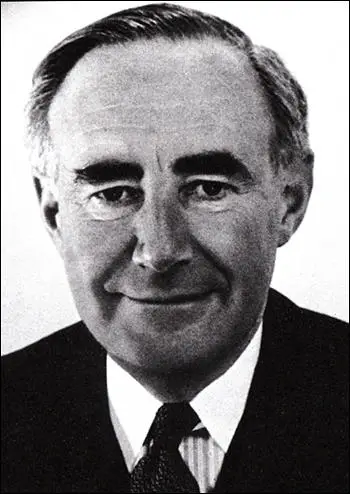

Graham Mitchell

Graham Mitchell, he only son and elder child of Alfred Sherrington Mitchell, and his wife, Sibyl Gemma Heathcote, was born in Kenilworth on 4th November 1905. He was educated at Winchester College and Magdalen College, where he read politics, philosophy, and economics. As his biographer, Nigel West, has pointed out: "In spite of suffering from poliomyelitis while still at school he excelled at golf and sailed for his university. He was also a very good lawn tennis player, and won the Queen's Club men's doubles championship in 1930. He played chess for Oxford, and was later to represent Great Britain at correspondence chess, a game at which he was once ranked fifth in the world. He obtained a second class honours degree in 1927." (1)

After leaving Oxford University he worked as a journalist on the Illustrated London News. His next job was in the research department of Conservative Party central office which was then headed by Sir George Joseph Ball. On the outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1939, he joined MI5. It is believed that Ball arranged for him to join the service.

Graham Mitchell - MI5

Mitchell's first post in MI5 was in the F3 sub-section of F division, the department headed by Roger Hollis responsible for monitoring subversion. F3's role was to maintain surveillance on right-wing nationalist movements such as the British Union of Fascist, the Right Club and the Anglo-German Fellowship and individuals suspected of pro-Nazi sympathies. One of Mitchell's first tasks was to investigate the activities of Sir Oswald Mosley and collate the evidence used to support his subsequent detention.

At the end of the war Mitchell was promoted to the post of director of F division, where he remained until 1952 when he was switched to the counter-espionage branch, D branch. Peter Wright worked with Mitchell during this period: "The head of D Branch, Graham Mitchell, was a clever man, but he was weak. His policy was to cravenly copy the wartime Double Cross techniques, recruiting as many double agents as possible, and operating extensive networks of agents in the large Russian, Polish, and Czechoslovakian emigre communities. Every time MI5 were notified of or discovered a Russian approach to a student, businessman, or scientist, the recipient was encouraged to accept the approach, so that MI5 could monitor the case. He was convinced that eventually one of these double agents would be accepted by the Russians and taken into the heart of the illegal network." (2)

Mitchell's staff of 30 officers monitored over 300 Soviet intelligence officers working under diplomatic cover. While in charge of D Branch he led the team of case officers pursuing the clues of Soviet penetration left by Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, the two diplomatists who defected to Moscow in May 1951. He was also one of the chief architects of positive vetting, the screening procedure introduced in Whitehall to prevent Soviet agents "from penetrating the higher echelons of the civil service. In addition Mitchell was the principal author of the notorious 1955 white paper on the Burgess and Maclean defection." (3)

Deputy Director-General

In 1956 Roger Hollis succeeded Sir Dick White as director-general of MI5 and he selected Mitchell as his deputy. Peter Wright has pointed out: "There were only two really striking things about Mitchell's career. One was the way it was intimately bound up with Hollis'. They had been contemporaries at Oxford, joined MI5 at around the same time, and followed each other up the ladder in complementary positions. The second was the fact that Mitchell seemed to be an underachiever. He was a clever man, picked by Dick White to transform D Branch. He signally failed to do so in the three years he held the job, and indeed, when the decision to close VENONA down was taken into account, it seemed almost as if he was willfully failed." (4)

This was a difficult time for the service. In December 1961, Anatoli Golitsin, a KGB agent, working in Finland, defected to the CIA. He was immediately flown to the United States and lodged in a safe house called Ashford Farm near Washington. Interviewed by James Angleton Golitsin supplied information about a large number of Soviet agents working in the West. Arthur Martin, head of MI5's D1 Section, went to to interview Golitsin in America. Golitsin provided evidence that suggested that Kim Philby had been a member of a Ring of Five agents based in Britain. (5)

An old friend, Flora Solomon, was also feeling hostile to Philby. She disapproved of what she considered were Philby's pro-Arab articles in The Observer. It has been argued that "her love for Israel proved greater than her old socialist loyalties." (6) In August 1962, during a reception at the Weizmann Institute, she told Victor Rothschild, who had worked with MI6 during the Second World War and enjoyed close connections with Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service: "How is it that The Observer uses a man like Kim? Don't the know he's a Communist?" She then went on to tell Rothschild that she suspected that Philby and his friend, Tomas Harris, had been Soviet agents since the 1930s. "Those two were so close as to give me an intuitive feeling that Harris was more than a friend."

Armed with Solomon's information, Philby's friend and former SIS colleague Nicholas Elliott flew out from London at the beginning of 1963 to confront him in Beirut, where he was working as a journalist. According to Philby's later version of events given to the KGB after he escaped to Moscow, Elliott told him: "You stopped working for them (the Russians) in 1949, I'm absolutely certain of that... I can understand people who worked for the Soviet Union, say before or during the war. But by 1949 a man of your intellect and your spirit had to see that all the rumours about Stalin's monstrous behaviour were not rumours, they were the truth... You decided to break with the USSR... Therefore I can give you my word and that of Dick White that you will get full immunity, you will be pardoned, but only if you tell it yourself. We need your collaboration, your help." (7)

Kim Philby

Roger Hollis wrote to J. Edgar Hoover on 18th January 1963, about Elliott's discussions with Kim Philby: "In our judgment Philby's statement of the association with the RIS is substantially true. It accords with all the available evidence in our possession and we have no evidence pointing to a continuation of his activities on behalf of the RIS after 1946, save in the isolated instance of Maclean. If this is so, it follows that damage to United States interests will have been confined to the period of the Second World War." (8) This statement was undermined by the decision of Philby to flee to the Soviet Union a week later.

Arthur Martin, head of the Soviet counter-espionage section, and Peter Wright spent a great deal listening to the confession that Philby had made to Nicholas Elliott. Wright later argued: "There was no doubt in anyone's mind, listening to the tape, that Philby arrived at the safe house well prepared for Elliott's confrontation. Elliott told him there was new evidence, that he was now convinced of his guilt, and Philby, who had denied everything time and again for a decade, swiftly admitted spying since 1934. He never once asked what the new evidence was." Both men came to the conclusion that Philby had not asked about the new evidence as he had already been told about it. This convinced them that the "Russians still had access to a source inside British Intelligence who was monitoring the progress of the Philby case. Only a handful of officers had such access, chief among them being Hollis and Mitchell." (9)

Plans for Philby's interrogation were known to five members of the Service, of whom only Hollis and Mitchell had long enough service and good enough access to classified information to fit the profile of a long-term penetration agent. Martin, according to Christopher Andrew, was the "Service's leading conspiracy theorist at the time of Philby's defection, believed Mitchell was the chief suspect. Martin claimed that Mitchell "had the reputation of being a Marxist during the war". An "assertion, which, he later acknowledged, rested only on (inaccurate) hearsay evidence." (10)

Martin took his conspiracy theories to Dick White, the Chief of the SIS. White refused to believe Hollis was a Soviet spy but agreed to contact him about his suspicions concerning Mitchell. On 7th March 1963, Martin attended a meeting with Hollis. Martin later recalled that while explaining his theory that Mitchell was a Soviet agent, Hollis reacted in a strange way: "He (Hollis) sat hunched up at his desk, his face drained of colour and with a strange half-smile playing on his lips. I had framed my explanation so that it led to the conclusion that Graham Mitchell was in my mind, the most likely suspect... I had expected that my theory would at least be challenged but it received no comment other than I had been right to voice it and he would think it over." (11)

Graham Mitchell - Soviet Spy?

On 13th March 1963 Arthur Martin was told that he could make "discreet enquiries" into Mitchell's background, which he was to report to Martin Furnival Jones. As Chapman Pincher pointed out: "It had been decided, in order to dispose of the case against Mitchell one way or the other and as quickly as possible, he should be given the full technical treatment. A mirror in his office was removed and made see-through by resilvering so that a television camera could be hidden behind it, the object being to allow the investigators to see if Mitchell was in the habit of copying secret documents." (12)

Peter Wright was one of those involved in the surveillance operation. "I treated his ink blotter with secret-writing material, and every night it was developed, so that we could check on everything he wrote. But there was nothing beyond the papers he worked on normally... I asked him (Hollis) for his consent to pick the locks of two of the drawers which were locked. He agreed and I brought the lockpicking tools the next day, and we inspected the insides of the two drawers. They were both empty, but one caught my attention. In the dust were four small marks, as if an object had been very recently dragged out of the drawer." This made Wright suspicious of Hollis: "Only Hollis and I knew I was going to open the drawer and something has definitely been moved... Why not Mitchell? Because he didn't know. Only Hollis knew." (13)

However, Martin began to suspect that Mitchell had been told he was under investigation. "He wandered about in parks, repeatedly turning around as though to check that he was not being followed. In the street, he would peer into shop windows, looking for the reflections of passers-by. He also wore tinted spectacles, which might enable him, from the reflections, to see anyone who might be on his trail. The 'candid camera' in his office revealed that whenever he was alone, his face looked tortured as though he were in deep despair." (14)

The investigation was unable to find any conclusive evidence that Mitchell was a Soviet spy. Hollis wanted to keep the investigation secret. However, Dick White, the head of the SIS, pointed out that this would break the Anglo-American agreement on security. White told the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, and he was forced to tell President John F. Kennedy. Hollis was sent to Washington to have a meeting with J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI and John McCone and James Jesus Angleton, of the FBI. Hollis told them that "I have come to tell you that I have reason to suspect that one of my most senior officers, Graham Mitchell, has been a long-term agent of the Soviet Union." (15)

Mitchell's biographer argues that after the investigation Mitchell was a broken man: "The evidence accumulated against Mitchell was all very circumstantial, and centred on the poor performance of MI5's counter-espionage branch during the 1950s. During this period MI5 experienced a number of set-backs, failed to attract a single Soviet defector, and only caught one spy on its own initiative. "During the last five months of his career Mitchell was the subject of a highly secret and inconclusive ‘molehunt’ which was eventually terminated." (16) As a result of the investigation, Mitchell decided to retire early from MI5.

Arthur Martin was disappointed when it was discovered that Roger Hollis and the British government had decided not to put Anthony Blunt on trial. Martin once again began to argue that there was still a Soviet spy working at the centre of MI5 and that pressure should be put on Blunt to make a full confession. Hollis thought Martin's suggestion was highly damaging to the organization and ordered Martin to be suspended from duty for a fortnight. Martin offered to carry on with the questioning of Blunt from his home, but Hollis forbade it. As a result, Blunt was left alone for two weeks, and nobody knows what he did... Soon afterward, Hollis picked another quarrel with Martin, and though he was very senior, summarily sacked him. Martin believes that Hollis sacked him because he feared him, but his action did Hollis little good, whatever his motive." (17)

Dick White, the head of MI6, agreed with Martin that suspicions remained about the loyalty of Hollis and Mitchell. In November, 1964, White recruited him and immediately nominated Martin as his representative on the Fluency Committee, that was investigating the possibility of Soviet spies in British intelligence. The committee initially examined some 270 claims of Soviet penetration, which were later whittled down to twenty. It was claimed that these cases supported the claims made by Konstantin Volkov and Igor Gouzenko that there was a high-level agent in MI5. (18)

In 1974 Harold Wilson asked Lord Burke Trend to investigate the possibility that Graham Mitchell and Roger Hollis were Soviet spies. He was unable to reach a definite decision. Trend concluded: "Mitchell's curious behaviour is reasonably explicable on the assumption that it represented the natural reaction of a highly strung and rather odd individual to the strain of working for a DG (Hollis) with whom he was increasingly out of sympathy." (19)

Graham Mitchell died at his home, 3 Field Close, Sherington, Buckinghamshire, on 19 November 1984.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

The head of D Branch, Graham Mitchell, was a clever man, but he was weak. His policy was to cravenly copy the wartime Double Cross techniques, recruiting as many double agents as possible, and operating extensive networks of agents in the large Russian, Polish, and Czechoslovakian emigre communities. Every time MI5 were notified of or discovered a Russian approach to a student, businessman, or scientist, the recipient was encouraged to accept the approach, so that MI5 could monitor the case. He was convinced that eventually one of these double agents would be accepted by the Russians and taken into the heart of the illegal network.

The double-agent cases were a time-consuming charade. A favorite KGB trick was to give the double agent a parcel of money or hollow object (which at that stage we could inspect), and ask him to place it in a dead letter drop. D Branch was consumed every time this happened. Teams of Watchers were sent to stake out the drop for days on end, believing that the illegal would himself come to clear it. Often no one came to collect the packages at all or, if it was money, the KGB officer who originally handed it to the double agent would himself clear the drop. When I raised doubts about the double-agent policy, I was told solemnly that these were KGB training procedures, used to check if the agent was trustworthy. Patience would yield results.

(2) George A. Carver, The Fifth Man, Atlantic Online (September 1988)

If there actually was such a fifth man, the pool of serious candidates, with the requisite access and seniority, is very small. Indeed, it probably consists of no more than three people.

One is Guy Liddell, who was the deputy director general of MI5 from 1947 until he retired, in 1952. He, Burgess, and Blunt were friends, and Liddell was very much a part of the hothouse wartime circle revolving around Victor Rothschild's 5 Bentinck Street flat, in which Burgess and Blunt both lived. During the war Liddell ran MI5's counterespionage division, where Anthony Blunt was his personal assistant. Philby had a high regard for Liddell, whom he described in My Silent War - with Empsonian ambiguity - as "an ideal senior officer for a young man to learn from." In 1944 Liddell assisted Philby in the successful bureaucratic knifing of Philby's then superior, Felix Cowgill, so that Philby could become the head of SIS's expanding counterintelligence effort (which Philby terms his "Fulfillment"). Liddell, however, was greatly admired, professionally and personally, and has many staunch defenders. These include Sir Dick White, Philby's nemesis in both MI5 and MI6, both of which White headed, and Peter Wright (of Spycatcher fame), one of the most avid of all mole-hunters.

The two others are Graham Mitchell and Sir Roger Hollis. In 1951 Mitchell was in charge of counterespionage; he became deputy director general of MI5 (under Hollis) in 1956 and retired in 1963. He drafted the patently mendacious, demonstrably erroneous 1955 white paper on the Burgess-Maclean defection. On the strength of that document the Foreign Secretary, Harold Macmillan, gave Philby what the latter would call the happiest day of his life by publicly affirming Philby's innocence in the House of Commons - declaring, in a statement that Mitchell helped draft, that Philby was not the third man ("if indeed, there was one"). Hollis became deputy in 1953 and moved up in 1956 to be director general until his retirement, in 1965. Mitchell and Hollis were the subject of a series of investigations during the 1960s. Both were eventually declared innocent of any wrongdoing.

(3) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

We turned to the tapes of Philby's so-called "confession," which Nicholas Elliott brought back with him from Beirut. For many weeks it was impossible to listen to the tapes, because the sound quality was so poor. In typical MI6 style, they had used a single low-grade microphone in a room with the windows wide open. The traffic noise was deafening! Using the binaural tape enhancer which I had developed, and the services of Evelyn McBarnet and a young transcriber named Anne Orr-Ewing, who had the best hearing of all the transcribers, we managed to obtain a transcript which was about 80 percent accurate. Arthur and I listened to the tape one afternoon, following it carefully on the page. There was no doubt in anyone's mind, listening to the tape, that Philby arrived at the safe house well prepared for Elliott's confrontation. Elliott told him there was new evidence, that he was now convinced of his guilt, and Philby, who had denied everything time and again for a decade, swiftly admitted spying since 1934. He never once asked what the new evidence was.

Arthur found it distressing to listen to the tape; he kept screwing up his eyes, and pounded his knees with his fists in frustration as Philby reeled off a string of ludicrous claims: Blunt was in the clear, but Tim Milne, an apparently close friend of Philby's, who had loyally defended him for years, was not. The whole confession, including Philby's signed statement, looked carefully prepared to blend fact and fiction in a way which would mislead us. I thought back to my first meeting with Philby, the boyish charm, the stutter, how I sympathized with him; and the second time I heard that voice, in 1955, as he ducked and weaved around his MI6 interrogators, finessing a victory from a steadily losing hand.

And now there was Elliott, trying his manful best to corner a man for whom deception had been a second skin for thirty years. It was no contest. By the end they sounded like two rather tipsy radio announcers, their warm, classical public-school accents discussing the greatest treachery of the twentieth century.

"It's all been terribly badly handled," moaned Arthur in despair as the tape flicked through the heads. "We should have sent a team out there, and grilled him while we had the chance..."

I agreed with him. Roger and Dick had not taken into account that Philby might defect.

On the face of it, the coincidental Modin journeys, the fact that Philby seemed to be expecting Elliott, and his artful confession all pointed in one direction: the Russians still had access to a source inside British Intelligence who was monitoring the progress of the Philby case