshiney, Pickwickian sort of man, who always seems to be smiling. It was not entirely coincidence, I thought, that some of his practice was devoted to licensing cases. Beer and Burgundy seemed to blend with his beaming face.

In short, Mr. Burge was a very nice man; indeed, as the trial went on, I began to think that alongside Mr. Griffith-Jones, he was almost too nice a man. He was a civilised being, a person of wit and humour. I had been told by one of his colleagues that he was one of the few men at the Bar who could laugh a case out of court. The atmosphere here, as I think he realised, was not conducive to this sort of approach, but I was told he had tried it once or twice at the Magistrate's Court with some success. In addition to his quip about Mr. Griffith-Jones making a honeymoon sound obscene, he had also said that he had no objection to some of Mr Griffith-Jones's leading questions, as they were not leading very far. Mr. Griffith-Jones himself would have been incapable of either of these two remarks. But equally Mr. Burge could not match Mr. Griffith-Jones's cold relentless plodding, his battering away at the walls until, by sheer persistence, they began to crack. It was this, in the last analysis, that made one admire Mr. Griffith-Jones as much as one deplored him. Because his own attitude to the case was committed, one became committed in one's attitude towards him. It was this outward lack of commitment, not in matter but in manner, that at times led one to feel that Mr. Burge was doing himself literally less than justice. They say that the days of the committed lawyer are over: yet one would have liked to see Ward's defence accompanied by some passion, with his counsel as contemptuous of the

charges laid against him as the prosecution were contemptuous of Ward himself. As it was, while I had no doubts which of the two counsel was the more intelligent, urbane and congenial, equally I had no doubts, where the jury was concerned, which was the more effective advocate.To be fair to Mr. Burge he was labouring under certain handicaps. The first was that the judge did not appear-I do

not say he wasn't-as sympathetic to the presentation of the case for the defence as he was to the case for the prosecution. His odd little trick, when addressing Mr. Burge, of allowing a noticeable pause between "Mr." and "Burge" has already been noted.There were other instances, and they increased as the trial went on, when various remarks he made and the moment at which he made them had the effect of taking the edge off what Mr. Burge was saying. He did not do this, or he did not do it so often, with Mr. Griffith-Jones.

Mr. Burge's other great handicap was his inability to hear much of what the witnesses were saying. Miss Christine Keeler was only the first of many female witnesses who gave their evidence in a whisper. Again and again Mr. Burge found himself saying: "You went where?" - "What do you say he was doing?" -"You said what?" Often he repeated the witnesses' answers so as to be sure that he had heard right: often he heard wrong, so that the witnesses had to repeat themselves. But sometimes, while they were drawing breath to repeat themselves, the judge, who was halfway between Mr. Burge and the witness-box, saved them the trouble by relaying their answers for them. He did this, I thought, in a most unfortunate manner, raising his voice and enunciating each syllable, as though talking to a backward child. Psychologically, all of this combined to put Mr. Burge at a slight disadvantage. Nor was he helped by Ward's blow-by-blow comments on the trial which came tumbling over the dock wall in a seemingly endless stream of little pieces of paper.

Mr. Burge's object with Christine Keeler was to show that she was less a prostitute than what the Americans call a "party girl". Here he found himself in the odd position for a counsel of cross-examining a witness who was only too happy to agree with him; and his task in this respect was as easy as Mr. Griffith-Jones' had been difficult.

"You know the prosecution are endeavouring to prove that Ward had been living on the earnings of prostitution?"

"Yes, I do."

"When you were living at 17 Wimpole Mews, is it right to say you were frequently hard up for money?" "Yes."

"And Ward gave you spending money?" "Yes."

"It is quite obvious to anyone who has seen you, if you wished to earn money by selling your body you could have made very large sums of money?"

"Yes." Miss Keeler looked suitably flattered. Mr. Burge repeated "Yes" after her, and glanced round the court almost as if to say, "There, you see! This girl isn't a tart at all".

(2) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Griffith-Jones had more success with Christine Keeler on the charges against Ward to do with procuring. She confirmed Griffith-Jones's account of how Ward had got her to approach Miss R., the shop assistant, and Sally Norie in the restaurant. And he managed to imply that these were not isolated instances. "You are telling us that it became the understood thing that you find girls for him?" he asked Keeler. "Yes," she replied. In case the jury began to wonder why Keeler had therefore not also been charged with procuring, the judge explained that the prosecution had given an undertaking not to take action against her.

Ward's counsel, James Burge, then rose to cross-examine Keeler. His approach was very much to the point. "You know the prosecution are endeavouring to prove that Ward had been living on the earnings of prostitution?" Keeler said she did. "When you were living at 17 Wimpole Mews, is it right to say that you were frequently hard up for money?" Keeler replied, "Yes." Burge went on to elicit from Keeler that she was living rent-free at Ward's flat, and had the use of telephone, lights and hot water. However, when she had money she sometimes made small payments to Ward. "But you never returned to the accused as much as you got from him?" Burge asked. Keeler's answer was firm. "No," she said.

(3) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

I hated Griffith Jones. If ever anyone deserved a custard pie in his face, he did. I thought he was a hypocrite. If he practised what he preached, then he was undoubtedly too good for this world. He belonged in a Victorian melodrama, was cold and cutting.

"Did you have intercourse with Lord Astor?"

"Yes."

"Did he give you £200?"

"Yes - but - "

"No buts. Answer the question, yes or no."

By the time the defence, Mr Burge, could extract the information that there was a two-year interval between my receiving £200 from Bill Astor and my going to bed with him, which by any standards alters the emphasis entirely, the damage had been done.

(4) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Ward had given a good account of himself. But the jury was less influenced by his carefully-worded replies than by two damaging questions put to him, one by Griffith-Jones and one by the judge. In the middle of Ward's admission that he had picked up a prostitute, Griffith-Jones suddenly said, "Are your sexual desires absolutely insatiable?" Ward answered carefully, "I don't think I have more sexual relationships than any other people of my age, but possibly the variety is greater."

Then, just as Ward was about to leave the witness box, the judge said, "Dr Ward, when do you say a woman is a prostitute?" Ward thought for a moment and then replied, "It is a very difficult question to answer, but I would say when there is no element in the relationship between the man and the woman except a desire on the part of the woman to make money, when it is separated from any attachment and indeed is just a sale of her body." The judge pressed Ward further. "If anyone does receive a payment when the basis is sexual is she not in your view a prostitute?" he asked. Ward said that when sentiment or other factors entered into the relationship, it became a more permanent relationship, like a kept woman. "You cannot possibly refer to such a woman as a prostitute," he said.

The significance of this exchange was not lost on the jurors. The judge's questions had made it clear that in his view a kept woman was as much a prostitute as a woman who plied the streets, whereas Ward's view was that kept women were no more prostitutes than women who married for money. In the judge's view, therefore, both Christine and Mandy were prostitutes. And since Ward was living with them, the onus was on him to prove that he was not living off them. In Ward's view the girls were not prostitutes. The jurors would have to decide which view they would accept.

(5) Vickie Barrett, cross-examined by Mervyn Griffith-Jones (July 1963)

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: On arrival did he take you into the flat?

Vickie Barrett: Yes.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Was there anybody in the living room?

Vickie Barrett: No.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: What did he say to you?

Vickie Barrett: I asked him where the man was.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: What did he say?

Vickie Barrett: He said he was waiting in the bedroom.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Yes.

Vickie Barrett: Well then he gave me a contraceptive and told me to go to the room and strip and he said he would make coffee.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Did you go into the bedroom?

Vickie Barrett: Yes.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Was there anyone in the bedroom?

Vickie Barrett: Yes, a man.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Where was he?

Vickie Barrett: In bed.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Dressed in anything?

Vickie Barrett: No.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Did you go to bed with him?

Vickie Barrett: Yes.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Did you have sexual intercourse with him?

Vickie Barrett: Yes...

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Was anything more said, while you had coffee, about money?

Vickie Barrett: Yes, Ward said it was all right. He had already received the money.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Did he say how much he had received?

Vickie Barrett: No.

Mervyn Griffith-Jones: Did you agree to him keeping it for you?

Vickie Barrett: Yes.