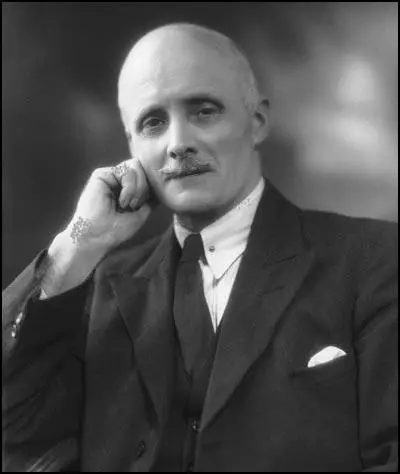

Arthur Pugh

Arthur Pugh, the fifth child of William Pugh and his wife, Amelia Adlington Pugh, was born on 19th January 1870, at Ross-on-Wye. Both his parents died when he was a child. He went to his local elementary school and at thirteen was apprenticed to a butcher. In 1894 he moved to Neath in Wales and found work in the steel industry. (1)

After his marriage to Elizabeth Morris he became a smelter at the Frodingham Iron Works in Lincolnshire. He became active in the British Steel Smelters' Association (BSSA) and eventually became a branch secretary. In 1906 he became a full-time union official. Soon afterwards, John Hodge, was elected as the Labour Party MP for Gorton in Manchester. Pugh now replaced him as general secretary of the BSSA. (2) Hamilton Fyfe, the editor of the Daily Herald, was never convinced by him as a committed trade unionist and that given different circumstances "he would have made a fortune as a chartered accountant". (3)

Arthur Pugh and the General Strike

In 1917 the BSSA became the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation. In 1920 Pugh was elected to the parliamentary committee of the Trade Union Congress, and six years later became its chairman. Later that year he replaced the left-winger Alonzo Swales as chairman of the TUC's Special Industrial Committee (SIC). This job became very important during the General Strike that began on 3rd May, 1926. The TUC adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (4)

John Hodge believed that Pugh was ambivalent about the dispute. "I have never heard him say that he was in favour of it, but I have never heard him say that he was against it." (5) Paul Davies, went further and claimed that Pugh was a reluctant participant in this conflict: "Pugh confessed that the SIC had no policy with which to conduct negotiations. The SIC reluctance to prepare was based on a complex mixture of moderation, defeatism and realism, but above all fear: fear of losing, fear of winning, fear of bloodshed, fear of unleashing forces that union leaders could not control." (6)

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the TUC, was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry.

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (7)

Herbert Smith, the President of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (8)

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (9)

Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it." (10)

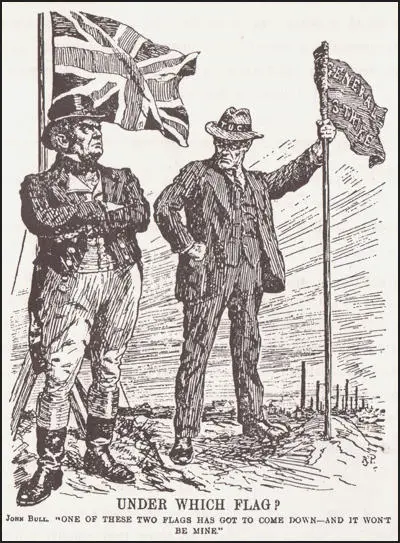

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (11)

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (12)

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work." (13)

Seven Month Lockout

Arthur Pugh and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. Arthur J. Cook, the general secretary of the MFGB, asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine". (14)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (15)

Arthur J. Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude." (16)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (17)

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a it again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (18)

Later Life

Pugh retired as secretary of the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation in 1937. He remained active in politics and helped to administer the Daily Herald. He also joined the British delegates on the economic consultative committee of the League of Nations. On the outbreak of the Second World War he served on the Central Appeal Tribunal under the Military Service Acts. In 1951 he published a history of the metal unions, Men of Steel (19).

Arthur Pugh died on 2nd August 1955.

Primary Sources

(1) Christopher Farman, The General Strike: Britain's Aborted Revolution? (1972)

It was not until 27th April, with three days to go before the mining subsidy ended, that the Council considered for the first time the problem. of what was actually to be done. Meanwhile, it was left to the Industrial Committee, originally set up to liaise with the miners in July 1925, and reappointed at Scarborough, to handle the situation as it thought best.

This committee was presided over by Arthur Pugh, chairman of the General Council... An ex-steel smelter, Pugh typified many of the older and more conservative trade union leaders. Cautious and sceptical, he regarded the political wing of the Labour movement as a potential threat to the independence and integrity of the trade unions. Of the Industrial Committee's seven remaining members, only Alonzo Swales, of the engineers, George Hicks, of the bricklayers, and John Bromley, of the locomotive engineers and firemen, were avowed Left-wingers.

(2) G. A. Phillips, Arthur Pugh : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Arthur Pugh's widening sphere of activity reflected the expanding role of the union movement in government. He was Labour representative on several public inquiries into industrial disputes, and on others considering the application of ‘safeguarding’ duties. He joined the British delegates on the economic consultative committee of the League of Nations, and in 1939, in retirement, served on the Central Appeal Tribunal under the Military Service Acts. On behalf of the TUC he oversaw the educational facilities provided for union members, and for many years helped to administer the Daily Herald. It was these various services which earned him a knighthood in 1935. The role he played in the general strike of 1926 was, by contrast, relatively unimpressive. Though acting ex officio as the chief public spokesman of the general council he was almost certainly a reluctant participant in this conflict... He made little contribution to the organization of the strike, though he was more heavily involved in the discussions with Viscount Samuel which brought it to an end. He was similarly supportive, over the next two or three years, of the TUC's attempts to launch negotiations with national employers' organizations.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)