George Wigg

George Wigg, the eldest of six children, was born in Ramsdell on 28th November, 1900. His father, Edward William Wigg, owned a dairy business. Wigg later recalled: "Whatever the reason, my father, easy-going, indolent, disgruntled and lacking ambition, failed at everything to which he turned his hand.... My mother, intelligent, hard-working and enterprising, did all the household chores, delivered the milk, served in the shop, kept the books and tried to inspire my father with the will to work.... My mother's immense vitality and drive - she bore six children at two-yearly intervals and slaved from early morning until late at night creating a home and keeping the business going - deserved success. My father's drinking habits frustrated all her toil and her hopes of saving her marriage."

Wigg won a scholarship when he was twelve to Queen Mary's Grammar School in Basingstoke. "Never did boy go more willingly to school than young Wigg to Queen Mary's Grammar School. Never was boy brought down to earth with a more sickening thud. The Headmaster was a clergyman. Nowadays he would be called a snob, but the epithet would be unfair and inadequate. He described me and other scholarship students at the school as 'boys for whose education your (the other boys') parents are paying'. He was a drinker who used the cane to cover up his own weaknesses of character. He blamed scholarship boys for every misdemeanour and belted them - and especially me - mercilessly. I handed the beltings on; my victims told their parents; the parents told the Head; and he belted me in what became a never ending process. I hated him and I hated the school, but I got quite a lot out of it. I acquired a smattering of languages and science, subjects not taught at Fairfields Council School. I shone in geography and history... I was wounded by the continual reference to the fact that my mother took in lodgers and that my books and fees were paid for by the parents of other boys."

The failure of his father's business meant that Wigg had to leave school at fourteen. He found a job at a timber merchants. He came under the influence of his foreman, Billy Drew, a Christian Socialist. "He was one of God's good men. While I worked under his guidance he instructed me in the principles of Socialism and explained the social value of the Co-operative and Trade Union Movements... I began to attend meetings under the Reformers' Tree, a hornbeam once standing beyond the last lamp in Brook Street, and a traditional place of assembly for dissenters, radicals and preachers of new and unpopular creeds."

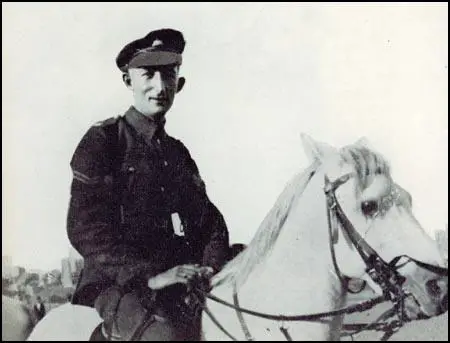

A few weeks before his seventeenth birthday, Wigg joined the 9th Battalion Hampshire Regiment at Hadiscoe. He was too young to fight in the First World War but on 3rd September, 1919, he was transferred to the Tank Corps. He was not too happy about being sent to break a railway strike: "I sympathized with the railwaymen's protest against wage reductions proposed by the Coalition Government. I did not share the official view that the strike was an anarchist conspiracy. I did not want to be associated with any Government-sponsored strike-breakers disguised as volunters for the job."

In 1920 Wigg was promoted to the rank of corporal and transferred to Aldershot. "I enjoyed the new life in Aldershot. The pay rise enabled me to increase the allotment to my mother and went a long way towards justifying my choice of career. Having gained a Second Class Certificate of Education while at Bovington, I was now studying for my First and, in addition, I joined English, history and science evening classes held at Aldershot Grammar School... Then came a dramatic change, promising the thrill of travel and thrusting me into the centre of world politics. I was posted to the British Forces of Occupation in Turkey." Wigg also served in Iraq, Palestine and Egypt.

Wigg continued his education by reading widely. Wigg thought that Old Soldiers Never Die by Frank Richards was the best book he had read on the First World War. He also impressed by Memoirs of an Unconventional Soldier by General John Fuller. Wigg also read a great deal about politics. This included books by George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, J. A. Hobson, G. D. H. Cole, Charles Kingsley, A. E. Housman, R. H. Tawney (The Acquisitive Society), Henry Noel Brailsford (The War of Steel and Gold: A Study of Armed Peace), Robert Cunninghame-Graham (How Capitalism Came to the Village) and Mark Rutherford (The Revolution in Tanner's Lane). Wigg later recalled that people everywhere were alive with what Robert Wilson Lynd, the radical journalist, described as "the passion of labour... to make the world a better place for the people who inhabit it."

On his return to England in 1931 he was based in Canterbury. He was active in the local Labour Party and took part in the 1931 General Election. Wigg also worked for the local Workers' Educational Association (WEA). During this period he became friends with A. D. Lindsay, master of Balliol College and Richard Sheppard, the founder of the Peace Pledge Union. "My mental turmoil in the early 1930s made me politically active." During this period he met Richard Crossman and Hugh Gaitskell. He was very impressed by Aneurin Bevan: "Nye Bevan became their star performer. A superb public speaker, Nye was master of any audience."

Wigg left the British Army in 1937 and worked full-time for the WEA. Woodrow Wyatt claims that "his belief in its virtues never faded, though he was prickly with authority when he thought it unjust... the social prejudices of the time unreasonably prevented his being a commissioned officer." Wigg became active in politics and joined the campaign against the government's policy of appeasement: "Action to prepare for armed resistance to Hitler and Mussolini was considered reprehensible. I developed a contempt for political pacifists and fence-sitters which I still feel. I have profound respect for the true pacifist and pray that in the long run he may prove to be right.... History holds the Men of Munich in derision. They were so determined to maintain the class structure of British society, which war must shake to its foundations, that they watched with equanimity the rise of Fascism in Spain, the re-armament of Germany in defiance of the Peace Treaties, Mussolini's assault on British Empire communications in his aggression against Abyssinia, and Germany's reentry into the Rhineland. Yet they were class war realists. Chamberlain's National Government put the lion's tail well and truly between its legs and convinced themselves, if and when the crunch came, that a people thus impoverished in spirit would slink away from battle."

On the outbreak of the Second World War he rejoined the army. Wigg became a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Army Education Corps. In 1943 he became the Labour Party candidate for Dudley and stood in the 1945 General Election. During the campaign several leading figures in the party, including J. B. Priestley, Harold Laski and Hugh Dalton: "I imagine that to every candidate in an election, win or lose, the result comes as a shock; the declaration of the poll produces the final tremor after a long period of suspense and nervous tension. I was as sure as every member of the magnificent team supporting me that I would win Dudley. Yet when victory came it was awesome and almost frightening.... The polling at Dudley was: George Wigg 15,439, Major E. Brinton, Con. 9,156; Labour majority 6,283."

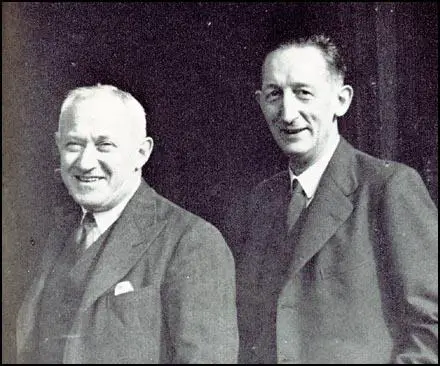

Soon after entering the House of Commons the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Wigg as parliamentary private secretary to Emanuel Shinwell as Minister of Fuel and Power (1945-47), Secretary of State for War (1947-50) and Minister of Defence (1950-51). His biographer, Woodrow Wyatt, has argued: "A man of swirling emotions prone to hero worship, Wigg attached himself passionately to Emanuel Shinwell."

After the 1951 General Election Wigg returned to the backbenches. According to his friend Arnold Goodman: "He (George Wigg) has massive faults. He is impatient; he is intolerant; he is quick tempered; he is merciless to those he regards as incompetent and ineffective if he believes they are taking rewards at the rate appropriate for competence and effectiveness, but he will get up in the middle of the night to bail out the son of some acquaintance charged with a minor offence and spend hours, days and weeks arranging the boy's future and seeking to redeem him from the consequences of some foolish indiscretion."

On 24th December 1962, John Lewis met Christine Keeler at a Christmas Party. Lewis found out from Keeler that she had been having a sexual relationship with John Profumo, the Minister of War and Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy. She also told him that she had been living with Stephen Ward and that he had introduced her to several famous people such as Profumo and Ivanov. Lewis realized that this provided him with a very good opportunity of gaining revenge on Ward as well as getting back into the House of Commons.

Lewis decided he would pass this information to George Wigg. The first meeting took place on 2nd January 1963. Wigg was interested in the story but asked Lewis to provide him with more information. Lewis now told Keeler he was willing to pay her £30,000 if her information brought the government down. Keeler responded by telling him that "Stephen (Ward) asked me to ask Jack Profumo what date the Germans were to get the bomb." Wigg's secretary remembers, "Mr Lewis constantly rang up during the day when Mr Wigg was about his parliamentary business. I frequently got the impression he wasn't completely sober. But he was insistent." On 7th January, Lewis told Wigg the story about Ward asking her to discover classified information from Profumo.

Wigg explained in his autobiography: "Lewis had attended a pre-Christmas party where a Miss Christine Keeler talked excitedly about a recent shooting incident, the first of several events destined to endow her with what she appeared to crave the reputation of being the most notorious woman in London. Miss Keeler, who said she had heard a Mr Stephen Ward refer to Lewis, asked if she could telephone him and, a few days later, sought his help. She then spoke about her friendship with John Profumo, Secretary of State for War, and with the Russian Naval Attaché, Captain Eugene Ivanov. Miss Keeler alleged that Ward had asked her to obtain from Profumo information about the supply of atomic weapons to the Germans... I rejected at once the idea that Profumo personally was a security risk. I had found him politically untrustworthy but I never regarded him as a fool, and I could not be persuaded that an obviously ignorant girl would be used as a go-between. It seemed to me the man to keep an eye on was Ivanov. Lewis agreed that the matter must be handled exclusively on the issue of security. I urged him to talk to the police and, at a later stage, advised him to talk to Commander Townsend at Scotland Yard. Lewis did talk to the police but, being dissatisfied with the results, returned to me again and again."

Warwick Charlton later explained. "John Lewis was an able politician. He had held pretty high office, but because of the way he was living he had lost his seat. He was desperate to get back in. He had two motives delivered to him by Christine: one, the Russian security thing, and, two, evidence that Stephen was a ponce. He'd have his revenge, and he had little presents to give Wigg to beat the Tory Party with, and he might get back and re-establish his reputation with Labour."

On 10th March, 1963, Wigg attended a party with Harold Wilson, the leader of the Labour Party, Richard Crossman and Barbara Castle. Crossman later recalled: "When we arrived at the party George outlined the story to us and we emphatically and unanimously repudiated it. We all felt that even if it was true and Profumo was having an affair with a call girl and that some Russian diplomat had been mixed up in it, the Labour Party simply should not touch it. I remember that we all advised Harold very strongly against it and in a way rather squashed George."

George Wigg got up in the House of Commons on 21st March and asked Home Secretary Henry Brooke, during a debate on the John Vassall affair: "I rightly use the Privilege of the House of Commons - that is what it is given me for - to ask the Home Secretary who is the senior member of the Government on the Treasury Bench now, to go to the Dispatch Box - he knows that the rumour to which I refer relates to Miss Christine Keeler and Miss Davies and a shooting by a West Indian - and, on behalf of the Government, categorically deny the truth of these rumours.... It is not good for a democratic State that rumours of this kind should spread and be inflated, and go on. Everyone knows what I am referring to, but up to now nobody has brought the matter into the open. I believe that the Vassall Tribunal need never have been set up had the nettle been firmly grasped much earlier on. We have lost some time and I plead with the Home Secretary to use that Dispatch Box to clear up all the mystery and speculation over this particular case." Richard Crossman then commented that Paris Match magazine intended to publish a full account of Keeler's relationship with John Profumo, the Minister of War, in the government. Barbara Castle also asked questions if Keeler's disappearance had anything to do with Profumo.

The following day John Profumo issued a statement: "I understand that in the debate on the Consolidated Fund Bill last night, under the protection of parliamentary privilege, the Hon. Gentlemen the Members for Dudley (George Wigg) ... spoke of rumours connecting a Minister with a Miss Keeler and a recent trial at the Central Criminal Court. It was alleged that people in high places might have been responsible for concealing information concerning the disappearance of a witness and the perversion of justice. I understand that my name has been connected with the rumours about the disappearance of Miss Keeler. I would like to take this opportunity of making a personal statement about these matters. I last saw Miss Keeler in December 1961, and I have not seen her since. I have no idea where she is now. Any suggestion that I was in any way connected with or responsible for her absence from the trial at the Old Bailey is wholly and completely untrue. My wife and I first met Miss Keeler at a house party in July 1961, at Cliveden. Among a number of people there was Doctor Stephen Ward whom we already knew slightly, and a Mr Ivanov, who was an attaché at the Russian Embassy.... Between July and December, 1961, I met Miss Keeler on about half a dozen occasions at Doctor Ward's flat, when I called to see him and his friends. Miss Keeler and, I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler."

When Harold Wilson became prime minister he appointed Wigg as his Paymaster General. According to his biographer, Woodrow Wyatt: "In 1964 he became paymaster-general with direct access to the prime minister on security and wider political matters. He was sworn of the privy council at the same time. Voluble in conspiratorial style, whether in person or on the telephone - frequently at unusual hours - he achieved a domination over Wilson which irritated colleagues including Marcia Williams, whose removal from the room he once successfully demanded when he wished to speak confidentially to the prime minister. Eventually Wilson was exhausted by Wigg's constant pummelling and in 1967 adroitly removed him from his presence by making him chairman of the Horserace Betting Levy Board with a seat in the House of Lords as a life peer. Though hipped at this loss of favour and subsequently ungracious about his patron, Wigg was also delighted. Wigg loved racing almost as much as he did the army and political intrigue, and was intermittently a keen owner of indifferent horses. He had been a member of the Racecourse Betting Control Board (1957–61) and of the Horserace Totalisator Board (1961–4)."

George Wigg died in London on 11th August 1983.

Primary Sources

(1) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

Whatever the reason, my father, easy-going, indolent, disgruntled and lacking ambition, failed at everything to which he turned his hand. My mother, intelligent, hard-working and enterprising, did all the household chores, delivered the milk, served in the shop, kept the books and tried to inspire my father with the will to work. She went to live on and off with my grandmother at The Villa, Ramsdell, near Basingstoke, and the process of to-ing and fro-ing between Ramsdale and Ealing continued until I was born. Hence I have a hunch that, although the birth was registered at Ealing, I was born at Ramsdell.

My mother's immense vitality and drive - she bore six children at two-yearly intervals and slaved from early morning until late at night creating a home and keeping the business going - deserved success. My father's drinking habits frustrated all her toil and her hopes of saving her marriage....

In modern times, I suppose, I would be dubbed the product of a broken home and the psychologists would find in that fact an explanation of my mental make-up and character. I think they would be wrong. Certainly, my father treated my mother badly. He shirked work. His contribution to the family income was negligible. Yet I cannot describe him as an utterly unsatisfactory father. His natural kindness, even his weaknesses, generated affection and gave me warning signs of some of the pitfalls in life I should try to avoid. When, at the age of ten, I accompanied him on the milk-round, sometimes cold as well as hungry and often feeling very sorry for myself, I vowed that when I grew up my children would not undergo such hardships. Years later I realized I could not seek the things I wanted for my children unless I sought and fought for them as the right of all children. That thought became an essential part of my Socialist faith.

There was another side to my father's weakness. His shortcomings highlighted my mother's qualities. No home over which she presided - and she presided all right! - could be described as "broken". Her personality inspired love and unity and the joy of living. She had dark brown eyes, framed in raven black hair. Her young beauty still haunts all my recollection of our wonderful life together. Yet her beauty was the least powerful quality of a compelling personality. She could dance and sing and pray, and she led the family in all these activities; and, when occasion demanded, she could swear. That a woman of such slight build could summon up so much vitality was, and remains, a source of amazement and inspiration to me.

(2) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

Never did boy go more willingly to school than young Wigg to Queen Mary's Grammar School. Never was boy brought down to earth with a more sickening thud. The Headmaster was a clergyman. Nowadays he would be called a snob, but the epithet would be unfair and inadequate. He described me and other scholarship students at the school as "boys for whose education your (the other boys') parents are paying". He was a drinker who used the cane to cover up his own weaknesses of character. He blamed scholarship boys for every misdemeanour and belted them - and especially me - mercilessly. I handed the beltings on; my victims told their parents; the parents told the Head; and he belted me in what became a never ending process. I hated him and I hated the school, but I got quite a lot out of it. I acquired a smattering of languages and science, subjects not taught at Fairfields Council School. I shone in geography and history, my star subjects under 'Buck' Lewis. I was wounded by the continual reference to the fact that my mother took in lodgers and that my books and fees were paid for by the parents of other boys.

(3) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

While I was at Woolwich, for the first and only time during my Army service, an officer showed interest in my welfare as a human being with hopes and ambitions. A Colonel Hanson inquired about my health and, after discussing my spare-time activities, suggested I should aim at something better than a low-grade clerical job. He advised me to go for a "Y" cadetship, something about which I had never even dreamed. I had taken Army First Class and Second Class Certificate of Education in my stride. I had attended evening classes in the hope of improving my general education. The idea of a commission from the ranks, however, was flying high indeed. Alas, these dreams were short-lived. My patron was ticked off, so he told me, for interesting himself in the affairs of other ranks. "I have landed you in trouble as well as myself," he explained, "but it is worse for you. The best advice I can give you is to get out of here." I had three more years to serve on my current engagement. Finances at home were not easy and the special Colonial allowances in Baghdad seemed attractive, so I volunteered for service in Mesopotamia, or Iraq, as it came to be called. By so doing I hoped to escape from a difficult situation and, at the same time, to increase the allotment to my mother from my pay. I attained both objectives.

(4) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

The Munich crisis precipitated a new ambivalence among my friends. Many of them wanted to stand up to Hitler, defend Czechoslovakia and Poland, and support Russian resistance to German Hitlerism. When I suggested we needed conscription and the reequipment of the armed forces with modern weapons, I was denounced as a "blimp".

Passing resolutions demanding action by the League of Nations met with enthusiastic support. Action to prepare for armed resistance to Hitler and Mussolini was considered reprehensible. I developed a contempt for political pacifists and fence-sitters which I still feel. I have profound respect for the true pacifist and pray that in the long run he may prove to be right. Among those I esteemed highly was the late Emrys Hughes who became a valued friend. Emrys was immensely more knowledgeable about defence matters than many who derided his pacifist beliefs.

History holds the Men of Munich in derision. They were so determined to maintain the class structure of British society, which war must shake to its foundations, that they watched with equanimity the rise of Fascism in Spain, the re-armament of Germany in defiance of the Peace Treaties, Mussolini's assault on British Empire communications in his aggression against Abyssinia, and Germany's reentry into the Rhineland. Yet they were class war realists. Chamberlain's National Government put the lion's tail well and truly between its legs and convinced themselves, if and when the crunch came, that a people thus impoverished in spirit would slink away from battle. And the Labour and Trade Union Movements were not blameless. Too few leaders faced the facts of the kind of world in which we lived. They under-estimated the limitations imposed on British power by our losses in World War I. The sacrifices aggravated by the incompetence and cowardice of politicians, through the years of uneasy peace, had destroyed national unity and divided Britain between "us" and "them". Fortunately, when the crunch did come, our people stood true to the British tradition of solidarity. This quality of mind and spirit ensured the survival of our country, and of democracy in the Western World.

(5) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

In the Autumn of 1942, the late Tom Wintringham suggested I should become organizer of Common Wealth, the new party led by Sir Richard Acland. Tom had contributed much to the development of Commando combat and Civil Defence training and he and I shared a common interest in military weapons and methods. He won distinction in the Spanish Civil War. By repudiating the Communist Party of which he had been a functionary, he demonstrated his strength of character. I respected the promoters of the Common Wealth Party although I doubted the wisdom of their approach. I held Sir Richard Acland in affection and admired his honesty of purpose. The late R. W. G. (Kim) Mackay, an Australian, was another Common Wealth leader whose drive impressed me. Aside from the personalities involved I felt there was a genuine need for a Party like Common Wealth to widen the Socialist appeal and bring to Labour's aid the intellectual qualities, panache and practical experience of affairs of Common Wealth's middle-class supporters. My doubts sprang from my working-class upbringing and ingrained loyalty to the Labour Movement.

These misgivings increased when J. B. Priestley resigned the Chairmanship of Common Wealth. Priestley's superb qualities as a writer flow from a love for and a belief in ordinary folk and, in the context of Common Wealth, a down-to-earth attitude to social and economic problems. Pressure on me increased and I sought advice from E. S. Cartwright. He, too, had interpreted Priestley's withdrawal as a sign that Common Wealth was failing to define clearly its purpose which, Cartwright thought, should be to create "a new Movement that would voice and genuinely attempt with all its strength to realize the aspirations of the great mass of workers in a way that conventional political Labour and the trade unions seem incapable of doing." Common Wealth, he feared, was too formless to satisfy my aspirations, but if I thought I could make Common Wealth an effective instrument of social change I should go right in. I decided to stick to the Labour Movement although I valued the work of Common Wealth in preparing the nation for social change.

(6) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

I imagine that to every candidate in an election, win or lose, the result comes as a shock; the declaration of the poll produces the final tremor after a long period of suspense and nervous tension. I was as sure as every member of the magnificent team supporting me that I would win Dudley. Yet when victory came it was awesome and almost frightening.

Dudley was included in the itinerary of Clement Attlee's General Election Tour. Labour's quiet-mannered leader, in a broadcast, had blown the larger-than-life Churchill and his assertion that Labour meant Gestapo rule right off the air. Dudley's reception of Attlee revealed how deeply the ordinary folk of Britain resented Churchill's impudent slanders. My other vote-compelling stars included J. B. Priestley, Harold Laski and Hugh Dalton. We had crowded halls and overflow meetings. The whole nation, like the Army under the impact of A.B.C.A., was listening, questioning and debating. The longer the Election lasted, the more certain, I felt, would be a Labour victory. Attlee shared my hope but not my view. The mood I caught in my talk with him was the possibility of stalemate. Certainly he, and Dalton too, thought another Election following the end of the Japanese War could be on the cards. The polling at Dudley was :

George Wigg 15,439, Major E. Brinton, Con. 9,156; Labour majority 6,283.

(7) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

Our discussions led to some M.P.s forming the Keep Left group. The famous Keep Left pamphlet was written by Michael Foot, R. H. S. Crossman and Ian Mikardo. They took responsibility for the detail and form of its arguments, with the whole group of concurring M.P.s sharing responsibility for its contents. We sought to define a modern philosophy for Labour and to represent, quite properly, the "politics of expectation". We drew heavily on the thinking of R. H. Tawney, A. D. Lindsay, William Temple and Harold Laski. Unfortunately, after the Party went into Opposition, "expectation" became a synonym for personal ambition. Some of the twenty or so Keep Left groupers were close friends of Bevan. I admired him and got on well with him. I thought his success at the Ministry of Health had earned him promotion to the Chancellorship of the Exchequer that went to Gaitskell. Bevan was passed over for two reasons. Attlee distrusted him and Morrison, who had not been a success as Foreign Secretary, would not agree to be out-distanced by any rival.

Bevan, despite wide knowledge and acute intelligence, failed to appreciate the political limitations of some of his friends. His career might have been even more distinguished if he had attached the importance it deserved to some of the political advice he was offered. He had one tremendous Parliamentary triumph about which I can testify personally. Churchill, in the 1951 Defence debate, knew that Labour policy was right but tried to split the pacifist Left from the Government and encompass the Government's defeat on a major issue, thus forcing a General Election. To the last we hoped the patriotism of the Shadow Cabinet expressed, according to our information, by Butler and Eden, would prevail over Churchill's opportunism. It did not. On the second day of the debate, February 15, Churchill moved this amendment: "That this House while supporting all measures conceived in the real interest of national security, has no confidence in the ability of His Majesty's present Ministers to carry out an effective and consistent defence policy in concert with their allies, having regard to their record of vacillation and delay."

I can recall no proposition more clearly intended to tickle the ears of the groundlings during my time in Parliament. It sought to denigrate defence from a national issue into a vulgar Party brawl. Bevan, Minister of Labour and National Service, replied for the Government. He asked me to brief him on the defence aspects. Throughout our long discussion and argument he took no notes. Yet he mastered the case completely and handed out devastating punishment to the Opposition. Several times he trapped Churchill into interruptions then smashed him into sullen silence. Churchill, Bevan teased, once the decoy of the Tory Party, had undergone a transformation; he had become their Jonah. Labour, Bevan went on, had brought into productive industry 1,800,000 men and women, who in 1939 had not been mobilized either for the Armed Services or for the civil economy. In the last three or four years we had made a greater contribution to defence than any country of comparable size. The Tory Party, like the Communist Party, was a century out of date; it was incapable of defending Social Democracy against dictatorship, Soviet or, indeed, any other kind. Bevan destroyed the amendment, supported by several hours of Tory oratory, in twenty triumphant minutes. I doubt if Hansard has ever reported so scintillating a success achieved in so short a space of Parliamentary time.

Bevan was a genius, but an undisciplined genius. How else could so able a man assume that no administrative change could be tolerated in the National Health Service? This, surely, was an aberration of genius in search of power. It is not practical politics to turn problems of social administration into issues of high principle, as Miss Jennie Lee was forced to agree when she discovered that the re-distributive policies of the 1966 Labour Government, and its pursuit of social justice, were more important than an increase in the price of prescriptions.

A matter of regret to me was that Bevan and Shinwell never hit it off together. Both were a credit to the working-class Movement. Neither had anything to fear from the political ambitions of the other. Shinwell was more steadfast and more reliable than Bevan and - dare I say it as his closest friend? - he chose his companions with more wisdom. Yet Bevan was a giant among men. A mighty tribune of Socialism, he also made a decisive mark on social legislation. If only he had kept clear of Lord Beaverbrook and, later, of the political pygmies who walked in his shadow, the Labour Movement might well have avoided the plight into which men of less vision led it.

(8) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

On November 11, 1962, I attended Armistice Services at Stourbridge and Dudley, then went for lunch to the home of our Labour Party Agent, Councillor Tommy Friend, where I found there had been a phone call for me. I telephoned my home in Stoke, but my wife had neither called me nor received a message. Soon afterwards the call to Friend's house was repeated. A muffled voice said, "Forget about the Vassall case. You want to look at Profumo." Then the phone went dead. Driving back to London, the nagging question kept recurring : how did the unknown caller know where I was, and how did he get the number? The incident came to mind repeatedly as the whispered scandal involving a Minister and a Russian diplomat gathered weight and pace. The first authentic information about the business was sent to me, unasked, by the late John Lewis, a Parliamentary colleague from 1945 until 1951, and it steadily developed into an intensely worrying security problem.

Lewis had attended a pre-Christmas party where a Miss Christine Keeler talked excitedly about a recent shooting incident, the first of several events destined to endow her with what she appeared to crave the reputation of being the most notorious woman in London. Miss Keeler, who said she had heard a Mr Stephen Ward refer to Lewis, asked if she could telephone him and, a few days later, sought his help. She then spoke about her friendship with John Profumo, Secretary of State for War, and with the Russian Naval Attaché, Captain Eugene Ivanov. Miss Keeler alleged that Ward had asked her to obtain from Profumo information about the supply of atomic weapons to the Germans although, according to Lewis's account, "she had never told this to Profumo". Lewis advised the lady to

consult a solicitor.I rejected at once the idea that Profumo personally was a security risk. I had found him politically untrustworthy but I never regarded him as a fool, and I could not be persuaded that an obviously ignorant girl would be used as a go-between. It seemed to me the man to keep an eye on was Ivanov. Lewis agreed that the matter must be handled exclusively on the issue of security. I urged him to talk to the police and, at a later stage, advised him to talk to Commander Townsend at Scotland Yard. Lewis did talk to the police but, being dissatisfied with the results, returned to me again and again.

I was faced now with one of the most difficult decisions of my political life. Never before had I raised an issue affecting a Minister without notifying that Minister of my intention in advance and, where appropriate, setting out the facts and arguments. The one occasion on which this principle of action had been exploited against me was by Profumo during the Kuwait debate. Should I now seek an interview with Profumo? Bearing in mind his conduct over Kuwait, could I trust him again? There was one alternative open to a Member of Parliament facing such circumstances and fearing, as I now feared, that security could be put at risk by Ivanov. That was to use Parliamentary privilege to expose the situation. This, Gaitskell had advised in our discussions about the Vassall case, is exactly what privilege is for.

I had not resolved my heart-and-mind searching when, on Sunday, March 10, I returned to London to attend a party at the home of Mrs Barbara Castle. Harold Wilson was there and we found a room in which to talk privately. I made the point that the situation was moving to a climax. The March 8 issue of Westminster Confidential, a small monthly newsletter, had summarized the stories which the girls - Miss Keeler had been joined by a Miss Mandy Rice Davies - were selling to newspapers. One of the points raised in the newsletter was, "Who was using the call-girl to "milk" whom of information - the War Secretary or the Soviet Military Attache? - ran in the minds of those primarily interested in security". I told Wilson there were rumours that the story was about to "break" in overseas newspapers and that two Sunday newspapers, expected to blow the gaff that morning, had not published a line of their boasted "scoops", although one of them, the Sunday Pictorial, had bought from Miss Keeler a story based on a letter addressed "Darling" and signed "J" - a signature with which I was familiar. I pointed out that the names of prominent persons were being associated with Christine Keeler and Dr Stephen Ward, a society portrait artist and osteopath, and that Captain Ivanov had left England hurriedly on January 29. I drew attention to the fact that Miss Keeler who, on December 14, 1962, had been shot up by a West Indian, John Edgecombe, jealous of her preference for another West Indian, "Lucky" Gordon, had gone abroad, although she was a vital witness in the trial, now pending, of Edgecombe.The time had come, I urged Wilson, to press the Government to make a statement. The opportunity might arise on the Service Estimates during the coming week that the Government should be urged to hold an inquiry, in private if it wished, and then make a statement in the House. We agreed that should a demand for an inquiry emerge, we would ask for a Select Committee with terms of reference to include the nature of the Prime Minister's responsibility for security.

Wilson's attitude indicated that he wanted to play it cool. He invited me to pursue the subject "on my own responsibility". I decided not to raise the matter in the House of Commons unless circumstances forced my hand. Should that happen, I must find a form of words neither libellous nor unfair, whether spoken in Parliament or outside it, and I sought the advice of Arnold Goodman.

On the night of Thursday, March 21, stories about pending revelations in the Foreign Press came to a head. The matter was in everyone's unspoken thoughts. Earlier in the day the late Ben Parkin had been pulled up by the bewildered Chairman of a Standing Committee when, speaking on the subject of London sewage, he had commented, "There is the case of the missing model. We understand that a model can quite easily be obtained for the convenience of a Minister of the Crown" - the reference being to a model provided by the Ministry of Transport to illustrate proposals for London traffic. It was also reported that Mrs Castle intended during the debate on the imprisoned journalists later that night, to raise the matter in the context of the "missing witness". So I decided to act. I rose at 11 p.m. to take part in the debate about the two journalists, Reginald Foster and Brendan Mulholland, who had been committed to prison for refusing to disclose their sources of information to the Radcliffe Tribunal on the Vassall case.

(9) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972)

On Tuesday, March 26, around 5 p.m. I was handed a telephone message by a House of Commons official, asking me to ring Stephen Ward at a Paddington number... I rang Ward from the one telephone to which an earpiece was attached to the ordinary receiver so that Wilfred Sendall, the distinguished political journalist who was with me when I received Ward's message, could take a note of the conversation. Ward, it appeared, had been agitated by my comment in a television programme the previous evening that the real issue involved was security. He rambled on about persons and places. I cut him short with an intimation that I was not interested in private lives, but if he wanted to talk about security I would meet him in the Central Lobby at 6 p.m. Sendall witnessed his arrival.

Immediately after Ward left the House at 9 p.m. I told Harold Wilson that my visitor claimed to have written both to him and to the Prime Minister towards the end of the Cuban crisis. The letter was immediately extracted from the files and Wilson at once recalled a phrase about an approach made by Ward on behalf of Ivanov to the Foreign Office: "I was the intermediary", Ward had written. Next day, Wilson handed Ward's letter to the Prime Minister and expressed his now acute anxiety about the implication that Ward was a contact between Ivanov and people of influence in this country. I recorded my conversation with Ward which I showed to Wilson, who asked me to prepare an appreciation for his information. I completed this task on March 29. Wilson also asked the Chief Whip, Bert Bowden, to seek Sir Frank Soskice's advice. When Wilson returned home from his visit to the late President John Kennedy the same old questions rose again: was there a prima facie case for an Inquiry and, if so, what form should it take and how should the Opposition seek to obtain it? Soskice (now Lord Stow Hill) thought there was a clear case for further action based on my appreciation. With Bowden agreeing, the document was handed to the Government Chief Whip together with a covering letter, dated April 9, from Wilson addressed to the Prime Minister.

The following is a summary prepared from the document sent to the Prime Minister, especial care having been taken to record Ward's statements with absolute accuracy.

On our way to the Harcourt Room, Ward chatted about his familiarity with the House of Commons, to which he had often brought Ivanov, and about his contacts with Members and Conservative Ministers. He was anxious I should know the truth about Ivanov and the circumstances in which he had met him. Then the sight of an ex-Minister seemed to unnerve him. "He must not see me with you," he exclaimed. "I must leave at once. I ought not to have come here, I know too many people. I must leave at once." I took him to a private interview room and we started our talk afresh.

Ward said he first met Ivanov some time in 1961 at a Garrick Club lunch where, with a journalist specializing in Soviet affairs, they were guests of a Fleet Street editor. Ward found Ivanov a charming man. He taught him to play bridge and, soon, was seeing him two or three times a fortnight. They had fun with girls, although nothing improper ever took place, and they played bridge. They had visited only one night club, The Satyr, together, and then only for ten minutes. Ward said Ivanov never spoke critically about the British people. His one desire, which Ward shared, was to foster Anglo-Soviet friendship. Ward said he last saw Ivanov shortly before Christmas.

The Security Service, Ward asserted, knew all about his association with Ivanov. Representatives of the Security Service had enquired about his various meetings and Ward had promised to keep them informed and had kept that promise. He cited two occasions on which he thought friendship with Ivanov had been of value to Britain. At the time of the Berlin crisis in 1962 he, acting for Ivanov, had informed Sir Harold Caccia and other Foreign Office officials that the Soviet Union would adopt a conciliatory policy in return for Western guarantees about the integrity of the Oder-Neisse Line. I pressed him hard at this point, enquiring if he personally saw Sir Harold or other Foreign Office officials. He was not prepared to say; many important people, including Conservative M.P.s, were involved in the business.

His second venture in Ivanov - directed diplomacy - again as a go between - occurred during the Cuban crisis. This time, according to Ward, he was the link between Ivanov as peacemaker and the British Government, represented by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Home, and the Prime Minister. Ivanov told Ward the Russians would respond to a British initiative calling a conference in London by halting the delivery of arms and stopping all shipments of war equipment to Cuba. I pressed even harder on this subject for the obvious reason that I did not believe that Ward, personally, had been in touch with the Foreign Secretary and the Prime Minister Ward became cagey again. He was not prepared to say because too many important people were involved.

Having, as he thought, achieved his purpose of clearing himself as a security risk, Ward talked freely about his relations with Profumo whom he and Christine Keeler had met at Cliveden. A photograph of Profumo and the girl swimming there, he alleged, had been stolen recently from his flat. Profumo had visited Ward's flat at least six times. The Security Service knew all about these visits for Ward kept them informed.

Ward went on to say that about three weeks before the trial of Edgecombe opened Christine Keeler and Paul Mann had become aware of the cash value of letters Profumo had written to the girl brief notes signed "J", expressing regret for not meeting or making further assignations. Ward could have them for five thousand pounds. Otherwise they would go to the highest bidder. Mann was already seeking contact, Ward said, with the Manchester office of the Sunday Pictorial. Ward said that in a disinterested endeavour to protect Profumo, he arranged a meeting with him at the Dorchester Hotel where, according to his story, Profumo's reaction was that he could not remember the girl. Ward advised him to assist his memory by consulting the Security Service. They would be able to help for they had the data, including dates, which he, Ward, had supplied to them.

Ward next turned to his own relations with the Press. Christine Keeler had received two advances on account amounting to two hundred and fifty pounds from the Sunday Pictorial. In addition she had been installed in a flat at Park West by that newspaper. Learning that publication was imminent, Ward approached the Sunday Pictorial, challenged Miss Keeler's veracity, and made a deal resulting in the publication of his own story and the suppression of Miss Keeler's version. For that deal, he alleged, he received only a contribution towards his legal costs. An enraged Paul Mann then took the Christine Keeler story to the News of the World. Ward claimed he also intervened with that newspaper by providing material for an article which appeared simultaneously with his Sunday Pictorial story. Ward also referred to the activities of a person named Barratt or Bell who, citing Ward as his source, had sold stories to the Express newspapers and to the People.

Ward's narrative now moved on to the life of Christine Keeler and her friend Mandy Rice Davies in the Park West flat. "Lucky" Gordon, the Negro slashed by Edgecombe, joined her there. So did his wife and family. Miss Keeler's relations with coloured men had always been a matter of deep concern to Ward. She had lived in lodgings with Edgecombe at Ealing. While there she bought a gun from a criminal Negro involved in what Ward called the "Queen's Park hold-up", and this was the gun with which Edgecombe had fired shots into Ward's flat. After leaving Ealing with her landlord's son, Miss Keeler lived with both Edgecombe and `Lucky' Gordon thus arousing the jealousies which provoked the knife slashings and the shootings directed by these men against Miss Keeler and against each other. All four actors in the drama - Miss Keeler, Miss Davies, and the two West Indians - were reefer smokers; all, Ward said sadly, were utterly unstable and unpredictable.

I questioned Ward closely about what exactly Christine Keeler and her new friend, Paul Mann, were offering for sale. Ward was positive that Mann had taken the photograph of Profumo and the girl, and he suspected that Mann also held the Profumo letters. He was certain Mann had not approached Profumo, but he was convinced Profumo had spoken to Miss Keeler by telephone. He was equally convinced Profumo had not compromised State security in any way and no security risk had arisen through Profumo's contact with Ivanov and Christine Keeler or through the girl's contact with Ivanov. He asserted that his practice as an osteopath was being ruined, the Press were pursuing him on all sorts of charges, and he had got nothing out of his efforts to protect Profumo's reputation. Yet Paul Mann and Christine Keeler had obtained considerable sums of money which rightfully should have been his. On top of all this he was worried by my television statement that security was the sole consideration. He had come to convince me that, on this aspect of the case, he was in the clear....

The essential facts, in my opinion, were these: Profumo was not, at any time, a security risk. The Security Service knew all about his meetings with Ivanov and Miss Keeler and about Ward's friendship with Ivanov. Ivanov's friendship with Ward enabled him to move freely in Ward's own wide and ever growing circle of acquaintances.

(10) Stephen Ward, letter sent to Henry Brooke, Harold Wilson and William Wavell Wakefield (19th May, 1963)

I have placed before the Home Secretary certain facts of the relationship between Miss Keeler and Mr Profumo since it is obvious now that my efforts to conceal these facts in the interests of Mr Profumo and the Government have made it appear that I myself have something to hide - which I have not. The result has been that I have been persecuted in a variety of ways, causing damage not only to myself but to my friends and patients-a state of affairs which I propose to tolerate no longer.

(11) George Wigg, speech, House of Commons (21st March, 1963)

I rightly use the Privilege of the House of Commons - that is what it is given me for - to ask the Home Secretary who is the senior member of the Government on the Treasury Bench now, to go to the Dispatch Box - he knows that the rumour to which I refer relates to Miss Christine Keeler and Miss Davies and a shooting by a West Indian - and, on behalf of the Government, categorically deny the truth of these rumours.

On the other hand, if there is anything in them, I urge him to ask the Prime Minister to do what was not done in the Vassall case-set up a Select Committee so that these things can be dissipated, and the honour of the Minister concerned freed from the imputation and innuendos that are being spread at the present time.

It is not good for a democratic State that rumours of this kind should spread and be inflated, and go on. Everyone knows what I am referring to, but up to now nobody has brought the matter into the open. I believe that the Vassall Tribunal need never have been set up had the nettle been firmly grasped much earlier on. We have lost some time and I plead with the Home Secretary to use that Dispatch Box to clear up all the mystery and speculation over this particular case.