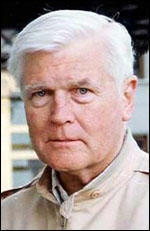

Tennent Bagley

Tennent Harrington Bagley, the son of a vice-admiral, was born in Annapolis, Maryland, on 11th November, 1925. His mother began calling him “Pete” when he was a child and this became his accepted name. (1)

Bagley's great uncle, Admiral William D. Leahy, later served as Chief of Staff to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. (2)

As a young man, he accompanied his father on naval assignments around the United States and around the world.

During the Second World War he served in the United States Marines. After the war Bagley studied political science from the University of Southern California. He graduated in 1947 and then obtained a doctorate at the University of Geneva. (3)

Tennent Bagley - CIA

Bagley joined the Central Intelligence Agency in 1950 and worked in Vienna for four years and in 1954 escorted Soviet defector, Peter Deriabin, back to Washington. Bagley was then transferred to Geneva. In 1961 he was put in contact with Yuri Nosenko, a member of the Soviet delegation to disarmament talks. He revealed that he served in the Far East and specialized in the recruitment of tourists in Tokyo and other cities. Nosenko also told Bagley about listening devices at the US embassy in Moscow, and confirmed the identities of British Admiralty clerk John Vassall, the Canadian ambassador John Watkins and the CIA agent Edward Ellis Smith, all compromised in KGB "honeytrap" stings". (4)

Some of this information had been revealed by an earlier defector, Anatoli Golitsin. But Nosenko denied Golitsin's claim of another Soviet mole higher up in the Admiralty, and refused to defect on the grounds he would not leave his wife and children behind. Golitsyn had been interviewed by James Jesus Angleton. A fellow officer, Clare Edward Petty, later recalled: "With the single exception of Golitsyn, Angleton was inclined to assume that any defector or operational asset in place was controlled by the KGB." Angleton and his staff began debriefing Golitsyn. He told Angleton: "Your CIA has been the subject of continuous penetration... A contact agent who served in Germany was the major recruiter. His code name was SASHA. He served in Berlin... He was responsible for many agents being taken by the KGB." (5)

In these interviews Golitsyn argued that as the KGB would be so concerned about his defection, they would attempt to convince the CIA that the information he was giving them would be completely unreliable. He predicted that the KGB would send false defectors with information that contradicted what he was saying. The CIA were now uncertain whether to believe Golitsin or Nosenko.

Yuri Nosenko

In January 1964 Yuri Nosenko contacted the CIA and said he had changed his mind and was now willing to defect to the United States. He claimed that he had been recalled to Moscow to be interrogated. Nosenko feared that the KGB had discovered he was a double-agent and once back in the Soviet Union would be executed. He claimed that he had been put in charge of the KGB investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald. He denied the Oswald had any connection with KGB. After interviewing Oswald it was decided that he was not intelligent enough to work as a KGB agent. They were also concerned that he was "too mentally unstable" to be of any use to them. Nosenko added that the KGB had never questioned Oswald about information he had acquired while a member of the U.S. Marines. This surprised the CIA as Oswald had worked as a Aviation Electronics Operator at the Atsugi Air Base in Japan. (6)

Richard Helms, the CIA's Deputy Director of Plans, was not convinced that Yuri Nosenko was telling the truth: "Since Nosenko was in the agency's hands this became one of the most difficult issues to face that the agency had ever faced. Here a President of the United States had been murdered and a man had come from the Soviet Union, an acknowledged Soviet intelligence officer, and said his service had never been in touch with Oswald and knew nothing about him. This strained credulity at the time. It strains it to this day." (7)

Evan Thomas, the author of The Very Best Men (1995), points out that James Jesus Angleton also did not believe Nosenko. "Angleton never got over suspecting that the Russians or Cubans plotted to kill Kennedy. He thought that the Russians or Cubans plotted to kill Kennedy. He thought the Russian defector, Yuri Nosenko, who claimed that the Kremlin was innocent, was a KGB plant to throw the CIA off the trail. But most reputable students of the Kennedy assassination have concluded that Khrushchev and Castro did not kill Kennedy, if only because neither man wanted to start World War III." (8)

Anatoli Golitsin provided information that supported Angleton's view. He had worked in some of the same departments as Nosenko but had never met him. After being interviewed for several days Nosenko admitted that some aspects of his story were not true. For example, Nosenko had previously said he was a lieutenant colonel in the KGB. Nosenko confessed that he had exaggerated his rank to make himself attractive to the CIA. However, initially he had provided KGB documents that said Nosenko was a lieutenant colonel. (9)

J. Edgar Hoover welcomed the information from Nosenko: "Nosenko's assurances that Yekaterina Furtseva herself had stopped the KGB from recruiting Oswald gave Hoover the evidence he needed to clear the Soviets of complicity in the Kennedy murder - and, even more from Hoover's point of view, clear the FBI of gross negligence. Hoover took this raw, unverified, and untested intelligence and leaked it to members of the Warren Commission and to President Johnson." (10) Hoover leaked this information to the Warren Commission. This pleased its members as it helped to confirm the idea that Oswald had acted alone and was not part of a Soviet conspiracy to kill John F. Kennedy.

Despite the fact that the Warren Commission received information from Hoover about Yuri Nosenko his name is not mentioned in the final report. Although the commission favoured Hoover’s interpretation that he was a genuine defector, it was decided that it was better not to include the information. This was decided after Tennent Bagley, spoke to commission members on 24th July, 1964: “Nosenko is a KGB plant and may be publicly exposed as such some time after the appearance of the Commission’s report. Once Nosenko is exposed as a KGB plant, there will arise the danger that his information will be mirror-read by the press and public, leading to conclusions that the USSR did direct the assassination.” (11)

James Jesus Angleton

James Jesus Angleton, the head of the CIA's counter-intelligence unit, became convinced that a senior figure in the CIA was a Soviet mole. In 1966 he instructed Clare Edward Petty, of the Special Investigations Group (SIG) to investigate the claims made by Anatoli Golitsin. Angleton suggested that Petty should take a close look at David Edmund Murphy. Golitsin suggested that Murphy might have been recruited as a spy when working in Berlin in the 1950s. Angleton's suspicions were increased by Murphy speaking fluent Russian and marrying a woman who had previously lived in the Soviet Union. (12)

Petty investigated Murphy's wife and found that her family had fled from Russia after the Russian Revolution. They moved to China before settling in San Francisco. Petty could find no evidence that she was pro-communist. Newton S. Miler, a member of SIG had investigated Murphy in the early 1960s. He discovered that a large number of his operations had been unsuccessful: "Just a series of failures, things that blew up in his face. Odd things that happened. The scrapes in Japan and Vienna. They (the KGB) may have been setting up Murphy just to embarrass CIA. But you have to consider these incidents may have been staged to give him bona fides." (13) Petty came to the conclusion that Murphy was "accident prone".

Petty eventually produced a twenty-five-page report that concluded that there was a "probability" that Murphy was innocent. Petty felt that Murphy may have been targeted by the KGB, but was never recruited. (14) However, Angleton rejected the report as he was convinced he was a spy. In 1968 Angleton arranged for Murphy to be removed from his job as head of the Soviet Division and assigned to Paris as station chief. Angleton then contacted the head of French intelligence and warned him that Murphy was a Soviet agent. (15)

James Jesus Angleton now asked Clare Edward Petty to investigate Tennent Bagley. This was a surprising suggestion as Bagley had always been a loyal supporter of Angleton. However, Angleton believed that Bagley had deliberately mishandled the attempted recruitment of a minor Polish intelligence officer in Switzerland. "Petty fastened on an episode that had taken place years earlier, when Bagley had been stationed in Bern, handling Soviet operations in the Swiss capital. At the time, Bagley was attempting to recruit an officer of the UB, the Polish intelligence service, in Switzerland. Petty concluded that a phrase in a letter from Michal Goleniewski, the Polish intelligence officer who called himself Sniper... the KGB had advance knowledge that could only have come from a mole in the CIA." (16)

Petty spent a year investigating Bagley, who had remained one of Angleton's strongest supporters. Petty's 250 page report on Bagley concluded that he "was a candidate to whom we should pay serious attention". However, Angleton rejected the report and told Petty: "Pete's not a KGB agent, he's not a Soviet spy." As Tom Mangold, the author of Cold Warrior: James Jesus Angleton: The CIA's Master Spy Hunter (1991) has pointed out: "A lesser man than Petty might have given up at this stage. He had investigated, on his master's behalf, a former chief and deputy chief of the Soviet Division - incredible targets in themselves - and had failed to prove either case. But Petty remained convinced that a mole existed." (17)

During the investigation Bagley became CIA station chief in Belgium. He held the post until he stepped down in 1972. In his retirement he wrote books about the KGB. In 1990, with former Soviet agent Peter Deriabin, he published KGB: Masters of the Soviet Union. This was followed by his autobiography, Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries, and Deadly Games (2007) that dealt in detail with the case of Yuri Nosenko. One reviewer, David Ignatius wrote: “It’s impossible to read this book without developing doubts about Nosenko’s bona fides. Many readers will conclude that Angleton was right all along - that Nosenko was a phony, sent by the KGB to deceive a gullible CIA.” A third book, Spymaster: Startling Cold War Revelations of a Soviet KGB Chief, was published in 2013 and recounted the experiences of Sergei A. Kondrashev. (18)

Tennent Harrington Bagley died on 20th February, 2014, at his home in Brussels.

Primary Sources

(1) Evan Thomas, The Very Best Men: The Early Years of the CIA (1995)

CIA headquarters at Langley was in a state of chaos when FitzGerald and Halpern arrived back from the City Tavern Club on Friday afternoon. "We all went to battle stations," recalled Richard Helms. "Was this a plot? Who was pulling the strings? And who was next?" In the basement vault occupied by the Special Affairs Staff, "all kinds of theories popped up," said Halpern. "Was it Castro? We had no intelligence. We didn't think Castro was that crazy. We thought maybe it had to do with KGB "wet affairs's" - abotage and assassination.

When Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested early that afternoon, the CIA began to piece his background, which was worrisome. He had defected to the Soviet Union in 1959 and then redefected back to the United States in 1962. More recently, in September, he had been spotted by CIA cameras entering the Soviet embassy in Mexico City, ostensibly to get a visa. While there, Oswald had been interviewed by a KGB agent, Valery Kostikov. This was a startling discovery. Kostikov was a member of the KGB's 13th Department, which handled "wet affairs." The deputy chief of thc. CIA's Soviet Division, T. H. Bagley, immediately saw the sinister implications. "Putting it baldly," he wrote to his superiors on Saturday, November 23, "was Oswald, wittingly or unwittingly, part of a plot to murder President Kennedy in Dallas?" The CIA's counter-intelligence staff began working around the clock to see whom else Kostikov had been talking to in his Mexico City lair.

(2) Mark Riebling, Wedge: From Pearl Harbor to 9/11 (1994)

On June 5, 1962, Yuri Nosenko, a KGB security officer with the Soviet Disarmament Commission, approached an American diplomat at U.S.-Soviet disarmament talks in Geneva, Switzerland, and whispered that he wished to talk privately with U.S. intelligence. He was met in a safehouse by CIA officer Tennent H. "Pete" Bagley. After offering Nosenko some liquor and peanuts, Bagley said he would appreciate the Soviet's speaking clearly and slowly, and in English wherever possible. Nosenko then delivered a great number,of sentences, fast, in Russian, while swigging whiskey and munching nuts. Because of the language problem, Baghad had to puzzle out much of what Nosenko said from a tape of the conversation, which had been made automatically by a recorder in the wall but even then there were gaps. In the early 1960s, portable tape recorders were not the refined machines they later became, and there was much ambient noise. The machine would pick up the crumpling of paper, the scraping of a match, the drone of a distant airplane, yet fail to record key words or phrases. The essence of Nosenko's message, however was clear: he was in financial trouble, and would work for CIA as an agent-in-place. To prove his sincerity, he would tell what he knew about KGB penetration of CIA. After hearing him out, Bagley cabled headquarters that Nosenko had "conclusively proven his bona fides."

But when Bagley flew home that weekend to make a full report, Angleton was skeptical. All of Nosenko's information was of the "throw away variety, the CI chief said. Nosenko spoke of Department D, but ; after Golitsyn had already disclosed it. Nosenko gave specific locations of microphones at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, but Golitsyn had provided approximate locations of some of the microphones six months earlier. Nosenko also said that Pytor Popov had been detected in 1959 by a special KGB "spy dust" sprayed on the shoes of his Western contacts, not blown by a mole in CIA, and that "Sasha" was a low-ranking Army officer, a high-ranking Agency man. Might not Nosenko be a false defector, intended to throw CIA off the trail of its mole(s)?

Bagley eventually bought that logic. He wondered what disinformation Nosenko would try to feed CIA when he next made contact, as he promised to to do whenever he was outside the Soviet bloc. Thanks to Golitsyn, CIA was "keyed in" to an apparent KGB deception game right from the start.

(3) David Wise, Molehunt (1992)

Tennent Harrington "Pete" Bagley had arrived in Switzerland by a more conventional route. Bagley was handsome, cultivated, buttoned down, and ambitious, with a quick, analytical mind and social and family credentials rooted in the Navy and Princeton. Then thirty-six, he had been born in Annapolis, the son of a vice-admiral. Two brothers also became admirals, one serving as vice-chief of naval operations, the other as commander of U.S. naval forces in Europe. His great-uncle Admiral William D. Leahy had served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt's wartime chief of staff.

Instead of following family tradition, Bagley joined the Marines on his seventeenth birthday in 1942. After the war, he attended Princeton, but he got his bachelor's degree at the University of Southern California, and a doctorate in political science at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. He joined the CIA in 1950, worked in Vienna for four years in the early fifties-that was when he escorted Soviet defector Peter Deriabin back to Washington-and was near the end of a four year tour in Bern, where he had handled the Goleniewski letters, when Nosenko made contact in Geneva.

Kisevalter and Bagley did not have to wait very long. "About two days after I arrived in Geneva," Kisevalter said, "Nosenko walks in one afternoon. He's in his thirties, nice-looking, brown hair, about five-ten, fairly muscular. He's very nervous, and starts drinking."The KGB man offered to sell information to the CIA for 900 Swiss francs, claiming he needed the money to replace KGB funds he had spent on a drinking bout. Later, Nosenko admitted he invented this story; he said he feared that an offer to give away information for nothing would be rejected as a provocation, as had sometimes happened in the past when KGB officers, acting under instructions, approached the CIA.

(4) Emily Langer, Washington Post (24th February, 2014)

Tennent H. “Pete” Bagley, a former CIA officer who led the agency’s counterintelligence activities against the Soviets during a tense period of the Cold War and played a key role in the controversial handling of Soviet defector Yuri Nosenko, died Feb. 20 at his home in Brussels. He was 88. The cause was cancer, said his son, Andrew Bagley.

Dr. Bagley, the son and brother of Navy admirals, joined the fledgling Central Intelligence Agency in 1950. An intellectual fluent in several languages, he rose quickly, ascending by the 1960s to serve as deputy chief of the Soviet bloc division, and was specifically tasked with countering the activities of the KGB.

At the time, the agency’s counterintelligence efforts came under the direction of James J. Angleton, the CIA official who became a divisive figure for his passionate pursuit of Soviet “moles” or infiltrators, who he believed were undermining the agency from within. In 1974, under CIA Director William E. Colby, Angleton surrendered his post.

Dr. Bagley embarked on what would become his most noted work in 1962, when, at a Geneva safe house, he met KGB agent Yuri Ivanovich Nosenko. Nosenko would become one of the most controversial figures in the history of U.S. counterintelligence, and Dr. Bagley was described as his chief handler.

In time, according to published reports, Nosenko disclosed to his U.S. interlocutors key information about Soviet infiltration of Western embassies and about his country’s intelligence-gathering practices.

Regarded as more impressive were Nosenko’s later revelations about Lee Harvey Oswald, whom Nosenko said he had interviewed during Oswald’s stay in the Soviet Union in the years before the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Nosenko told CIA officers that Oswald had no connection with the KGB - a significant assertion at a time when many officials feared that the assassination could be linked to the Soviets.

During the long period of Nosenko’s debriefing, some in the CIA - including Dr. Bagley and Angleton - noted significant inconsistencies in the information that he provided and concluded that he was not a real defector but rather a “plant” employed by the Soviets.

When Nosenko came to the United States in 1964, he was subjected to what The Washington Post called a “three-year harsh detention and hostile interrogation” including “body searches, verbal taunts, revolting food and denial of such basics as toothpaste and reading materials.” Dr. Bagley maintained that the interrogation did not include torture.

He prepared what were described as 900 pages of material about Nosenko. The report noted that Nosenko never “broke” under interrogation, The Post reported. Despite this, the report offered what was described as extensive circumstantial evidence that he was indeed a plant.

Nosenko passed numerous lie-detector tests, and the CIA determined in 1969 that he had been a genuine defector. The agency later employed him as a consultant. He died in 2008 in an undisclosed location in the United States.

In 1967, Dr. Bagley became CIA station chief in Brussels. He held the post until he stepped down in 1972. After a second career as a consultant, he pursued a third career, writing books.

In 1990, with former Soviet agent Peter Deriabin, he published KGB: Masters of the Soviet Union. In 2007, he published the memoir Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries, and Deadly Games.

“It is a stunner,” David Ignatius wrote in The Post of the 2007 book. “It’s impossible to read this book without developing doubts about Nosenko’s bona fides. Many readers will conclude that Angleton was right all along - that Nosenko was a phony, sent by the KGB to deceive a gullible CIA.”

In the New York Times, reviewer Evan Thomas wrote of “Spy Wars” that “though many intelligence old-timers will not be persuaded, Bagley offers a provocative new look at one of the great unresolved mysteries of the Cold War.”

A third book, Spymaster: Startling Cold War Revelations of a Soviet KGB Chief, was published in 2013 and recounted the experiences of Sergey Kondrashev. Like Dr. Bagley’s previous books, it included extensive interviews with his former foes, some of whom he traveled to Eastern Europe to meet. Former Wall Street Journal reporter Frederick Kempe accompanied Dr. Bagley on some of those meetings.

“It’s sort of like two soccer coaches of championship teams getting together and recounting their matches,” he recalled in an interview.

Tennent Harrington Bagley - his mother began calling him “Pete” when he was a child - was born on Nov. 11, 1925, in Annapolis. As a young man, he accompanied his father on naval assignments around the United States and around the world.

After Marine Corps service in World War II, Pete Bagley received a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Southern California in 1947 and, later, a doctorate in political science from the Graduate Institute in Geneva. In the early years of his CIA career, he served in Vienna, where he married Maria Lonyay, his wife of 58 years.

Besides his wife, who lives in Brussels, survivors include three children, Andrew Bagley of Columbia, Md., Christina Bagley Rocca of Arlington and Patricia Bagley of Reston; a brother; and five grandchildren.

Dr. Bagley once described the essential difficulty of counterintelligence. “It takes a mole,” he told the New York Times, “to catch a mole.”