Herbert Smith

Herbert Smith was born in the workhouse at Great Preston, Kippax, in Yorkshire, on 17th July 1862. His father had been killed in a mining accident a few days earlier and his mother died shortly afterwards. (1) He remained at the workhouse until he was adopted by a childless couple, Samuel Smith, also a miner, and his wife, Charlotte Smith. (2)

At ten years of age he started work in the mine at Glass Houghton. He became active in the union. Smith was also a talented boxer and was "a title-holding prize fighter during his youth in the Yorkshire coalfields". (3)

At a conference on 26th November 1889, Herbert Smith, Keir Hardie, Thomas Burt, Ben Pickard, Sam Woods, Thomas Ashton and Enoch Edwards formed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). Officers elected included Pickard (president), Woods (vice-president), Edwards (treasurer) and Ashton (secretary). It initially had 36,000 members. (4)

In 1894 Herbert Smith was chosen as checkweighman by the miners, and as a delegate to the Yorkshire Miners' Association. In 1897 Smith joined the Independent Labour Party and in 1902 he was appointed to the joint board of the South and West Yorkshire Coalowners and Workmen. He became president of the Yorkshire Miners' Association in 1906. Smith stood unsuccessfully as a Labour Party candidate at the general election in January 1910. (5)

Triple Industrial Alliance

In 1914 Herbert Smith played an important role in the meetings between the MFGB and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the National Transport Workers' Federation (later the Transport & General Workers Union). In April 1914 the three unions decided to form a Triple Industrial Alliance. It was a step toward "one-big-union" and toward industrial action of such a "magnitude that it could pose a straightforward challenge to State power." (6)

George Dangerfield, the author of The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) wrote: "In July, the coal-owners declared that they could no longer pay their district minimum day-wage of 7s. - that they would be obliged to reduce it, in most localities, to 6s. To the miners' rank and file this was the final challenge. It was evident that the Miners' Federation of Great Britain would take issue with the Scottish coal-owners; that the transport workers and railwaymen would join in; and that - in September or, at latest, October - there would be an appalling national struggle over the question of the living wage." (7)

First World War

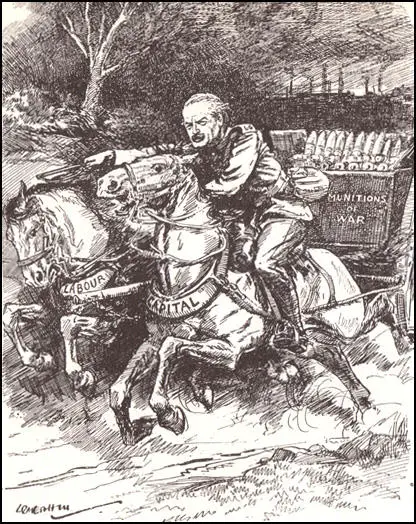

The strike did not take place because of the outbreak of the First World War. It was very important for the government to avoid strikes during the war and with the help of the Labour Party and the Trade Union Congress an "Industrial Truce" was announced. A further agreement in March 1915, committed the unions for the duration of hostilities to the abandonment of strike action and the acceptance of government arbitration in disputes. In return the government announced its limitation of profits of firms engaged in war work, "with a view to securing that benefits resulting from the relaxation of trade restrictions or practices shall accrue to the State". (8) A. J. P. Taylor, has described these measures as "war socialism". (9)

At the beginning of the war miners were the largest single group of industrial workers in Britain. Coal production increased during the first few months of the conflict. This was mainly due to a greater commitment of the labour force in maximizing output. However, by March 1915, 191,170 miners joined the armed forces. "This was 17.1 per cent of the men engaged in the industry at the beginning of the war and constituted approximately 40 per cent of the miners of military age, 19-38." (10)

The Munitions of War Act was passed by Parliament in 1915 and provided for compulsory arbitration and virtually prohibited all strikes and lockouts. The Act also prohibited any change in the level of wages and salaries in "controlled" establishments without the consent of the Minister of Munitions. In those industries important to the war effort, it forbade workers in those establishments to leave their job without a "certificate of leave". The Labour movement was strongly opposed to this measure but was endorsed by the leadership of the TUC and the Labour Party. (11)

In March 1915 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) demanded a twenty per cent wage increase to compensate for inflation. The coal owners refused to discuss a national wage rise, and negotiations reverted to the districts. Agreements were arrived at satisfactorily in most areas, but in South Wales the owners were only willing to offer ten per cent. In July the miners in South Wales went on strike. (12)

Walter Runciman, the President of the Board of Trade, met with miners leaders but was unable to obtain an agreement. H. H. Asquith, considered using the Munitions of War Act, which effectively made strike action illegal. David Lloyd George warned against this and he negotiated a settlement that quickly conceded nearly all of the miners demands. This included a 18½ per cent wage increase. (13)

Lloyd George now made regular visits to British mining areas giving patriotic speeches about the importance of coal for the war effort and stressing that the miners should work harder in order to maximize output. He argued that "every extra wagon load would bring the war to a more speedy conclusion". In one speech he pointed out: "In peace and war King Coal is the paramount lord of the industry... In wartime it is life for us and death for our foes." (14)

In November 1916, another strike over pay took place in Wales. This time the government agreed to Runciman's proposal that "the government by regulation under the Defence of the Realm Act assume power to take over any of the collieries of the country, the power to be exercised in the first instance in South Wales". It was decided to take full control over shipping, food and the coal industry. Alfred Milner was appointed as Coal Controller. It has been argued that "instigating control of one of Britain's major staple industries was an unprecedented move by the state." (15)

Milner issued his first report on 6th November 1916 and recognizing the gravity of the problem by recommending the immediate freezing of coal prices and suggesting the establishment of a Royal Commission to considering the future of the coal industry. Lloyd George argued that "the control of the mines should be nationalized as far as possible". (16) He acknowledged that this was a new political development and commented that the government had a choice, it needed "to abandon Liberalism or to abandon the war". (17)

President of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain

In 1922 Herbert Smith was elected as president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain. At a Special Conference on 18th March, Smith and Frank Hodges, general secretary of the MFGB, favoured a temporary return to district agreements so that area associations would be free to negotiate the best terms possible. Arthur J. Cook, a new member of the executive called for national negotiations. Smith was outvoted and commented that this was "a declaration of war". (18)

Frank Hodges was elected for Litchfield in the 1923 General Election. Under the rules of the union he now had to resign his post but he initially refused. It was not until he was appointed as Civil Lord of the Admiralty in the Labour Government that he agreed to go. However, his time in Parliament did not last long and he was defeated in the 1924 General Election. (19)

Arthur Cook went on to secure the official South Wales nomination and subsequently won the national ballot by 217,664 votes to 202,297. Fred Bramley, general secretary of the TUC, was appalled at Cook's election. He commented to his assistant, Walter Citrine: "Have you seen who has been elected secretary of the Miners' Federation? Cook, a raving, tearing Communist. Now the miners are in for a bad time." However, his victory was welcomed by Arthur Horner who argued that Cook represented “a time for new ideas - an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure”. (20)

Margaret Morris has argued that "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (21)

Red Friday

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (22)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (23) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (24)

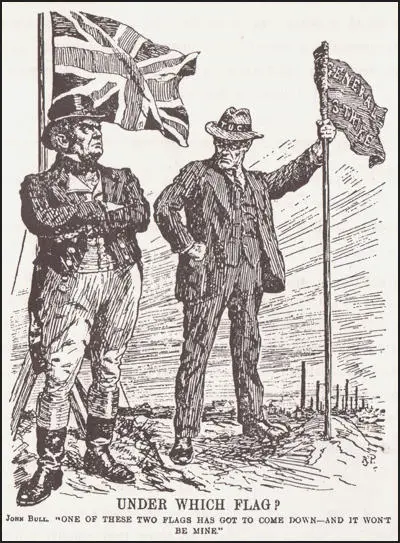

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the National Union of Mineworkers, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (25)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (26)

Herbert Smith pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation." (27)

Samuel Royal Commission

The Royal Commission was established under the chairmanship of Sir Herbert Samuel, to look into the problems of the Mining Industry. The commissioners took evidence from nearly eighty witnesses from both sides of the industry. They also received a great mass of written evidence, and visited twenty-five mines in various parts of Great Britain. The Samuel Commission published its report on 10th March 1926. Interest in it was so great that it sold over 100,000 copies. (28)

The Samuel Report was critical of the mine owners: "We cannot agree with the view presented to us by the mine owners that little can be done to improve the organization of the industry, and that the only practical course is to lengthen hours and to lower wages. In our view huge changes are necessary in other directions, and the large progress is possible". The report recognised that the industry needed to be reorganised but rejected the suggestion of nationalization. However, the report also recommended that the Government subsidy should be withdrawn and the miners' wages should be reduced. (29)

Herbert Smith rejected the Samuel Report and told a meeting with representatives of the colliery owners: "We are willing to do all we can to help this industry, but it is with this proviso, that when we have worked and given our best, we are going to demand a respectable day's wage for a respectable day's work; and that is not your intention." He added: "Not a penny off the pay, not a second on the day." (30)

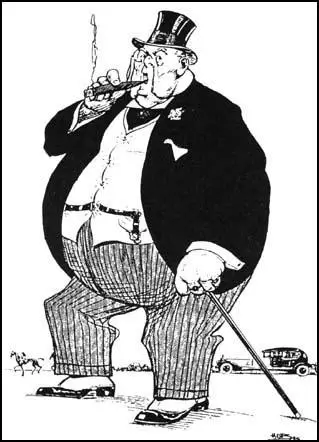

Trade Union Unity Magazine (1925)

The National Union of Mineworkers was put in a difficult position when Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), welcomed the Samuel Report as a "wonderful document". Arthur J. Cook, at the MFGB conference advised delegates not to reject the report outright, so as not to jeopardise the support of the TUC. He was aware of the need to appear reasonable, but he also reaffirmed his opposition to wage reductions: "I am of the opinion we have got the biggest fight of our lives in front of us, but we cannot fight alone." (31)

Cook toured the mining areas in an attempt to gain support for the proposed strike. It is claimed that he made as many as six speeches a day in an attempt to keep up the spirits of the miners. One former miner remembered: "Never were such vast crowds seen in the coalfields – perhaps never in Britain – as that which the Miners’ General Secretary, Mr. A.J. Cook addressed... He got, and held, the crowds. It was unusual to have a miners’ official going through the coalfields in this way... That Mr. Cook was a subject of great devotion was undeniable. He was a prophet among them. To this day men speak of those gatherings with awe." (32)

Arthur Horner later recalled: "We spoke together at meetings all over the country. We had audiences, mostly of miners, running into thousands. Usually I was put on first. I would make a good, logical speech, and the audience would listen quietly, but without any wild enthusiasm. Then Cook would take the platform. Often he was tired, hoarse and sometimes almost inarticulate. But he would electrify the meeting. They would applaud and nod their heads in agreement when he said the most obvious things. For a long time I was puzzled, and then one night I realised why it was. I was speaking to the meeting. Cook was speaking for the meeting. He was expressing the thoughts of his audience, I was trying to persuade them. He was the burning expression of their anger at the iniquities which they were suffering." (33)

Kingsley Martin, a journalist with the Manchester Guardian, was a supporter of the miners but was not convinced that Cook was the best person to negotiate an end to the dispute: "Cook made a most interesting study - worn-out, strung on wires, carried in the rush of the tidal wave, afraid of the struggle, afraid, above all, though, of betraying his cause and showing signs of weakness. He'll break down for certain, but I fear not in time. He's not big enough, and in an awful muddle about everything. Poor devil and poor England. A man more unable to conduct a negotiation I never saw. Many Trade Union leaders are letting the men down; he won't, but he'll lose. And Socialism in England will be right back again." (34)

David Kirkwood, took a different view of the general secretary of the MFGB: "The purpose of the General Strike was to obtain justice for the miners. The method was to hold the Government and the nation up to ransom. We hoped to prove that the nation could not get on without the workers. We believed that the people were behind us. We knew that the country had been stirred by our campaign on behalf of the miners. Arthur Cook, who talked from a platform like a Salvation Army preacher, had swept over the industrial districts like a hurricane. He was an agitator, pure and simple. He had no ideas about legislation or administration. He was a flame. Ramsay MacDonald called him a guttersnipe. That he certainly was not. He was utterly sincere, in deadly earnest, and burnt himself out in the agitation." (35)

The Daily Mail Strike

Stanley Baldwin and his ministers had several meetings with both sides in order to avoid the strike. Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, pointed out: "It is possible not to feel the contrast between the reception which Ministers give to a body of owners and a body of miners. Ministers are at ease at once with the former, they are friends jointly exploring a situation. There was hardly any indication of opposition or censure. It was rather a joint discussion of whether it was better to precipitate a strike or the unemployment which would result from continuing the present terms. The majority clearly wanted a strike." (36)

Considering themselves in a position of strength, the Mining Association now issued new terms of employment. These new procedures included an extension of the seven-hour working day, district wage-agreements, and a reduction in the wages of all miners. Depending on a variety of factors, the wages would be cut by between 10% and 25%. The mine-owners announced that if the miners did not accept their new terms of employment then from the first day of May they would be locked out of the pits. (37)

At the end of April 1926, the miners were locked out of the pits. A Conference of Trade Union Congress met on 1st May 1926, and afterwards announced that a General Strike "in defence of miners' wages and hours" was to begin two days later. The leaders of the Trade Union Council were unhappy about the proposed General Strike, and during the next two days frantic efforts were made to reach an agreement with the Conservative Government and the mine-owners. (38)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party refused to support the General Strike. MacDonald argued that strikes should not be used as a political weapon and that the best way to obtain social reform was through parliamentary elections. He was especially critical of A. J. Cook. He wrote in his diary: "It really looks tonight as though there was to be a General Strike to save Mr. Cook's face... The election of this fool as miners' secretary looks as though it would be the most calamitous thing that ever happened to the T.U. movement." (39)

Despite, this view, Smith fully supported Cook in the negotiations. Both men had privately stated their willingness to accept temporary wage reductions for better-paid men, however they were opposed to reductions in basic rates and insisted on completely national arrangements. Finally, they both rejected the idea of a seven-and-a-half-hour day. As Sir Herbert Samuel pointed out: "As far as the Miners' Federation is concerned it is Herbert Smith, and not Cook, who is the dominating influence, and his position is up to the present quite immovable." (40) One newspaper claimed that Smith's "unyielding, uncompromising nature.... perhaps lessened his effectiveness as a union leader". (41)

The Trade Union Congress called the General Strike on the understanding that they would then take over the negotiations from the Miners' Federation. The main figure involved in an attempt to get an agreement was Jimmy Thomas. Talks went on until late on Sunday night, and according to Thomas, they were close to a successful deal when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations as a result of a dispute at the Daily Mail. (42)

What had happened was that Thomas Marlowe, the editor the newspaper, had produced a provocative leading article, headed "For King and Country", which denounced the trade union movement as disloyal and unpatriotic.The workers in the machine room, had asked for the article to be changed, when he refused they stopped working. Although, George Isaacs, the union shop steward, tried to persuade the men to return to work, Marlowe took the opportunity to phone Baldwin about the situation. (43)

The strike was unofficial and the TUC negotiators apologized for the printers' behaviour, but Baldwin refused to continue with the talks. "It is a direct challenge, and we cannot go on. I am grateful to you for all you have done, but these negotiations cannot continue. This is the end... The hotheads had succeeded in making it impossible for the more moderate people to proceed to try to reach an agreement." A letter was handed to the TUC negotiators that stated that the "gross interference with the freedom of the press" involved a "challenge to the constitutional rights and freedom of the nation". (44)

The General Strike

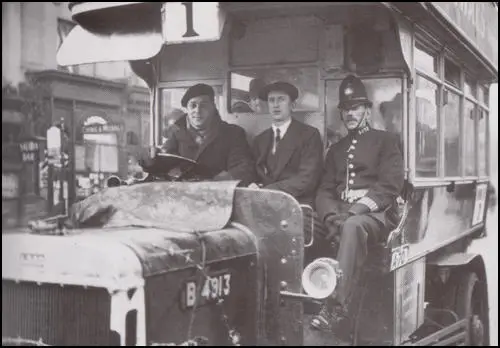

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (45)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (46)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (47)

The government relied on volunteers to do the work of the strikers. Cass Canfield, worked in publishing until the strike began. "The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble." (48)

However, most members of the Labour Party supported the strikers. This included Margaret Cole, who worked for the Fabian Research Department, pointed out: "Some members of the Labour Club formed a University Strike Committee, which set itself three main jobs; to act as liaison between Oxford and Eccleston Square, then the headquarters of the TUC and the Labour Party, to get out strike bulletins and propaganda leaflets for the local committees, and to spread them and knowledge of the issues through the University and the nearby villages." (49)

The Media and the General Strike

In his book on the the General Strike, the historian Christopher Farman, studied the way the media dealt with this important industrial dispute. John C. Davidson, the Chairman of the Conservative Party, was given responsibility for the way the media should report the strike. "As soon as it became evident that newspaper production would be affected by the strike, Davidson arranged to bring the British Broadcasting Company under his effective control... no news was broadcast during the crisis until it had first been personality vetted by Davidson... Each of the five daily news bulletins plus a daily 'appreciation of the situation', which took the place of newspaper editorials, were drafted by Gladstone Murray in conjunction with Munro and then submitted to Davidson for his approval before being transmitted from the BBC's London station at Savoy Hill." (50)

As part of the government propaganda campaign, the BBC reported that public transport was functioning again and after the first week of the strike it announced that most railmen had returned to work. This was in fact untrue as 97% of National Union of Railwaymen members remained on strike. It was true that volunteers were emerging from training and that more trains were in service. However, there was a sharp increase in accidents and several passengers were killed during the strike. Unskilled volunteers were also accused of causing thousands of pounds' worth of damage. (51)

Several politicians representing the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, appeared on BBC radio and made vicious attacks on the trade union movement. William Graham, the Labour Party MP for Edinburgh Central, wrote to John Reith, the BBC's managing director, suggesting that he should allow "a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to state the case for the miners and other workers in this crisis". (52)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, also contacted Reith and asked for permission to broadcast his views. Reith recorded in his diary: "He (MacDonald) said he was anxious to give a talk. He sent a manuscript along... with a friendly note offering to make any alterations which I wanted... I sent it at once to Davidson for him to ask the Prime Minister, strongly recommending that he should allow it to be done." The idea was rejected and Reith argued: "I do not think that they treat me altogether fairly. They will not say we are to a certain extent controlled and they make me take the onus of turning people down. They are quite against MacDonald broadcasting, but I am certain it would have done no harm to the Government. Of course it puts me in a very awkward and unfair position. I imagine it comes chiefly from the PM's difficulties with the Winston lot." (53)

When he heard the news, MacDonald, wrote Reith an angry letter, calling "for an opportunity for the fair-minded and reasonable public to hear Labour's point of view". Anne Perkins, the author of A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) has argued that if the government had accepted the proposal and people had "heard an Opposition voice would certainly have done something to restore the faith of millions of working-class people who had lost confidence in the BBC's potential to be a national institution and a reliable and trustworthy source of news." (54)

At the same time Stanley Baldwin was allowed to make several broadcasts on the BBC. Baldwin "had recognized the importance of the new medium from its inception... now, with an expert blend of friendliness and firmness, he repeated that the strike had first to be called off before negotiations could resume, but repudiated the suggestion that the Government was fighting to lower the standard of living of the miners or of any other section of the workers". (55)

In one broadcast Baldwin argued: "A solution is within the grasp of the nation the instant that the trade union leaders are willing to abandon the General Strike. I am a man of peace. I am longing and working for peace, but I will not surrender the safety and security of the British Constitution. You placed me in power eighteen months ago by the largest majority accorded to any party for many years. Have I done anything to forfeit that confidence? Cannot you trust me to ensure a square deal, to secure even justice between man and man?" (56)

By 12th May, 1926, most of the daily newspapers had resumed publication. The Daily Express reported that the "strike had a broken back" and it would be all over by the end of the week. (57) Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, was extremely hostile to the strike and all his newspapers reflected this view. The Daily Mirror stated that the "workers have been led to take part in this attempt to stab the nation in the back by a subtle appeal to the motives of idealism in them." (58) The Daily Mail claimed that the strike was one of "the worst forms of human tyranny". (59)

Negotiations with the TUC

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (60)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (61)

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (62)

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (63)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and the TUC attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (64)

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (65)

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work." (66)

Seven Month Lockout

Arthur Pugh, the President of the Trade Union Congress, and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. Arthur J. Cook asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine". (67)

Jennie Lee, was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner in Lochgelly in Scotland. During the lock-out she returned to help her family. "Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going." (68)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain." (69)

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (70)

A. J. Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude." (71)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (72)

Herbert Smith and Arthur Cook had a meeting with government representatives on 26th August, 1926. By this stage Cook was willing to do a deal with the government than Smith. Cook asked Winston Churchill: "Do you agree that an honourably negotiated settlement is far better than a termination of struggle by victory or defeat by one side? Is there no hope that now even at this stage the government could get the two sides together so that we could negotiate a national agreement and see first whether there are not some points of agreement rather than getting right up against our disagreements." (73) According to Beatrice Webb "if it were not for the mule-like obstinacy of Herbert Smith, A. J. Cook would settle on any terms." (74)

This meeting revealed the differences between Smith and Cook. "After a wary start the two seem to have developed a mutual respect during their many hours of shared stress. By the middle of the lock-out, however, they seem to have drifted on to different. wavelengths. Undoubtedly Cook felt Smith's obstinacy to be impractical and damaging. Smith, however, as MFGB President, was the Federation's chief spokesman, and Cook could not officially or openly dissociate himself from Smith's position. The MFGB special conference had granted the officials unfettered negotiating power, but Smith seems to have grown more stubborn as the miners' bargaining position worsened. One may admire his spirit, but not his wisdom. It is likely that by this time Smith reflected a minority view within the Federation Executive, but as President his position was unchallengeable, and there was no public dissent at his inflexibility. Cook, meanwhile, had embraced a conciliatory, face-saving position: he was only too aware of the drift back to work in some areas; he saw the deteriorating condition of many miners and their families." (75)

In October 1926 hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of November most miners had reported back to work. Will Paynter remained loyal to the strike although he knew they had no chance of winning. "The miners' lock-out dragged on through the months of 1926 and really was petering-out when the decision came to end it. We had fought on alone but in the end we had to accept defeat spelt out in further wage-cuts." (76)

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a it again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (77)

Herbert Smith: 1926-1938

At the end of the General Strike some people were highly critical of the way the government had used its control of the media to spread false news. This included an attack on the The British Gazette. One journalist wrote: "One of the worst outrages which the country had to endure - and to pay for - in the course of the strike, was the publication of the British Gazette. This organ, throughout the seven days of its existence, was a disgrace alike to the British Government and to British journalism." (78)

The vast majority of newspapers supported the government during the dispute. This was especially true of the newspapers owned by Lord Rothermere. The Daily Mail suggested that "the country has come through deep waters and it has come through in triumph, setting such an example to the world as has not been seen since the immortal hours of the War. It has fought and defeated the worst forms of human tyranny. This is a moment when we can lift up our head and our hearts." (79) The Daily Mirror compared the strikers to a foreign enemy: "The unconquerable spirit of our people has been aroused again in self-defence - as it was against the foreign foe in 1914." (80) The Times took a similar line arguing that the General Strike was "a fundamental struggle between right and wrong... victory was won... by the splendid courage and self-sacrifice of the nation itself." (81)

The Manchester Guardian disagreed and condemned the right-wing press for comparing strikers to a foreign enemy and urging the government to "teach the workmen the lesson they deserve". The newspaper reminded those editors like Thomas Marlowe, that many of these men had a few years earlier been praised for bravery during the First World War. It added the "comradeship" developed during the war "was a big factor in the unparalleled pacific character of this great conflict". (82)

After the strike the relationship between Smith and Cook became much worse. Cook remained defiant and argued on 28th November, 1926: "I declare publicly, with full knowledge of all that it means, that the Miners' Federation will leave no stone unturned to rebuild its forces, to remove the eight hour day, to establish one union for the miners of Great Britain, and a national agreement for the mining industry... We have lost ground, but we shall regain it in a very short time buy using both our industrial and political machines." (83)

Smith blamed Cook for the defeat and he "became an intolerant and vigorous opponent of Communists and fellow-travellers" who he believed were responsible for the misery that had been caused. As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a it again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (84)

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservative s who depended on secret donations from rich men." (85)

Miners' Federation of Great Britain saw a major drop in membership. "The union was lucky to survive at all. In many places, it didn’t. At Maerdy pit, in South Wales, the proud flagship of the Federation for a quarter of a century, the owners wreaked terrible revenge. They refused to recognise the union, and victimised anyone known to be a member. In 1927 there were 377 employed members of the lodge at Maerdy; in 1928, only eight... This was not because the overall unemployment figures were falling - quite the reverse. It was just that to stand any chance of getting work, men were forced to leave the union (or the area)." (86)

In 1929 Herbert Smith resigned the MFGB presidency in protest over an agreement to lengthen mining hours, to which the Yorkshire miners were totally opposed. Smith unsuccessfully sought re-election in 1931 and 1932. However, he remained popular with many people and "a nationwide collection among miners in 1931 paid for a bust of him at the Miners' Hall in Barnsley, and for the building of several homes for aged miners to be named after him." (87)

Herbert Smith died in his Miners' Association office at 2 Huddersfield Road, Barnsley, on 16th June 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Morris, The General Strike (1976)

Herbert Smith, the President of the M.F.G.B. since 1921, was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire. Like Cook, he played up to his public image: he always wore a cloth cap to emphasize that he was a plain pitman, and he used language to match. He was caricatured in the press as never saying anything except 'nowt doing', but this was a gross exaggeration, although he certainly believed in blunt speaking. He was deeply concerned about safety in the pits and improving the lot of the miners... His approach was always pragmatic and he had a contempt for theorizing, but he was intensely class-conscious and aggressively ready to fight for his members...

Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics.

(2) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987)

The relationship between Cook and Smith is not easy to establish. After a wary start the two seem to have developed a mutual respect during their many hours of shared stress. By the middle of the lock-out, however, they seem to have drifted on to different. wavelengths. Undoubtedly Cook felt Smith's obstinacy to be impractical and damaging. Smith, however, as MFGB President, was the Federation's chief spokesman, and Cook could not officially or openly dissociate himself from Smith's position. The MFGB special conference had granted the officials unfettered negotiating power, but Smith seems to have grown more stubborn as the miners' bargaining position worsened. One may admire his spirit, but not his wisdom. It is likely that by this time Smith reflected a minority view within the Federation Executive, but as President his position was unchallengeable, and there was no public dissent at his inflexibility. Cook, meanwhile, had embraced a conciliatory, face-saving position: he was only too aware of the drift back to work in some areas; he saw the deteriorating condition of many miners and their families.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)