Major George Joseph Ball

George Joseph Ball was born at 24 Inkerman Street, Luton, Bedfordshire, on 21st September 1885, the son of George Ball, bookstall clerk, of Salisbury, and his wife, Sarah Ann Headey. Ball was educated at King's College School, Strand, and at King's College, London. After leaving college he worked as a civilian official in Scotland Yard, and he was called to the bar with first-class honours by Gray's Inn in 1913. (1)

On 16th April 1914 he married Gladys Emily Penhorwood, a school teacher, daughter of John Burch Penhorwood. During the First World War he joined the Directorate of Military Intelligence Section 5 (MI5). According to Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "Ball had joined MI5 in July 1915 after a decade at Scotland Yard, dealing mainly with aliens. He was also a barrister, having passed top of the Bar final exams, and spent much of the war questioning prisoners, internees, suspects and aliens." (2)

In 1916 MI5 set up Ministry of Munitions Intelligence Agency (PMS2) to spy on the British socialist movement. Major William Melville Lee was appointed as head of PMS2 and Ball became one of his agents. PMS2 agents, Herbert Booth and Alex Gordon, were used to set-up three members of the Socialist Labour Party in Derby. On 10th March 1917, The judge disagreed with the objection to the use of secret agents. "Without them it would be impossible to detect crimes of this kind." However, he admitted that if the jury did not believe the evidence of Booth, then the case "to a large extent fails". (3)

Major George Bell and Alice Wheeldon

The jury did believe the testimony of Booth and after less than half-an-hour of deliberation, they found Alice Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason guilty of conspiracy to murder. Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison. Alfred got seven years whereas Winnie received "five years' penal servitude." Three days after the conviction, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, published an open letter to the Home Secretary that included the following: "We demand that the Police Spies, on whose evidence the Wheeldon family is being tried, be put in the Witness Box, believing that in the event of this being done fresh evidence will be forthcoming which will put a different complexion on the case." (4)

Basil Thomson, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, was also unconvinced by the guilt of Alice Wheeldon and her family. Thomson later said that he had "an uneasy feeling that he himself might have acted as what the French call an agent provocateur - an inciting agent - by putting the idea into the woman's head, or, if the idea was already there, by offering to act as the dart-thrower." This controversial case resulted in the PMS2 being "reabsorbed" by MI5 in 1917. Vernon Kell, however, made clear that he did not want back officers who had been "concerned with labour unrest and strikes". However, Ball remained in MI5. (5)

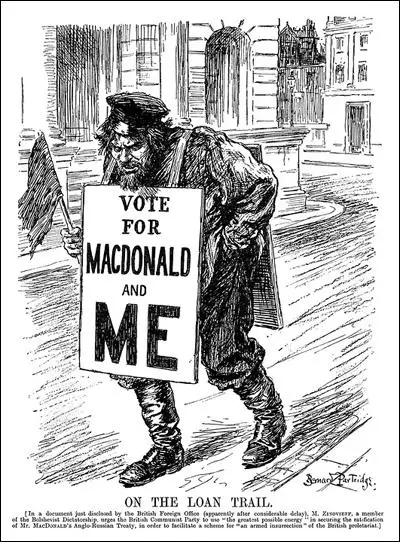

Zinoviev Letter

Gladys Ball died in 1918 and on 6th October 1919, Ball married her half-sister Mary Caroline Penhorwood, with whom he had two sons and one daughter. According to Edward H. Cookridge, Ball also had a homosexual relationship with Guy Burgess, who later became a spy for the Soviet Union and was part of the group that included Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and James Klugmann. (6)

Ball continued to work for MI5 as well as the Conservative Party and it is claimed that he played an important role in the bringing down Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour government and is believed to be involved in what is now known as the forged Zinoviev Letter. (7) On 10th October 1924, MI5 received a copy of a letter, dated 15th September, sent by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, to Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were asked to take all possible action to ensure the ratification of the Anglo-Soviet Treaties. It then went on to advocate preparation for military insurrection in working-class areas of Britain and for subverting the allegiance in the army and navy. (8)

Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect. (9) Vernon Kell, the head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the letter was genuine. Desmond Morton, who worked for MI6, told Sir Eyre Crowe, at the Foreign Office, that an agent, Jim Finney, who worked for George Makgill, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), had penetrated Comintern and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Morton told Crowe that Finney "had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter". However, Christopher Andrew, who examined all the files concerning the matter, claims that Finney's report of the meeting does not include this information. (10)

Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret. (11) Thomas Marlowe, who worked for the press baron, Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, had a good relationship with Reginald Hall, the Conservative Party MP, for Liverpool West Derby. During the First World War he was director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID) and he leaked the letter to Marlowe, in an effort to bring an end to the Labour government. (12)

The newspaper now contacted the Foreign Office and asked if it was a forgery. Without reference to MacDonald, a senior official told Marlowe it was genuine. The newspaper also received a copy of the letter of protest sent by the British government to the Russian ambassador, denouncing it as a "flagrant breach of undertakings given by the Soviet Government in the course of the negotiations for the Anglo-Soviet Treaties". It was decided not to use this information until closer to the election. (13)

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (14)

Dora Russell, whose husband, Bertrand Russell, was standing for the Labour Party in Chelsea, commented: "The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister." (15)

After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter. It later became clear that Major George Joseph Ball, head of B Branch, who passed the letter onto Conservative Central Office on 22nd October, 1924. Christopher Andrew, MI5's official historian, points out: "Ball's subsequent lack of scruples in using intelligence for party political advantage while at Central Office in the late 1920s strongly suggests... that he was willing to do so during the election campaign of October 1924." (16)

Major Ball was highly regarded at MI5 and earned himself a string of commendations from his superiors, who wrote of him that he was "an officer of marked ability, capable and willing to assume responsibility" and that he was "first class". His work was so valued that MI5 increased his salary up from £700 to £800 in hope of retaining his services. (17)

Ball's biographer, Robert Blake, has pointed out: "Ball moved for most of his life in the shadow of events and was deeply averse to publicity of any sort. He gave very little away, and the formal accounts of his career, whether written by himself or others, are curt and uninformative. He was, however, a quintessential éminence grise, and his influence on affairs cannot be measured by the brevity of the printed references to him." (18)

Director of the Conservative Research Department

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1986) has pointed out that the Conservative Party were grateful that Major Ball via the Zinoviev Letter "had made disreputable use of secret intelligence for political advantage". Ball was rewarded in March 1927 when he was appointed as Deputy of Publicity at the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring on the exorbitant salary of £1,400. (19)

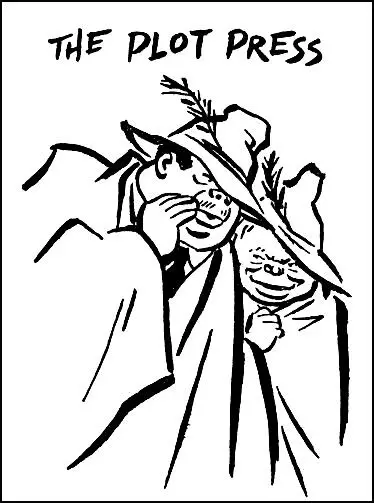

John C. Davidson, the MP for Hemel Hempstead, recruited him to help run "a little intelligence service of our own". As Davidson pointed out: "We had agents (ran by Joseph Ball) in certain key centres and we also had agents actually in the Labour Party Headquarters, with the result that we got their reports on political feeling in the country as well as our own. We also got advance "pulls" of their literature. This we arranged with Odhams Press, who did most of the Labour Party printing, with the result that we frequently received copies of their leaflets and pamphlets before they reached Transport House (the Labour HQ). This was of enormous value to us because we were able to study the Labour Party policy in advance, and in the case of leaflets we could produce a reply to appear simultaneously with their production." (20)

Ball was described by Robert Bernays as "a hard and humourless man" and by another MPs as "a burly, slightly sinister figure" or as "a tubby man with a dark twinkling eye, persistent but elusive". Ball also coordinated the secret selling of honours to Conservative supporters and paid off their intermediary, Maundy Gregory when he was arrested and charged with illegally selling honours and agreed to plead guilty, thereby preventing a trial, which could have brought down the government. (21)

In 1930 Major Ball was promoted to the post of Director of the Conservative Research Department and his "election strategy made a major contribution to the enormous size of the National Government's majority" in the 1931 General Election. (22) Over the next 15 years he developed the strategy of using dirty tricks and black propaganda. This included operating secret agents in the Labour Party and Liberal Party. One historian has claimed that Ball was Britain's first spin-doctor. Ball worked under Neville Chamberlain, the chairman of the Conservative Party. The two men became very close and Ball is said to have taught Chamberlain the art of fly-fishing. (23)

Major Ball and the British Union of Fascists

Oswald Mosley formed the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1st October, 1932. Mosley told his members: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live." (24)

Over the next few months a large number of people joined the organisation such as Charles Bentinck Budd, Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere), Major General John Fuller, Wing-Commander Louis Greig, A. K. Chesterton, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), Unity Mitford, Diana Mitford, Patrick Boyle (8th Earl of Glasgow), Malcolm Campbell and Tommy Moran. Mosley refused to publish the names or numbers of members but the press estimated a maximum number of 35,000. (25)

Mosley was also an outspoken anti-Semite and his dislike of the Jews was appealing to those who had previously voted for the Conservative Party. One of the reasons for this was the anti-Semitic speeches made by Tory MPs. For example, Edward Doran, asked the Home Secretary to prevent "any alien Jews entering this country from Germany". When he refused this request Doran suggested that there would be "hundreds of thousands of Jews.. scurrying .. to this country" and demanded that "undesirable aliens" already in the country to be given notice to quit. (26)

Crawford Greene the Tory MP for Worcester agreed with Doran about Jews causing trouble at British Union of Fascists meetings. Greene argued that 90 per cent of those accused of attacking fascists rejoiced in "such fine old British names such as Ziff, Kerstein and Minsky". (27) Frederick Macquisten, the MP for Argyllshire added that those arrested included "Feigenbaum, Goldstein and Rigotsky and other good Highland names." (28) Arthur Bateman, the Tory MP for Camberwell North claimed that "we have lost the City of London to the Jews" and demanded that "before long we shall have to declare war on them as they have done in Germany". (29)

Major Ball became concerned about this development as it was taking support from the Conservative Party. He was especially concerned by the membership of Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere) the owner of The Daily Mail, a newspaper that had always championed the Tories. Lord Rothermere wrote an article, Hurrah for the Blackshirts, on 22nd January, 1934, in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W." (30)

Ball also had the support of the Daily Telegraph but thought it more important to persuade the Daily Express and the Daily Mail to praise the activities of right-wing dictators. Ball wrote to Stanley Baldwin that although The Times and The Daily Telegraph are admirable papers and give us their full support, their circulations are so small... that their influence among the masses is almost negligible". (31)

Another part of the strategy was to convince Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere) the owner of the The Daily Mail and the Evening News and Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), the owner of the The Daily Express and the Evening Standard, to give its full support to the Conservative Party and to reduce the good publicity it had been giving to Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Ball also persuaded industrialists to transfer financial support from the BUF to the Tories. This included a donation of £75,000 (£2.5m) from William Morris (Morris Motors). The following year Morris became Viscount Nuffield. The industrialists returned to the Tories because they saw it "as the best defence against a unionized and politicized working class with whom they were perpetually in conflict." (32)

Neville Chamberlain

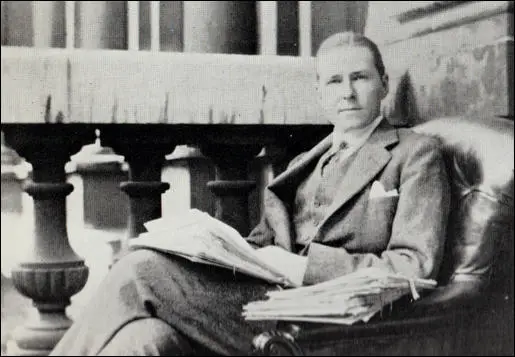

On 28th May, 1937, Stanley Baldwin resigned and replaced by Neville Chamberlain. As Chancellor of the Exchequer he had resisted attempts to increase defence spending. Over the next two years Chamberlain's Conservative government became associated with the foreign policy that later became known as appeasement. Chamberlain believed that Germany had been badly treated by the Allies after it was defeated in the First World War. He therefore thought that the German government had genuine grievances and that these needed to be addressed. He also thought that by agreeing to some of the demands being made by Adolf Hitler of Germany and Benito Mussolini of Italy, he could avoid a European war. (33)

Soon after becoming prime minister, Chamberlain appointed Ball as his political adviser. Chris Bryant pointed out that this was a shrewd move: "Ball was a passionate Conservative and Unionist with a deep hatred of socialism, communism and all points in between. Ball also had a keen understanding of the dark arts of political manipulation, a readiness to use all means at his disposal and an ability to keep himself out of the limelight... he knew how to lie and how to keep a secret." (34)

John C. Davidson was well aware of Ball's shady past: "Joseph Ball and I have been associated for a great many years, and is undoubtedly tough and has looked after his own interests... On the other hand, he is steeped in the Intelligence Service tradition, and has had as much experience as anyone I know in the seamy side of life and the handling of crooks." (35)

Chamberlain asked Ball to run black operations against his critics: "Ball had already been cultivating close personal contacts in the press, the BBC and the British film industry. He had courted all the newspaper barons. Now he provided pliable journalists from supportive newspapers with twice-weekly briefings away from prying eyes at the St Stephen's Club opposite Westminster Bridge on the completely deniable understanding that he knew the PM's mind. He rewarded those who filed supportive copy with titbits of gossip and bullied critics into rejecting derogatory articles." (36)

Ball also protected Chamberlain's relationship with right-wing dictators such as Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco. This involved persuading the BBC and newspaper editors to downplay atrocities committed by Franco's troops in the Spanish Civil War and by the authorities in Nazi Germany. Ball was also keen on presenting Hitler and Mussolini in a positive light. Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, wrote that he did his utmost "night after night, to keep out of the paper anything that might have hurt (the Germans') susceptibility." (37)

George Joseph Ball and the BBC

Tim Bouverie, the author of Appeasing Hitler: Chamberlain, Churchill and the Road to War (2020) argues that it was not difficult for Ball to manipulate the media as it was inherently a supporter of the Conservative Party and the "most influential elements of that industry" did not need "to be pressured into taking the Government line." He quotes the BBC Director General, John Reith, as saying "assuming that the BBC is for the people, and the Government is for the people, it follows that the BBC must be for the Government." Bouverie adds "a sophistry which also applied to a number of newspapers." (38)

Reich and the BBC willingly gave its support to Neville Chamberlain. It was told by Ball that Chamberlain did not want the BBC to give an opportunity of his opponents to give "independent expressions of opinion". Winston Churchill was effectively banned from the BBC during Chamberlain's first two years at Number 10. Churchill commented at the time: "If we could get access to the broadcast some progress could be made. All this is very carefully sewn up over here." (39)

Reith had been a supporter of Adolf Hitler since he took power by force in 1933. In his diary he wrote about the problems of radio broadcasting in Nazi Germany. Reith's daughter, Marista Leishman, in her book, My Father: Reith of the BBC (2008), claims Reith was reluctant to acknowledge the truth about the Nazis, actually arguing in their favour with another German contact in November 1933. (40)

Reith wrote in his diary: "Dr. Wanner (head of broadcasting for southern Germany) to see me in much depression. He said he would like to leave his country and never return. I am pretty certain, however, that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again. They are being ruthless and most determined. It is mostly the fault of France that there should be such manifestations of national spirit." (41)

Leishman claims her father told Guglielmo Marconi in 1935 that he admired Hitler for his "magnificent efficiency". She quotes Asa Briggs as saying that Reith's "notions of social and industrial regimentation inclined towards fascism". "John Reith made no apology for announcing that he really admired the drastic action taken by Hitler. At home, he liked to draw Muriel's attention to the way in which some of her relatives looked Jewish - with the implication that she did too - as though that were a black mark. I began to think that, in many ways, my father must be a rather terrible person." (42)

Adolf Hitler appointed Joachim von Ribbentrop as the ambassador to London in August, 1936. His main objective was to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany territorial disputes and to work together against the the communist government in the Soviet Union. Ribbentrop upset the British government by posting Schutz Staffeinel (SS) guards outside the German Embassy and by flying swastika flags on official cars. However, BBC Director General, John Reith got on very well with him. According to Reith's own diary he told Rippentrop to assure Hitler "the BBC was not anti-Nazi" and that if they were to send his German opposite number over for a visit he would fly the swastika from the top of Broadcasting House. (43)

Labour Party MPs became increasingly concerned by what they thought was the BBC's pro-Nazi stance. Hastings Lees-Smith argued in the House of Commons: "The BBC is an autocracy which has outgrown the original autocrat ... It has become despotism in decay ... the nearest thing in this country to Nazi government that can be shown... If I talk to any employee of the Corporation, I am made to feel like a conspirator." (44)

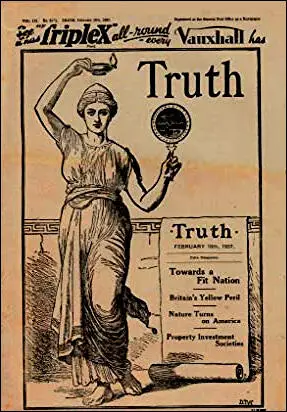

Acquisition of The Truth

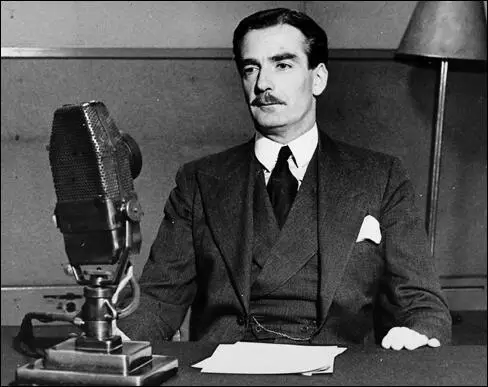

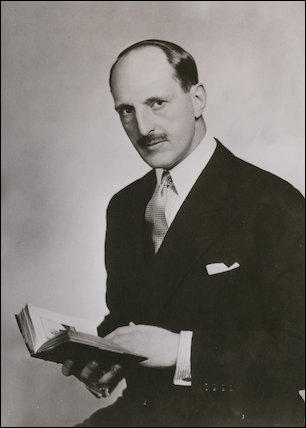

With the help of wealthy businessman, George Lawson Johnson (Lord Pavenham), the heir to the Boveril empire and chairman of the fundraising arm of the Conservative Party's National Publicity Bureau, in 1937 Ball secretly purchased The Truth journal. Henry Newnham was appointed editor and A. K. Chesterton and Collin Brooks, both members of the British Union of Fascists, were recruited to write articles for the magazine. The main objective of the journal was to attack any Tory MPs who criticized Chamberlain's government. When the MP for Tiverton, Lieutenant Colonel Gilbert Acland-Troyte, complained about the government's agricultural policy, the magazine accused him of having "blimp blood in his veins" and of having been "overtaken by a rhetorical bilious attack". (45)

However, the main purpose of The Truth was to attack those Tory MPs who opposed appeasement. This included Chamberlain's Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain announced he was sending his friend, and fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring in Germany. Eden was furious when he discovered this and felt he was being undermined as foreign secretary. One historian has commented: "Eden and Chamberlain seemed like two horses harnessed to a cart, both pulling in different directions." (46)

In his diary, Halifax records how he told Hitler: "Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country." This was a reference to the fact that Hitler had banned the Communist Party (KPD) in Germany and placed its leaders in Concentration Camps. Halifax told Hitler: "On all these matters (Danzig, Austria, Czechoslovakia) ... the British government... "were not necessarily concerned to stand for the status quo as today... If reasonable settlements could be reached with... those primarily concerned we certainly had no desire to block." (47)

Lord Halifax later explained that Hitler told him that Czechoslovakia "only needed to treat the Germans living within her borders well and they would be entirely happy". He also had meetings with Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Hjalmar Schacht and Werner von Blomberg. Göring informed Halifax that Germany did not intend to fight to gain colonies. Blomberg said that Anglo-German relations were more important than the "colonial question" but Germany were interested in taking territory in Central Europe. (48)

Negotiations with Benito Mussolini

In 1937 Major Ball developed a relationship with Adrian Dingli, a British barrister and legal counsellor at the Italian Embassy who had been raised in Malta (his father was the Chief Justice of the island between 1880-1900). Ball got to know Dingli at the Carlton Club "where the British Empire's movers and shakers met was testament to his Britishness." As Giorgio Peresso has pointed out: "Chamberlain believed that since both Britain's economy and its military defences were weak, the best bet was appeasement to the Nazi-Fascist regimes to avoid war. His Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, believed that appeasement facilitated the possibility of war. Nevertheless, the British prime minister was determined to reach an accommodation with the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini." (49)

On 10th January, 1937, Ball told Dingli that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain "wished to know whether Grandi would obtain permission from Rome to start 'talks' in London with the PM". Dingli was suspicious, but Ball assured him that, with Eden abroad, Chamberlain was acting Foreign Secretary and the "suggestion represented the view of the PM". David Faber argued: "Grandi was in Rome at the time, and Ball knew that any message sent en clair by telegram would be deciphered by British intelligence and passed to the Foreign Office, and thus to Eden. Incredibly, it necessitated a series of guarded telephone calls between London and Rome to convey the gist of Chamberlain's message without the information reaching the ears of his own Foreign Secretary." (50)

It was originally arranged for Chamberlain to meet Ambassador Count Dino Grandi on 17th January. However, this was cancelled when Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Deputy Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs discovered what was going on. Ball and Dingli now created an unofficial diplomatic channel which allowed Chamberlain to communicate with the Italian Government behind the backs of the Foreign Office and vice versa. It was a deliberate attempt to circumvent Anthony Eden, who was adamant that no further concessions should be made to Italy unless and until she verifiably withdrew her support for General Francisco Franco and abandoned her claim to Abyssinia. (51)

This development was almost entirely to the Italians' advantage. This unofficial diplomatic channel was welcomed by Benito Mussolini as he could see how it would cause conflict within the British government and as the Italian Ambassador Count Dino Grandi pointed out it provided an opportunity to "drive a wedge into the incipient split between Eden and Chamberlain and to enlarge it more if possible." (52)

On 21st January, the BBC announced that "no efforts to improve Anglo-Italian relations were at all contemplated". This announcement upset Dino Grandi and Chamberlain told Ball to arrange for the story to be refuted. Under pressure from Ball, the following evening the BBC declared that the story had been inaccurate. Ball told newspaper editors that "Chamberlain had spoken firmly to Eden, told him to to toe the line, and instructed him to unearth the original source of the story." (53)

Eden wrote to Chamberlain on 8th February, 1938, that this diplomacy "recreates in Mussolini's mind the impression that he can divide us and he will be the less ready to pay attention to what I have to say to Grandi... Rome was already giving out the impression from that interview that we are courting her, with the purpose, no doubt, of showing Berlin how worth courting she is... This was exactly the hand which mussolini always likes to play and plays with so much skill when he gets a chance. I do not think we should let him." (54)

Christopher Andrew, the author of Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1986) has pointed out that "Ball and Dingli acted intermittently as a secret channel of communication between the prime minister and Count Grandi, the Italian ambassador. On occasion Ball saw Grandi and Dingli saw Chamberlain. Precisely what these backstairs intrigues amounted to remains obscure... Dingli's unpublished memoirs doubtless exaggerate his own role. Ball's own version of events, on the other hand, probably underrates the extent of his secret dealings." (55)

Major Ball continued to work on persuading the media to report favourably on Chamberlain's appeasement policy. It was also important to use the media to undermine those who were opposing this policy. Ball told Count Dino Grandi that his publicity campaign was running at "full blast", and he was delighted to hear that "every possible persuasion was being placed on the Press to conform to the desired object of reversing public opinion about Italy." (56)

An article that appeared in The Daily Mail especially upset the Foreign Secretary: "I am able to state authoritatively that the British Government is eager to press forward new negotiations with Italy with least possible delay. Count Grandi, the Italian Ambassador, is to see Mr. Eden as the Foreign Office today. It is felt in political quarters that already there has been far too much delay in seeking a solution of the differences between Britain and Italy." It added that full legal recognition of Abyssinia would be conceded "as part of a general settlement". (57)

Eden was furious when he read the article as it had "all the hallmarks of authoritative inspiration". (58) Eden asked about this but Chamberlain "flatly denied any responsibility - a barefaced lie." Oliver Harvey, a civil servant working in the Foreign Office correctly discovered the truth: "A curious story reaches me that press campaign about Italy was given out by Sir Joseph Ball at Conservative Head Office, not from No. 10. By whose authority I wonder." In fact, the story was authorized by Chamberlain. (59)

Some newspapers contained stories about the conflict between Chamberlain and Eden. Major Ball persuaded the Sunday Times to run an article denying a disagreement over foreign policy: "There is no truth in the stories published yesterday of acute differences between the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary and of a consequent Ministerial crisis. Though the reports vary in scope and detail, they agree in representing Mr. Chamberlain as the adventurous spirit in foreign policy and Mr Eden as the advocate of more cautious and slower action. I have the highest authority for saying that there is not a word of truth in all this. The Prime Minister and Mr. Eden are in complete agreement." (60)

Resignation of Anthony Eden

Neville Chamberlain felt he could no longer trust Anthony Eden and Major Ball was asked to have the telephones of Eden and his supporters tapped. (61) A couple of years later, Ronald Tree met Ball: "During the war, I came across Sir Joseph Ball at the Ministry of Information, a dislikeable man with an unenviable reputation for doing some of Chamberlain's 'behind-the-scenes' work... he had the gall to tell me that he himself had been responsible for having my telephone tapped." (62)

Ball with the support of MI5 gathered information on the contacts and financial arrangements of Eden and fellow anti-appeasement MPs. (63) Ball also spread the rumour amongst his newspaper friends that Eden was very ill and that he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Ball suggested that Eden might resign so that he could take a three month holiday from politics. (64)

Chamberlain regularly had lunch with the parliamentary lobby journalists at the St Stephen's Club at Westminster. The press office at Number 10 and the Foreign Office News Department worked to see that the government view of foreign policy predominated, and that there was as little debate of the alternatives as possible. Major Ball acted "as a private agent for Chamberlain. Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Deputy Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs believed that Ball was probably encouraging press articles supporting Chamberlain's foreign policy. (65)

Eden made it clear to the prime minister that he was unwilling to force President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia, to make concessions. William Strang, a senior figure in the Foreign Office, also urged caution over these negotiations: "Even if it were in our interest to strike a bargain with Germany, it would in present circumstances be impossible to do so. Public sentiment here and our existing international obligations are all against it." (66)

In February, 1938, Adolf Hitler sacked the moderate Konstantin von Neurath as Foreign Minister, and replaced him with the hard-line, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Eden argued that this move made it even more difficult to get an agreement with Hitler. He was also opposed to further negotiations with Benito Mussolini about withdrawing from its involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Eden stated that he completely "mistrusted" the Italian leader. (67)

At a Cabinet meeting Chamberlain made it clear that he was unwilling to back down over the issue. Anthony Eden resigned on 20th February 1938. He told the House of Commons the following day: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world." (68)

Ball persuaded the BBC to relegate Eden's resignation to the second story on the evenings bulletins and to say nothing at all about Germany or Italy. The Daily Mail reported: "The country will be relieved to learn that Mr.Eden resigned from the Government last night. Mr. Eden's policy during his two years as Foreign Secretary has produced uncertainty at home and bewilderment abroad. The Daily Mail has never seen eye to eye with him. It is to be hoped that in his future political career he will profit by his experiences and mistakes. Above all, the country is fortunate in having a Prime Minister to whom it can give its fullest confidence - a statesman who handles the nation's affairs, both domestic and foreign, with realism and sound common sense. Health reasons have played their part. One of Mr. Eden's colleagues said to me last night: 'Mr. Eden was overwrought this weekend, and there is no doubt that his condition was the culmination of months of strain and hardwork' ". (69)

The Evening Standard, the Daily Express and the Daily Telegraph all supported Chamberlain against Eden. (70) The Times claimed that "his policy of appeasement, which is also the policy of peace." (71) The Manchester Guardian, not under the control of Major Ball, noted that although a resignation of this kind might have precipitated a major government crisis, the press had "preserved a unity of silence that could hardly be bettered in a totalitarian state." (72)

Ball now attempted to undermine Eden by suggesting he was a homosexual and that while he was at university he had attempted to seduce Eddie Gathorne-Hardy. Ball also pointed out that most of his close friends were bachelors or well-known bi-sexuals (Robert Boothby, Ronald Cartland, Harold Nicolson, Harry Crookshank, Jack Macnamara, Jim Thomas, Noel Coward). As a result of these relationships his marriage to Beatrice Beckett was in difficulty and she was having affairs with other men. (73)

Most newspapers backed Chamberlain, while Eden's principal supporters were the Labour Party friendly Daily Herald and the Liberal Party inclined News Chronicle. Despite this Eden was able to attract sizeable support in the country, despite the Government's manipulation of the media. The cheering crowds outside Eden's London home reflected the reaction of many people. According to an opinion poll conducted that month by the British Institute of Public Opinion, fully 71 per cent thought Eden was right to resign, while only 19 per cent thought he should have stayed on. When asked whether they favoured "Mr Chamberlain's foreign policy", only 26 per cent said that they did, against 58 per cent who did not. (74)

In a debate in the House of Commons, the Tory MP, Ronald Cartland defended Eden against the smear campaign organised by Major Ball. He claimed it was wrong for The Times to suggest that Eden had resigned because of ill-health. Quite the contrary, he argued, Eden had taken the decision to resign "in the full possession of his powers and faculties, and... he had never been better in health since he went to the Foreign Office." Cartland added that Neville Chamberlain was "employing methods, which are not in keeping with our traditions and which, even if they are successful, must spoil our good name." (75)

Cartland admitted that he could not support Chamberlain's policy of appeasement and at the end of the debate he joined twenty other Tory MPs in abstaining. This included Anthony Eden, Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan, Brendan Bracken, Edward Spears, Jack Macnamara, Jim Thomas, Ronald Tree, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, Paul Emrys-Evans and Vyvyan Adams. A junior member of the government, Robert Bernays, Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, was tempted to resign but as he was paid £1,500 in addition to the £600 he received as an MP, the equivalent in 2020 prices to an additional £100,000 a year, he felt he could not afford to make this decision. (76)

Appeasement

Major Ball acted as Chamberlain's go-between with the Secret Services and conducted highly secret negotiations for the "appeasement" of Adolf Hitler. Ball was also closely associated with Arthur Charles Wellesley, 5th Duke of Wellington, who held extreme right-wing opinions and was sympathetic to the Nazi Party and was President of the Nordic League, which was a leading anti-semitic organisation and a member of the secret society called the Right Club. On 26th September 1938, Wellington's nephew, Gerald Wellesley, placed Radio Luxembourg at Ball's disposal. Ball shared the radio station with MI6's Section D, which had been put in charge of "political warfare". (77)

Ball also used The Truth to attack those politicians and newspapers complaining about how Adolf Hitler was imprisoning members of the German Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the German Communist Party (KPD). It argued that "Germany's domestic affairs are her own business." (78) The magazine described Hitler in glowing terms at the 1937 Nuremberg Rally: "Today he looks ten years younger than he did four years ago, when he was a tired, worn and harassed man. Now he is fresh-complexioned, often smiling, the worried expression replaced by one of quiet confidence." (79)

The Truth also poured scorn on the number of stories of atrocities against Jews in Nazi Germany. and claimed that anti-Semitism had "weakened of late". (80) The following month the journal suggested that if anti-Semitism ever assumed an uglier aspect in Britain, it would be "the Jews" own fault, because although there were just 350,000 Jews in Britain at the time "this is difficult to credit when one walks through the West End on a Saturday night." It then added, without offering a shred of evidence that it was "no exaggeration to say that of every ten swindles that come under the notice of Truth, an unduly high proportion are operated by Jews." (81)

Ball gained support from right-wing Conservative Party MPs in the House of Commons. Lieutenant Colonel Lambert Ward, who claimed he visited Germany every year denied that thousands were being driven into "hastily-constructed prisons and concentration camps". Ward also said that in his judgement that Germany would never invade Czechoslovakia, but if they did, a third of the Czech Army would desert and join the German Army. He also argued that the British people would not want to go to war to defend the territorial rights of Czechoslovakia. (82)

Major Joseph Ball became an important figure behind the scenes. Hugh Dalton, the Labour Party MP, asked Ronald Cartland who influenced Neville Chamberlain. He replied that none of his colleagues in the Cabinet did, but "there was a queer figure, Sir Joseph Ball, now in the Conservative Head Office, who had been in the Conservative Head Office, who had been in MI5 during the war, in whom the PM had great confidence." (83)

It has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) that Ball prepared notes and drafts for most of Chamberlain's leading foreign affairs speeches. (84) This included the speech given by Chamberlain on 13th December 1938 to the Foreign Press Association. He argued that there were only two possible ways of dealing with the rapidly deteriorating situation in Europe. The first was to decide that war was inevitable and "throw the whole energies of the country into preparation for it". Chamberlain claimed that those who favoured this course were in "a small minority". The second was to make a "prolonged and determined effort to eradicate the possible causes of war" through personal contact and discussion, while attempting to "restore the power of the defence forces". (85)

Ball began a smear campaign against those members of the Conservative Party who opposed appeasement. Ball told sympathetic journalists that they were either gay or bi-sexual and gave them the derisory term "the glamour boys". Ball told the journalist Charles Graves, that these MPs that included Anthony Eden, Harold Nicolson, Ronald Cartland, Robert Boothby, Jack Macnamara and Jim Thomas, and "they are viewed with some suspicion by the party heads" and were providing a "smokescreen" for Winston Churchill. (86)

Ball made attempts to persuade local constituency associations to de-select rebel Conservative Party MPs. The first victim was Katharine Stewart-Murray, the Duchess of Atholl, who had been MP for Kinross and West Perthshire since 1923. As well as being a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler she also campaigned against the government's policy of Non-Intervention in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1937, Stewart-Murray, Eleanor Rathbone and Ellen Wilkinson travelled to Spain on a fact-finding mission. The party visited Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia and observed the havoc being caused by the Luftwaffe. In May 1937 Atholl joined with Charlotte Haldane, Eleanor Rathbone, Ellen Wilkinson and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades. (87)

James Stuart, deputy chief whip, and the MP for Moray and Nairn, was placed in charge of the plot to oust Stewart-Murray and organised a vote of no confidence in her by her local party. She responded by resigning and prompted a by-election. Stewart-Murray stood as an Independent against the Conservative Party candidate, William McNair Snadden. She asked Winston Churchill to speak for her but he refused as he feared being deselected by his local party. Robert Boothby responded in the same way. (88)

Freida Stewart was one of those who helped her during the campaign: "Her Grace was very calm and dignified under the strain, which must have been considerable; she had never been seriously opposed before in the feudal area, and the challenge was for her as much personal as political. In fact it was not. The challenge was one of principle against a whole party-political machine; and the Tories were determined that they were not going to be put in their place by one dissident individual, whatever her title. The Perthshire Conservatives rallied as never before to the true blue flag, and made sure their labourers and employers did the same. their cars were everywhere, taking farm workers to the polls, with the hidden implication that they must vote the conformist ticket or else." (89)

According to Duncan Sutherland: "Fifty Conservative MPs travelled north to warn that a vote for the duchess was a vote for war, and in a more sinister twist local landowners were alleged to have offered their tenants bonuses - or threats - on the understanding that they vote against her. These various factors contributed to her narrow defeat by a Conservative opponent in a two-way contest. Subsequent events in Europe vindicated her position, and would have saved her political career had she remained in parliament a few months longer, but after Churchill assumed the Conservative leadership in 1940 she abandoned plans to return as an independent MP for the Scottish Universities." (90)

In 1939 Major Ball launched a smear campaign against Winston Churchill in an effort to get him de-selected in Epping. Churchill defended his views on appeasement at a meeting in the town: "What is the value of our Parliamentary institutions, and how can our Parliamentary doctrines survive, if constituencies tried to return only tame, docile, and subservient members who tried to stamp out every form of independent judgement? I have been out of office now for ten years, but I am more contented with the work I have done in these last five years as an Independent Conservative than of any other part of my public life." (91)

Churchill and other anti-appeasement figures in the Tory Party, including Anthony Eden, Harold Nicolson, Ronald Cartland, Robert Boothby, Jack Macnamara and Jim Thomas were described to journalists as being "warmongers". As a result when there was a debate on appeasement on 2nd August 1939, only forty Tory MPs abstained and none were willing to vote with the Labour Party on this issue. (92)

Ball continued to monitor Churchill and the other rebels and arranged for their phones to be taped. Tim Bouverie, author of Appeasing Hitler: Chamberlain, Churchill and the Road to War (2020) says almost all MPs who opposed Neville Chamberlain came under huge amounts of pressure. "The whips were incredibly powerful in the 1930s," he says. "The threat of de-selection certainly hung over those who refused to toe the line... And Chamberlain was more than prepared to whip up local Conservative Associations against anti-appeasement MPs." (93)

In the aftermath of Munich Agreement, Major Ball dismantled the Foreign Office News Department, making 10 Downing Street the sole repository for government news. Another important figure was George Steward, Downing Street's chief press liaison officer who, MI5 discovered, had told an official at the German Embassy that Britain would "give Germany everything she asks for the next year". (94)

Ball urged Chamberlain to make use of his popularity by calling a snap election. His cabinet colleagues warned against this fearing that during the campaign Hitler would break the promises he made at Munich. Lord Halifax thought an election would be far too risky and urged Chamberlain to form a government of national unity. Halifax believed this government should include Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden and other critics of appeasement. (95)

In all the eight by-elections that followed the Munich Agreement, the Conservative Party suffered a fall in its support. Major Ball told Chamberlain at the end of November, 1938: "The outlook is far less promising than it was a few months ago, and there are a large number of seats held by only small majorities, so that only a small turnover of votes would defeat the Government." Ball advised the election should be postponed. (96)

Major George Ball and Archibald Ramsay

Major Ball was also close to the right-wing politician, Archibald Ramsay. In the House of Commons Ramsay was one of the leading anti-Semites in the Conservative Party and became convinced that "atheism, agnosticism, communism and Judaism were all wrapped up in a single conspiracy theory". (97) Ramsay became convinced by 1938 that the Russian Revolution and the Spanish Popular Front Government "were part and parcel of the same Plan, secretly operated and controlled by World Jewry." (98)

Ramsay believed that the anti-appeasement newspapers like the Daily Mirror were run and owned by Jews. He claimed that Jews were involved in the "manipulation and control of news for their own ends" and were attempting to "thrust the country into a war". At the end of the debate on Ramsay's Companies Act Amendment Bill with the support of Conservative Party MPs, it was passed 151 to 104. (99) A few days later, Ball's The Truth supported Ramsay's claim that the newspaper was "to be held up as a typical example of the manner in which Jews debauch the minds and standards of a community." (100)

In May 1939 Ramsay founded a secret society called the Right Club. This was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. Or in the leader's words of "co-ordinating the work of all the patriotic societies". In his autobiography, The Nameless War, Ramsay argued: "The main object of the Right Club was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry, in the light of the evidence which came into my possession in 1938. Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence, and the character of our membership and meetings were strictly in keeping with this objective." (101)

Ball was probably a member of the Right Club but it was a highly secret organisation and when the membership book was found after the war most used codenames. Those identified included William Joyce, Anna Wolkoff, Joan Miller, Norah Briscoe, Molly Hiscox, A. K. Chesterton, Francis Yeats-Brown, E. H. Cole, David Freeman-Mitford (2nd Baron Redesdale), Arthur Charles Wellesley (5th Duke of Wellington), Aubrey Lees, John Stourton, Thomas Hunter, Samuel Chapman, Ernest Bennett, Charles Kerr, John MacKie, James Edmondson, Mavis Tate, Marquess of Graham, Margaret Bothamley, Princess Evelyn Blücher and Prince Turka Galitzine. (102)

Major Ball used his The Truth journal to attack prominent Jews who were opposed to appeasement. The publisher, Victor Gollancz, a supporter of the Labour Party, was one of Ball's main targets: "if we set aside the ideological passions of Mr Gollancz and his tribe in the tents of Bloomsbury, the truth is that no appreciable section of British opinion desires to re-conquer Berlin for the Jews or see the Vistula run red with British blood." (103)

Several times during 1939, Major Ball, acting on behalf of Neville Chamberlain, arranged for the former Conservative MP for Basingstoke, Henry Drummond-Wolff to take part in secret peace talks with senior figures in Nazi Germany. In January, he met with Adolf Hitler who said he was particularly anxious to obtain trade preferences for Germany and a return of the colonies. In May, Drummond-Wolff met Hermann Göring and Walther Hewel where they discussed the problem of Danzing and the Polish Corridor. (104)

Leslie Hore-Belisha

Major Ball and other anti-Semitic members of the party were constant critics of the Jewish minister Leslie Hore-Belisha. As Tom Bower pointed out Ball was "a racist and arch-appeaser". (105) The Tory MP, Edward Doran, taunted him by asking the number and nationality of all "money-lenders" registered in the country and claiming that there were 3,000 fraudulent bankrupts in the country, who were "mainly alien Jews" (106) Harry Chips Channon wrote in his diary that Hore-Belisha was "an oily man, half a Jew, an opportunist, with the Semitic flair for publicity". (107)

In the House of Commons, the Tory Archibald Ramsay, was the main critic of having Jews in the government. In 1938 he began a campaign to have Hore-Belisha sacked as Secretary of War. In one speech on 27th April he warned that because he was a Jew Hore-Belisha "will lead us to war with our blood-brothers of the Nordic race in order to make way for a Bolshevised Europe." (108)

Hore-Belisha had a poor relationship with General John Gort, Chief of the Imperial General Staff. By the outbreak of the Second World War the two men were not on speaking terms. General Henry Pownall, the chief of staff to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), reckoned that it was inevitable that General Gort should fall out with Hore-Belisha. After all, the former was "a great gentleman", while the latter was "an obscure, shallow-brained, charlatan, political Jewboy." (109) Chamberlain suggested to Lord Halifax that Hore-Belisha should be moved from Secretary of State for War to Minister of Information. Halifax replied that "Jew control of our propaganda would be a major disaster". (110)

After the outbreak of the Second World War, the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, told King George VI that "as I told him repeatedly before, there existed a strong prejudice against him (Hore-Belisha) for which I could not hold him altogether blameless." (111) On 4th January, 1940, Chamberlain offered him the post of president of the Board of Trade. As it was a demotion and meant he would be outside the War Cabinet, he resigned. Some newspapers such as the Daily Mirror criticised Chamberlain's decision to remove a talented minister. (112)

Henry Newnham, writing in The Truth supported Chamberlain's decision and attempted to completely destroy his political career. He described "Mr Belisha's resignation is a minor episode because he is a minor man whose most conspicuous talent is for getting his photograph into the newspapers." Newnham blamed the "hysteria" surrounding his resignation on "newspapers controlled by Mr Belisha's co-religionists" and the "racial sympathy" he had elicited. (113) The following week Newnham claimed the "Daily Mirror came from the Jew-controlled sink of Fleet Street". Both these editions were sent unsolicited to the homes of all MPs and peers and a large number of journalists and senior civil servants. (114)

Nancy Astor also started the unfounded rumour that Hore-Belisha had been sacked because he had been making money out of army contracts. (115) The historian, Tim Bouverie, claims these stories were part of an orchestrated campaign against Hore-Belisha. He quotes Hore-Belisha as saying: "The Conservative party machine is even stronger than the Nazi party machine. It may have a different aim, but it is similarly callous and ruthless." (116)

Loss of Political Power

In a debate in the House of Commons on 7th May, 1940, Admiral Roger Keyes, the Conservative Party MP for Portsmouth North, attacked the government's military strategy including the role played by Winston Churchill as First Lord of Admiralty: "I came to the House of Commons to-day in uniform for the first time because I wish to speak for some officers and men of the fighting, sea-going Navy who are very unhappy. I want to make it perfectly clear that it is not their fault that the German warships and transports which forced their way into Norwegian ports by treachery were not followed in and destroyed as they were at Narvik. It is not the fault of those for whom I speak that the enemy have been left in undisputable possession of vulnerable ports and aerodromes for nearly a month, have been given time to pour in reinforcements by sea and air, to land tanks, heavy artillery and mechanised transport, and have been given time to develop the air offensive which has had such a devastating effect on the morale of Whitehall. If they had been more courageously and offensively employed they might have done much to prevent these unhappy happenings and much to influence unfriendly neutrals." He then went on to compare the operation with Churchill's failure at Gallipoli. (117)

Leo Amery, another Tory MP, argued in the House of Commons: "Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peace-time statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory." Looking at Chamberlain he then went onto quote what Oliver Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go." (118)

The following day, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party demanded a vote of no confidence in Chamberlain. The 77 year-old David Lloyd George, was one of those MPs who called on the prime minister to resign. The government defeated the Labour motion by 281 to 200 votes. But the abstention of 134 Tory MPs indicated the extent to which the government had haemorrhaged authority. It was clear that drastic changes were essential if the government was to restore its authority. Chamberlain invited Attlee to join a National Government but he refused and said he would only accept if the prime minister resigned. (119)

Chamberlain told King George VI that he had no choice but to resign. In his diary he wrote: "The Amerys, Duff Coopers, and their lot are consciously, or unconsciously, swayed by a sense of frustration because they can only look on, and finally the personal dislike of Simon and Hoare had reached a pitch which I find it difficult to understand, but which undoubtedly had a great deal to do with the rebellion. A number of those who voted against the government have since either told me, or written to me to say, that they had nothing against me except that I had the wrong people in my team." (120)

The King and Chamberlain wanted Lord Halifax to become prime minister. Halifax had the support of some Labour MPs like Hugh Dalton and Herbert Morrison, but not Attlee who wanted Churchill. The King attempted to insist on Halifax but eventually he agreed to ask Winston Churchill to become prime minister. As Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) pointed out: "It was perhaps the crowning irony of his career that he should become Prime Minister because of the need to bring the Labour Party, which had so far only formed two minority governments, into a national coalition. One of the main motivating forces of his political life in the previous twenty years was his outright opposition to the claims of Labour and the trade unions, reflected in his often expressed belief that not only were they unfit to govern the country but that they were engaged in a campaign to subvert its political, economic and social institutions." (121)

After Chamberlain resigned Ball lost his power in the Conservative Party. However, he kept control over The Truth journal where it continued with its rabid anti-Semitism. In an article published on 6th August, 1940, Henry Newnham wrote: "I was reading early this week the official list of our casualties during the Battle of France. I noticed among the names of other members of the 'ruling class' those of the Duke of Northumberland, the Earl of Aylesford, the Earl of Coventry, Lord Frederick Cambridge - all killed in action. I did not notice any names like Gollancz, Laski, and Strauss, from which I draw the conclusion that what happened in the last war is being repeated in this. The ancient families of Britain - the hated ruling class of the Left Wing diatribes - are sacrificing their bravest and best to keep the Strausses safe in their homes, which in the last war they did not don uniforms to defend." (122)

George Strauss objected to the claim that he was a coward for not fighting for his country during the First World War. As he pointed out he was too young to fight in the war and he won substantial damages from the journal. Josiah Wedgwood, the Labour MP suggested to Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary, that The Truth should be banned because it had been a long-term supporter of the British Union of Fascists and continued to express anti-Semitic views. He added that it would be "a Quisling paper if the Germans ever come here." As the journal was still being funded by the Conservative Party it was impossible for Morrison to take action against it. (123)

According to Chapman Pincher, the author of Their Trade is Treachery (1981) Major Ball was involved in the reorganization of the Security Service after the departure of Vernon Kell in the summer of 1940. This included the recruitment of his old friend Guy Burgess into MI5. Burgess posed as a right-wing Conservative but was really a Soviet spy and part of the network that included Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean and James Klugmann. "Burgess used this friendly contact to infiltrate his way into MI5." (124)

After the end of the war Ball entered the world of business, and became chairman of Henderson's Transvaal Estates and five subsidiary companies, and also of Lake View and Star. He was a director of Consolidated Goldfields of South Africa and of the Beaumont property trust. Between 1947 and 1953 Ball was chairman of the Hampshire rivers catchment board. (125)

Major George Joseph Ball died on 10th July 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009)

Despite the success with which former members of the Service on Kell's reserve list had been reintegrated during the General Strike, the fortunes of MI5 were at a low ebb. Lack of resources led at the end of 1926 to the loss of one of M15's ablest officers, Major (later Sir) Joseph Ball, the head of B Branch, which during the post-war cutbacks had taken over responsibility for investigations. Ball had joined MI5 in July 1915 after a decade at Scotland Yard, dealing mainly with aliens. He was also a barrister, having passed top of the Bar final exams, and spent much of the war questioning prisoners, internees, suspects and aliens." Ball's decision to leave MI5 at the end of 1926 seems to have been related to dissatisfaction over pay and prospects. He had complained in 1925 that his pay and pension would both have been higher had he remained at New Scotland Yard." In March 1927 the Conservative Party chairman, J. C. C. (later Viscount) Davidson, recruited Ball to help run "a little intelligence service of our own", distinct from the main Central Office organization... In 1930 Ball was appointed first director of the new Conservative Research Department, becoming a confidant of the future Party leader Neville Chamberlain.

(2) Henry Newnham, The Truth (6th August, 1940)

I was reading early this week the official list of our casualties during the Battle of France. I noticed among the names of other members of the 'ruling class' those of the Duke of Northumberland, the Earl of Aylesford, the Earl of Coventry, Lord Frederick Cambridge - all killed in action. I did not notice any names like Gollancz, Laski, and Strauss, from which I draw the conclusion that what happened in the last war is being repeated in this. The ancient families of Britain - the hated ruling class of the Left Wing diatribes - are sacrificing their bravest and best to keep the Strausses safe in their homes, which in the last war they did not don uniforms to defend.

(3) Ken Livingstone, speech in the House of Commons (10th January, 1996)

We all know about the Zinoviev letter, which led to the downfall of the first Labour Government in 1924. It is now believed to have been produced by two Russian emigres who were working in Berlin. They passed the forgery to an MI5 officer, Donald Thurn. Once in the hands of MI5, senior officials realised that its details of an alleged communist plot would be a devastating blow to the Labour Government in the closing days of the election campaign. MI5 leaked the letter to a Tory Member of Parliament and former intelligence officer, Sir Reginald Hall. It also leaked it to Tory central office and the Daily Mail, which obligingly ran it on its front page.

In the run-up to the 1929 election, the links between MI5 and the Tory party were renewed. The head of MI5's investigation branch, Major Joseph Ball, was employed by Conservative central office to run agents inside the Labour party. After the election, Ball was rewarded with the directorship of the Tories' research department.

(4) John Campbell Davidson, Memoirs of a Conservative (1969)

We had agents (ran by Joseph Ball) in certain key centres and we also had agents actually in the Labour Party Headquarters, with the result that we got their reports on political feeling in the country as well as our own. We also got advance "pulls" of their literature. This we arranged with Odhams Press, who did most of the Labour Party printing, with the result that we frequently received copies of their leaflets and pamphlets before they reached Transport House (the Labour HQ). This was of enormous value to us because we were able to study the Labour Party policy in advance, and in the case of leaflets we could produce a reply to appear simultaneously with their production.

(5) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009)

Allegedly dispatched by Zinoviev and two other members of the Comintern Executive Committee on 15 September 1924, the letter instructed the CPGB leadership to put pressure on their sympathizers in the Labour Party, to "strain every nerve" for the ratification of the recent treaty concluded by MacDonald's government with the Soviet Union, to intensify "agitation-propaganda work in the armed forces", and generally to prepare for the coming of the British revolution. On 9 October SIS forwarded copies to the Foreign Office, MIS, Scotland Yard and the service ministries, together with an ill-founded assurance that "the authenticity is undoubted". The unauthorized publication of the letter in the Conservative Daily Mail on 25 October in the final week of the election campaign turned it into what MacDonald called a "political bomb", which those responsible intended to sabotage Labour's prospects of victory by suggesting that it was susceptible to Communist pressure.

The call in the Zinoviev letter for the CPGB to engage in 'agitation-propaganda work in the armed forces" placed it squarely within MI5's sphere of action. Like others familiar with Comintern communications and Soviet intercepts, Kell was not surprised by the letter's contents, believing it "contained nothing new or different from the (known) intentions and propaganda of the USSR." He had seen similar statements in authentic intercepted correspondence from Comintern to the CPGB and the National Minority Movement (the Communist-led trade union organization), and is likely - at least initially - to have had no difficulty in accepting SIS's assurance that the Zinoviev letter was genuine. The assurance, however, should never have been given. Outrageously, Desmond Morton of SIS told Sir Eyre Crowe, PUS at the Foreign Office, that one of Sir George Mahgill's agents, "Jim Finney", who had penetrated the CPGB, had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter. On the basis of that information, Crowe had told MacDonald that he had heard on "absolutely reliable authority" that the letter had been discussed by the Party leadership. In reality, Finney's report of a discussion by the CPGB Executive made no mention of any letter from Moscow. MI5's own sources failed to corroborate SIS's claim that the letter had been received and discussed by the CPGB leadership - unsurprisingly, since the letter had never in fact been sent.

MI5 had little to do with the official handling of the Zinoviev letter, apart from distributing copies to army commands on 22 October 1924, no doubt to alert them to its call for subversion in the armed forces. The possible unofficial role of a few MI5 officers past and present in publicizing the Zinoviev letter with the aim of ensuring Labour's defeat at the polls remains a murky area on which surviving Security Service archives shed little light. Other sources, however, provide some clues. A wartime MI5 officer, Donald Im Thurn ("recreations: golf, football, cricket, hockey, fencing"), who had served in MI5 from December 1917 to June 1919, made strenuous attempts to ensure the publication of the Zinoviev letter and may well have alerted the Mail and Conservative Central Office to its existence. Im Thurn later claimed implausibly to have obtained a copy of the letter from a business friend with Communist contacts who subsequently had to flee to "a place of safety" because his life was in danger. This unlikely tale was probably invented to avoid compromising his intelligence contacts. After Im Thurn left the Service for the City in 1919, he continued to lunch regularly in the grill-room of the Hyde Park Hotel with Major William Alexander of B Branch (an Oxford graduate who had qualified as a barrister before the First World War). Im Thurn was also well acquainted with the Chief of SIS, Admiral Quex Sinclair. Though he was not shown the actual text of the Zinoviev letter before publication, one or more of his intelligence contacts briefed him on its contents. Alexander appears to have informed Im Thurn on 21 October that the text was about to be circulated to army commands. Suspicion also attaches to the role of the head of B Branch, Joseph Ball. Conservative Central Office, with which Ball had close contacts, probably had a copy of the Zinoviev letter by 22 October, three days before publication. Ball's subsequent lack of scruples in using intelligence for party-political advantage while at Central Office in the later 1920's strongly suggests, but does not prove, that he was willing to do so during the election campaign of October 1924. But Ball was not alone. Others involved in the publication of the Zinoviev letter probably included the former DNI, Admiral Blinker Hall, and Lieutenant Colonel Freddie Browning, Cumming's former deputy and a friend of both Hall and the editor of the Mail. Hall and Browning, like Im Thurn, Alexander, Sinclair and Ball, were part of a deeply conservative, strongly patriotic establishment network who were accustomed to sharing state secrets between themselves: "Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion."

Those who conspired together in October 1924 convinced themselves that they were acting in the national interest - to remove from power a government whose susceptibility to Soviet and pro-Soviet pressure made it a threat to national security. Though the Zinoviev letter was not the main cause of the Tory election landslide on 29 October, many politicians on both left and right believed that it was. Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told his rival Lord Rothermere, proprietor of the Daily Mail, that the Mail's "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere immodestly agreed that he had won a hundred seats. Labour leaders were inclined to agree. They felt they had been tricked out of office. And their suspicions seemed to be confirmed when they discovered the part played by Conservative Central Office in the publication of the letter.

(6) Giorgio Peresso, Times of Malta (30th September 2012)

While he acted as legal adviser to the Italian Embassy in London, Dingli was also consultant to the War Office in London as from 1922. This ambivalent position would earn him the reputation of running with the hares and hunting with the hounds – which would cost him dearly at the end of his life.

On being told by Sir Herbert Creedy, the permanent under-secretary at the War Office (1920-1939), that his role with another government was incompatible with the War Office assignment, Dingli chose to work for the Italians.

He cherished British institutions. His membership of the Carlton Club, where the British Empire's movers and shakers met was testament to his Britishness. But he was also an ardent Italophile at heart.

Dingli's fame reached its peak after Sir Neville Chamberlain became prime minister in May 1937. Chamberlain believed that since both Britain's economy and its military defences were weak, the best bet was appeasement to the Nazi-Fascist regimes to avoid war.

His Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, believed that appeasement facilitated the possibility of war. Nevertheless, the British prime minister was determined to reach an accommodation with the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini.

Chamberlain not only had misgivings about his Foreign Office but also wanted to influence British foreign policy to suit his own abilities and judgement.

He bypassed the British Embassy in Rome in his approaches to Mussolini, using such conduits as Lady Ivy Chamberlain, widow of his brother Austen. He therefore preferred to rely on a personal friend, Major Ball, the head of the Conservative Research Office.

Ball was described by Michael Dobbs, the Conservative politician and bestselling author, as Chamberlain's thug and political twister. Ball was as ruthless a schemer as could be.

He found in his old Gray's Inn colleague Dingli a source of valuable contacts linking him to a circle which would lead to the Duce himself.

On July 12, 1937, the Italian Ambassador in London, Count Dino Grandi, wrote a rather long letter to his Foreign Minister in Rome, Count Galeazzo Ciano, informing him of Dingli's imminent secret mission to Rome.

He described Dingli as the "legal adviser of this embassy and a Maltese patriot who has always stuck to the cause of Malta's italianità, connected to the Carlton Club for many years, who was approached by Sir Joseph Ball, chief policy adviser to the Conservative Party and a very close friend of Neville Chamberlain".

Ball had given Dingli a long speech on Chamberlain's sincere desire to come to a complete understanding with Italy, working out cordial relations before initiating official steps through the Foreign Office. Grandi, however, revealed his secret agenda to Ciano: to sow discord between Chamberlain and Eden...

Dingli was simply used to divert attention from Italy's real intentions. What interested the Italians most was to exploit the divergences between Chamberlain and his Foreign Minister, Eden. In fact, Eden resigned and the Anglophile Grandi was replaced by a more dogmatic Fascist, Giuseppe Bastianini.

Still, Grandi, after he became Minister of Justice, called his friend Dingli to Rome. From now on, the channel was to operate solely through him and Ball. Grandi reiterated that Germany was determined to go to war. He therefore advised the Maltese diplomat to find some cover for his frequent trips to Rome. Dingli chose that of a British film agent.

While Hitler was rolling up the map of Europe, Chamberlain as late as April, 1940, was making a last-ditch attempt to mollify Mussolini.

Dingli's role did not go unnoticed by Colonel Liddell, a high-ranking intelligence officer. Dingli's reputation as a man with powerful links with Rome had not waned in spite of a deteriorating geo-political situation as Dingli was reputed to have supplied Ball with details of secret clauses in the military alliance between Italy and Germany.

The chief of British security services, Major-General Sir Stewart Menzies, snubbed Liddell for grilling the Maltese lawyer before his trip to Rome. Ciano recorded in his diary that Dingli impressed him as being of rather secondary importance.

The die was cast. Italy invaded Albania on Good Friday, April 7, 1940. At that time, Ball met Dingli, telling him that "his master" was extremely angry. This dealt a death-blow to appeasement and Dingli's links. Chamberlain's days were numbered.

After Chamberlain's resignation on May 10, 1940, Ball survived, but Dingli's pro-Italian inclinations turned him into an enemy.

During the war, Dingli worked in a business in Bristol. Ball believed that his standing was hostage to Dingli's scrupulous record of his secret diplomacy, as potential sensational disclosures about pre-war negotiations involving Ball could endanger his reputation.

While Europe was celebrating Victory Day, the former diplomat became a victim of Ball's intrigues, implicating Dingli in wrongdoings in business. Dingli died unexpectedly, probably murdered, on May 29, 1945.

Two days later, MI5, with which, according to some accounts (challenged by some historians), Dingli was previously associated, the British security agents seized his diary.

Lord Avon recorded almost as an afterthought in his memoirs that the full story will probably never be known. What Ball and the secret service did not know was that there was a duplicate copy of the diary. In 1950, when the coast was clear, Dingli's widow went to Lisbon where Grandi was living in exile and handed the duplicate copy.