Anne Truitt

Anne Dean was born in Baltimore on 16th March, 1921, but brought up in Easton, Maryland. According to Nina Burleigh: "Anne Truitt had been raised on Maryland's Eastern Shore in a genteel southern family". (1) Her mother came from Boston and worked as a nurse during the First World War. (2)

Matt Schudel has pointed out that in her late teens, she was sent to North Carolina to "recover from a burst appendix and spent a summer playing volleyball" with Zelda Fitzgerald, who was a patient at a nearby psychiatric hospital. (3)

Anne graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a degree in psychology in 1943. She worked in psychiatric research in Boston and as a volunteer nurse's aide for the Red Cross, during the Second World War. "If you’re a nurse, it’s an extraordinary situation really. It’s intimate. If you’re a nurse, you walk into a room and there’s a patient. The patient is a full-grown, usually, human being, and they’re frightened. They’re scared and they’re anxious and they hurt, and you have to make the bed for them and give them a bath. It’s very intimate. The whole thing is -- you put your hands on their bodies." (4)

Marriage to James Truitt

In 1945 Anne met James Truitt: "Toward the end of the war, one of the other people -- I went in to have tea with her one afternoon. We used to have tea on Sunday afternoon and drink tea with a little rum in it and listen to the chamber music. I went in and there was this extremely attractive young naval officer just back from the Pacific. He had blue eyes and yellow hair and he looked like me. He looked like my brother. And he was born in Baltimore -- or born in Chicago but grew up in Baltimore, and he went to Ocean City when he was a child, just as I did... And he was a restless -- a restless, vibrant, curious, intellectual, entertaining man." (5)

In September, 1947, Anne married Truitt. At the time he was working in the State Department but in 1948 he went to work for Life Magazine. He spent three years with the magazine in San Francisco before moving to Washington. During this period she gave birth to three children Alexandra, Mary and Sam. (6) At this time James Truitt was described as "physically compact, he wore his sandy hair in an extremely short brush cut... charming and genteel, cigarette always in hand, he gave the impression of a man of street savviness and constant movement." (7)

Anne was a talented artist who came under the influence of Kenneth Noland. Her closest friend was Mary Pinchot Meyer, the wife of Cord Meyer, a senior figure in the CIA. Mary was also an artist. Cicely Angleton, the wife of James Jesus Angleton, was also interested in art. According to Nina Burleigh, the author of A Very Private Woman (1998): "The Angletons, Truitts, and Meyers grew very close, and they were especially bound together by their mutual interest in art and culture." (8)

During this period the Truitts became friends with a group of people living in Georgetown. This included Mary Pinchot Meyer, Cord Meyer, Frank Wisner, George Kennan, Dean Acheson, Thomas Braden, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, James Jesus Angleton, Cicely Angleton, Wistar Janney, Joseph Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Philip Graham, Katharine Graham, David Bruce, Ben Bradlee, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen and Paul Nitze. They were mainly journalists, CIA officers and government officials. Nina Burleigh has pointed out: "The younger families - the Meyers, Janneys, Truitts, Pittmans, Lanahans, and Angletons - spent a great deal of leisure time together. There were evening get-togethers, and sometimes the families took weekend camping trips to nearby beaches or mountains when husbands could get away... On Saturday mornings in the fall, the adults got together and played touch football in a park north of Georgetown while their children biked around the sidelines, then all retired to someone's house for lunch and drinks... The Janneys had a pool, and on hot summer nights the parties were aloud, drunken affairs, filled with laughter, dancing, and the sound of breaking glass and people being pushed into the pool." (9)

Anne Truitt - Artist

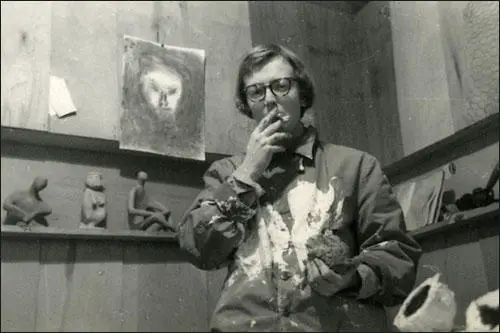

Anne was a talented artist and according to Matt Schudel: "As early as the 1960s, she was considered a leader in the minimalist school of art, a label she reluctantly accepted even though her work defied simple classification... In 1961, she discovered her mature style, creating standing rectangular sculptures painted in subtle, precisely shaded colors. Set on slightly recessed bases, they appear to hover just above the floor. She was immediately identified with the emerging minimalist movement." (10)

In May 1960 James Truitt become the personal assistant to Philip Graham at the Washington Post, where he rose to become vice president. (11) A close friend, David Middleton recalled: "Truitt was incredibly smart, incredibly well read." He also knew a great deal about art: "Truitt had sophisticated and broad tastes in art. He collected Korean art and Japanese primitive art. He was eccentric and experimental. He kept an alligator in the bathtub of his Georgetown house for a time." Truitt became close to Mary Pinchot Meyer: "Eventually he came to regard Mary Meyer as his spiritual sister, probably because her experimental nature was so like his own." This caused problems for Anne Truitt: "Her relationship with Mary was complicated. She adored and admired her, but she was eventually hurt by her husband's attention to her friend." (12)

Anne Truitt disliked the idea of being under the financial control of her husband and this caused problems in their marriage: "I had actually eaten food earned by someone else. I tasted something slimy and rotten in my mouth and felt a kind of servitude utterly familiar. With the force of a blow to my solar plexus, I felt clearly the position I had placed myself in. I had been beholden to James for the food in my mouth... I owed him something because he kept me and the children - and that's the truth, I owed him." (13)

Mary Pinchot Meyer & John F. Kennedy

In January, 1962, Mary Pinchot Meyer began a sexual relationship with President John F. Kennedy. (32) Charles Bartlett, a journalist who ran the Washington bureau of the Chattanooga Times, and a close friend of Kennedy's became concerned about the affair: "I really liked Jack Kennedy. We had great fun together and a lot of things in common. We had a very personal, close relationship... Jack was in love with Mary Meyer. He was certainly smitten by her, he was heavily smitten. He was very frank with me about it, that he thought she was absolutely great.... It was a dangerous relationship." (14)

White House gate logs show Mary Meyer signed in to see the president at or around 7.30 p.m. on fifteen occasions between October 1961 and August 1963, always when Jacqueline Kennedy is known to have been away from Washington, with one exception when her whereabouts are not verifiable by White House records or news reports. "The gate logs do not tell the entire story of who was in the White House, because there were other entrances and many occasions when people have said they were inside the White House without being signed... The fact that Mary Meyer's name is so often entered means she was not hidden and was probably there more often than the logs indicate." (15) Kenny O'Donnell told Leo Damore, that in October 1963 Kennedy told him that he "was deeply in love with Mary, that after he left the White House he envisioned a future with her and would divorce Jackie." (16)

Mary Meyer told Anne and James Truitt about her relationship with Kennedy. "Mary apparently told the Truitts about her meetings with the president while they were happening, and Truitt kept notes with dates, times, and details. It is unclear whether Mary knew of or approved of Truitt's note-taking, although she did tell a female friend during this period that she regarded her trysts with Kennedy as interesting history." (17)

Mary Meyer told Anne and James Truitt about her relationship with Kennedy. "Mary apparently told the Truitts about her meetings with the president while they were happening, and Truitt kept notes with dates, times, and details. It is unclear whether Mary knew of or approved of Truitt's note-taking, although she did tell a female friend during this period that she regarded her trysts with Kennedy as interesting history." (17) Mary also told them that she was keeping a diary about the relationship and asked the Truitts to take possession of a private diary "if anything ever happened to me".

Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer

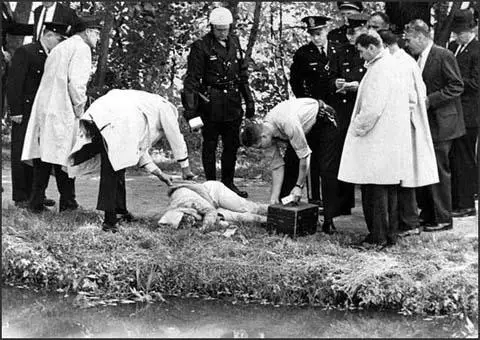

In 1963 James Truitt was sent to Tokyo in order to become the Japan bureau chief for Newsweek. Anne was with James when Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot dead as she walked along the Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown on 12th October, 1964. Mary appeared to be killed by a professional hitman. The first bullet was fired at the back of the head. She did not die straight away. A second shot was fired into the heart. The evidence suggests that in both cases, the gun was virtually touching Mary’s body when it was fired. As the FBI expert testified, the “dark haloes on the skin around both entry wounds suggested they had been fired at close-range, possibly point-blank”. (18)

Ben Bradlee points out that the first he heard of the death of Mary Pinchot Meyer was when he received a phone-call from Wistar Janney, his friend who worked for the CIA: "My friend Wistar Janney called to ask if I had been listening to the radio. It was just after lunch, and of course I had not. Next he asked if I knew where Mary was, and of course I didn't. Someone had been murdered on the towpath, he said, and from the radio description it sounded like Mary. I raced home. Tony was coping by worrying about children, hers and Mary's, and about her mother, who was seventy-one years old, living alone in New York. We asked Anne Chamberlin, Mary's college roommate, to go to New York and bring Ruth to us. When Ann was well on her way, I was delegated to break the news to Ruth on the telephone. I can't remember that conversation. I was so scared for her, for my family, and for what was happening to our world. Next, the police told us, someone would have to identify Mary's body in the morgue, and since Mary and her husband, Cord Meyer, were separated, I drew that straw too." (19)

Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has questioned this account of events provided by Bradlee. "How could Bradlee's CIA friend have known 'just after lunch' that the murdered woman was Mary Meyer when the victim's identity was still unknown to police? Did the caller wonder if the woman was Mary, or did he know it, and if so, how? This distinction is critical, and it goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding Mary Meyer's murder." Janney even questions if it really was his father who phoned Bradlee. He points out that Wistar Janney had died a year before Bradlee published his account of events. (20)

That night Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee received a telephone call from Anne Truitt. She told her that it "was a matter of some urgency that she found Mary's diary before the police got to it and her private life became a matter of public record". (21) Mary had apparently told Anne that "if anything ever happened to me" you must take possession of my "private diary". Ben Bradlee explains in The Good Life (1995): "We didn't start looking until the next morning, when Tony and I walked around the corner a few blocks to Mary's house. It was locked, as we had expected, but when we got inside, we found Jim Angleton, and to our complete surprise he told us he, too, was looking for Mary's diary." (22)

James Jesus Angleton later claimed that he had also received a telephone call from Anne Truitt. His wife, Cicely Angleton, confirmed this in an interview given to Nina Burleigh. (23) However, an article by Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, in the New Times on 9th July, 1976, gives a different version of events with the Angleton's arriving at Mary's house that evening to attend a poetry reading and that at this stage they did not know she was dead. (24)

Joseph Trento, the author of Secret History of the CIA (2001), has pointed out: "Cicely Angleton called her husband at work to ask him to check on a radio report she had heard that a woman had been shot to death along the old Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Walking along that towpath, which ran near her home, was Mary Meyer's favorite exercise, and Cicely, knowing her routine, was worried. James Angleton dismissed his wife's worry, pointing out that there was no reason to suppose the dead woman was Mary - many people walked along the towpath. When the Angletons arrived at Mary Meyer's house that evening, she was not home. A phone call to her answering service proved that Cicely's anxiety had not been misplaced: Their friend had been murdered that afternoon." (25)

Divorce

Ben Bradlee sacked James Truitt in 1969. As part of his settlement he took $35,000 on the written condition that he did not write anything for publication about his experiences at the Washington Post that was "in any way derogatory" of the company. Truitt began to drink heavily and this had an impact on their marriage. The couple were divorced in 1971. Anne blamed the Second World War for the changes that had taken place in her husband. "Confronted by the probability of their own deaths, it seems to me that many of the most percipient men of my generation killed off those parts of themselves that were most vulnerable to pain, and thus lost forever a delicacy of feeling on which intimacy depends. To a less tragic extent we women also had to harden ourselves with them." (26)

Over the next few years Anne Truitt established herself as an important artist. Matt Schudel has pointed out: "For more than 40 years, Mrs. Truitt was a major figure in American art, best known for her richly painted sculptures of vertical blocks of wood.... A supremely disciplined artist, she rose early each morning to work in the studio behind her home in Cleveland Park. She occasionally did drawings or paintings, but she most often made abstract sculptures from standing blocks of wood five to seven feet high. After sanding the wood to a smooth finish and priming it with several coats of gesso, a plaster of Paris mixture, she applied coat after coat of acrylic paint until the blocks acquired a mesmerizing visual intensity." (27)

In 1995 Ben Bradlee published The Good Life (1995), Anne Truitt and Cicely Angleton wrote a letter to the New York Times Book Review to "correct what in our opinion is an error" in Bradlee's autobiography: "This error occurs in Mr. Bradlee's account of the discovery and disposition of Mary Pinchot Meyer's personal diary. The fact is that Mary Meyer asked Anne Truitt to make sure that in the event of anything happening to Mary while Anne was in Japan, James Angleton take this diary into his safekeeping. When she learned that Mary had been killed, Anne Truitt telephoned person-to-person from Tokyo for James Angleton. She found him at Mr. Bradlee's house, where Angleton and his wife, Cicely had been asked to come following the murder. In the phone call, relaying Mary Meyer's specific instructions, Anne Truitt told Angleton for the first time, that there was a diary; and in accordance with Mary Meyer's explicit request, Anne Truitt asked Angleton to search for and take charge of the diary." (28)

Anne Truitt developed peritonitis and other complications from emergency surgery and died at Sibley Memorial Hospital at age 83 on 23rd December, 2004.

Primary Sources

(1) Matt Schudel, The Washington Post (25th December, 2004)

One of Washington's foremost artists, Anne Truitt, acclaimed for her graceful sculptures and for her sensitive, deeply learned writings about her life and work, died Dec. 23 at Sibley Memorial Hospital at age 83. She developed peritonitis and other complications from emergency surgery more than a week before. She had been a Washington resident since 1947.

For more than 40 years, Mrs. Truitt was a major figure in American art, best known for her richly painted sculptures of vertical blocks of wood. As early as the 1960s, she was considered a leader in the minimalist school of art, a label she reluctantly accepted even though her work defied simple classification.

A supremely disciplined artist, she rose early each morning to work in the studio behind her home in Cleveland Park. She occasionally did drawings or paintings, but she most often made abstract sculptures from standing blocks of wood five to seven feet high. After sanding the wood to a smooth finish and priming it with several coats of gesso, a plaster of Paris mixture, she applied coat after coat of acrylic paint until the blocks acquired a mesmerizing visual intensity.

"They became almost translucent," said Renato Danese, who represented Mrs. Truitt at his New York art gallery since 1997. "Painting and sculpture were conjoined. They were one and the same."

She was admired by other artists for the integrity and independence of her vision, which seemed to burn more intensely as she grew older. After she turned 60, Mrs. Truitt published three autobiographical books, each subtitled The Journal of an Artist, that explored her views on womanhood, aging and art in prose as polished and precise as the surfaces of her sculptures.

"I've struggled all my life to get maximum meaning in the simplest possible form," she said in an interview with The Washington Post in 1987. "That's what I've spent my life doing, and it's never been understood."

She was finally gaining the recognition many in the art world thought was her due. In the past five years, she had no fewer than 17 exhibitions throughout the country, including at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and Hirshhorn Museum. One of her sculptures is on display at the recently reopened Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her work is in the permanent collections of many leading museums, including the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of Art in New York.

"In the last seven years, her achievements have become more and more acknowledged," said Danese, who met Mrs. Truitt in 1968. "A lot of people understood that Anne was a seminal figure in her early days."

Anne Dean Truitt was born in Baltimore on March 16, 1921, and grew up in Easton, on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Her eyesight was so poor when she was a child that until she got glasses she didn't realize trees had individual leaves. She saw them as large masses of color and form, which some critics have suggested was an influence on her later work.

In her late teens, she was sent to North Carolina to recover from a burst appendix and spent a summer playing volleyball with the writer and 1920s cultural celebrity Zelda Fitzgerald, who was a patient at a nearby psychiatric hospital.

Mrs. Truitt graduated in 1943 from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania with a degree in psychology. She worked in psychiatric research in Boston and as a volunteer nurse's aide for the Red Cross, treating soldiers returning from World War II. She soon left psychology for art because, in her words, "the clearest beacons of aspiration that I had in my own life, I found in the work of artists -- writers as well as sculptors and painters."

She was immensely well-read and casually dropped references to Homer, Marcel Proust, William Faulkner and Willa Cather in everyday conversation. She could quote the Roman poet Ovid from memory. She had recently reread Russian novelists, including one of her favorites, Leo Tolstoy.

But her imagination was most fully engaged by color and shape. In her third volume of journals, "Prospect" (1996), she wrote, "When I swept wide brushes over large areas, I felt profoundly attuned to both structure and paint, as if I were doing what I had been born to do."

In 1961, she discovered her mature style, creating standing rectangular sculptures painted in subtle, precisely shaded colors. Set on slightly recessed bases, they appear to hover just above the floor. She was immediately identified with the emerging minimalist movement.

"If any one artist started or anticipated Minimal Art," the influential art critic Clement Greenberg wrote in 1968, "it was she."

Yet Mrs. Truitt resisted the connection because her work was painstakingly made by her own hand rather than through the industrial processes that are the hallmark of minimalism.

"I have never allowed myself, in my own hearing," she told The Post in 1987, "to be called a minimalist." She also resisted being identified as a member of the Washington Color School of the 1960s and 1970s.

She spent almost four years in Japan in the 1960s when her husband, James Truitt, was Tokyo bureau chief of Newsweek. After trying other styles in Japan, she destroyed all her experimental artwork and soon returned to her wooden sculptures.

Mrs. Truitt received many awards through the years, including a Guggenheim fellowship and five honorary doctorates. In 1984, she was acting director of Yaddo, the artists' retreat in New York.

She and her husband, a former vice president of The Washington Post, were divorced.

Survivors include three children, Alexandra Truitt of South Salem, N.Y., Mary McConnell Truitt of Annapolis and Sam Truitt of Brooklyn, N.Y.; two sisters; and eight grandchildren.

"Artists have no choice but to express their lives," Mrs. Truitt wrote. "They have only . . . a choice of process. This process does not change the essential content of their work in art, which can only be their life."

References

(1) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 23

(2) Anne Truitt, interview with Anne Louise Bayly, Archives of American Art (April - August, 2002)

(3) Matt Schudel, The Washington Post (25th December, 2004)

(4) Anne Truitt, interview with Anne Louise Bayly, Archives of American Art (April - August, 2002)

(5) Anne Truitt, interview with Anne Louise Bayly, Archives of American Art (April - August, 2002)

(6) Matt Schudel, The Washington Post (25th December, 2004)

(7) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 129

(8) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 130

(9) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 125

(10) Matt Schudel, The Washington Post (25th December, 2004)

(11) Anne Truitt, interview with Anne Louise Bayly, Archives of American Art (April - August, 2002)

(12) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 129

(13) Anne Truitt, Turn, The Journal of an Artist (1986) page 35

(14) Charles Bartlett, interview with Peter Janney (10th December, 2008)

(15) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 193

(16) Leo Damore, interviewed by Peter Janney (February, 1992)

(17) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 193

(18) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 263

(19) Ben Bradlee, The Good Life (1995) pages 258-262

(20) Peter Janney, Mary's Mosaic (2012) page 72

(21) Nina Burleigh, A Very Private Woman (1998) page 267

(22) Ben Bradlee, The Good Life (1995) page 267

(23) Cicely Angleton, interviewed by Nina Burleigh (1996)

(24) Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, New Times (9th July, 1976)

(25) Joseph Trento, Secret History of the CIA (2001) pages 280-282

(26) Anne Truitt, Daybreak, The Journal of an Artist (1986) page 200

(27) Matt Schudel, The Washington Post (25th December, 2004)

(28) Anne Truitt and Cicely Angleton, letter to the New York Times Book Review (5th November, 1995)