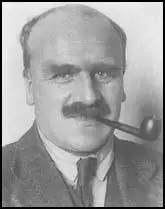

John Haldane

John Burdon Haldane, the son of a physiologist, John Scott Haldane, and the brother of Naomi Mitchison, was born in Oxford on 1st November, 1892.

Educated at Dragon School and Eton College he won a mathematical scholarship to Oxford University and obtained a first class honours degree in 1912. He then switched to science and carried out research into genetics.

On the outbreak of the First World War Haldane joined the British Army. He was initially a Bombing Officer for the Third Battalion of the Black Watch before becoming a Trench Mortar Officer in the First Brigade. While in the army Haldane became a socialist. He wrote at the time: "If I live to see an England in which socialism has made the occupation of a grocer as honourable as that of a soldier, I shall die happy."

In the summer of 1915 he was wounded and was sent back to England. After recovering he helped train new recruits in the use of grenades. In 1916 he rejoined the Black Watch in Mesopotamia but later that year he was injured by an exploding bomb and was taken to India to recover.

After the war he returned to his research at Oxford University before becoming a lecturer in Biochemistry at Cambridge University in 1922. He also conducted research on enzymes and the mathematics of natural selection and published a best-selling book called Daedalus, Or Science and The Future (1924).

In 1924 Haldane was interviewed by Charlotte Burghes, a journalist working for the Daily Express. They soon became close friends and in October 1925 they set up the Science News Service, an agency syndicating articles by them on the latest scientific discoveries. These articles appeared in national newspapers and helped to educate people about modern science.

In order to obtain a divorce from her husband, Charlotte Burghes arranged with a private detective to spend the night with John Haldane at the Adelphi Hotel in London. On 20th October 1925 Jack Burghes successfully obtained a divorce on the grounds of adultery. The case received national publicity and as a result Haldane was dismissed from his post at Cambridge University for "gross immorality". The couple were married on 11th May 1926.

Over the next few years Haldane published a series of books including Animal Biology (1927), Possible Worlds (1927) and Science and Ethics (1928). Along with his close friend, the physicist John Bernal, Haldane became convinced that the world's problems could only be solved if scientists had greater influence over government policy. He argued: "If we are to control our own and one another's actions as we are learning to control nature, the scientific point of view must come out of the laboratory and be applied to the events of daily life. It is foolish to think that the outlook which has already revolutionized industry, agriculture, war and medicine will prove useless when applied to the family, the nation, or the human race."

In 1931 Haldane, Julian Huxley, John Cockcroft, John Bernal and sixteen other British scientists visited the Soviet Union. While there they had meetings with Nickolai Bukharin and other government leaders.

In 1932 Haldane was elected to the Royal Society and the following year became Professor of Genetics at University College in London. Three years later he showed the genetic link between haemophilia and colour blindness. Haldane also carried out research into how the regulation of breathing in man is affected by the level of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream. Books by Haldane during this period included The Inequality of Man (1932), Fact and Faith (1934), Heredity and Politics (1938) and Science in Everyday Life (1939).

During this period Haldane became heavily involved in left-wing politics. He was particularly concerned about the emergence of fascism in Germany and Italy. In 1933 he travelled to Spain where he gave his support to the Socialist Party (PSOE) and the Communist Party (PCE) in its struggle with the Falange Española and other extreme right-wing parties.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Haldane supported the Popular Front government and was highly critical of the British government's non-intervention policy. Haldane and his wife, Charlotte Haldane, both joined the Communist Party and were active in raising men and money for the International Brigades.

In May 1937 Charlotte Haldane joined with Duchess of Atholl, Eleanor Rathbone, Ellen Wilkinson and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the British Battalion in Spain. Whereas Haldane became chairman of the editorial board of the Daily Worker.

In August 1941 Charlotte Haldane began work as a war reporter in the Soviet Union the Daily Sketch. She was shocked at the level of censorship taking place under Joseph Stalin. For example, she discovered that the Russian people had not been told that England was being bombed by the Luftwaffe.

Disillusioned by what she saw in the Soviet Union, Charlotte left the Communist Party when she returned to London in November 1941. She later wrote that membership of the party and affected her journalism: "I had lied, cheated, acted under false pretenses, obeyed and carried out orders from on high, denied all my inner ethical tenets and spiritual codes for the good of the cause, convincing myself that the end justified the means."

By this time their relationship had broken down and Haldane obtained a divorce from his wife in November 1945. He remained a member of the Communist Party and was a regular contributor to the Daily Worker.

In 1948 questions were asked in the House of Commons about whether communists like Haldane had access to official secrets. Haldane was quick to defend himself against these attacks. On 15th March 1948 he said: "I certainly am a Communist - as good a Communist as anyone. I am working on two Government scientific committees, one of which deals with under-water physiology. They don't pay me anything and they can throw me off them if they want to. But if they'd thrown me off six months ago, they might not have had certain increased efficiency in under-water craft. They can go on sacking people, but the only result will be that all sorts of people will be denounced as Communists when they are not. If I got orders from Moscow I would leave the Communist party forthwith."

Haldane continued to work closely with scientists in the Soviet Union. However, there was a purge of Soviet scientists after the Second World War. Haldane's great friend, Nikolai Vavilov, Head of the Institute of Genetics, was dismissed and sent to Siberia where he died. Haldane was appalled by this interference in science and in 1950 left the Communist Party.

In 1957 Haldane emigrated to India in protest at the Anglo-French invasion of Suez. He worked at the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta before becoming head of the Orissa State Genetics and Biometry Laboratory in 1962. John Burdon Haldane died in 1964.

Primary Sources

(1) J. B. S. Haldane, Daedalus, Or Science and The Future (1924)

The biologist is the most romantic figure on earth. With the fundamentals of ectogenesis in his brain, the biologist is the possessor of knowledge that is going to revolutionize human life.

(2) Charlotte Haldane, first met John Haldane in 1924 when she interviewed him for the Daily Express. She wrote about the meeting in her autobiography, Truth Will Out (1949)

He seemed larger than life. He had a huge domed balding head, almost completely spherical. His forehead protruded over the fiercely bushy eyebrows and when he frowned it wrinkled into rows of corrugated ridges. His eyes were blue and blazing. His nose was bold and Roman. (Beneath it was a thick moustache), but then the face somehow dwindled away into a weak little mouth and jaw. It was a face of extraordinary contradiction. He had a rather thin, reedy, stammery voice. There was, in fact, very little conversation, for when he talked it was like listening to a living encyclopedia.

(3) J. B. S. Haldane, Possible Worlds (1927)

Until the scientific point of view is generally adopted our civilization will continue to suffer from a fundamental disharmony. Its material basis is scientific, its intellectual framework is pre-scientific. If we are to control our own and one another's actions as we are learning to control nature, the scientific point of view must come out of the laboratory and be applied to the events of daily life. It is foolish to think that the outlook which has already revolutionized industry, agriculture, war and medicine will prove useless when applied to the family, the nation, or the human race."

(4) Fred Copeman, Reason in Revolt (1948)

Professor J. B. S. Haldane arrived on a visit. He decided to stay for a week in the front line. It was impossible not to be affected by the sincerity of this man. He was one of the greatest living scientists, intensely shy, and yet capable of expressing the most intricate problem in simple language. One night Bulger introduced a discussion. Bulger was an

ex-army officer, known as " the Admiral", I assume because of his Oxford accent. He was always ready for an argument, his special subject being women. The discussion started on the usual lines - a reference to somebody who had bled a lot on the previous day during a small scuffle, and developing towards the inevitable subject of women. He finished up with his own theory of telegony. Haldane had only just arrived, and very few knew who he was. "The Admiral" propounded his ideas in all the lurid language he could produce, until the professor quietly said it was a lot of bunk. " No such thing existed, and science could prove that the theory had no foundation in fact," he said.

He then proceeded to explain in his simple way what really happened during the formation of a child. "The Admiral," who all evening had been sipping vino, had reached the stage where, without being actually drunk, he was at least very lively. He stamped out of the place after telling the professor just what he thought of him. I met him an hour later and told him that the fat old gentleman sitting in the corner was J. B. S. Haldane, the great biologist, and even through the booze he was profuse in his apologies.

(5) J. B. S. Haldane, speech (15th March 1948)

I certainly am a Communist - as good a Communist as anyone. I am working on two Government scientific committees, one of which deals with under-water physiology. They don't pay me anything and they can throw me off them if they want to. But if they'd thrown me off six months ago, they might not have had certain increased efficiency in under-water craft. They can go on sacking people, but the only result will be that all sorts of people will be denounced as Communists when they are not. If I got orders from Moscow I would leave the Communist party forthwith. But sometimes I wish we did get orders from Moscow. I would like to know what they are thinking. The only group of people in this country who get orders from foreign powers are Roman Catholics.