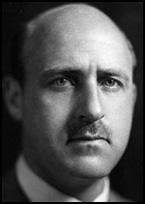

Cass Canfield

Cass Canfield, the son of Augustus Cass Canfield (1854-1904) and his wife, the former Josephine Houghteling, was born in New York City on 26th April 26, 1897. Canfield later recalled: "My father had graduated from the Columbia School of Mines and had gone on to study naval architecture in order to design his own yachts, among which the Sea Fox was the fastest ocean-going schooner of her time, winning many Atlantic races.... My mother was beautiful, determined, courageous."

Canfield was a great-grandson of Lewis Cass. In his autobiography, Up and Down and Around (1971): "Lewis Cass became Secretary of War under Jackson and later Secretary of State under Buchanan. He ran unsuccessfully for President on the Democratic ticket against Zachary Taylor.... He became a great compromiser on the slavery issue and continued to compromise until he refused to yield on the issue of Fort Sumter and was consequently dismissed as Secretary of State. President Buchanan insisted that to strengthen the garrison as Cass advised, would aggravate the friction between North and South."

Canfield attended Groton School. He later recalled: "The masters at Groton were an odd and interesting lot. At the top of the mountain stood Jehovah-Endicott Peabody; below him were many talented teachers. Among them was Ichabod Crane, a martinet who looked the part with his piercing eyes and cropped black beard. He taught mathematics and would make us stand in the corner when we were stupid. In my third-form year he presented us with a problem in geometry - Original No. 5 which stumped the whole class. But I worried at it as a dog does a bone and finally solved the puzzle; never have I experienced such a feeling of triumph. Crane complimented me and gave me confidence by saying that I would achieve what I wanted in life."

In 1915 he entered Harvard University. During this period he developed a passion for George Bernard Shaw. "His plays made a deep impression on me. Shaw, so far ahead of his time, opened my eyes to the social problems of the day." Canfield was also influenced by one of his young teachers, William L. Langer, who went on to become the author of several important history books. Canfield was also taught by Harold Laski but found him very difficult to learn from: "Laski was too clever and assumed knowledge on the part of his students which most of them lacked."

Canfield considered himself a pacifist until the sinking of the Lusitania on 7th May, 1915. He became convinced that the United States would now enter the First World War and received military training from the Harvard Regiment. He eventually joined the U.S. officers training camp in Louisville, Kentucky, but did not receive orders to go to Europe until late in 1918. Canfield was about to be sent to fight with the White Army against the Bolsheviks with the Armistice was announced.

In 1919 Canfield returned to Harvard University to complete his final year. He then moved to England where he attended New College. He later recalled that Oxford University "toned down my ebullience" but added "no one can live in that ancient, mellowed place without its having some effect." Its main impact was to develop an interest in "the best in classical and modern literature." One of the friends he made at Oxford was Anthony Eden, the future British prime minister.

On his return to New York City he found work with the New York Evening Post. Soon afterwards, the president, Edwin F. Gay, asked to see Canfield: "One day Mr. Gay called me into his office and told me that he was one of a group interested in starting a magazine of international politics because, in his opinion, there was no first-rate periodical in the field in this country. The magazine they planned to establish was the quarterly Foreign Affairs. Gay lent my services to Hamilton Fish Armstrong, the managing editor, and I was charged with raising $125,000 in order to launch the magazine and carry it for five years. This was not an appetizing assignment, but I concentrated on it doggedly. Without much effort I raised half of the total from members of the board of the Council on Foreign Relations, the publishers of Foreign Affairs-from well-known men like George IV. Wickersham, John W. Davis, Paul Warburg and Frank L. Polk, who gave me leads to their friends."

After this project Canfield went to work on the Saturday Review of Literature. "My job was to sell advertising, which I did rather successfully; it was in this way that I became acquainted with book publishing. Though I didn't usually see the top people in the publishing houses. I did learn something of their operations and became interested in the book industry." As a result he went to work for Harper & Brothers. He enjoyed the world of publishing and in 1924 he invested $10,000 in the company.

After his marriage to Katherine Temple Emmet he became manager of Harper's London office. His main task was to find English books which would be successfully published in the United States. He eventually recruited writers such as J. B. Priestley, Arnold Bennett, Harold Laski, John Haldane, Julian Huxley, E. M. Delafield, Hesketh Pearson, Shelia Kaye-Smith and Philip Guedalla. Canfield once commented: "I am a publisher - a hybrid creature: one part star gazer, one part gambler, one part businessman, one part midwife and three parts optimist."

During this period Canfield got to know Victor Gollancz: "The Gollancz office in Covent Garden looked like a barn - and still does. There Victor reigned supreme, shouting his orders to terrified girls who scurried about like frightened mice. Despite this, he was a lovable and stimulating man - an original character and in original publisher. The jackets of his books were all alike - heavy lettering on yellow paper... Although his list was a varied one, his particular interest was that of representing the intelligent Left."

Canfield was in London during the 1926 General Strike. He later recalled in Up and Down and Around (1971): "I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble. The strike dragged on for a fortnight, with apparently no end in sight. Then, one day, the skies cleared; a compromise was reached and the workers returned to their jobs. It was remarkable that no bad feeling persisted between the opposing camps in view of the fact that the Country had faced a possible revolution."

In 1934 Cass Canfield approached Hubert Knickerbocker, who had recently won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting, and suggested that he wrote a serious and comprehensive book about Europe. Knickerbocker was in the middle of another project and replied: "Try John Gunther. He's the only one with the brains, the brass, and the gusto to write the book you want." John Gunther also said he was too busy. In his book, A Fragment of Autobiography (1962) Gunther wrote: "I persisted in saying no to the project, and finally Miss Baumgarten asked me what, if any, financial advance would induce me to change my mind. To cut the whole matter off, I named the largest sum I had ever heard of - $5,000." Canfield said yes and in his autobiography, Up, Down and Around (1972) argued: "I had the strong feeling that the book would not only sell but blaze a new trail."

Gunther later recalled in the Atlantic Magazine how he did his research for the book. This included having meetings with his many contacts in Europe. "I should equip myself to be able to give information, since it's always easier to ask for something if you offer something in exchange. Journalism is really a process of barter between two people who each know something and find it to their advantage to exchange or pool their knowledge." His wife, Frances Fineman Gunther, helped him with the research and in 1935 he visited London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, Warsaw and Moscow. Gunther also met Hubert Knickerbocker who was based in Nazi Germany at the time. Knickerbocker shared his vast store of firsthand inside information on Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini.

Canfield published the book in its entirety in the United States but decided to hire three British lawyers to look at the manuscript before it was published in London. Several passages were removed including a reference to Joseph Goebbels "Goebbels never kicks a man until he's down". Another passage that was not published in Britain was the comment that Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, was the "head of a dwindling movement". The British government made it clear that they wanted nothing published if it damaged Anglo-German relations. It was the same concern that kept Winston Churchill from being allowed to appear on British Broadcasting Corporation radio programs.

The 510-page Inside Europe was published in January 1936. It included a 4,000-word profile of Adolf Hitler. As the author of Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992) has pointed out: "The profile revealed in a matter-of-fact way the bizarre character of a man who eschewed friends, money, sex, religion, and physical activity in his Machiavellian quest for unbridled power; Hitler emerged as a dangerous, unpredictable ascetic, a peasant with insatiable drives." Hitler was outraged and banned the book in Nazi Germany.

Canfield later admitted: "We figured that Inside Europe ought to sell just about 5,000 copies. That way, we'd have paid off our part of the advance and made a fairly decent profit." The first print run of 5,000 was sold out within days. The main reason for this was that the book received very good reviews. Raymond Gram Swing, writing in The Nation, pointed out that Inside Europe filled a real need at a time when America was reawakening from its self-imposed isolationism. "The vigor and almost impudent candor of this book mark it as distinctly American. I cannot imagine a man of any other nationality writing it." Lewis Gannett of the New York Herald Tribune argued that Inside Europe was the "liveliest, best-informed picture of Europe's chaotic politics that has come my way in years."

Eventually total sales reached 500,000 in the United States and Britain. Foreign sales amounted to at least 100,000. George Seldes later pointed out that other journalists respected John Gunther work: "Everybody was envious of Gunther's success. We all asked ourselves why we hadn't thought of writing the same kind of book. I guess maybe many of us had, and that's why some people felt they could have done a better job than Gunther did. But the fact was that you really had to hand it to him - he did an excellent job."

Canfield married Jane Sage White, a sculptor, who had been married to Charles Fairchild Fuller, in 1938: "Jane has been described as possessing the magic of making a cold room warm and a hot room cool... When Jane and I came together, we found in each other a likeness of rhythm and temp, an ability to live together in harmony while we each pursued our own particular interests. To be able to benefit from our earlier experiences, to be given a second chance, was a gift from the gods."

Canfield also persuaded Leon Trotsky to write a book about Joseph Stalin. He meet Trotsky for the first time in 1940: "The first impression Trotsky made was one of unusual vitality and health; he was rosy-cheeked and bouncy. I was struck with his fine brow and shock of white hair, his strong face and expressive mouth. He was neatly dressed in gray trousers and a white Russian smock.... Trotsky possessed a naturally inquisitive mind and, perhaps because of his confinement to one place, was eager to learn all he could about what was going on in the world. He asked countless questions and listened carefully to everything we said. This was a response I had never encountered before from a world figure, most of whom like to do all the talking."

During the Second World War Canfield went to work for the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW) under Henry A. Wallace: "The Board of Economic Warfare was a vital, somewhat reckless organization filled with bright people. Quite a few of them came from Henry Wallace's Department of Agriculture, which probably had more talent in it than any agency in Washington. Vice President Wallace, Chairman of the BEW, was not primarily involved in its operations - rather with broad policy. It was Milo Perkins who was the efficient operating head." After the war he became chairman of Harper & Brothers.

Canfield agreed to help Adlai Stevenson in the 1956 Presidential Election: "Later that year Lloyd Garrison, who had long been active in Democratic Party affairs, asked me whether I'd be willing to take part in the Stevenson Presidential campaign of 1956. I didn't have a ready answer. On the one hand, I liked and admired Stevenson, and I am a Democrat by persuasion. Moreover, I have long been interested in politics and have always welcomed the challenge of working in a new field. On the other hand, I knew it would be difficult, in terms of available spare time, to combine political activity with publishing. Furthermore, I hesitated, as an editor, to become involved in politics because I believe that a publisher should maintain a nonpartisan position. I debated with myself, at length, and finally concluded that in this case I was bound to help out so far as I could. Accordingly, I agreed to take on the job of chairman of the executive committee of the Volunteers for Stevenson in New York State."

Frances Stonor Saunders, the author of Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999), has pointed out that Canfield was very closely associated with the CIA and was responsible for publishing several books favourable to the organization. He also arranged for Michael Josselson to work at Harper & Brothers after being exposed as the CIA organizer of the Congress for Cultural Freedom: "Cass Canfield, one of the most distinguished of American publishers... enjoyed prolific links to the world of intelligence, both as a former psychological warfare officer, and as a close personal friend of Allen Dulles, whose memoirs The Craft of Intelligence he published in 1963."

Canfield was the author of several books, The Publishing Experience (1969), an autobiography, Up and Down and Around (1971), The Incredible Pierpont Morgan (1974), Samuel Adams' Revolution (1976), The Iron Will of Jefferson Davis (1978), Outrageous Fortunes: The Story of the Medici, the Rothschilds and J. Pierpont Morgan (1981) and The Six: Portraits of the Men Who Developed Our Early Republic into the Nation Lincoln United (1983).

Cass Canfield died in New York City on 27th March, 1986.

Primary Sources

(1) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

The masters at Groton were an odd and interesting lot. At the top of the mountain stood Jehovah-Endicott Peabody; below him were many talented teachers. Among them was Ichabod Crane, a martinet who looked the part with his piercing eyes and cropped black beard. He taught mathematics and would make us stand in the corner when we were stupid. In my third-form year he presented us with a problem in geometry - Original No. 5 which stumped the whole class. But I worried at it as a dog does a bone and finally solved the puzzle; never have I experienced such a feeling of triumph. Crane complimented me and gave me confidence by saying that I would achieve what I wanted in life.

(2) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

In San Antonio, Texas, I was put in charge of a company of regular Army cavalrymen with the assignment of training them to become artillerymen. Although I could ride tolerably, I was unable to sit a trot and must have struck those hardened soldiers, some of them Philippine veterans, as utterly unfit for command. The only thing I could do was to throw myself upon their mercies and kid them; this worked and we got on.

After a few weeks we entrained for Camp Kearney, California, near San Diego; I was posted to Battery A, 48th Field Artillery. It was a pleasant place; on weekends my two superior officers and I would set off for Coronado Beach and dance happily with the admiral's pretty daughters to the tune of "There are smiles that make us happy, there are smiles that make us blue."

In every battalion, as in any group of people, there is apt to be approximately the same proportion of bright individuals, of lazy ones, of clowns, of ambitious men, of athletes and of bad actors-and their opposites. It's remarkable how constant are these ratios.

One sunny morning the General commanding the division inspected our regiment; he asked endless questions about minute parts of the harness and the anatomy of the horse. Being a conscientious young man - I still didn't inhale cigarette smoke, in obedience to Mother's command - I'd memorized the artillery manual and so knew all the answers, but my buddies, many of them old cavalry types, did not. The General was furious and ordered all present to learn their manual at once; in addition, he insisted that the officers in the regiment, from majors down, take instruction from me in equitation. Accordingly, they had to submit to the indignity of taking orders from a green shavetail. Five hundred unbroken, wild horses from the prairies were assigned to me for training, and I had to see that they were properly fed and nursed when they were ailing. The artillery manual didn't help me here, although I did learn from the opening sentence of that holy writ that "Horses are nervous animals."

At last we got orders to proceed to Vladivostok to fight with the Czechs and White Russians against the Bolsheviks; we were about to sail when the Armistice was announced. Shortly before, the Germans, in a last desperate spring offensive, had broken through the Western front, defeating General Hubert Gough's Fifth Army, and, opening up a big gap in the line, had gained about thirty miles in a couple of days - as against the few hundred yards won by the British and French at the cost of over a million casualties in the First Battle of the Somme. Things looked grim. This was the Kaiser's last gasp, similar to the Nazi attack on Bastogne in World War II. Another disturbing event that year was the outbreak of a "flu" epidemic which swept the world and killed many civilians as well as soldiers.

We never reached the transports; orders were canceled and we were returned in due course to civilian life. Our war was over, and in a few months we were demobilized. Until the Armistice I'd never had any trouble with my battery, but thereafter the men were hard to control; everyone wanted to return home, as in all our wars. The disintegration of the armed forces was rapid, and a year after the end of the fighting our Army was almost totally demobilized.

(3) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

Anthony Eden often spoke at the many undergraduate debating societies which have traditionally been a training ground for future Prime Ministers; in preparing their papers for these debates, students took far more trouble than for their classroom assignments. Anthony eventually became Prime Minister; he still appears rather languid in manner but, obviously, has great hidden reserves of energy and ambition. Eden's Waterloo came with Suez in 1956. He was very ill at the time and left England for Panama, where he wrote me in reply to a letter I'd sent him after the debacle. lie mentioned certain mistakes he'd made over the years but said he was sure he'd been right in this instance Suez! Maybe he was, in the long run.

On another occasion, some years later, Eden made a shrewd observation to me: "If I had to deal with the Vietnam tangle, I would summon Joseph Stalin from his grave to help me negotiate, for he was the cleverest bargainer of us all."

(4) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

One day Mr. Gay called me into his office and told me that he was one of a group interested in starting a magazine of international politics because, in his opinion, there was no first-rate periodical in the field in this country. The magazine they planned to establish was the quarterly Foreign Affairs. Gay lent my services to Hamilton Fish Armstrong, the managing editor, and I was charged with raising $125,000 in order to launch the magazine and carry it for five years.

This was not an appetizing assignment, but I concentrated on it doggedly. Without much effort I raised half of the total from members of the board of the Council on Foreign Relations, the publishers of Foreign Affairs-from well-known men like George IV. Wickersham, John W. Davis, Paul Warburg and Frank L. Polk, who gave me leads to their friends. Thereafter, the spring dried up and for weeks no more money came in. Then a thought occurred to me. Why not buy from an agency - for a few dollars - a list of the thousand richest Americans and appeal to them by mail? Armstrong agreed that, while this was a very long shot, there was no harm in trying.

(5) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble. The strike dragged on for a fortnight, with apparently no end in sight. Then, one day, the skies cleared; a compromise was reached and the workers returned to their jobs. It was remarkable that no bad feeling persisted between the opposing camps in view of the fact that the Country had faced a possible revolution.

(6) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

Gunther's next book was Inside Asia. When we discussed this volume in its initial stages, I ventured the observation that, while he'd spent several years in Europe, he'd never been farther east than Beirut, where lie had stayed only a few days. He replied that he thought lie could bone up on Asia - which he did. As was his habit, lie read intensively before starting to write, and talked to academic experts as well as to people in Washington before going on his trip. At one point I introduced him to Nathaniel Peffer, a Columbia professor and an authority on the Far East, and, after a long lunch during which Gunther scribbled like mad on a big yellow pad, I suggested that lie cancel his trip to Japan because it couldn't possibly provide him with more information than he had obtained from Peffer.

Gunther was one of the most vivid characters I have ever known, and one of the most indefatigable workers. He was helped enormously by his beautiful and intelligent wife Jane, an acute observer with a gift for factual accuracy.

I remember sitting at a cafe in the Piazza San Marco in Venice and noticing a lovely young woman striding toward me, followed by a tired, droopy man; they were the Gunthers. John complained bitterly at having been dragged through the Accademia picture gallery lie was done in... A fortnight passed and the scene was repeated, in reverse. This time a bright-looking fellow walked briskly toward us, followed by a tired lady dragging her feet; the Gunthers again. During those two weeks they had been traveling in Yugoslavia, where John had interviewed scores of people. The explanation of the reversal in their roles was that the endless working sessions in Yugoslavia had acted on John like a shot of adrenalin, while Jane had found the experience utterly exhausting.

One of Gunther's remarkable qualities was his timing. Again and again it looked as if one of his Inside books would be hopelessly out-of-date by the time it was published, but there was a little alarm clock tucked away somewhere in the back of John's head which never seemed to fail him. He started Inside Europe just as Hitler was emerging as a dominant figure; he began Inside Africa when the nations of that continent were in the process of breaking away from colonization. An amazing man.

(7) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

The first impression Trotsky made was one of unusual vitality and health; he was rosy-cheeked and bouncy. I was struck with his fine brow and shock of white hair, his strong face and expressive mouth. He was neatly dressed in gray trousers and a white Russian smock. When asked how he managed to keep in such fine physical condition, he surprised me by replying in perfect English, "Oh, I go to the neighboring mountains and hunt game," which conjured up a picture of an Austrian nobleman shooting ; chamois in Franz Josef's time. In the course of talking to this highly intelligent, engaging but thoroughly dangerous character, I noticed a line of hooks on the wall behind his desk from which were hung our galley proofs of the first half of his biography of Stalin.

Trotsky was affable and provocative. The biography would be completed before many months, he assured us. He said that he had been hampered by the difficulty of obtaining reliable source material in Mexico on Stalin's life and that he got most of the information he required from friends all over the world, some of them in the Soviet Union; I had the impression of a kind of political Voltaire, conducting a vast correspondence.

One question I forgot to ask Trotsky: Just how did Lenin meet his end? I had heard from Louis Fischer, an expert on Soviet affairs, that when Lenin had fallen seriously ill, he had asked various of his political colleagues to give him poison so that lie could die quickly. One by one they refused, shocked and unbelieving. How could the Soviet Union survive without its founder, who already enjoyed a saint like status?

Commenting on Stalin's Russia, Trotsky said that lie felt that the Communist Party no longer ruled, that party officials were really rubber stamps for the bureaucracy, as under the Nazi regime. As for the war between the Soviet Union and Finland, which was still going on at that time and puzzling most observers because the Soviet forces weren't making much progress, Trotsky did not doubt the outcome - it was just a matter of time before the Finns would be overwhelmed. The slowness of the Russian advance was explainable, he said, because Stalin had purged the army of many of its best commanders; and the political commissars had such power, the officers being so fearful of them, that military movements were hampered. Also, the Soviet troops, sent to Finland from the Ukraine and southern parts of Russia, were totally unused to the conditions of winter warfare in Finland.

We talked about the world political situation. This was after the Stalin-Hitler pact, which, in Trotsky's view, Stalin had signed because he did not expect Hitler to win the war he knew was coming. Trotsky further believed that Stalin, having secured his front for a period of time, would desert Hitler at the moment of his choice. As we know, the Stalin-Hitler pact failed to achieve its purpose because Hitler attacked before Stalin could desert his Nazi ally. It is amazing how accurately Trotsky had the Nazi-Soviet situation sized up. He pictured Hitler as a master strategist, more formidable than Stalin. Nevertheless, he was confident that Germany would lose the war after a great struggle and that the United States would have to join in and save the Allies. Hitler had successfully invaded Poland when this interview took place, so Trotsky was making these observations at a time when the Nazis were looking very strong.

I asked him what he foresaw at the end of the war. "A ruined planet under American hegemony," he replied. "There will be revolution in the United States, and presumably elsewhere, coming at a time of profound economic dislocation." The British Empire was dying, in his opinion, and he prophesied that her colonies would split off as a consequence of England's lack of vitality, as shown by her policy of appeasement and the Munich reverse.

Not all of Trotsky's predictions were right, but many were; for me the visit was a telling revelation. Trotsky possessed a naturally inquisitive mind and, perhaps because of his confinement to one place, was eager to learn all he could about what was going on in the world. He asked countless questions and listened carefully to everything we said. This was a response I had never encountered before from a world figure, most of whom like to do all the talking. Trotsky spoke frankly and showed a sense of humor, as when I asked whether he would like to visit the United States. "Indeed I would," he replied promptly, "and I'd be there now if it weren't for `That Man in the White House.' Mr. Roosevelt knows enough about me so that lie wouldn't consider letting me into the country. If you had a Republican President, he would have been less well informed and I would have been able to cross your border."

I inquired what he would be doing if he were in the United States; this was like asking a safecracker what he'd do when he got out of jail. "Start a revolution, of course!" Trotsky answered.

Within a few months of this interview Trotsky was assassinated in his study by Ratnon del Rio. In the struggle with his assailant, he was pinned up against the large hooks where the proofs were hung. These proofs, spattered with Trotsky's blood, are now kept in the Houghton Library at Harvard.

With Trotsky dead, it was necessary to find a qualified person to finish the book from his voluminous notes. We chose Charles Malamuth, a Russian scholar, for this assignment, and he performed it well. In a preface he explained exactly how the biography had been prepared. So finally, after years of work, the book was finished. We sent out advance copies on a Friday morning and I breathed a sigh of relief.

The final chapter of this story is concerned with what happened forty-eight hours later, on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941- On that day the terrible news of Pearl Harbor came over the radio. After the first shock I began to think about the publishing problems presented by Trotsky's Stalin. It was obvious that, within a few days, Stalin would be America's ally and that he would deeply resent the appearance of this biography by his arch rival. On the other hand, we had an obligation to the author - in this case to his estate.

(8) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

War was approaching for the United States; the country was tense, anticipating the worst. The experts, and they were many. reported the truth as they saw it; sometimes they were right. sometimes not. There was much confusion.

Like most people I became increasingly restless, wanting something meaningful to do and not knowing what. When Mayor La Guardia called for air-raid wardens in 1939, I volunteered and was put in charge of operations in southeastern Manhattan an arduous assignment for it meant patrolling nights, in addition to working full time at the office during the day. However, I got to know the city community from housewives to undertakers, and this was a compensation. Another satisfaction was working closely with the New York police, for whom I developed considerable admiration. Most of the policemen were Irish, and were lively additions to the parties put on every couple of weeks to boost morale. Patrolman Mike Murphy, who was smart and full of initiative, could be counted on to bring gaiety to any social gathering, and it was not surprising that he rose quickly in the ranks to become New York Police Commissioner not many years later.

Across the oceans things were going from bad to worse as the Germans and Japanese advanced. Returning from a business trip the spring the Nazis were taking Paris, I crossed the Atlantic with Dorothy Thompson, the gifted newspaper commentator and wife of Sinclair Lewis. In the smoking saloon of the ship she was the center of attention, not only because she was a brilliant observer of the political scene and had just completed a survey of Swiss military power, but because she was a vivid character with a vitality which she confirmed by the proud assertion: "When I make love, the house shakes." On the ship's radio we heard, one evening, the voice of Franklin D. Roosevelt informing, and attempting to reassure, the American people about the state of American preparedness. When he'd finished, Dorothy observed that the President's figures showed that our Army and Air Force strength was about equal to that of the Swiss, a situation which we found alarming.

During this period of stress Jane and I attended a dinner dance on Long Island at the home of the John Parkinsons at which Walter Duranty, the expert on Russia and an indisputable authority on world affairs, was also a guest. As the men were having coffee and brandy, Duranty expatiated on the developing Soviet-Nazi crisis of the late spring of 1941, which he minimized. In fact, he argued convincingly that the idea of Hitler's attacking Russia was absurd. This assurance lifted our spirits and the dance went on merrily.

Later in the evening I noticed Duranty sitting at a table enjoying his champagne. In the interval since dinner a pretty young blonde with whom I was dancing had told me some interesting news and, on a wicked impulse, I beckoned to Walter and advised him to cut in on the lady. She imparted to him the report she had heard earlier on the radio that the Nazi divisions had just invaded Soviet territory. Duranty's reaction would have done justice to a George Price cartoon; he rushed from the dance floor and was off in a flash to the Times office in New York.

In such ways the experts managed to keep people shuttling between confidence and despair.

As time passed, it became apparent that the Nazis could not bomb New York; accordingly, air-raid protection became superfluous. I turned to propaganda, to promoting United States participation in the war-a worthy effort but one that, in turn, became unnecessary when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

(8) Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999)

The board of the Farfield Foundation alone provides a fascinating map of these intricate linkages. Junkie Fleischmann, its president, was a contract consultant for Wisner's OPC, and thereafter a witting CIA cover for the Congress for Cultural Freedom. His cousin, Jay Holmes, was President of the Holmes Foundation, incorporated in 1953 in New York. Holmes began making small contributions to the Congress for Cultural Freedom in 1957. From 1962, the Holmes Foundation acted formally as a pass-through for CIA money to the Congress. The Fleischmann Foundation, of which junkie was president, was also listed as a donor to the Farfield Foundation. Also on the board of the Fleischmann Foundation was Charles Fleischmann, Junkie's nephew, who was brought into the Farfield as a director in the early 1960s.

Another Farfield trustee was Cass Canfield, one of the most distinguished of American publishers. He was a director of Grosset and Dunlap, Bantam Books, and director and chairman of the editorial board of Harper Brothers. Canfield was the American publisher of The God That Failed. He enjoyed prolific links to the world of intelligence, both as a former psychological warfare officer, and as a close personal friend of Allen Dulles, whose memoirs The Craft of Intelligence he published in 1963. Canfield had also been an activist and fund-raiser for the United World Federalists in the late 1940s. Its then president was Cord Meyer, later Tom Braden's deputy, who revealed that "One technique that we used was to encourage those of our members who had influential positions in professional organizations, trade associations, or labor unions to lobby for passage at their annual conventions of resolutions favourable to our cause." In 1954 Canfield headed up a Democratic Committee on the Arts. He was later one of the founding members of ANTA (American National Theatre and Academy), reactivated in 1945 as the equivalent of the foreign affairs branch of American theatre, alongside Jock Whitney, another of the CIA's "quiet channels". Canfield was a friend of Frank Platt, also a Farfield director, and a CIA agent. In the late 1960s, Platt helped Michael Josselson get a job with Canfield at Harpers. Canfield was also a trustee of the France-America Society, alongside C. D. Jackson.

(9) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

Later that year Lloyd Garrison, who had long been active in Democratic Party affairs, asked me whether I'd be willing to take part in the Stevenson Presidential campaign of 1956. I didn't have a ready answer. On the one hand, I liked and admired Stevenson, and I am a Democrat by persuasion. Moreover, I have long been interested in politics and have always welcomed the challenge of working in a new field. On the other hand, I knew it would be difficult, in terms of available spare time, to combine political activity with publishing. Furthermore, I hesitated, as an editor, to become involved in politics because I believe that a publisher should maintain a nonpartisan position.

I debated with myself, at length, and finally concluded that in this case I was bound to help out so far as I could. Accordingly, I agreed to take on the job of chairman of the executive committee of the Volunteers for Stevenson in New York State. This was in the fall of 1955.