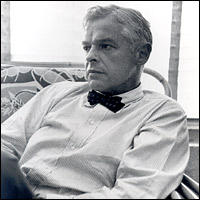

Paul Nitze

Paul Henry Nitze was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on 16th January, 1907. After graduating from Harvard University in 1927 he worked as an investment banker in Wall Street. Over the next few years Nitze became extremely wealthy from his business activities in New York. During this period he worked for C. Douglas Dillon and Jim Forrestal at Dillon, Read & Company.

In 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Jim Forrestal as under secretary of the navy with special responsibility for procurement and production. Forrestal invited Nitze to join him in Washington. In 1944 Nitze became vice chairman of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey. In this post he played an important role in the decision to drop nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war Nitze married Phyllis Pratt, a Standard Oil heiress.While in Washington he associated with a group of journalists, politicians and government officials that became known as the Georgetown Set. This included Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, Joseph Alsop, Stewart Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Thomas Braden, Philip Graham, David Bruce, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen, Cord Meyer, James Angleton, William Averill Harriman, John McCloy, Felix Frankfurter, John Sherman Cooper, James Reston, and Allen W. Dulles.

In 1950 Nitze became head of Policy Planning in the State Department. In this post he was the principal author of a highly influential secret National Security Council document, United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC-68), which provided the strategic outline for increased U.S. expenditures to counter the perceived threat of the Soviet Union.

After the resignation of Fred Korth as a result of the TFX scandal, President John F. Kennedy appointed Nitze as Secretary of the Navy. He retained this position under President Lyndon Johnson. In 1967 Nitze became Deputy Secretary of Defense.

In 1969 President Richard Nixon appointed Nitze as a member of the US delegation to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). Nitze also served as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Affairs (1973–76).

In August 1975, the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) wrote a letter to President Gerald Ford proposing that an outside group of experts be given access to the same intelligence as the CIA analysts and be allowed to prepare a competing National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) and then make an evaluation. The outside group would be called the B Team. The CIA and the intelligence community estimates would be the A Team.

William Colby, the director of the CIA, rejected the idea. On 30 January 1976, Gerald Ford sacked Colby and replaced him with George H. W. Bush. Soon afterwards Bush agreed to the setting up a B Team. As a result of this move, outsiders would now have access to all of America's classified knowledge about the Soviet Military. Hank Knoche, Bush's deputy, was ordered to organize this new system. Interestingly, Paisley was brought out of retirement to become the CIA 'coordinator' for the B Team. It was Paisley who would control the documents that they saw and the information they received.

Members of the B Team included Paul Nitze, Richard E. Pipes, Clare Boothe Luce, John Connally, General Daniel O. Graham, Edward Teller, Paul Wolfowitz (Arms Control and Disarmament Agency), General John W. Vogt, Brigadier General Jasper A. Welch, William van Cleeve (University of Southern California), Foy D. Kohler (U.S. Ambassador to Moscow), Seymour Weiss (State Department) and Thomas W. Wolfe (Rand Corporation).

Nitze constantly feared the possibility of Soviet rearmament and in 1979 opposed the ratification of SALT II. As a result President Jimmy Carter was forced to withdraw the Salt Treaty.

In 1981 President Ronald Reagan appointed him as chief negotiator of the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty. In 1984 he was named special adviser to the President and Secretary of State on Arms Control.

Paul Nitze died on 19th October, 2004.

Primary Sources

(1) Evan Thomas, The Very Best Men: The Early Days of the CIA (1995)

When Wisner moved to Washington, he bought a farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and rented a house in Georgetown. He immediately fell in with a crowd that was unusually lively and self-confident. At the center were two rising Soviet experts from the State Department, Charles "Chip" Bohlen and George Kennan. Bohlen was especially charming and gregarious. He loved to argue with his college clubmates Joseph Alsop, a well-connected newspaper columnist, and Paul Nitze, another young comer at the State Department. Kennan, while admired for his intellect, was less socially at ease; he was prone to periods of brooding.

The young couples, lawyers down from New York, diplomats returned from abroad, bought or rented small eighteenth- and nineteenth-century row houses in Georgetown. The New Deal and wartime had transformed the neighborhood from a backwater, inhabited largely by lower-middle-class blacks. The new crowd felt a sense of arrival and belonging. They were not stuffy, like the old-time "cave dwellers" of Washington society, yet they were confident of their place in a new order that placed the United States on top.

(2) Fred Kaplan, Paul Nitze: The man who brought us the Cold War (1996)

When Paul Henry Nitze died at the age of 97 on Oct. 19, an era died with him. If there was one man responsible for America's emergence as a global military power in the mid-20th century, Nitze could lay claim to that credit. If one man was most responsible for the nuclear nightmares that many Americans suffered along the way, Nitze could wear that tag as well.

In the annals of Cold War history, three sets of documents stand out as potent hair-raiser, the kinds of documents that not only gave their readers cold sweats, but also changed the course of American security policy - and Nitze wrote all of them.

The first and most pivotal was a top secret paper, written in April 1950, called "United States Objectives and Programs for National Security," more famously known as NSC-68. In the months leading up to this paper, the Truman administration was split on its policy toward the Soviet Union. Secretary of State Dean Acheson saw the Soviets as a serious threat that needed to be countered through an enormous military buildup. Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson sided with fiscal conservatives - and Truman himself - who believed that boosting the annual arms budget beyond $15 billion would wreck the economy. Acheson's powerful policy planning chief, George Kennan, though worried about the Soviets, favored a "containment" policy that stressed bolstering the West more through political and economic means.

At the beginning of 1950, Acheson fired Kennan and put Nitze in his place. Nitze, a former Wall Street banker, had been one of Kennan's deputies, but openly sympathized with Acheson. Nitze's first task: Scare the daylights out of Truman, so he'd raise the military budget. NSC-68 was the vehicle for doing so.

The document (which was declassified in the mid-1970s) warned of the "Kremlin's design for world domination," an urge it posited as intrinsic to Soviet Russia. "The Kremlin is inescapably militant," the paper argued. The Soviet system required "the ultimate elimination of any effective opposition," and so it would inexorably seek to destroy its main opponent, the United States. Moreover, the paper continued, once the Kremlin "calculates that it has a sufficient atomic capability to make a surprise attack on us," it might very well launch such an attack "swiftly and with stealth." The Soviets would have this capability as early as 1954 - "the year of maximum danger" - unless the United States "substantially increased" its army, navy, air force, nuclear arsenal, and civil defenses immediately.

Years later, in his memoir, Present at the Creation, Acheson admitted that the language was "clearer than truth," as he put it, but justified the hype. "The purpose of NSC-68," he wrote, "was to so bludgeon the mass mind of 'top government' that not only could the President make a decision but that the decision could be carried out."

(3) William Burr and Robert Wampler, The Master of the Game (27th October, 2004)

The recent passing of Paul Nitze at the age of 97 has brought forth the expected array of obituaries, retrospectives and assessments of his lengthy and often controversial career, in the process turning people's minds back to an era when superpower rivalry and the threat of nuclear annihilation hung over the world as the United States and Russia engaged in what John F. Kennedy termed the long, twilight struggle. As the many obituaries that have appeared since his death detail, Nitze's life in public service, following a successful early career as a Wall Street financier, placed him at the center of practically every significant decision or debate about U.S. Cold War strategy and nuclear weapons policies, though not always at the highest levels. As his memoir, titled From Hiroshima to Glasnost, underscores, this career stretched from his work with the World War II Strategic Bombing Survey, which placed him in Hiroshima and Nagasaki soon after the atomic bombs were dropped, to his negotiations with the Soviets on intermediate nuclear forces under Reagan. His commitment to rigorous analysis and advocacy of what he saw as the logical consequences of this analysis in strategic planning and arms control negotiations often put him at odds with colleagues as well as his adversaries and critics, who saw his assessments as biased towards worst-case scenarios. Both Nitze's memoir and his biographers have detailed the history of his often contentious battles, inside and outside of government, whenever he believed that U.S. was pursuing ill-advised and even dangerous policies with respect to fielding the necessary levels and proper mix of military forces both conventional and nuclear, and pursuing arms control agreements with the USSR.

(4) Hella Pick, Paul Nitze, The Guardian (22nd October, 2004)

There is no single label to fit Nitze. This slim, silver-haired, courteous man was the ultimate Washington insider, one of the small handful of Americans who chose public service rather than politics and achieved positions of great influence. He shaped US foreign and security policies from 1940 onwards, working for both Democratic and Republican presidents through to the first Bush administration, and remained in the limelight almost to the end.

Nitze was a Democrat, but for much of the cold war his hawkish views were more in line with mainstream Republican thinking. He plotted US nuclear policy throughout the era of "mutually assured destruction". But Nitze was also ahead of many of his contemporaries from the early 1980s onwards, when he became convinced that the two superpowers should embark on radical arms cuts. He mastered every nook and cranny of nuclear strategic thinking, but was sharply critical of President Reagan's Star Wars initiative: he did not share the widely held view that the costly race to develop nuclear defence system was justified