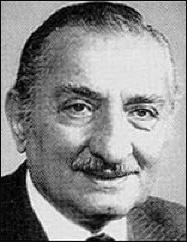

George Kalaris

George Kalaris, the son of Greek immigrants, was born in Billings, Montana, in 1922. His parents owned restaurants in the town. (1)

Kalaris worked as a lawyer in the Labor Department before he joined the Central Intelligence Agency in 1952. (2) According to David Binder "Kalaris had spent most of his career as a clandestine operations officer in Greece, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines and Brazil." (3)

In July 1973, William Colby was appointed as the new Director of the CIA. Colby soon clashed with James Jesus Angleton, the CIA chief of counter-intelligence: "Colby had long believed that the true function of the agency was to collect and analyze information for the President and his policymakers. He maintained that it was not the CIA's function to fight the KGB; the KGB was merely an obstacle en route to scaling the walls surrounding the Politburo and the Central Committee. In Colby's mind, his concept of the CIA's mission was an article of faith. But in Angleton he saw only a KGB fighter and a failed spycatcher." (4)

James Jesus Angleton

Colby told David Wise that he feared that Angleton would commit suicide if he was removed from his post. He therefore decided to gradually ease him out. He took away Angleton's control over proposed clandestine operations. This was followed by removing his power to review operations already in progress. As each of these roles were removed, the size of Angleton's staff dwindled from hundreds to some forty people. However, Angleton refused to resign: "Taking away FBI liaison and the other units was designed to lead him to see the handwriting on the wall. He just wouldn't take the bait." (5)

On 17th December, 1974, William Colby called Angleton into his office and told him that he wanted him to retire. He offered him a post as a special consultant, in which he would compile his experiences for the CIA's historical record. "I told him to leave the staff to write up what he had done during his career. This reflected my desire to get rid of him, but in a dignified way - so he could get down his experience on paper. No one knew what he had done! I didn't! I told him to take either the consultancy or honorable retirement. We also discussed that he would get a higher pension if he accepted early retirement... He dug in his heels. I couldn't get him to leave the job on his own. I just couldn't edge him out." (6)

The following day Seymour Hersh, who worked for the New York Times, phoned Colby and told him that he had an important story about the CIA. The two men met on 20th December. Hersh revealed that he had discovered both of the domestic operations run by Angleton - HT-LINGUAL and Operation Chaos. "Hersh told Colby that he intended to publish the news that the CIA had engaged in a massive spying campaign against thousands of American citizens (which violated the CIA charter). Colby tried to contain the damage, and he attempted to correct some of the exaggerations Hersh had picked up. But, in so doing, he effectively confirmed Hersh's information." (7)

Colby now had a meeting with Angleton and told him that Hersh was about to publish a story about his illegal operations. As a result he was forced to sack him. Angleton went to a public pay phone and called Hersh. He begged him not to run the pending story. as an inducement, he promised to give the journalist other classified information to publish instead. "He told me he had other stories which were much better. He really wanted to buy me off with these leads. One of the things he offered sounded very real - he said it was about something the United States was doing inside the Soviet Union. It could have been totally poppycock, who knows. I didn't write it." Angleton later accused Colby of giving information about the illegal operations to Hersh. However, in his interview with Tom Mangold he denied it. (8)

On 22nd December, 1974, Seymour Hersh published his story in the New York Times. Angleton was identified as the head of the CIA's counter-intelligence staff and the man responsible for these illegal operations. David Atlee Phillips, saw him soon after the article was published: "We talked for a few minutes, standing in the diffused glow of a distant light. Angleton's head was lowered, but occasionally he glanced up from under his brim of his black homburg... We then rambled on about nothing particular. I thought to myself that I had never seen a man who looked so infinitely tired and sad." (9)

George Kalaris - Counter-intelligence

George T. Kalaris was appointed to replace James Jesus Angleton. William Colby pointed out: "I put George in there because he's a very good, straightforward fellow. He wasn't flashy. He knew how to run stations, and I had trust and faith in him. The situation needed a sensible person like him to put the place together again after all the chaos. I also needed someone who had not taken a side on any of the major issues.... I wrote George a very basic memorandum of instruction. I ordered him to go to it - to go get agents, to go penetrate the enemy." (10)

Angleton went to see Kalaris on 31st December, 1974. He told the new head of counter-intelligence that he intended to "crush" him. "It's nothing personal. It's just that you are caught in the middle of a big battle between Colby and me. I feel sorry for you. I studied your personnel records, and I repeat, you are going to be crushed." Angleton then went on to criticize the choice of Kalaris to run the department: "To qualify for working on my staff you would need eleven years of continuous study of old cases, starting with The Trust and the Rote Kapelle and so on. Not ten years, not twelve, but precisely eleven. My staff has made detailed study of these requirements. And even that much experience would make you only a journeyman counter-intelligence analyst." Angleton then went on to say that the Soviets had not been successful in compromising the CIA's Counter-intelligence Staff, because he had been there to protect it. "But this is not true of the Soviet Division". (11)

Kalaris now instigated an investigation into Angleton's filing system. His team found "entire sets of vaults and sealed rooms scattered all around the second and third floors of CIA headquarters". They came across over 40 safes, some of them had not been opened for over ten years. No one on Angleton's remaining staff knew what was in them and no one had the combinations anymore. Kalaris was forced to call in a "crack team of safebusters to drill open the door". The investigators found "Angleton's own most super-sensitive files, memoranda, notes and letters... tapes, photographs" and according to Kalaris "bizarre things of which I shall never ever speak". This included files on two senior figures in MI5, Sir Roger Hollis and Graham Mitchell. There were also files on a large number of journalists. (12)

The investigators also found documents concerning Lee Harvey Oswald and on 18th September, 1975, George Kalaris wrote a memo to the executive assistant to the deputy director of Operations of the CIA describing the contents of Oswald's 201 file. "There is also a memorandum dated 16 October 1963 from (redacted but likely Winston Scott) to the United States Ambassador there concerning Oswald's visit to Mexico City and to the Soviet Embassy there in late September - early October 1963. Subsequently there were several Mexico City cables in October 1963 also concerned with Oswald's visit to Mexico City, as well as his visits to the Soviet and Cuban Embassies." (13) As John Newman, the author of Oswald and the CIA (2008) has pointed out: "the significance of the Kalaris memo is that it disclosed the existence of pre assassination knowledge of Oswald's activities in the Cuban Consulate, and that this had been put into cables in October 1963." (14)

The investigators discovered that James Jesus Angleton had not entered any of the official documents from these safes into the CIA's central filing system. Nothing had never been filed, recorded, or sent to the secretariat. "Angleton had been quietly building an alternative CIA, subscribing only to his rules, beyond peer review or executive supervision." Over the next three years "a team of highly trained specialists another three full years just to sort, classify, file, and log the material into the CIA system." Leonard McCoy, was giving the responsibility of inspected the most important files. McCoy was advised "to retain less than one half of 1 per cent of the total, or no more than 150-200 out of the 40,000." The rest of Angleton's files were then destroyed. (15)

George Kalaris, died on at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, in September 1995. He was 73 and had been under treatment for cardiac and kidney problems. (16)

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Mangold, Cold Warrior: James Jesus Angleton: The CIA's Master Spy Hunter (1991)

George Kalaris could not have been more neutral to the Angleton controversies had he come from halfway up the Amazon-which, in effect, he did. Kalaris was chief of station in Brasilia when he received a cable from CIA headquarters on Christmas Eve, 1974, ordering him to return to Washington at once and take over the Counter-intelligence Staff.

The new chief was a slimly built, second-generation Greek American in the mold of Solon. He had a long, prominent nose, a shy, friendly smile, and a generously self-deprecating manner. Originally from Montana, Kalaris had started his Washington career as a civil servant - lawyer in the Labor Department (and spoke fluent French and Greek) before he joined the CIA in 1952. In the course of a notable career in the clandestine side of the house, he became one of Colby's trusted Far East specialists. He worked his way through operational assignments in Indonesia and Laos, and later served as a branch chief

in Colbv's Far East Division. His acquisition of the manuals and actual warhead of the Soviet SA-2 missile was credited by the Defense Intelligence Agency with saving literally hundreds of pilots and countless aircraft over Vietnam.

He had been chief of station in the key Manila posting before moving on to South America.

Kalaris had a natural and practical affinity for clandestine work. Colleagues describe him as a dependable and very fair administrator, who grasped complex problems quickly and made shrewd, insightful judgments. He also maintained a good sense of humor, a prerequisite for the responsibilities of counterintelligence. Furthermore, he understood the craft well, having practiced it regularly at CIA stations in the field. Counterintelligence was not an intellectual challenge to him, nor a major philosophy. He had not been part of the Counterintelligence Staff during the Angleton years; nor had he been involved in any of its internal politicking. Indeed, Kalaris shared nothing with Angleton beyond loyalty to the service and an incurable addiction to nicotine.

(2) David Wise, Molehunt (1992)

Just after Christmas in 1974, Colby called George T. Kalaris home from Brasilia, where he was chief of station, and appointed him chief of counter-intelligence to replace James Angleton.

Kalaris, the son of Greek immigrants who owned restaurants in Billings, Montana, had joined the agency in 1952. He had served for the most part in the Far East, where he had been deputy COS in Laos and chief of station in the Philippines. There he had gotten to know Colby, who headed the Far East division. Kalaris was part of the "FE Mafia," the Asian hands whom Colby had brought in to staff a number of high-level positions in the agency.

As one of his first acts when he took over the CI Staff, Kalaris assigned William E. Camp III, a CIA officer who had served in Oslo at the time of Lygren's arrest and whom Kalaris had recruited for thf CI Staff, to do a study of the case. Camp concluded, even before Haavik's arrest, that the CIA - relying on Golitsin's informationhad bungled, alerting Norway to arrest the wrong woman.

Mortified, Kalaris felt the agency should express its regret to Norway for the false imprisonment of Lygren. In 1976, Camp was dispatched to Oslo with a letter from the CIA, signed by Kalaris apologizing to the government of Norway for the monstrous error ir the Lygren affair. Camp, accompanied by Quentin C. Johnson, the CIA's Oslo station chief, called on the Norwegian authorities and delivered the letter and a verbal apology as well. The CIA also offered Lygren money, in addition to the small compensation she had received from her own government, an offer that the Norwegians turned down

Kalaris also took steps to ensure that Lygren herself was made aware of the agency's contrition. But the official CIA apology to the government of Norway was never made public. By that time, In geborg Lygren had retired into obscurity near her native Stavanger, ii southwest Norway, her telephone unlisted, her only wish to live ou her days quietly and unnoticed.

On January 22, 1991, it was disclosed through an item inserted in the Oslo paper by her family that Ingeborg Lygren had died in Sandnes, a suburb of Stavanger, at the age of seventy-six.

(3) David Binder, The New York Times (14th September, 1995)

George T. Kalaris, the officer assigned in 1974 by the Central Intelligence Agency to clean up one of its worst internal messes, a seemingly endless hunt for a Soviet agent in its own ranks, died on Monday at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md. He was 73 and had been under treatment for cardiac and kidney problems.

Until his appointment in 1974 as chief of the counterintelligence staff, running the innermost sanctum of the agency, Mr. Kalaris had spent most of his career as a clandestine operations officer in Greece, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines and Brazil. He won special admiration, for his central role in acquiring a warhead and operational manuals for a Soviet SA-2 anti-aircraft missile in Indochina.

Before Mr. Kalaris's appointment, a kind of paralysis had developed in the counterintelligence staff, which had been led from its outset by James J. Angleton, who had an obsession with finding a Soviet spy in the agency. The paralysis had spread to the Soviet-East European Division, where at least a dozen officers were under his suspicion.

The newly installed head of the agency, William E. Colby, dealt with the problem by dismissing Mr. Angleton and replacing him on Dec. 31, 1974, with Mr. Kalaris.