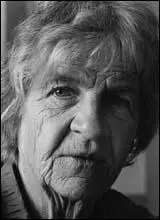

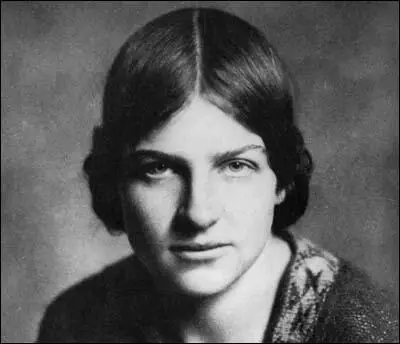

Naomi Mitchison

Naomi Haldane, the daughter of a physiologist, John Scott Haldane, and the sister of John Haldane, was born in Edinburgh on 1st November, 1897. Her mother, Kathleen (Trotter) Haldane, was a suffragist, who published the memoir, Friends and Kindred.

After being educated at Dragon School she moved to Oxford University to science but left in 1915 to become a VAD nurse during the First World War. In 1916 she married Gilbert Mitchison, while he was on leave from the Western Front.

Mitchison was horrified by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War . A passionate supporter of the Popular Front government she wrote in 1937: "There is no question for any decent, kindly man or women, let alone a poet or writer who must be more sensitive. We have to be against Franco and Fascism and for the people of Spain, and the future of gentleness and brotherhood which ordinary men and women want all over the world."

During her life Mitchison published over 70 books. This included historical novels and short-stories such as The Conquered (1923), Cloud Cuckoo Land (1925), Black Sparta (1928), The Corn King and Queen Queen (1931) and The Blood of the Martyrs (1939).

Her novel, We Have Been Warned (1935), that dealt with abortion and birth control was censored. A socialist and active member of the Labour Party, she took part in many political campaigns, including helping her husband to get elected to the House of Commons. Mitchison was also a regular contributor to the feminist journal, Time and Tide and the New Statesman.

Mitchison, who mainly lived in Carradale on the Mull of Kintyre after 1937, wrote three volumes of memoirs, Small Talk (1973), All Change Here (1975) and You May Well Ask (1979). Her diary covering the Second World War, was published as Among You Taking Notes, was published in 1985.

Later books included a book about her travels in five continents, Mucking Around (1981), A Girl Must Live (1990) and The Oathtakers (1991).

Naomi Mitchison died, aged 101, on 11th January, 1999.

Primary Sources

(1) Naomi Mitchison wrote about why she became a VAD in her autobiography All Change Here (1975)

In 1915, with Dick away I became more and more impatient with Oxford and my own non-involvement. Girls I knew had gone to do 'war work'; one or two were even in munitions factories. And at least I had passed first aid and home nursing examinations and what was more Sister Morag Macmillan had chosen me as the one to whom she could teach massage, feeling the hands of half a dozen girls and rejecting them before taking me on. Whether she knew I had some capacity as a healer which might be brought out is something else again; had she sensed that she would wisely have said nothing about it.

I nagged and nagged and finally went off to be a VAD nurse at St. Thomas's along with May Douie, an Oxford friend whom I did not know very well. I had no idea what a hospital was really like; I doubt if I had ever been inside one. Our friends and relations would never find themselves in a hospital; they went to nursing homes, especially the Acland at Oxford, though there might well be arrangements there for almost free treatment in certain cases. Some nursing homes or small, special hospitals were quite well endowed. So St. Thomas's was something of a shock; the size, the long, clattering corridors and staircases and the huge, undivided wards. Everything was, no doubt, sanitary, but there were no frills.

Of course I made awful mistakes. I had never done real manual household work; I had never used mops and polishes and disinfectants. I was very willing but clumsy. I was told to make tea but hadn't realised that tea must be made with boiling water. All that had been left to the servants.

Once when lifting a heavy patient my collar stud flew out and my stiff collar opened. Oh, dear! At that time we all wore stiff white cuffs, collar and belt into which we stuck our scissors, so much needed for bandages, dressings and sewing. One's blue skirt was ankle length with a long white apron over it. I ought to have had a proper uniform coat to go out in, but my mother had economised on that, thinking my own old one would do as well, but again I got an official scolding.

(2) Naomi Mitchison, All Change Here (1975)

Probably by the summer of 1915 many of the best sisters and nurses from St Thomas's had been drafted off to base hospitals and ambulances; we VADs were the lowest of the low in the pecking order, and those who had been trodden on were happy to tread on us. We were seldom told what was wrong with the patients and the one and only Sister who did tell us and took some trouble to explain the treatment got increased loyalty and intelligent service. I was somewhat upset at being put into a VD ward and experienced a kind of moralising dislike for the patients, as well as being extra careful over sterilising basins and thermometers.

The other thing which I found upsetting was to see a patient with his eyes closed and throat heavily bandaged, with a policeman in full uniform sitting next to him. The patient was of course a suicide attempt and this was a crime. Was he arrested as soon as he was conscious? I never knew. Both disappeared from the ward. One thing missing was the blood transfusion apparatus which is now so common in an accident ward that one takes it for granted.

(3) Naomi Mitchison, Authors Take Sides (1937)

There is no question for any decent, kindly man or women, let alone a poet or writer who must be more sensitive. We have to be against Franco and Fascism and for the people of Spain, and the future of gentleness and brotherhood which ordinary men and women want all over the world.

(4) Lena Jeger, The Guardian (13th January, 1999)

The Mitchison house at Hammersmith was famous for its parties in happy or anxious times. The guest lists covered the widest spectrum - the Huxleys, Wyndham Lewis, the Coles, Postgates, Laskis, Stracheys, E M Forster, A P Herbert, Gertrude Hermes; and always there were the unknown protégés, refugees and strange lost foreigners from all over the world.

This generous style of hospitality continued at their home at Carradale in Argyll. The large house gathered in all kinds of waifs and strays among the famous and unreproached scroungers; and then the Mitchison grandchildren and great-grandchildren joined the mix. Naomi's wartime diary, Among You Taking Notes (1985), is a vivid description of that period, and of her own pivotal role in it.

Fortunately, Mitchison was blessed with an incomparable gift of concentration. The typewriter on her desk in the crowded drawing-room at Carradale was always uncovered and she would work there busily while the guests played Scrabble, strummed guitars, a fisherman came about the salmon, a ghillie to consult about skinning a deer, or just somebody asking what was for supper.

Often Mitchison was writing letters. She gave generously of her time and trouble to people all over the world, known and unknown, including those who sent their beloved (but useless) manuscripts. Or to people like the poet Stevie Smith, who wrote out of the blue and began a long correspondence and lasting friendship. The uneasy young W H Auden treasured her letters - or, rather, he loved getting them (he never kept letters once he'd read and answered them).

Mitchison was able to write anywhere, which helped because - as a compulsive traveller - she could get on with her writing on planes or in trains. She went to the US in the 1930s, because she was worried about sharecroppers; to Vienna in 1934 when the Nazi-era storm clouds gathered, and she smuggled letters from endangered people to Switzerland in her knickers.

(5) Neil Ascherton, The Guardian (17th January, 1999)

With a Victorian faith in progress, she worked incessantly and often physically. Among other things, she was a political fire-brand, energetic farmer, Argyle county councillor and relentless freelance journalist. She discovered that the best way to get an article published was to appear in an editor's office and hold his nose to the type script. Not all enjoyed this.

On the Manchester Guardian and later the Scotsman, I was often deputed to receive her, if not actually fend her off. She knew why a junior reporter was talking to her, but was so friendly and fascinating that I always promised that her piece would go in. Not all were good, but most were: the trouble of was, she wrote so many.

There was a Fabian, Shavian flavour to her energy, she could have belonged to the 'Fellowship for a new Life'. In the post war years, Carradale became a sort of intellectual mecca for leftish men and women lucky enough to get an invitation. Her tribe had increased enormously, and in summer the house sheltered countless Mitchison descendents and friends. In the quiet drawing room, great minds hid behind newspapers or doctoral theses while armies of children poured past the windows or fought ping pong tournaments: this was a happily informal house, but private thought was not to be interrupted.

She was wise, having lived through much personal turmoil, and brave: somebody who lived out her feminism in days when love and freedom could carry grim penalties. But above all I will miss her fearless confidence.

If intelligent people shouted long and loud enough at governments, she believed, truth would prevail. She often did prevail. For the rest of us not raised in an age of reason, it is harder.