H. R. Knickerbocker

Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker, the son of Rev. Hubert Delancey and Julia Catherine Knickerbocker, was born in Yoakum, Texas, on 31st January, 1898. After graduation from Southwestern University in 1917 he served briefly with the United States Army on the Mexican border. Knickerbocker married Laura Patrick in 1918, and they had one son Conrad. (1)

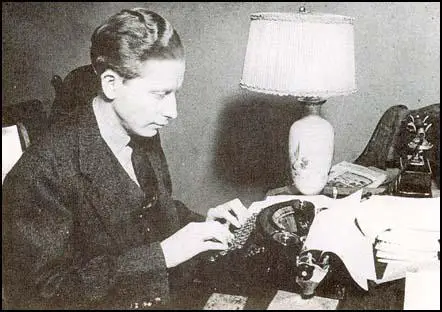

In 1919 Knickerbocker went to Columbia University to study psychiatry. The following year he became a reporter for the Newark Morning Ledger. In 1922 he moved to New York City and reported for the New York Sun. He was a "rewrite man", whose job it was to turn the information provided by the "leg-man" into copy. In 1923, still hoping to become a doctor, Knickerbocker went to Germany and matriculated at the University of Munich. To pay his way, he took a job as occasional correspondent for the United Press. (2)

On 8th November, 1923, Knickerbocker witnessed Adolf Hitler and his failed Beer Hall Putsch. For the next five weeks he attended Hitler's trial for treason and decided to return to journalism. In 1926 he began work with Dorothy Thompson. (3) Thompson's biographer, Susan Hertog, has argued in Dangerous Ambition (2011): "Her assistant Knickerbocker, a serious journalist, lacked her clout but matched her in energy, discipline, and will to succeed." (4)

The Soviet Union

Knickerbocker became the Moscow correspondent for International News Service in 1928. While in the Soviet Union Knickerbocker became a close friend of William Duranty, who worked for the New York Times. The two men began collaborating on a series of short stories. They agreed to write one a week. They then exchanged their stories and edited one another's work. The plan was to submit the stories they wrote together under Duranty's name, since it was better known than Knickerbocker's name. (5)

In 1927 Knickerbocker was posted to Berlin but they continued to write stories together. On 27th June, Duranty wrote to Knickerbocker: "I have just had a foul and bitter disappointment. That lousy bastard in New York wrote me a pompous and idiotic letter the upshot whereof was that he was sending the stories back without even trying to place any of them. I still don't really understand why, because he said they were splendidly written." According to Duranty the agent complained the stories "resembled episodes from real life rather than short stories and also deal with persons and events alien to American life." Duranty dismissed these views because it was "highbrow nonsense about the form and function of the short story... I suppose the blighter has never heard of Maupassant or disapproves of him". (6)

In November 1927, William Duranty received news that one of his stories written with Knickerbocker, The Parrot, had been accepted for publication in the women's magazine, The Redbook. Knickerbocker was overjoyed: "Upon receipt of your letter I went into a trance during which I consumed half a bottle of Scotch... By God it would be great to get out of this grind of newspaper work. Once we have sold, say, twelve in a row, we could afford to talk about throwing up our jobs. But not until then." The story only made the men $40 but it did win the respected O. Henry Award for the year's best short story. Unfortunately, it was published under Duranty's name and Knickerbocker received none of the glory. Duranty wrote a letter of apology saying it was "awfully unfair that I should get the credit alone... and I'll be glad to sign any letter to the O. Henry people you care to suggest". However, it never happened and Knickerbocker was never acknowledged as the co-author of the story. (7)

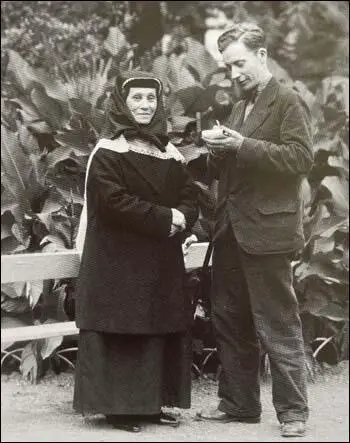

Hubert Knickerbocker became chief Berlin correspondent for the New York Evening Post and the Philadelphia Public Ledger in 1928. In the summer of 1930 he visited the Soviet Union for two months. He carried out his first interview with the mother of Joseph Stalin. She told Knickerbocker she wanted her son to be a priest. She insisted on changing into a black ceremonial dress, a black kerchief on her head and a white lace shawl around her shoulders, so that he could take her picture. (8)

Knickerbocker's critical views on the Soviet Union were generally well received in Germany. His book, The Red Trade Menace, was published in 1931. He argued that the Soviet Union would become a industrial powerhouse. Later that year he won the Pulitzer Prize for his articles describing and analyzing the Soviet Five-Year Plan. Knickerbocker wrote: "Zeal and terror are the two psychological instruments for accomplishment of the Plan… The worst offence today in the Soviet Union is to doubt the Plan. Skepticism in Bolshevik Russia is more heinous than crimes of violence." (9) Knickerbocker argued that the Soviet Union would become a industrial powerhouse. He added that what what the Soviet regime wasn't communism, certainly not as Karl Marx had envisaged it. As Deborah Cohen pointed out: "Instead it was best understood as the most extractive sort of capitalism in which all profits belonged to the state." (10)

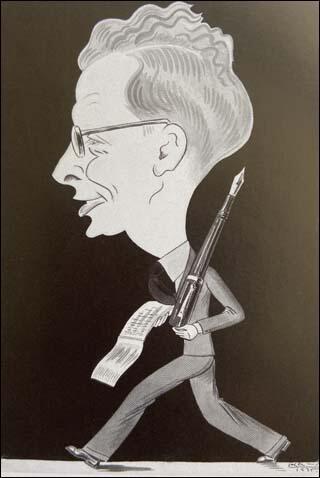

H. R. Knickerbocker became the chief foreign correspondent of the William Randolph Hearst newspaper chain. He was always known as "Red" because of his bright ginger hair. Knickerbocker was usually sent to countries expecting trouble. It was said that when he entered the lobby of a great hotel, the manager greeted him with the words "Mr Knickerbocker, welcome. Are things really so bad." (11)

Nazi Germany

Knickerbocker was very critical of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. He argued that the Jews were facing economic and social annihilation as well as a systematic campaign of physical violence. Some journalists based in the United States believed that Knickerbocker was being too subjective in his reporting. The Montclair Times accused him of getting "quite excited" about Jews and failed to depict the German perspective. His reports were "hearsay", they were exaggerated, they could scarcely be believed. "There must be two sides to the question." (12)

Knickerbocker strong opposition to the Nazi movement. however, made his position difficult when Hitler became a major political figure in 1932. Alfred Rosenberg, the foreign minister, tried to force the Philadelphia Public Ledger to recall Knickerbocker on the grounds that the man was "spreading insidious lies". Joseph Goebbels, who was still trying to change Knickerbocker's mind on fascism, immediately stepped in forcefully to countermand the order. (13)

The fact that Knickerbocker now owed his job to Joseph Goebbels didn't make him any the more respectful. At one press conference the Nazi government announced the new four classifications of women. At the top of the hierarchy were the Class One women, Aryans, blonde and blue-eyed, who would be reserved to breed with the leading Nazis. At the bottom were the Class Four women, Jews and Slavs unfit for either marriage or reproduction. Knickerbocker asked the first question: "Herr Minister, would you tell us why you wish to give all the advantages to Class Four women?" (14)

Knickerbocker did manage to get an interview with Adolf Hitler before he took power: "An interview with Hitler began normally enough, but after a few sentences, his eyes fixed on the ceiling, and he ranted through his usual litany. The German army had been stabbed in the back by profiteers on the home front. The iniquities of the Treaty of Versailles and the Allies' outrageous reparations payments. It was impossible for reporters to get a direct answer to any of the questions they posed: the mfor an just repeated his speeches." (15)

It became more difficult for Knickerbocker when the Nazis took power in 1934. (16) He upset the authorities with his articles on the Nuremberg Party Conference in September, 1934. Adolf Hitler now decided that all "hostile" foreign correspondents should be banned from Germany, even if they worked for right-wing newspapers. This included Knickerbocker, when he became one of twenty-five foreign correspondents who were expelled from Germany, while another thirty or so departed when their "safety could not be guaranteed". (17)

On his return to the United States, Knickerbocker, published, Boiling Point: Will War Come in Europe (1934). Charles G. Poore, reviewed the book for the New York Times: "The Boiling Point does give a very vivid idea of the rate at which Europe is approaching one of its perennial explosions. The main heater seems to be Adolf Hitler. And any one who says I knew that before will find a good deal of reassurance in the idea by touring around Europe with Mr. Knickerbocker and hearing the conversations he had with the gentlemen who occupy - or have recently occupied - the main chairs in the Chancelleries on Mr. Knickerbocker's beat... Mr. Knickerbocker has a fine talent for collecting them. It's a well-conducted tour, pausing for inspection at all the main danger points, and one meets celebrities at every stop." (18)

Knickerbocker was now based in London and became known as the best informed on European politics in the world. John Gunther later wrote: "I contrived (April 1935) to visit Paris, Rome, Berlin, and Moscow in those three weeks. Meanwhile colleagues helped me, Knickerbocker most of all. He knew more about Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini than any other newspaperman in Europe, and on three successive long afternoons in London he valiantly, brilliantly emptied himself of these subjects for my benefit." (19)

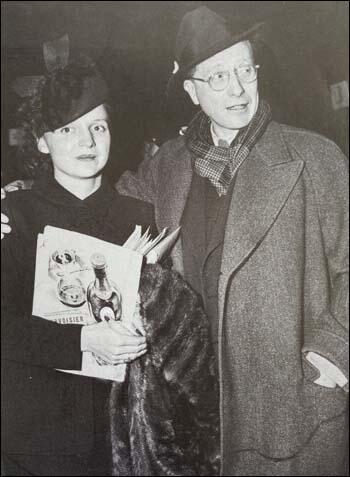

Knickerbocker first met the 18-year-old Agnes Schjoldager in Berlin 1931. He was still married to Laura Patrick and it was not until four years later that he persuaded her to consent to a divorce. Hubert and Agnes were married at the Caxton Hall registry office, with John Gunther and Francis Fineman as witnesses. (20)

Spanish Civil War

Knickerbocker also reported on the Spanish Civil War and according to Paul Preston "his articles in the Hearst press chain during the early months of the war, had done much for the Francoist cause". (21) Knickerbocker's great friend and fellow foreign correspondent, John Gunther, thought these articles were "awful" as he believed that the Republican Army was fighting for democracy. He had heard first-hand reports of Franco's massacre of thousands of Republicans in the town of Badajoz and he considered Knickerbocker's stories of atrocities was "straight out of Hearst's playbook." (22)

In August 1936 Knickerbocker wanted to join the African columns moving north from Seville, Juan Pujol, as head of the Gabinete de Prensa in Burgos, had written to General Francisco Franco recommending him as an "outstanding figure of North American journalism, who has done great work with his always accurate reports of our Movement". (23) However, Franco decided against giving him permission to be with his troops as the war was going badly for the fascist rebellion. (24)

The American Ambassador, Claude Bowers, reported to United States Secretary of State, Cordell Hull: "General Franco is becoming more and more intolerant towards war correspondents with his armies. He turned them all away when the attack on Malaga began. The men he then turned away had been with him for months and had written the most pronounced pro-Franco articles. No war correspondent with him could have been more satisfactory to him than Knickerbocker who was convinced of his early and inevitable victory when I saw him frequently five months ago.... I can only interpret this denial to mean that there must be something in the present situation that General Franco does not care to have blazoned to the world. I find Knickerbocker completely flabbergasted by the changed situation." (25)

H. R. Knickerbocker now tried to enter Spain illegally but was caught and imprisoned in San Sebastián. He later described the prison as the worst he'd ever seen, an inch of filth on the floor, blood smeared on the walls and a terrible smell. His cellmate was an anarchist who was executed that night for his political beliefs. Knickerbocker later wrote: "I realized I had never known before what the war was like." (26)

He was released after 36 hours. In April 1937 Knickerbocker interviewed Captain Gonzalo de Aguilera Munro. Aguilera claimed that Franco's forces intended to catch execute Manuel Azaña and Francisco Largo Caballero: "We are going to shoot 50,000 in Madrid. And no matter where Azaña and Largo Caballero and all that crowd try to escape, we'll catch them and kill every last man, if it takes years of tracking them throughout the world... In the interview Aguilera argued: "It is a race war, not merely a class war. You don't understand because you don't realize that there are two races in Spain - a slave race and a ruler race. Those reds, from President Azaña to the anarchists, are all slaves. It is our duty to put them back into their places - yes, put chains on them again, if you like. Modern sewer systems caused this war. Certainly because unimpeded natural selection would have killed off most of the 'red' vermin. The example of Azaña is a typical case. He might have been carried off by infantile paralysis, but he was saved from it by these cursed sewers. We've got to do away with sewers.... All you Democrats are just handmaidens of bolshevism. Hitler is the only one who knows a 'red' when he sees one... We must destroy this spawn of 'red' schools which the so-called republic installed to teach the slaves to revolt. It is sufficient for the masses to know just enough reading to understand orders... We must restore the authority of the Church. Slaves need it to teach them to behave... It is damnable that women should vote. Nobody should vote - least of all women." (27)

Knickerbocker's article was quoted extensively in the US Congress by Jerry O'Connell of Montana. (28) Paul Preston, the author of We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War (2008): has argued that Knickerbocker's "account of what sort of society the military rebels planned to establish in Spain... based on Aguilera's anti-Semitic, misogynistic, anti-democratic opinions... was a significant propaganda blow against the Francoists, coming as it did shortly after the bombing of Guernica." (29)

Second World War

Knickerbocker remained in Europe and covered critically the efforts of Neville Chamberlain to appease Adolf Hitler. His journalist friends tended to agree with him. Vincent Sheean wrote to John Gunther arguing that the betrayal of the Czechs made him sick for days. A fellow journalist, James Philip Lardner, had been killed fighting for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Sheean argued that the "Lardners of the world functioned as the antithesis to the Chamberlains" and that they represented the moral energies of ordinary people who stood for decency. "If the world has a future they have preserved it, for provinces and nations can be signed away, but youth and honor never." (30)

After the outbreak of the Second World War, in 1939 Knickerbocker moved to Paris and after the defeat of France in 1940, he settled in London and covered the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. Knickerbocker also toured the United States where he argued that "we should go into war today." His strong views on the subject appeared in his book, Is Tomorrow Hitler's? 200 Questions on the Battle of Mankind (1941). (31)

Knickerbocker returned to the United States and gave a series of lectures on the war in Europe. Time Magazine reported: "The urge which drives slight, bespectacled lecturer Knickerbocker, with his shock of wavy, flame-red hair (balding on top), is his belief that this is very much a U. S. war. He makes no secret of his Franco-British sympathies, believes the war may last six years or longer, end in a Soviet Europe. In his first lectures he called for outright U. S. intervention. Now he no longer flatly advocates intervention in his lecture; but in the question period that follows, he generally makes his conviction amply clear. So far he has told an estimated 70,000 people his belief that: 1) The Treaty of Versailles was too lenient, not too hard. 2) If Hitler wins, the U. S. will be not much better off than Czechoslovakia was in 1938, will have to face the combined fleets of Germany, Italy, Russia, Japan, England, France. 3) The U. S. should throw its whole weight behind the Allies, send no troops, but arms and money, an air force, the U. S. Navy. (32)

As Knickerbocker was a strong opponent of fascism, Ernest Cuneo, who worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and an agent of the British Security Coordination (BSC) recommended him for receiving information from British military sources. Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that Cuneo was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Knickerbocker, Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Dorothy Thompson, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Vincent Sheean, Edmond Taylor, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Ralph Ingersoll, and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America". (33)

BSC began a secret campaign against the main isolationist society, the American First Committee (AFC). The organisation was established in September 1940. The America First National Committee included Robert E. Wood, John T. Flynn and Charles A. Lindbergh. Supporters of the organization included Elizabeth Dilling , Burton K. Wheeler, Robert R. McCormick, Hugh S. Johnson, Robert LaFollette Jr., Amos Pinchot, Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, Harry Elmer Barnes and Gerald Nye. By the spring of 1941, the British Security Coordination estimated that there were 700 chapters and nearly a million members of isolationist groups. Leading isolationists were monitored, targeted and harassed. When Gerald Nye spoke in Boston in September 1941, thousands of handbills were handed out attacking him as an appeaser and Nazi lover. Following a speech by Hamilton Fish, a member of a group set-up by the BSC, the Fight for Freedom, delivered him a card which said, "Der Fuhrer thanks you for your loyalty" and photographs were taken. (34)

After Pearl Harbor Knickerbocker, joined the US Air Force, aged forty-two. He told his friend, John Gunther, "I've been a warmonger for two decades. I can't just sit around at home while American boys go abroad and get killed for Dinah and me." (35) He found military service tedious and pointless. He wanted to be transferred to the Office of Strategic Services, the intelligence agency, headed by William Donovan, and established by Franklin D. Roosevelt in July, 1942. However, his application was rejected. (36)

In 1941 he went to work for the Chicago Sun as its chief foreign correspondent in the Far East and South Pacific. The following year Knickerbocker followed Allied troops into North Africa, and acting as the official correspondent for the First Division of the United States Army. During the remainder of the war he reported from the European theater of military operations. (37)

After the war Knickerbocker went to work for radio station WOR, in Newark, New Jersey. Knickerbocker was one of thirteen prominent journalists from the US, who had been invited by the Dutch government to conduct independent investigations in the Dutch East Indies of rising tensions between the Dutch and the new independence movement in what is now Indonesia. On July 12, 1949, the journalists were on a KLM Lockheed 749 Constellation that was attempting an approach into Bombay, India, in monsoon weather and flew below the minimum safe altitude into nearby hills killing all 45 passengers aboard. It was India's worst air disaster at the time. For many years afterwards, there were conspiracy theories that the plane had been deliberately tampered with to halt the investigation. (38)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles G. Poore, New York Times, review of Boiling Point: Will War Come in Europe (3rd June, 1934)

Reading a new book by H. R. Knickerbocker is like sitting in a ship's bar with one of those fabulous Englishmen who has been everywhere and known every one and can tell you just what's the significance of everything going on. You learn a lot you didn't know before. You see he's uncommonly well informed. You get a stimulating swift pelting of ideas. But you have a feeling that his more immediate judgments are based on moving events that have already changed somewhat in the few days you have been at sea.

This book, for example, based upon a series called "Will War Come?" that appeared in the Hearst papers last February and March, was outmoded in some of its passages before it could be rushed through to publication. The man who as Prime Minister of Bulgaria had a couple of months before told Mr. Knickerbocker that "the Kingdom of Bulgaria is a democracy" had been thrown out of office by a Fascist group.

In spite of all that, The Boiling Point does give a very vivid idea of the rate at which Europe is approaching one of its perennial explosions. The main heater seems to be Adolf Hitler. And any one who says I knew that before will find a good deal of reassurance in the idea by touring around Europe with Mr. Knickerbocker and hearing the conversations he had with the gentlemen who occupy - or have recently occupied - the main chairs in the Chancelleries on Mr. Knickerbocker's beat.

This roving reporter buttonholed more of Europe's mèn of destiny, but the answers got no more satisfactory. Curiously enough, they all seemed to agree that the next war "will end Europe as we know it." That idea is held everywhere. And a gloomier one is spreading: "That disarmament is impossible, that limitation of armaments is improbable and that armament upward is imperative for all."

This reasoning, built out of interchangeable parts of logic that are ready at hand for any one who wants to pick them up and put them together, is the sort that belongs in the day-to-day historical record of a daily paper's columns. Still, it has all the fascination of the jigsaw puzzles all New York was playing with last year when you can get so many parts gathered into a book. And Mr. Knickerbocker has a fine talent for collecting them. It's a well-conducted tour, pausing for inspection at all the main danger points, and one meets celebrities at every stop. What they say for publication may not be very near what they actually think, of course. Mr. Knickerbocker realizes that.

(2) John Gunther, A Fragment of Autobiography (1961) page 9

I contrived (April 1935) to visit Paris, Rome, Berlin, and Moscow in those three weeks. Meanwhile colleagues helped me, Knickerbocker most of all. He knew more about Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini than any other newspaperman in Europe, and on three successive long afternoons in London he valiantly, brilliantly emptied himself of these subjects for my benefit.

(3) Claude Bowers to Cordell Hull (12th April, 1937)

General Franco is becoming more and more intolerant towards war correspondents with his armies. He turned them all away when the attack on Malaga began. The men he then turned away had been with him for months and had written the most pronounced pro-Franco articles. No war correspondent with him could have been more satisfactory to him than Knickerbocker who was convinced of his early and inevitable victory when I saw him frequently five months ago. He returned to America three months ago and has now been ordered back. I have seen him twice in Saint-Jean-de-Luz at my home. He was waiting for a permit to cross the border and to rejoin the army. He has just been informed that he `cannot continue his journey to Spain'. I can only interpret this denial to mean that there must be something in the present situation that General Franco does not care to have blazoned to the world. I find Knickerbocker completely flabbergasted by the changed situation.

(4) Gonzalo de Aguilera Munro, interviewed by Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker for the Washington Post (10th May, 1937)

It is a race war, not merely a class war. You don't understand because you don't realize that there are two races in Spain - a slave race and a ruler race. Those reds, from President Azaña to the anarchists, are all slaves. It is our duty to put them back into their places - yes, put chains on them again, if you like. Modern sewer systems caused this war. Certainly because unimpeded natural selection would have killed off most of the 'red' vermin. The example of Azaña is a typical case. He might have been carried off by infantile paralysis, but he was saved from it by these cursed sewers. We've got to do away with sewers.... What you can't grasp is that any stupid Democrats, so called, lend themselves blindly to the ends of "red" revolution. All you Democrats are just handmaidens of bolshevism. Hitler is the only one who knows a "red" when he sees one... We must destroy this spawn of "red" schools which the so-called republic installed to teach the slaves to revolt. It is sufficient for the masses to know just enough reading to understand orders... We must restore the authority of the Church. Slaves need it to teach them to behave... It is damnable that women should vote. Nobody should vote - least of all women.

(5) Raymond Gram Swing, Good Evening (1964)

I want now to turn back to 1938 and the Munich crisis. I was on vacation and in Europe when it came to a head, so that I did not handle its development in my broadcasts. But I knew the gravity of what was happening and turned up in Prague on the very day that Czechoslovakia mobilized as a protest against the surrender of the Sudetenland to Nazi Germany. There I encountered colleagues hard at work, among then, some of my good friends, such as H. R. Knickerbocker, M. W. Fodor, John Whitaker, and Vincent Sheean. They were in constant touch with the Czech Foreign Office; they all knew President Eduard Benes well, and Ambassador Jan Masaryk in London even better. They understood fully the infamy of the Munich agreement and its evil portent for the future of Europe.

On the evening of my arrival, my colleagues and I occupied a large hotel room with a balcony overlooking Wenceslaus Square in the heart of the city. Hundreds of young men already were marching and shouting in the square. Knickerbocker explained to me the position. Benes had given in to the French and British on the Sudetenland issue, but his ministers had rejected the decision, as he foresaw, until it could be ratified by parliament. Benes then told the French and British that he was powerless and could not keep his promise. There-upon, the French and British told him that if he did not, Czechoslovakia would be branded as the "guilty" party in any trouble to follow, and France's treaty to defend Czechoslovakia against aggression would not go into operation. Benes thereupon called in his ministers again, and they bowed to the decree from Paris. Knickerbocker said that Czechoslovakia would have to fight, not only for itself, but for all of us and our children. Apparently, Benes had intended to delay acceptance so as to force Hitler to attack his country. Then both France and the Soviet Union would be required to defend Czechoslovakia by their treaties with that country. But he had not succeeded.

(6) Time Magazine (25th March, 1940)

Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker came from Yoakum, Tex. The son of a Methodist minister, he studied at minuscule Southwestern University, spent a few months in the army as a telegraph operator on the Mexican border, went north in 1919 to study medicine at Columbia. But all he could afford was a course in journalism, so he took that.

In 1923, still hoping to become a doctor, Knickerbocker went to Germany, matriculated at the University of Munich. To pay his way, he took a job as occasional correspondent for United Press. He was in Munich when Adolf Hitler set forth with a handful of followers from the Bürger-bräukeller (where last November's bomb exploded) on his first unsuccessful Putsch to seize the Government.

For ten years H. R. Knickerbocker covered Central Europe. For a series of 24 articles on The Red Trade Menace, in the Philadelphia Public Ledger, he won a Pulitzer Prize. Edged out of Germany after Hitler came to power, Knickerbocker colorfully reported wars in Ethiopia, Spain and China for Hearst's International News Service, saw German troops march into Austria, then into Czecho-Slovakia.

Later, after one month on the Allied front, covering World War II, he got a new urge, took leave of absence from I. N. S., flew back to the U. S. by Atlantic Clipper to lecture on Europe.

Said he, at his 71st lecture in Minneapolis last week: "If one were an international bookmaker, he would be busy now changing the odds in favor of Germany and Russia against the British and French. Until the Finnish peace, odds were 55-to-45 for an ultimate Allied victory. Now they are reversed."

The urge which drives slight, bespectacled lecturer Knickerbocker, with his shock of wavy, flame-red hair (balding on top), is his belief that this is very much a U. S. war. He makes no secret of his Franco-British sympathies, believes the war may last six years or longer, end in a Soviet Europe. In his first lectures he called for outright U. S. intervention. Now he no longer flatly advocates intervention in his lecture; but in the question period that follows, he generally makes his conviction amply clear. So far he has told an estimated 70,000 people his belief that:

1) The Treaty of Versailles was too lenient, not too hard.

2) If Hitler wins, the U. S. will be not much better off than Czecho-Slovakia was in 1938, will have to face the combined fleets of Germany, Italy, Russia, Japan, England, France.

3) The U. S. should throw its whole weight behind the Allies, send no troops, but arms and money, an air force, the U. S. Navy.

With 17 more speaking dates before his tour ends next month, with Finland defeated, last week Knickerbocker's voice took a more urgent tone as he talked with isolation-loving students at the University of Minnesota. Said he: "Why all this talk about not being emotional? What did God give us emotions for? To protect us from fear, of course."

(7) The New York Times (July 14, 1949)

BOMBAY, India, July 13-A simple private funeral service was held here this afternoon for five of the thirteen United States newspaper, magazine and radio correspondents who were killed in the crash of the Dutch KLM Constellation near Bombay yesterday. Public memorial rites for the entire group of twenty-one other passengers and the eleven crew members are scheduled for tomorrow at 12:30 P. M. at Bombay City Hall.

The bodies of Bertram D. Hulen of The New York Times, William Newton of the Scripps-Howard Newspaper Alliance, James Branyan of The Houston Post, Nat A. Barrows of The Chicago Daily News and Miss Elsie Dick of the Mutual Broadcasting System, for whom today's services were held in the Municipal Hospital, were cremated this evening. H. R. Knickerbocker of the broadcasting station WOR and Fred Colvig of The Denver Post are to be buried tomorrow.

The Consulate General is awaiting word from Washington as to relatives' wishes regarding the others. The United States Ambassador, Loy W. Henderson, flew from New Delhi early today with Lieut. Col. Robert Halloran, air attaché; Lieut. Commdr. George Kittredge, assistant naval attaché, and three American correspondents stationed in New Delhi, to attend the rites.

(8) Edgar P. Sneed, Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker: Handbook of Texas (1st February, 1995)

Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker, writer, was born in Yoakum, Texas, on January 31, 1898, the son of Rev. Hubert Delancey and Julia Catherine (Opdenweyer) Knickerbocker. After graduation from Southwestern University in 1917 he served briefly with the United States Army on the Mexican border and then delivered milk in Austin. In 1919 he went to Columbia University to study psychiatry. His career in journalism began in 1920, when he became a reporter for the Newark, New Jersey, Morning Ledger; in 1922 he reported for the New York Evening Post and the New York Sun, then returned to Texas as journalism department chairman at Southern Methodist University for the 1922–23 term. He went to Munich, Germany, with the intention of studying psychiatry, but historic events and his reporter's instinct intervened. He was a witness to the Beer Hall Putsch of Adolph Hitler on November 8–9, 1923. Shortly afterward he became assistant Berlin correspondent for the New York Evening Post and the Philadelphia Public Ledger. He became chief Berlin correspondent for these two newspapers in 1928 and continued in that capacity until 1941. His friends told the story that he secured his promotion by introducing his predecessor, Dorothy Thompson, to Sinclair Lewis and by promoting their subsequent romance and marriage. From 1925 to 1941 Knickerbocker was also a European correspondent for International News Service.

From 1923 to 1933 he based his activities in Berlin. Only from 1925 to 1927 did he divide his time between Berlin and Moscow, where he reported for INS. In Germany he published six books in German and wrote columns in two major German newspapers, the Vossische Zeitung and the Berliner Tageblatt. He circulated in highest German political, social, and cultural circles. His critical views on Soviet economy and foreign affairs were generally well received in Germany, especially his Der rote Handel lockt (1931), which was published in English as The Red Trade Menace (1931). In 1931 Knickerbocker won the Pulitzer Prize for his articles describing and analyzing the Soviet Five-Year Plan. His strong opposition to Hitler and the Nazi movement, however, made his position difficult when Hitler became a major political figure in 1932. With the Nazi takeover in 1933, Knickerbocker was deported and forced to report on Germany from beyond the frontiers of the Third Reich.

In 1933 he made an extensive research tour of Europe, on which he interviewed hundreds of public figures and many heads of state, asking the question beginning to trouble most Europeans and some Americans: "Will war come to Europe?" In his book Will War Come to Europe? (1934) he forecast a general European war. He spent the rest of his life witnessing, reporting, and interpreting the events foreshadowing the World War II. He covered the Italo-Abyssinian War in 1935–36, the Spanish Civil War in 1936–37, the early phases of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Anschluss and the Czech crisis in 1938, the defeat of France in 1940, and the battle of Britain in 1940.

In March and April 1940 Knickerbocker devoted himself to the American lecture circuit, strongly urging American support of the war against the Axis powers. Repeatedly in late 1940 and in 1941 he toured the United States declaring that "we should go into war today." On April 24, 1941, he spoke on the University of Texas campus, and on November 20, 1941, after a speech at Southern Methodist University, he exchanged heated remarks with students who opposed United States entry into the war. Knickerbocker summed up his views in the book Is Tomorrow Hitler's? (1941).

In 1941 he went to work for the Chicago Sun as its chief foreign correspondent in the Far East and South Pacific. In 1942 he followed Allied troops into North Africa, reporting for the Sun and acting as the official correspondent for the First Division of the United States Army. During the remainder of the war he reported from the European theater of military operations.

After the war Knickerbocker went to work for radio station WOR, Newark, New Jersey. He was on assignment with a team of journalists touring Southeast Asia when they were all killed in a plane crash near Bombay, India, on July 12, 1949. Knickerbocker was married first to Laura Patrick in 1918, and they had one son; his second marriage was to Agnes Schjoldager, and they had three daughters.