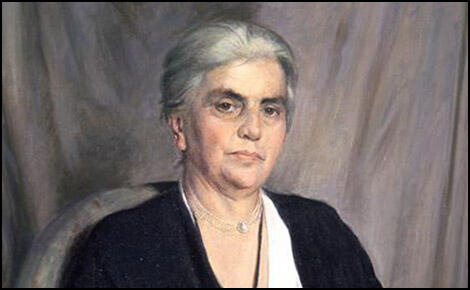

Eleanor Rathbone

Eleanor Rathbone was born in London on 12th May 1872. Her father, William Rathbone, a prosperous shipowner, came from a Quaker and Unitarian background. A supporter of the Liberal Party, William Rathbone served in the House of Commons from 1869 to 1895.

Rathbone was educated at home by a governess and private tutors before entering Somerville College, Oxford, in 1893. At university Rathbone became involved in the struggle to obtain women the vote and eventually became a leading figure in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

After leaving university with a degree in philosophy, Rathbone became secretary of the Women's Industrial Council in Liverpool and was very involved in the organization's campaign against low pay and bad working conditions. In 1909 she became the first woman to be elected to Liverpool City Council and over the next few years argued for improved housing in the city.

Rathbone was elected to the executive committee of the NUWSS and led the opposition to the decision in 1912 to advise all members to campaign for the Labour Party in the general election. The following year she published her first book, The Condition of Widows under the Poor Law (1913).

During the First World War Rathbone established a committee to look into poverty in Britain. Members included Henry N. Brailsford, Maude Royden, Kathleen Courtney, Mary Stocks and Emile Burns. In 1917 the Family Endowment Committee published Equal Pay and the Family. A Proposal for the National Endowment of Motherhood (1917). In the pamphlet Rathbone and her colleagues argued for the introduction of family allowances.

On the resignation of Millicent Fawcett in March 1919, Rathbone became president of the National Union for Equal Citizenship. When the 1921 Census was taken, Eleanor Rathbone, was visited by 35-year-old Eva Hubback at her latter's house 'Oakfield', Penny Lane, Toxteth Park, Liverpool, which she shared with Elizabeth Macadam (1871-1948) a university lecturer. Also living at the house was a 39-year-old widow named Annie Farup, described on the census form as Secretary of the Liverpool Women Citizen's Association. Rathbone's household was completed by three female domestic servants.

Eleanor Rathbone continued to campaign for social reform and in 1925 published her important book, The Disinherited Family. The following year the introduction of family allowances became a policy of the Independent Labour Party. However, the idea was rejected by the three major political parties.

In 1929 Rathbone was elected to the House of Commons as the Independent Member for the Combined English Universities. Over the next few years she campaigned against female circumcision in Africa, child marriage in India and forced marriage in Palestine. This included the publication of the book, Child Marriage: The Indian Minotaur (1934).

Rathbone also took a keen interest in foreign policy and was a strong opponent of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1937, Rathbone, Ellen Wilkinson and the Duchess of Atholl travelled to Spain on a fact-finding mission. The party visited Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia and observed the havoc being caused by the Luftwaffe.

In May 1937 Rathbone joined with Charlotte Haldane, Duchess of Atholl, Ellen Wilkinson and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades. Later she helped establish the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief.

Rathbone grew increasingly concerned about Adolf Hitler and his government in Nazi Germany. She totally opposed the British government's policy of appeasement and instead called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. These views were expressed in her book, War Can Be Averted (1937) and were officially supported by Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, David Lloyd George, Hugh Dalton and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

During the Second World War Rathbone continued to campaign for family allowances and in 1940 published The Case for Family Allowances. This became the policy of the Labour Party and her family allowances system was introduced in 1945. However, Rathbone was furious when she discovered that the allowance was to be paid to the father rather than the mother. This negated the feminist implications of the measure and she threatened to vote against the Bill.

Eleanor Rathbone died of a heart-attack on 2nd January 1946.

Primary Sources

(1) Mary Stocks, a member of the Family Endowment Committee, wrote about Rathbone in her book, Eleanor Rathbone (1949)

Eleanor assembled a small committee consisting of seven persons with whom she had discussed the matter and whom she knew to be sympathetic to the idea. Two of them were former colleagues on the N.U.W.S.S. Executive Committee: Kathleen Courtney and Maude Royden; one was a newcomer on the Executive: Mary Stocks. A fourth was H. N. Brailsford, a left-wing author and journalist of international fame on international subjects, but in addition a very active feminist. To them were added Mr. and Mrs. Emile Burns, both good feminists, Socialists and students of economics.

The Committee thus had its roots in the women's suffrage movement, but its personnel was definitely left-wing. With the exception of Eleanor, who neither at that time nor at any other professed adherence to a political party, her six pioneer colleagues were either members of the Labour Party or in sympathy with it. And in view of the fact that their object was to inject a strong dose of social provision into the body politic, this early bias is perhaps understandable.

It deliberated under the shadow of war. In fact the war, or conditions precipitated by the war, had provided it with a starting point for its deliberations. The question of "equal pay for equal work" had become acute, and in one corner of the industrial field women bus conductors had carried through a successful strike for "equal pay." A record of their struggle and the social implications of their victory formed the opening chapter of the statement which the Family Endowment Committee drafted. Following the familiar chain of argument, it recapitulated the case for direct provision for the family, illustrating its progress with statistics assembled under the expert guidance of Emile Burns. From this there emerged a concrete scheme for the payment by the State to all mothers qua mothers of the scale of allowances then in force for the wives of Service men.

(2) In 1919 Eleanor Rathbone played an important role in developing the six major demands of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

1. Equal pay for equal work, involving an open field for women in industry and the professions.

2. An equal standard of sex morals as between men and women, involving a reform of the existing divorce law which condoned adultery by the husband, as well as reform of the laws dealing with solicitation and prostitution.

3. The introduction of legislation to provide pensions for civilian widows with dependent children.

4. The equalization of the franchise and the return to Parliament of women candidates pledged to the equality programme.

5. The legal recognition of mothers as equal guardians with fathers of their children.

6. The opening of the legal profession and the magistracy to women.

(3) Eleanor Rathbone, Presidential Address to the Annual Council of the National Union for Equal Citizenship (1926)

Most of our reforms today require difficult readjustments of a complicated, antiquated structure of case law and statute law. We were backwoodsmen in pre-war days; now we need to be skilled artisans. If we go to the Government saying merely, this or that is wrong, put it right for us, they can bluff us as a lazy builder bluffs an ignorant housewife who asks him to cure her smoky chimney, saying, 'Madam, what you want is impossible; if we did it the house would tumble down.' Our method is to study the faulty structure for ourselves and make our plans, though they may not be exactly the plans which the builder carries out, yet he sees we know too much to be pacified with bluff.

(4) Eleanor Rathbone, speech at Bedford College (29th November 1935)

There is a school of reformers which despises compromise. Suppose they set their affections on the moon. Their way is to go on chanting, 'We want the moon, we want the moon, we want the moon.' The plan which experience taught us was to begin by declaring, 'We want the moon,' but when certain that was unobtainable, to say firmly, 'If you can't give us the moon, give us that particular star, that big one'; if that failed, 'At least let us have that little star, just near the horizon. You know you can reach that one.' And when we got it, from the vantage ground of that little star, we proceeded to grasp at those nearest it. Or, to change the metaphor, there are reformers whose idea of taking a citadel is to march round it blowing trumpets, and when that fails, to batter it with rams, if necessary with their own heads. We sometimes used the battering ram, but if the wall proved too strong for us we withdrew a little and investigated every possible method of overcoming that wall, by climbing over it, or tunnelling under it or perhaps labouring to dislodge a stone at a time, so that just a few invaders could creep through. And we acquired by experience a certain flair which told us when a charge of dynamite would come in useful and when it was better to rely on the methods of the skilled engineer.

Another lesson we learned was the importance of being early in the field. If some legislative change is known to be projected which one wants to influence, it does not do to wait until the authorities have definitely made up their minds as to the form of the change; much less until the Bill is actually drafted and may be difficult to amend without upsetting the balance of its parts. Get at the people responsible, the Minister or, better still, the officials or committees which advise him, while they are still in the stage of welcoming evidence and suggestions rather than of resenting criticism.

(5) After her visit to Spain in April 1937, Eleanor Rathbone wrote to her constituents about the Spanish Civil War.

In these days of defeatism, it is something to have seen a great city full of men and women who throughout a year of privation, terror and suffering have looked death in the face without losing their courage, their complete confidence in the victory of their cause, or even their high spirits. The Civil War had thrown up a great people - great at least in the qualities of courage and devotion to unselfish ends. Think of those men and women, with centuries of oppression behind them, bred in bitter poverty and ignorance, deserted by most of their natural leaders, delivered over defenceless to their enemies by the democracies which should have aided them. Think of them as I saw them last April in Madrid and Valencia, men and women, young and old, without a trace of fear or dejection in their faces though bombs were crashing a few yards away and taking their daily toll of victims, going about their daily business in cheerful serenity, building up a system of social services that would have been a credit to any nation at war, submitting to unaccustomed discipline, composing their party differences, going to the front or sending their men to the front as though to a. fiesta, unstimulated - most of them - by hope of Heaven or fear of Hell, yet willing to leave the golden Spanish sunshine and all the lovely sights and sounds of spring and go into the blackness of death or the greater blackness of cruel captivity without a thought of surrender.

(6) Eleanor Rathbone, letter to Winston Churchill (September, 1938)

Everyone I meet, mostly not of your party, wonders what you are thinking about the Government's attitude and whether you do not favour a more plain-spoken warning to Hitler. Hearing nothing, we are left wondering whether you too believe that our military position is too weak for us to venture on that. Hitherto only the Trades Union Congress and the Labour Party have spoken out in a way calculated to make Hitler believe that England may possibly mean business. If you did feel able to say anything of the same sort and especially if Mr. Eden did so too, I believe it would rally opinion in the country as nothing else would. There is a great longing for leadership and even those who are far apart from you in general politics realize that you are the one man who has combined full realization of the dangers of our military position with belief in collective international action against aggression. And if we fail again, will there ever be another chance?

(7) Eleanor Rathbone, election address (1945)

The earliest risks may arise not from pulverized Germany, but from the relations between ourselves and Russia. As one who has given many proofs of sincere desire for Anglo-Soviet friendship, I am deeply perturbed by signs of the Soviet's intention to take full advantage of the freedom of access and of criticism allowed them by the Western Powers while rigidly excluding all impartial observers, not only from the conquered lands they control, but from Poland, which they professedly desire to see free and independent. Yet we have a special responsibility towards Poland, on whose behalf we entered the war. The London Polish Government may be inordinately ambitious and unrealistic. The offered Curzon Line may be quite good enough. What matters is, as Mr. Churchill put it, whether the Poles are to be 'masters in their own house' or their State 'a mere projection of the Soviet State, forced against their will, by an armed minority, to adopt a Communist or totalitarian system.' It looks as though the latter were Marshal Stalin's intention."

(8) Mary Stocks, Eleanor Rathbone (1949)

The triumph of family allowances involved her in a social event which may or may not have given her pleasure, but which undoubtedly gave pleasure to a wide circle of her friends and fellow workers. On November 13th (1945) they organized a gathering in Grosvenor House: tea to begin with, speeches to follow. It was a distinguished gathering, graced by the presence of the Minister for National Insurance and Sir William (later Lord) Beveridge. Unfortunately, the date happened to coincide with a Parliamentary statement by the Foreign Secretary on Palestine, in which the guest of honour was passionately interested. There was indeed some doubt as to whether Elizabeth would be able to extract her from the House of Commons. However the thing was done, she arrived a little late, and appeared to enjoy meeting old friends, many of them campaigners of the suffrage as well as of the family allowance cause. The speeches which followed, however, appeared to cause her some little embarrassment. In reply to glowing but in fact unexaggerated tributes, she endeavoured to shift the praise on to some of those present.

But here her sense of proportion and of historical accuracy was at fault, for if ever one person was responsible for a major reform, Eleanor was responsible for family allowances. Of course, Plimsoll did not achieve his Plimsoll line in complete isolation. Of course, Belisha did not erect his beacons single-handed and Lansbury could scarcely have constructed his Lido without public support. In a literal sense, Eleanor was right in disclaiming sole responsibility for family allowances. Nevertheless, if there had been no Eleanor it is difficult not to conclude that there would have been no Family Allowance Act in 1945. It was her victory, conceived in her brain, brought to birth by her persistence, shaped by her vehemence.

She herself had no time for such thoughts. The Family Allowance Bill had become an Act. It was not a very good Act. In due course it would certainly have to be amended.

(9) Harold Nicholson and Eleanor Rathbone, The Spectator (11th January 1946)

Her contribution to the legislative assembly was a distinctively feminine contribution. By this I do not mean only that she was at first mainly interested in the improvement of family conditions and in the recognition of the responsible place which women must occupy in the life of the State. I mean that the persistence and the zeal with which she identified herself with her own causes gave a new meaning to, or deprived of all meaning, the facile criticism that 'women approach politics from a personal point of view. She taught the House of Commons that such identification, while intense, could be completely selfless. She added objective ardour to subjective sympathy.

This fusion of ardour with selflessness had another aspect. She was in fact so absolutely selfless that she seemed at moments to be devoid of all self-consciousness. Even her admirers would feel at times that she lacked a sense of occasion and that her appeals and interruptions were intrusive and ill-timed. There were those - especially those who sat upon the Front Bench or were charged with administrative responsibilities - who felt that she relied too much upon the feminine privilege of making herself a nuisance. Again and again have I observed Ministers or Under-Secretaries wince in terror when they observed that familiar figure advancing towards them along the corridors; they would make sudden gestures indicating that they had left some vital document behind them, swing round on their feet, and scurry back to their rooms; or equally suddenly they would engage some passing colleague in passionate conversation, placing a confiding but retentive hand upon his startled shoulder, waiting in trepidation until she had passed by. She was too shrewd not to observe these subterfuges and evasions. Benign and yet menacing, she would stalk through the lobby, one arm weighed with the heavy satchel which contained the papers on family allowances, another arm dragging an even heavier satchel in which were stored the more recent papers about refugees and displaced persons; recalcitrant Ministers would quail before the fire of her magnificent eyes. Yet she was aware that her ardour was apt to create a mood of sales resistance. Again and again she would ask some other member to approach a given Minister on the ground that she herself had tried his patience too far. Yet although in attack she was as undeviating, as relentless and as pertinacious as a flying bomb, in the moment of victory she was amazingly conciliatory. While the battle was on she displayed all the passion of the fanatic; when the enemy yielded, she advanced towards him bearing the olive branch of compromise.

It was not only the feminine qualities of identification, of fanaticism and of persistence which rendered Eleanor Rathbone so formidable. Her position as an independent Member made her immune to the discipline and even to the conventions of party politics. Her hatred of cruelty in any form was matched by an equally passionate contempt for acts of unfairness which were due to inattention, laziness, lack of precise knowledge or ordinary easy going. Her slings were weighted with the pebbles of hard fact and she would hurl these missiles, sometimes rashly, sometimes intemperately, but sometimes with devastating effect.