Zinoviev Letter

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (1)

Members of establishment were appalled by the idea of a Prime Minister who was a socialist. As Gill Bennett pointed out: "It was not just the intelligence community, but more precisely the community of an elite - senior officials in government departments, men in "the City", men in politics, men who controlled the Press - which was narrow, interconnected (sometimes intermarried) and mutually supportive. Many of these men... had been to the same schools and universities, and belonged to the same clubs. Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion." (2)

1924 Labour Government

The most hostile response to the new Labour government was Lord Northcliffe, the owner of several Conservative Party supporting newspapers. The Daily Mail claimed: "The British Labour Party, as it impudently calls itself, is not British at all. It has no right whatever to its name. By its humble acceptance of the domination of the Sozialistische Arbeiter Internationale's authority at Hamburg in May it has become a mere wing of the Bolshevist and Communist organisation on the Continent. It cannot act or think for itself." (3)

Two days after forming the first Labour government Ramsay MacDonald received a note from General Borlass Childs of Special Branch that said "in accordance with custom" a copy was enclosed of his weekly report on revolutionary movements in Britain. MacDonald wrote back that the weekly report would be more useful if it also contained details of the "political activities... of the Fascist movement in this country". Childs wrote back that he had never thought it right to investigate movements which wished to achieve their aims peacefully. In reality, MI5 was already working very closely with the British Fascisti, that had been established in 1923. (4)

Maxwell Knight was the organization's Director of Intelligence. In this role he had responsibility for compiling intelligence dossiers on its enemies; for planning counter-espionage and for establishing and supervising fascist cells operating in the trade union movement. This information was then passed onto Vernon Kell, Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau (MI5). Later Maxwell Knight was placed in charge of B5b, a unit that conducted the monitoring of political subversion. (5)

John Ross Campbell Case

On 25th July 1924, the Worker's Weekly, a newspaper controlled by the Communist Party of Great Britain, published an "Open Letter to the Fighting Forces" that had been written anonymously by Harry Pollitt. The article called on soldiers to "let it be known that, neither in the class war nor in a military war, will you turn your guns on your fellow workers, but instead will line up with your fellow workers in an attack upon the exploiters and capitalists and will use your arms on the side of your own class." (6)

After consultations with the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Attorney General, Sir Patrick Hastings, it was decided to arrest and charge, John Ross Campbell, the editor of the newspaper, with incitement to mutiny. The following day, Hastings had to answer questions in the House of Commons on the case. However, after investigating Campbell in more detail he discovered that he was only acting editor at the time the article was published, he began to have doubts about the success of a prosecution. (7)

The matter was further complicated when James Maxton informed Hastings about Campbell's war record.

In 1914, Campbell was posted to the Clydeside section of the Royal Naval division and served throughout the war. Wounded at Gallipoli, he was permanently disabled at the battle of the Somme, where he was awarded the Military Medal for conspicuous bravery. Hastings was warned about the possible reaction to the idea of a war hero being prosecuted for an article published in a small circulation newspaper. (8)

At a meeting on the morning of the 6th August, Hastings told MacDonald that he thought that "the whole matter could be dropped". MacDonald replied that prosecutions, once entered into, should not be dropped under political pressure". At a Cabinet meeting that evening Hastings revealed that he had a letter from Campbell confirming his temporary editorship. Hastings also added that the case should be withdrawn on the grounds that the article merely commented on the use of troops in industrial disputes. MacDonald agreed with this assessment and agreed the prosecution should be dropped. (9)

On 13th August, 1924, the case was withdrawn. This created a great deal of controversy and MacDonald was accused of being soft on communism. MacDonald, who had a long record of being a strong anti-communist, told King George V: "Nothing would have pleased me better than to have appeared in the witness box, when I might have said some things that might have added a month or two to the sentence." (10)

The Zinoviev Letter

On 10th October 1924, MI5 received a copy of a letter, dated 15th September, sent by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, to Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were asked to take all possible action to ensure the ratification of the Anglo-Soviet Treaties. It then went on to advocate preparation for military insurrection in working-class areas of Britain and for subverting the allegiance in the army and navy. (11)

Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect. (12) Vernon Kell, the head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the letter was genuine. Desmond Morton, who worked for MI6, told Sir Eyre Crowe, at the Foreign Office, that an agent, Jim Finney, who worked for George Makgill, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), had penetrated Comintern and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Morton told Crowe that Finney "had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter". However, Christopher Andrew, who examined all the files concerning the matter, claims that Finney's report of the meeting does not include this information. (13)

Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret. (14) Thomas Marlowe, who worked for the press baron, Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, had a good relationship with Reginald Hall, the Conservative Party MP, for Liverpool West Derby. During the First World War he was director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID) and he leaked the letter to Marlowe, in an effort to bring an end to the Labour government. (15)

The newspaper now contacted the Foreign Office and asked if it was a forgery. Without reference to MacDonald, a senior official told Marlowe it was genuine. The newspaper also received a copy of the letter of protest sent by the British government to the Russian ambassador, denouncing it as a "flagrant breach of undertakings given by the Soviet Government in the course of the negotiations for the Anglo-Soviet Treaties". It was decided not to use this information until closer to the election. (16)

Soviet Union Trade Agreement

David Lloyd George signed a trade agreement with Russia in 1921, but never recognised the Soviet government. On taking office the Labour government entered into talks with Russian officials and eventually recognised the Soviet Union as the de jure government of Russia, in return for the promise that Britain would get payment of money that Tsar Nicholas II had borrowed when he had been in power. (17)

A conference was held in London to discuss these matters. Most newspapers reacted with hostility to these negotiations and warned of the danger of dealing with what they considered to be an "evil regime". in August 1924 a wide-ranging series of treaties was agreed between Britain and Russia. "The most-favoured-nation status was given to the Soviet Union in exchange for concessions to British holders of Czarist bonds, and Britain agreed to recommend a loan to the Soviet government." (18)

Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party, and H. H. Asquith, the leader of the Liberal Party, decided to being the Labour government down over the issue of its relationship with the Soviet Union. On 30th September, the Liberals condemned the recently agreed trade deal. They claimed, unjustly, that Britain had given the Russians what they wanted without resolving the claims of British bondholders who had suffered in the revolution. "MacDonald reacted peevishly to this, accusing them of being unscrupulous and dishonest." (19)

The following day, Conservatives put down a censure motion on the decision to drop the case against John Ross Campbell. The debate took place on 8th October. MacDonald lost the vote by 364 votes to 198. "Labour was brought down, on the Campbell case, by the combined ranks of Conservatives and Liberals... The Labour government had lasted 259 days. On six occasions the Conservatives had saved MacDonald from defeat in the 1923 parliament, but it was the Liberals who pulled the political rung from under him." (20)

1924 General Election

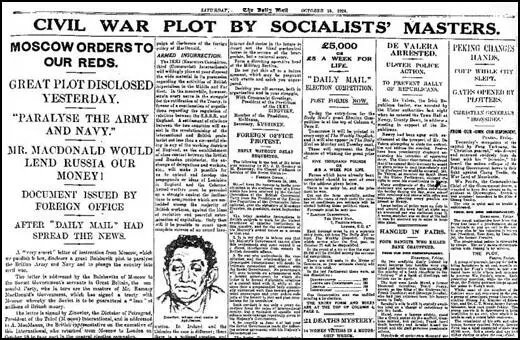

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (21)

Dora Russell, whose husband, Bertrand Russell, was standing for the Labour Party in Chelsea, commented: "The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister." (22)

Ramsay MacDonald suggested he was a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?" (23)

Bob Stewart claimed that the letter included several mistakes that made it clear it was a forgery. This included saying that Grigory Zinoviev was not the President of the Presidium of the Communist International. It also described the organisation as the "Third Communist International" whereas it was always called "Third International". Stewart argued that these "were such infantile mistakes that even a cursory examination would have shown the document to be a blatant forgery." (24)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story of what became known as the Zinoviev Letter over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (25)

David Low was a Labour Party supporter who was appalled by the tactics used by the Tory press in the 1924 General Election: "Elections have never been completely free from chicanery, of course, but this one was exceptional. There were issues - unemployment, for instance, and trade. There were legitimate secondary issues - whether or not Russia should be afforded an export loan to stimulate trade. In the event these issues were distorted, pulped, and attached as appendix to a mysterious document subsequently held by many creditable persons to be a forgery, and the election was fought on 'red panic' (The Zinoviev Letter)". (26)

After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter. It later became clear that Major George Joseph Ball, a MI5 officer, played an important role in leaking it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring. Christopher Andrew, MI5's official historian, points out: "Ball's subsequent lack of scruples in using intelligence for party political advantage while at Central Office in the late 1920s strongly suggests... that he was willing to do so during the election campaign of October 1924." (27)

Stanley Baldwin, the head of the new Conservative Party government, set up a Cabinet committee to look into the Zinoviev Letter. On 19th November, 1924, the Foreign Secretary, Austin Chamberlain, reported that members of the committee were "unanimously of opinion that there was no doubt as to the authenticity of the Letter". This judgement was based on a report written by Desmond Morton. Morton came up with "five very good reasons" why he thought the letter was genuine. These were: its source, an agent in Moscow "of proved reliability"; "direct independent confirmation" from CPGB and ARCOS sources in London; "subsidiary confirmation" in the form of supposed "frantic activity" in Moscow; because the possibility of SIS being taken in by White Russians was "entirely excluded"; and because the subject matter of the Letter was "entirely consistent with all that the Communists have been enunciating and putting into effect". Gill Bennett, who has studied the subject in great depth claims: "All five of these reasons can be shown to be misleading, if not downright false." (28) Eight days later, Morton admitted in a letter to MI5 that "we are firmly convinced this actual thing (the Zinoviev letter) is a forgery." (29)

Georgi Dimitrov, made a speech on 16th December, 1933, where he claimed that the Conservative Party was behind the the forged Zinoviev letter. "I should like also for a moment to refer to the question of forged documents. Numbers of such forgeries have been made use of against the working class. Their name is legion. There was, for example, the notorious Zinoviev letter, a letter which never emanated from Zinoviev, and which was a deliberate forgery. The British Conservative Party made effective use of the forgery against the working class." (30)

In 1996 Ken Livingstone called for an investigation into the Zinoviev Letter. "It is now believed to have been produced by two Russian emigres who were working in Berlin. They passed the forgery to an MI5 officer, Donald Thurn. Once in the hands of MI5, senior officials realised that its details of an alleged communist plot would be a devastating blow to the Labour Government in the closing days of the election campaign. MI5 leaked the letter to a Tory Member of Parliament and former intelligence officer, Sir Reginald Hall. It also leaked it to Tory central office and the Daily Mail, which obligingly ran it on its front page. In the run-up to the 1929 election, the links between MI5 and the Tory party were renewed. The head of MI5's investigation branch, Major Joseph Ball, was employed by Conservative central office to run agents inside the Labour party. After the election, Ball was rewarded with the directorship of the Tories' research department." (31)

Robin Cook, the Foreign Secretary in the Labour government elected in 1997 commissioned Gill Bennett, chief historian at the Foreign Office, to investigate the case of the Zinoviev Letter. Bennett reported that the letter was forged by a MI6 agent's source and almost certainly leaked by MI6 or MI5 officers to the Conservative Party: "It points the finger at Desmond Morton, an MI6 officer and close friend of Churchill who appointed him personal assistant during the second world war, and at Major Joseph Ball, an MI5 officer who joined Conservative Central Office in 1926." (32)

Primary Sources

(1) The Zinoviev Letter (25th September, 1924)

A settlement of relations between the two countries will assist in the revolutionizing of the international and British proletariat not less than a successful rising in any of the working districts of England, as the establishment of close contact between the British and Russian proletariat, the exchange of delegations and workers, etc. will make it possible for us to extend and develop the propaganda of ideas of Leninism in England and the Colonies.

(2) The Daily Mail (25th October, 1924)

Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind...

Meanwhile the British people, as they do not mean to have their throats cut by Zinoviev's mercenaries, must besir themselves. They must see that these miserable Bolsheviks and their stealthy British accomplices are sent to the right-about or thrown out of the country. For the safety of the nation every sane man and woman must vote on Wednesday, and vote for a Conservative Government which will know how to deal with treason.

(3) Charles Trevelyan believed that the Zinoviev letter was responsible for Labour's defeat in the 1924 General Election. His friend, Francis Hirst, wrote about the matter to him on 3rd November 1924.

I will be utterly disgusted if the Labour Cabinet timidly resign with probing the mystery (of the Zinoviev letter) and explaining it to Parliament. It's the biggest electoral swindle. I personally believe you were right in denouncing it boldly as a forgery.

(4) Ramsay MacDonald, speech in the House of Commons (24th October, 1924)

On the 21st the draft - the trial draft - was sent to me at Aberavon... I did not receive it until the 23rd. On the morning of the 24th I looked at the draft. I altered it, and sent it back in an altered form, expecting it to come back to me again with proofs of authenticity, but that night it was published.

I make no complaints... The Foreign Office and every official in it know my views about propaganda ... On account of my known determination to stand firm by agreements and to treat them as Holy Writ when my signature has been attached to them, they assumed that they were carrying out my wishes in taking immediate steps to publish the whole affair. They honestly believed that the document was authentic, and upon that belief they acted.

If they acted too precipitately, what is the accusation against us? Why don't these newspapers say we are in too great haste? Ah, that won't catch votes against you... Therefore, they have to put up the story that we shilly-shally... Only nine days have elapsed from the first registering of the letter and the publication of the dispatch last Friday.

But that is not the whole story... It came to my knowledge on Saturday... that a certain London morning newspaper... had a copy of this Zinoviev letter and was going to spring it upon us...

How did it come to have a copy of that letter? I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot...

The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?

(5) Ramsay MacDonald, diary entry (31st October, 1924)

The story of I suspect to be a forgery is as follows: Amongst the papers I dealt with before leaving my Manchester host's house oil the morning of the 16th was the copy of a letter purporting to have been sent by Zinoviev to the British Communists. I did not treat it as a proved document but as I was on the outlook for such documents and meant to deal with them firmly, I asked that care should be taken to ascertain if it was genuine, and that in the meantime a draft of a dispatch might be made to Rakovsky. I said that the dispatch would have to carry conviction and that it should be drafted with a view to being published. I was in the storm of an election and it never crossed my mind that this letter had any special part to play in the fight. Diplomatically, it was being handled with energy and precision, circulated to the Service Departments concerned and sent to Scotland Yard. The trial draft waited for me at Aberavon as I had gone to Bassetlaw to help Malcolm, Bristol etc. I found it on my return to the hotel on the 23rd, substantially rewrote it, was not satisfied with it, but being pressed to go to meetings then waiting me, I decided to send it up for copying and to make sure it would come back, did not initial it. This reached London on the 24th.

In my absence, the anti-Russian mentality of Sir Eyre Crowe was uncontrolled. He was apparently hot. He had no intention of being disloyal, indeed quite the opposite, but his own mind destroyed his discretion and blinded him to the obvious care he should have exercised. I favoured publication; he decided that I meant at once and before Rakovsky replied. I asked for care in establishing authenticity; he was satisfied and that was enough. Still, nothing untoward would have happened had not the Daily Mail and other agencies including Conservative leaders had the letter and were preparing a political bomb from it. When Sir Eyre Crowe and Mr. Gregory were actually considering the moment when the dispatch should be published, they were informed that the Daily Mail was to publish next morning and without further consideration they decided to send off the dispatch at once and give it out for publication that night.

(6) David Low, Autobiography (1956)

Labour Ministers hardly had time to get measured for their gold-braided Court suits when they were out again. Their innocuous sojourn ended after a general election which I distinguish from other elections as The Disgraceful Election. Elections have never been completely free from chicanery, of course, but this one was exceptional. There were issues - unemployment, for instance, and trade. There were legitimate secondary issues - whether or not Russia should be afforded an export loan to stimulate trade. In the event these issues were distorted, pulped, and attached as appendix to a mysterious document subsequently held by many creditable persons to be a forgery, and the election was fought on "red" panic (The Zinoviev Letter).

(7) Bertrand Russell, was the Labour Party candidate at Chelsea in the 1924 General Election. His wife, Dora Russell, wrote in her autobiography, The Tamarisk Tree, that she believed the Zinoviev letter lost Labour the election.

The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister.

(8) Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Fate Has Been Kind (1942)

The outstanding feature of the general election of 1924 in the country as a whole was the Zinoviev letter. This purported to be a document written by a prominent member of the Communist Party in Russia, and, if authentic, certainly did not make pleasant reading for the friends of the Soviet Government in this country. A copy of it was printed in one of the Conservative newspapers at the eve of the poll. The publication was a bombshell for Labour candidates everywhere. Many were defeated, and only 151 secured re-election to the House of Commons.

(9) David Kirkwood, My Life of Revolt (1935)

The people accepted the letter as genuine, just as Ramsay MacDonald had accepted it as genuine. The reply of Ramsay MacDonald only had the effect of making it seem more serious. If it had been printed by a newspaper, the people would have said: "Oh, this is a newspaper stunt." But when they saw that Ramsay MacDonald accepted it as genuine, they said : "Then why is he talking about a loan of £40,000,000 to Russia?" To them there was something sinister about it all.

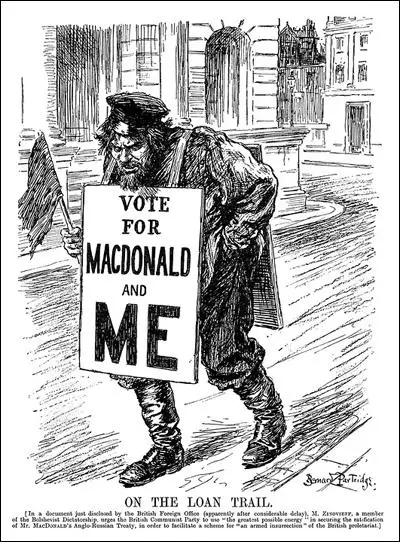

Posters appeared in which Socialist candidates were portrayed with long hair, bulging eyes, squat noses, bristling moustaches, and beards like kitchen scrubbing-brushes. It was a picture of a 'stage' Cossack'.

(10) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

The letter presumably existed a month before the press reproduced its text on the Saturday before polling day, which was a Wednesday. Ramsay MacDonald, who was Foreign Minister as well as Prime Minister, must have been aware of the letter at least ten days prior to the press revelations. He had said nothing at his election meetings nor to his colleagues in the cabinet.

With reason Jimmy Thomas commented to Philip Snowden after they had read the scare headlines: "We're sunk!" MacDonald may have thought so too, but he effectively disguised the feeling. On that Saturday afternoon he was due to address a mass meeting at Swansea. The public packed the hall to hear what he had to say about the letter, and the press were there in droves. We candidates anxiously awaited the evening papers so that we could study what we expected would be a clear lead on what to say at our meetings that Saturday evening.

There was not a single word in the MacDonald speech about it. Not until he spoke at Cardiff on Monday did he refer to it, and then he merely recited the known facts. He did not take a clear hue.

Forty-eight hours later the nation went to the polls. The Tories achieved a big victory with 419 seats. Labour members dropped from 191 to 151, and I was among the defeated.

(11) Ken Livingstone, speech in the House of Commons (10th January, 1996)

We all know about the Zinoviev letter, which led to the downfall of the first Labour Government in 1924. It is now believed to have been produced by two Russian emigres who were working in Berlin. They passed the forgery to an MI5 officer, Donald Thurn. Once in the hands of MI5, senior officials realised that its details of an alleged communist plot would be a devastating blow to the Labour Government in the closing days of the election campaign. MI5 leaked the letter to a Tory Member of Parliament and former intelligence officer, Sir Reginald Hall. It also leaked it to Tory central office and the Daily Mail, which obligingly ran it on its front page.

In the run-up to the 1929 election, the links between MI5 and the Tory party were renewed. The head of MI5's investigation branch, Major Joseph Ball, was employed by Conservative central office to run agents inside the Labour party. After the election, Ball was rewarded with the directorship of the Tories' research department.

(12) Richard Norton-Taylor, The Guardian (4th February, 1999)

The Zinoviev letter - one of the greatest British political scandals of this century - was forged by a MI6 agent's source and almost certainly leaked by MI6 or MI5 officers to the Conservative Party, according to an official report published today.

New light on the scandal which triggered the fall of the first Labour government in 1924 is shed in a study by Gill Bennett, chief historian at the Foreign Office, commissioned by Robin Cook.

It points the finger at Desmond Morton, an MI6 officer and close friend of Churchill who appointed him personal assistant during the second world war, and at Major Joseph Ball, an MI5 officer who joined Conservative Central Office in 1926.

The exact route of the forged letter to the Daily Mail will never be known, Ms Bennett said yesterday. There were other possible conduits, including Stewart Menzies, a future head of MI6 who, according to MI6 files, admitted sending a copy to the Daily Mail.

The letter, purported to be from Grigori Zinoviev, president of the Comintern, the internal communist organisation, called on British communists to mobilise "sympathetic forces" in the Labour Party to support an Anglo-Soviet treaty (including a loan to the Bolshevik government) and to encourage "agitation-propaganda" in the armed forces.

On October 25, 1924, four days before the election, the Mail splashed headlines across its front page claiming: Civil War Plot by Socialists' Masters: Moscow Orders To Our Reds; Great Plot Disclosed. Labour lost by a landslide.

Ms Bennett said the letter "probably was leaked from SIS [the Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known as MI6] by somebody to the Conservative Party Central Office". She named Major Ball and Mr Morton, who was responsible for assessing agents' reports.

"I have my doubts as to whether he thought it was genuine but [Morton] treated it as if it was," she said. She described MI6 as being at the centre of the scandal, although it was impossible to say whether the head of MI6, Admiral Hugh Sinclair, was involved.

She said there was no evidence of a conspiracy in what she called "the institutional sense". The security and intelligence community at the time consisted of a "very, very incestuous circle, an elite network" who went to school together. Their allegiances, she says in her report, "lay firmly in the Conservative camp".

Ms Bennett had full access to secret files held by MI6 (some have been destroyed) and MI5. She also saw Soviet archives in Moscow before writing her 128-page study. The files show the forged Zinoviev letter was widely circulated, including to senior army officers, to inflict maximum damage on the Labour government.

She found no evidence to identify the name of the forger. She said the letter - sent to MI6 from one of its agents in the Latvian capital, Riga - was written as a result of a campaign orchestrated by White Russians who had good contacts in London who were strongly opposed to the Anglo-Soviet treaty.

The report says there is no hard evidence that MI6 agents in Riga were directly responsible - though it is known they had close contacts with White Russians - or that the letter was commissioned in response to British intelligence services' "uneasiness about its prospects under a re-elected Labour government".

However, if Ms Bennett is right in her suggestion that MI6 chiefs did not set up the forgery, her report makes clear that MI6 deceived the Foreign Office by asserting it did know who the source was - a deception it used to insist, wrongly, that the Zinoviev letter was genuine.

(13) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009)

Allegedly dispatched by Zinoviev and two other members of the Comintern Executive Committee on 15 September 1924, the letter instructed the CPGB leadership to put pressure on their sympathizers in the Labour Party, to "strain every nerve" for the ratification of the recent treaty concluded by MacDonald's government with the Soviet Union, to intensify "agitation-propaganda work in the armed forces", and generally to prepare for the coming of the British revolution. On 9 October SIS forwarded copies to the Foreign Office, MIS, Scotland Yard and the service ministries, together with an ill-founded assurance that "the authenticity is undoubted". The unauthorized publication of the letter in the Conservative Daily Mail on 25 October in the final week of the election campaign turned it into what MacDonald called a "political bomb", which those responsible intended to sabotage Labour's prospects of victory by suggesting that it was susceptible to Communist pressure.

The call in the Zinoviev letter for the CPGB to engage in 'agitation-propaganda work in the armed forces" placed it squarely within MI5's sphere of action. Like others familiar with Comintern communications and Soviet intercepts, Kell was not surprised by the letter's contents, believing it "contained nothing new or different from the (known) intentions and propaganda of the USSR." He had seen similar statements in authentic intercepted correspondence from Comintern to the CPGB and the National Minority Movement (the Communist-led trade union organization), and is likely - at least initially - to have had no difficulty in accepting SIS's assurance that the Zinoviev letter was genuine. The assurance, however, should never have been given. Outrageously, Desmond Morton of SIS told Sir Eyre Crowe, PUS at the Foreign Office, that one of Sir George Mahgill's agents, "Jim Finney", who had penetrated the CPGB, had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter. On the basis of that information, Crowe had told MacDonald that he had heard on "absolutely reliable authority" that the letter had been discussed by the Party leadership. In reality, Finney's report of a discussion by the CPGB Executive made no mention of any letter from Moscow. MI5's own sources failed to corroborate SIS's claim that the letter had been received and discussed by the CPGB leadership - unsurprisingly, since the letter had never in fact been sent.

MI5 had little to do with the official handling of the Zinoviev letter, apart from distributing copies to army commands on 22 October 1924, no doubt to alert them to its call for subversion in the armed forces. The possible unofficial role of a few MI5 officers past and present in publicizing the Zinoviev letter with the aim of ensuring Labour's defeat at the polls remains a murky area on which surviving Security Service archives shed little light. Other sources, however, provide some clues. A wartime MI5 officer, Donald Thurn ("recreations: golf, football, cricket, hockey, fencing"), who had served in MI5 from December 1917 to June 1919, made strenuous attempts to ensure the publication of the Zinoviev letter and may well have alerted the Mail and Conservative Central Office to its existence. Thurn later claimed implausibly to have obtained a copy of the letter from a business friend with Communist contacts who subsequently had to flee to "a place of safety" because his life was in danger. This unlikely tale was probably invented to avoid compromising his intelligence contacts. After Thurn left the Service for the City in 1919, he continued to lunch regularly in the grill-room of the Hyde Park Hotel with Major William Alexander of B Branch (an Oxford graduate who had qualified as a barrister before the First World War). Thurn was also well acquainted with the Chief of SIS, Admiral Quex Sinclair. Though he was not shown the actual text of the Zinoviev letter before publication, one or more of his intelligence contacts briefed him on its contents. Alexander appears to have informed Im Thurn on 21 October that the text was about to be circulated to army commands. Suspicion also attaches to the role of the head of B Branch, Joseph Ball. Conservative Central Office, with which Ball had close contacts, probably had a copy of the Zinoviev letter by 22 October, three days before publication. Ball's subsequent lack of scruples in using intelligence for party-political advantage while at Central Office in the later 1920's strongly suggests, but does not prove, that he was willing to do so during the election campaign of October 1924. But Ball was not alone. Others involved in the publication of the Zinoviev letter probably included the former DNI, Admiral Blinker Hall, and Lieutenant Colonel Freddie Browning, Cumming's former deputy and a friend of both Hall and the editor of the Mail. Hall and Browning, like Im Thurn, Alexander, Sinclair and Ball, were part of a deeply conservative, strongly patriotic establishment network who were accustomed to sharing state secrets between themselves: "Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion."

Those who conspired together in October 1924 convinced themselves that they were acting in the national interest - to remove from power a government whose susceptibility to Soviet and pro-Soviet pressure made it a threat to national security. Though the Zinoviev letter was not the main cause of the Tory election landslide on 29 October, many politicians on both left and right believed that it was. Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told his rival Lord Rothermere, proprietor of the Daily Mail, that the Mail's "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere immodestly agreed that he had won a hundred seats. Labour leaders were inclined to agree. They felt they had been tricked out of office. And their suspicions seemed to be confirmed when they discovered the part played by Conservative Central Office in the publication of the letter.

(14) Gill Bennett, Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009)

Morton's own explanation, that Finney "elaborated" on his written report, is therefore invalidated. It is possible that Morton conflated, accidentally or deliberately, Finney's report with the report from Latvia received the day before. If accidentally, it implies a casualness that does not sit well with Morton's known modus operandi; if deliberately, the reason may not necessarily be sinister. Morton received a great many such reports across his desk, the majority of which were genuine. He may have believed, sincerely, in the authenticity of the letter at that point. On the other hand, it might be that since he, like many of his colleagues and contacts (including his own Chief), detested the Bolsheviks and disliked the Labour Government, he welcomed the chance to throw a spanner in the works of Anglo-Soviet rapprochement. He may have been influenced, or even instructed, to do so.

The propagation of conspiracy theories is always unprofitable, as it is impossible to prove a negative. There is no hard evidence to explain Morton's actions or motives, and he never revealed them (adding extra fuel to the conspiratorial fire in an interview in 1969, when he claimed that Menzies had posted a copy of the letter to the Daily Mail because he disliked Labour). The surviving documentation is, as so often with Morton, contradictory. By the beginning of November 1924 SIS had begun to receive reports from SIS stations that the letter was a forgery, probably originating in the Baltic States; Morton wrote to M15 on 27 November that "we are firmly convinced this actual thing is a forgery". Meanwhile, however, two Cabinet Committees had been convened to consider the question of the Letter's authenticity: the first, chaired by MacDonald, reported to the Cabinet on 4 November that they "found it impossible on the evidence before them to come to a conclusion on the subject"; it was the last act of his ill-fated Government. The second, however, chaired by the new Foreign Secretary Sir Austen Chamberlain, reported on 19 November that its members were "unanimously of opinion that there was no doubt as to the authenticity of the Letter".

Meanwhile, on 17 November Sinclair submitted to Crowe, for consideration by the Chamberlain Committee, a document, apparently drafted by Morton, containing "five very good reasons" why SIS considered the Letter genuine. These were: its source, an agent in Moscow "of proved reliability"; "direct independent confirmation" from CPGB and ARCOS sources in London; "subsidiary confirmation" in the form of supposed "frantic activity" in Moscow; because the possibility of SIS being taken in by White Russians was "entirely excluded"; and because the subject matter of the Letter was "entirely consistent with all that the Communists have been enunciating and putting into effect". All five of these reasons can be shown to be misleading, if not downright false. SIS did not know, for example, the identity of the agent in Moscow said to have provided the letter, and were certainly not, as the document claimed, "aware of the identity of every person who handled the document on its journey from Zinoviev's files to our hands".

The "independent and spontaneous confirmation" that the CPGB had received the letter was, as has been seen, of decidedly suspect provenance, while reports of arrests in Moscow were no more than circumstantial. The claim that SIS was incapable of being taken in by White Russian forgers was more aspirational than accurate, while the final reason, that the letter was consonant with Communist policy and "If it was a forgery, by this time we should have proof of it", may have been unanswerable, but was disingenuous in the light of reports received in the previous month.

This documentary sophistry, not to say prevarication, cannot fail to arouse the suspicion that Morton, and indeed SIS, had something to hide, not just about how the letter came to be given to the Press, but also about its origin. Orlov's Berlin organisation, with whom Morton remained in touch and about which he received regular information, was identified quickly as a likely potential source of the forgery, and although the account published by the Sunday Times "Insight" team in 1967, alleging that one of Orlov's colleagues, Alexis Bellegarde, forged the letter begs more questions than it answers, there is no doubt that Orlov had the opportunity and contacts required. It would, as one SIS account noted, have been easy enough for him to put in touch with a foreign intelligence service, e.g. in Riga, some well-trained agent of his own who would thereafter produce material purporting to be obtained from Moscow or elsewhere, but which was, in fact, prepared by himself. It was part of Morton's job to pay close attention to "expert" forgeries emanating from sources such as Orlov's service...

The way the letter was handled once it reached SIS, and its communication to the press, also arouses suspicion, heightened by what is now known about the activities of some of Morton's contacts: the Makgill organisation; White Russian groups at home and abroad; the head of the FO's Northern Department, J.D. Gregory, an old "Russia hand" later shown to have been engaging in decidedly unethical (if inept) currency trading at this time in company with his mistress Mrs Aminta Bradley Dyne - whose husband was another old "Russia hand". Although a Treasury Committee of Enquiry held in 1928 was unable to establish any direct connection between Gregory's activities and the Zinoviev Letter, suspicions remained." Similarly, doubts have been raised as to whether Morton's contacts with Ball at MIS were politically as well as professionally motivated: and the involvement of former M15 officer Donald im Thurn, who tried to sell a copy of the letter (which he did not possess), adds another mysterious dimension to the story; the names of the former DNI, Admiral Blinker Hall, and former Deputy Chief of SIS, Frederick Browning, have also been implicated.

(15) Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service (2010)

It (the Zinoviev Letter) took about a week to reach London and, having been evaluated by Desmond Morton, was circulated by SIS on 9 October to the Foreign Office and other departments. A covering note said that the document contained "strong incitement to armed revolution" and "evidence of intention to contaminate the Armed Forces", and was "a flagrant violation" of "the Anglo-Russian Treaty signed on the 8th August". Though, apparently, no systematic checks had been made, SIS also categorically vouched that "the authenticity of the document is undoubted".

The Foreign Office, nevertheless, carefully sought further corroboration from SIS. This was provided by Desmond Morton on 11 October based (he maintained) on information received from "Jim Finney" (code-named "Furniture Dealer"), one of the agents jointly run with Makgill's organisation, who had been infiltrated into the Communist Party of Great Britain. According to Morton, Finney reported that the Party Central Committee had recently received a letter of instruction from Moscow concerning "action which the C.P.G.B. was to take with regard to making the proletariat force Parliament to ratify the Anglo-Soviet Treaty" and that "particular efforts were to be made to permeate the Armed Forces of the Crown with Communist agents". This, concluded Morton, "seems undoubtedly confirmation of the receipt by the C.P.G.B. of Zinoviev's letter". But the original report contained no reference to any particular communication from Moscow, and Morton said he had ascertained details of a specific letter only during a subsequent meeting with the agent. Reflecting how curious it was that the agent had not mentioned so apparently significant a directive from Moscow in the original report, Milicent Bagot, a retired

M15 officer who spent three years in the late 1960s exhaustively investigating the affair, suggested that the agent had been asked "loaded" questions by Morton, who is known to have been working on the Riga report and had no doubt put the two together in his mind.

On 13 October SIS assured Sir Eyre Crowe that Morton's information provided "strong confirmation of the genuineness of our document (the Zinoviev Letter)". This was interpreted by Crowe as "absolutely reliable authority that the Russian letter was received and discussed at a recent meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain", and on this basis he recommended to MacDonald that a formal note of protest be submitted and full information be given to the press.

Morton's "strong confirmation", therefore, already perhaps more than the evidence supported, became "absolutely reliable authority", and the basis for explicit government action. It was only after the Soviet charge, Christian Rakovsky, had dismissed the letter as "a gross forgery" (which it almost certainly was) that on 27 October Crowe asked Malcolm Woollcombe for further information. Had, for example, the text been received in English or Russian and could an SIS officer explain things personally to the Prime Minister, who in the meantime had himself begun to wonder if the letter were bogus? Riga told Head Office that their original version had been in Russian, which had been translated by a secretary in the station before transmission to London, thus revealing that the English text was not quite as "authentic" as had at first been claimed.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject