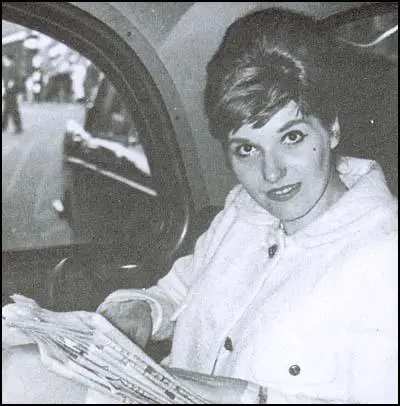

Ronna Ricardo

Margaret (Ronna) Ricardo was born during the Second World War. By the late 1950s she was working as a prostitute in London. She met Stephen Ward in 1960 and he introduced her to Christine Keeler, Mandy Rice-Davies and Suzy Chang. The journalist, Anthony Summers argues in Honeytrap (1987) that "according to the records, both Ricardo and one of her friends had babies by American servicemen".

In her autobiography, The Truth at Last (2001), Christine Keeler describes the first time that Stephen Ward introduced her to Ricardo. "We went to see Ronna Ricardo who had dark hair and almond-shaped, gullible eyes. She was a quiet-spoken, shy girl and I did not know then that she was a busy prostitute." According to Keeler, one of her clients was Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert. Ricardo was known as "Ronna the Lash", and specialised in flagellation. Trevor Kempson, a journalist, who was working for the News of the World claimed: "She used to carry her equipment round in a leather bag. She was well known for the use of the whip, and I heard that several of Ward's friends used to like it rough."

In 1961 Stephen Ward invited Ricardo to stay with him at Cliveden. Ward introduced Ricardo and Christine Keeler to Eugene Ivanov. She later told Anthony Summers: "Christine never went to bed with him (Ivanov)... he was really innocent - he'd never seen anything like it. That was the way they wanted to get someone like him involved. They wanted to blackmail Ivanov. My role in the setup was to look after Ivanov - a minder."

On 7th June, 1963, Christine Keeler told the Daily Express of her secret "dates" with John Profumo. She also admitted that she had been seeing Eugene Ivanov at the same time, sometimes on the same day, as Profumo. In a television interview Stephen Ward told Desmond Wilcox that he had warned the security services about Keeler's relationship with Profumo. The following day Ward was arrested and charged with living off immoral earnings between 1961 and 1963. He was initially refused bail because it was feared that he might try to influence witnesses. Another concern was that he might provide information on the case to the media.

On 14th June, the London solicitor, Michael Eddowes, claimed that Christine Keeler told him that Eugene Ivanov had asked her to get information about nuclear weapons from Profumo. Eddowes added that he had written to Harold Macmillan to ask why no action had been taken on information he had given to Special Branch about this on 29th March. Soon afterwards Keeler told the News of the World that "I'm no spy, I just couldn't ask Jack for secrets."

Ricardo was arrested by the police and agreed to give evidence against Stephen Ward. At the Ward committal proceedings, she provided evidence that suggested that he had been living off her immoral earnings. She quoted Ward as saying that it "would be worth my while" to attend a party at Cliveden. Ricardo claimed that she visited Ward's home in London three times. On one occasion, she had sex with a man in Ward's bedroom after being given £25.

Ricardo told Ludovic Kennedy that the police interviewed her nine times in order that she gave a statement that provided evidence that suggested that Ward was living off immoral earnings. Ricardo confessed to another researcher, Anthony Summers that: "Stephen didn't have to ponce - he was dead rich, a real gentleman; a shoulder for me to cry on for me, for a long time." Ricardo also told Summers that Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert, who was leading the investigation of Ward, was one of her clients.

Two days before Ward's trial, Ricardo made a new statement to the police. "I want to say that most of the evidence I gave at Marylebone Court was untrue. I want to say I never met a man in Stephen Ward's flat except my friend 'Silky' Hawkins. He is the only man I have ever had intercourse with in Ward's flat. It is true that I never paid Ward any money received from men with whom I have had intercourse. I have only been in Ward's flat once and that was with 'Silky'. Ward was there and Michelle."

It later emerged that Ricardo decided to tell the truth after being interviewed by Tom Mangold of the Daily Express. "There were two strands running through the thing, it seemed to me. There was some sort of intelligence connection, which I could not understand at the time. The other thing, the thing that was clear, was that Ward was being made a scapegoat for everyone else's sins. So that the public would excuse them. If the myth about Ward could be built up properly, the myth that he was a revolting fellow, a true pimp, then police would feel that other men, like Profumo and Astor, had been corrupted by him. But he wasn't a ponce. He was no more a pimp than hundreds of other men in London. But when the state wants to act against an individual, it can do it."

The trial of Stephen Ward began at the Old Bailey on 22nd July 1963. Roona Ricardo, was one of the prosecution witnesses, gave evidence on the second day of the trial. Ludovic Kennedy, the author of The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964) commented that unlike Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies "she made no pretentions about not being a tart." Kennedy added "She had dyed red hair and a pink jumper and a total lack of any sort of finesse".

While being cross-examined by Mervyn Griffith-Jones Ricardo claimed she had told untruths about Stephen Ward in her statement on 5th April because of threats made by the police. "The statements which I have made to the police were untrue. I made them because I did not want my young sister to go to a remand home or my baby taken away from me. Mr. Herbert told me they would take my sister away and take my baby if I didn't make the statements."

As Mandy Rice-Davies pointed out: "When Ronna Ricardo, who had provided strong evidence against him at the early hearing, came into court she swore under oath that her earlier evidence had been false. She had lied to satisfy the police, that they had threatened her, if she refused, with taking her baby and her young sister into care. Despite the most aggressive attack from Mr Griffith Jones, and barely concealed hostility from the judge, she stuck to her story, that this was the truth and the earlier story she had told was lies." As Ricardo later told Anthony Summers: "Stephen was a good friend of mine. But Inspector Herbert was a good friend as well, so it was complicated."

Stephen Ward told his defence counsel, James Burge: "One of my great perils is that at least half a dozen of the (witnesses) are lying and their motives vary from malice to cupidity and fear... In the case of both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies there is absolutely no doubt that they are committed to stories which are already sold or could be sold to newspapers and that my conviction would free these newspapers to print stories which they would otherwise be quite unable to print (for libel reasons)."

Ward was very upset by the judge's summing-up that included the following: "If Stephen Ward was telling the truth in the witness box, there are in this city many witnesses of high estate and low who could have come and testified in support of his evidence." Several people present in the court claimed that Judge Archie Pellow Marshall was clearly biased against Ward. France Soir reported: "However impartial he tried to appear, Judge Marshall was betrayed by his voice."

That night Ward wrote to his friend, Noel Howard-Jones: "It is really more than I can stand - the horror, day after day at the court and in the streets. It is not only fear, it is a wish not to let them get me. I would rather get myself. I do hope I have not let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff but after Marshall's summing-up, I've given up all hope." Ward then took an overdose of sleeping tablets. He was in a coma when the jury reached their verdict of guilty of the charge of living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies on Wednesday 31st July. Three days later, Ward died in St Stephen's Hospital.

Ward's defence team found suicide notes addressed to Ronna Ricardo, Vickie Barrett, Mervyn Griffith-Jones, James Burge and Lord Denning: Barrett's letter to Barrett said: "I don't know what it was or who it was that made you do what you did. But if you have any decency left, you should tell the truth like Ronna Ricardo. You owe this not to me, but to everyone who may be treated like you or like me in the future."

Ludovic Kennedy commented: "Ricardo was clearly in a state of terror at what the police might do to her for having gone back on her original evidence. After the trial she seldom stayed at one address for more than a few nights for fear the police were looking for her."

Ricardo eventually travelled to the United States where she married her American airman lover, Silky Hawkins. In an interview she gave to Anthony Summers she claimed: "In Washington I was dragged into the offices of the CIA, and they said they knew all about me, from the cops in England." Ricardo was told that "her departure would be the best for all concerned."

Ricardo returned to London where she once again became a prostitute. She was interviewed by the authors of Honeytrap in 1987: "She has three children, all half-castes, and by different fathers. She is dramatically overweight, and by her own admission - is still on the game, on a part-time basis."

Primary Sources

(1) Ronna Ricardo, statement given to Scotland Yard (20th July, 1963)

I have come here this evening to make a statement about the Ward case. I want to say that most of the evidence I gave at Marylebone Court was untrue. I want to say I never met a man in Stephen Ward's flat except my friend 'Silky' Hawkins. He is the only man I have ever had intercourse with in Ward's flat.

It is true that I never paid Ward any money received from men with whom I have had intercourse. I have only been in Ward's flat once and that was with 'Silky'. Ward was there and Michelle. The statements which I have made to the police were untrue.

I made them because I did not want my young sister to go to a remand home or my baby taken away from me. Mr. Herbert told me they would take my sister away and take my baby if I didn't make the statements.

(2) Ludovic Kennedy, The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964)

What made the evidence of the prosecution at Ward's trial of such unflagging interest was the variety of the women who had been associated with him. The four on the bench could hardly have been more different: now a new star came to grace this milky cluster in the night sky. Her name was Margaret (Ronna) Ricardo and unlike Christine and Mandy she made no pretensions about not being a tart. It would be untrue to say she was not ashamed to admit it, for clearly she was ashamed or at least unhappy about it, but admit it she did. This honesty made a welcome change. She had dyed red hair and a pink jumper and a total lack of any sort of finesse; but after the genteel caperings of Christine and Mandy and the deadly respectability of Miss R, this also was welcome.

We had heard of Miss Ricardo before. She had given evidence at the Magistrate's Court proceedings three weeks earlier. There, among other things, she had said that she had visited Ward two or three times at his Bryanston Mews flat (we were on to Count 3 now) and on each occasion she was asked to stay behind to meet somebody. Men had arrived and she had gone to bed with them. Since then, however, she had gone to Scotland Yard to make a statement denying this. At the moment nobody knew for certain what she was going to say.

She took the oath and in answer to Mr. Griffith-Jones said that she had visited Ward at his flat in Bryanston Mews earlier this year. This, of course, was the flat where Rachman and Mandy had lived for two years. Ward had shown her the hole in the wall where the two-way mirror used to be and which Mandy in her evidence admitted to having broken. Miss Ricardo had said to Ward that she had had a two-way mirror herself. Ward had told her, she said, that he would "either cover the hole up or else get a new mirror", and she had said she had got an ordinary piece of mirror at home that would cover the gap. Now Mr. Griffith-Jones had said of the two-way mirror in his opening speech that when Ward moved into the Bryanston Mews flat "it was proposed to have it put in order again". This reply of Miss Ricardo's was the nearest he ever got to substantiating the assertion. The reader will have noticed that far from a categorical assertion of proposing to repair the mirror, Ward was undecided as to whether to cover the hole up or get a new mirror-a new mirror, note, nothing about a new two-way mirror. But how could the jury be expected to notice this?

.

(3) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Another prostitute who knew Ward was Ronna Ricardo. The police found her because one of her friends had a sketch by Ward on her wall. A police officer interviewing the friend on another matter noticed the sketch and inquired about it. The friend said she knew of Ward through Ricardo who had done business with Ward. Herbert and Burrows soon called on Ricardo. She was a tougher nut than Vickie Barrett and on one occasion when Sergeant Glasse interviewed her she lifted her skirt and pulled down her underwear to reveal on her stomach, written in large, indelible blue letters , the words ALL COPPERS ARE BASTARDS. She flatly refused to co-operate.

But the police persuaded her. Once more, this is the uncorroborated account of Ricardo herself, but again we believe her. She said a police car with two officers took up station outside her flat and was there for days on end, that this was intended to frighten her and that it succeeded. Then Herbert and Burrows interviewed her nine times and put tremendous pressure on her to say that when she had visited Ward at his Bryanston Mews flat Ward had asked her to stay behind to meet men and go to bed with them. Ricardo said that Herbert told her that if she did not agree to help them then the police would take action against her family. Her younger sister, on probation and living with her, would be taken into care. They might even make application to take her baby away from her because she had been an unfit mother. On the other hand, Herbert said, if Ricardo would help them by making a statement, she would not have to appear in court and she would be left alone. Both women had the feeling that the police were out to frame Ward and that they did not care how they did it.

(4) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

Two prostitutes were the main witnesses against him. One of them I knew, Ronna Ricardo. It was no secret that Stephen liked prostitutes, he felt superior to them and this was necessary to him, certainly in his sex life. There were many examples in his past life of girls he had met when they were young and new to London, and went to bed with. Like me, I suppose. But once they gained confidence and moved in his circle as an equal, he had no sexual interest in them, although he retained their friendship for years.

When Ronna Ricardo, who had provided strong evidence against him at the early hearing, came into court she swore under oath that her earlier evidence had been false. She had lied to satisfy the police, that they had threatened her, if she refused, with taking her baby and her young sister into care. Despite the most aggressive attack from Mr Griffith Jones, and barely concealed hostility from the judge, she stuck to her story, that this was the truth and the earlier story she had told was lies.

(5) Christine Keeler, The Truth at Last (2001)

One afternoon we went to Notting Hill and I didn't mind the daylight visit so much but I was still wary. We went to see Ronna Ricardo who had dark hair and almond-shaped, gullible eyes. She was a quiet-spoken, shy girl and I did not know then that she was a busy prostitute. One of her clients was a police detective called Samuel Herbert. Herbert committed suicide after playing a crucial role in all our lives. She had been to Cliveden, to the cottage, with Stephen. I don't know how she had figured in his plans but, later, she would turn on him. Then, we just had tea and she and Stephen talked quietly in the her small kitchen. I presumed she was just one of his girls, one he would call round to parade for him. I had no idea she would find her way into FBI files and be of interest to the American president. As I was to be.

(6) Anthony Summers, Honeytrap (1987)

That night, probably between seven and eight, Daily Express reporter Tom Mangold took a telephone call from Stephen Ward. Mangold had been covering the Profumo Affair for months. He was one of the few reporters Ward still trusted. Ward wrote in his memoir. The two men had spent night after night talking into the early hours. That night, Mangold was desperately tired. He also had personal problems, reaching crisis point, and this call was a damned nuisance. "He asked me to come around to where he was staying," says Mangold, now a Panorama reporter, and one of the most accomplished British journalists of our time. "He said it was urgent. I said I would come, but I didn't want to spend another long night talking."

Mangold drove to Mallord Street. He had been handling the prostitute Ronna Ricardo, as well as Ward. She had cried on his shoulder and told him, "I've fitted up Stephen." "There were two strands running through the thing, it seemed to me," Mangold says today. "There was some sort of intelligence connection, which I could not understand at the time. The other thing, the thing that was clear, was that Ward was being made a scapegoat for everyone else's sins. So that the public would excuse them. If the myth about Ward could be built up properly, the myth that he was a revolting fellow, a true pimp, then police would feel that other men, like Profumo and Astor, had been corrupted by him. But he wasn't a ponce. He was no more a pimp than hundreds of other men in London. But when the state wants to act against an individual, it can do it."

Tom Mangold knew Ward was at the end of his tether: "He felt absolutely betrayed. Until the very last minute he was certain that Lord Astor would turn up and pull him out of the shit. But he was abandoned. That night he asked me to post the letters he had written. I said I knew what they were, suicide notes, and I refused to post them for him." One of the letters was addressed to Mangold himself. "Well," Ward told the reporter, "take your letter, but don't open it till I'm dead."

Then Mangold left Ward, and went home. Today he is sad about what happened, but philosophical. A reporter must be compassionate, but cannot be held responsible for his interviewees. When the phone rang next morning with the news of Ward's suicide Mangold was not surprised.