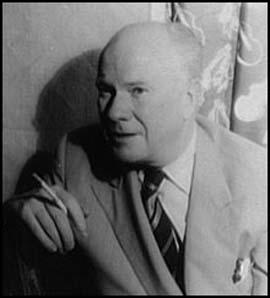

Vincent Sheean

Vincent Sheean, the son of William Sheean and Susan MacDerrnot, was born in Pana, Illinois on 5th December 1899. At the age of seventeen he enrolled at the University of Chicago. He later recalled: "The University of Chicago, one of the largest and richest institutions of learning in the world, was partly inhabited by a couple of thousand young nincompoops whose ambition in life was to get into the right fraternity or club, go to the right parties, and get elected to something or other."

In 1918 he joined the US Army with the intention of taking part in the First World War. He later wrote: "I was sorry when the war ended. I fumed with disappointment on the night of the false armistice - the celebrated night when the American newspapers reported the end of the war some days before it happened. We were all patriots then. We knew nothing about that horror and degradation which our elders who had been through the war were to put before us so unremittingly for the next fifteen years. There were millions of us, young Americans between the ages of fifteen or sixteen and eighteen or nineteen, who cursed freely all through the middle weeks of November. We felt cheated. We had been put into uniform with the definite promise that we were to be trained as officers and sent to France."

He returned to the University of Chicago in March 1919 but after the death of his mother in 1920 he moved to New York City and began work for the Daily News. He lived in Greenwich Village where he associated with left-wing figures such as Louise Bryant and Albert Rhys Williams who had reported on the Russian Revolution. In his autobiography he talked about listening "to talk about Lenin and Trotsky, got drunk in small bars with men from my newspaper and other newspapers... I had an immense amount of innocence to lose, and with the best will in the world I could not lose it quickly enough."

In 1922 he visited Europe. He eventually settled in Paris where he became foreign correspondent for The Chicago Tribune. During this period he became close friends with Ernest Hemingway and John Gunther. He also met many of Europe's political leaders. The first person he interviewed was Raymond Poincare and he was not impressed: "Poincare was not only the first politician I ever observed at close range; he was also the least imposing, the least suited to his historic role. He had no charm of any sort, no ease of manner, little dignity; his substitute for it was a sort of stiff-necked provincial didacticism... I never heard him make a generous statement in political matters and did not believe he was capable of such a thing. From hearing and seeing him repeatedly throughout the momentous two years I reached the conclusion that he hated the Germans as a Jersey farmer hates a rattlesnake."

Sheean reported on the League of Nations. As he pointed out: "The great hope in that order of ideas was the League of Nations. But the League fell into a palsy, terrified by Italy's threat to resign if anything serious was done. The French and British then took the problem out of the League's hands altogether and gave it to the Conference of Ambassadors in Paris. The Conference consisted of the ambassadors of the great allied powers of 1914-18, and had been invented to succeed the Supreme Council of Versailles." Sheean later quoted the words of Robert Cecil: "We can't always have what we want in this life. Very often we must be satisfied with what we can get."

Sheean went to Morocco to interview the popular rebel Abd el-Krim. He later wrote: "He personified his people in the best of their qualities, expressed and defined them, more than it is possible for any one man to do in more complicated societies. His genius was his people's raised to a higher power. In spite of his considerable acquaintance with the culture and ideas of Europe, he never for one moment saw the world or his particular problems in it from the point of view of a European... The singleness of Abd el-Krim's purpose was not, in the hills and valleys of his own people at that particular moment in their history, a proof of limitation; it was a proof of greatness. He can never have appeared a more heroic figure than he did to me during those days. Against his quality, the best of the pettifogging politicians of Europe looked like so many puppets." The time he spent with Abd el-Krim resulted in the writing of Sheean’s first book, An American Among the Riffi (1926).

In 1927 Vincent Sheean toured China where he met T. V. Soong and his sister, Soong Ching-ling, the wife of Sun Yatsen. Sheean was impressed with Soong: "He (T.V. Soong) was a young man of about my own age, trained at Harvard, intelligent, competent and honest, and had been Minister of Finance for the Cantonese government. The same post had been assigned to him at Hankow and also at Nanking, but at the precise moment of my arrival he had resigned it."

Sheean also interviewed Chiang Kai-shek: "I was summoned to see the general, Chiang Kai-shek. "This remarkable young man, who was then about thirty and looked less, had been born a poor Cantonese and was, to begin with, a common soldier. He was without education even in Chinese, and spoke only the dialect of his native city. He had been singled out for advancement by Sun Yat-sen, and showed enough ability to be pushed ahead through all ranks until he became, in 1927, commander-in-chief of the armies and, so far as the public was concerned, the military hero of the Revolution."

While in Hankow he met Rayna Prohme, a member of the American Communist Party. A mutual friend had described her as a "red-headed gal... who spit fire, mad as a hatter, a complete Bolshevik." Sheean was immediately taken by her: "She was slight, not very tall, with short red-gold hair and a frivolous turned-up nose. Her eyes... could actually change colour with the changes of light, or even with changes of mood. Her voice, fresh, cool and very American, sounded as if it had secret rivulets of laughter running underneath it all the time, ready to come to the surface without warning... I had never heard anybody laugh as she did - it was the gayest, most unself-conscious sound in the world. You might have thought that it did not come from a person at all, but from some impulse of gaiety in the air."

Rayna and Sheean went to Moscow together. Rayna wanted to study at the Lenin Institute "to be trained as a revolutionary instrument". Sheean was against the idea arguing that Marxism was "a false cloud". According to Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990): "They took rooms together, arguing late into the night about her decision. But she found the debates tiring, and often had trouble getting out of bed the following morning."

While on a visit to the apartment of Dorothy Thompson, another journalist based in the Soviet Union, Rayna fainted. She soon became extremely ill and Sheean's friend, Walter Duranty, arranged for her to be seen by a local doctor. Rayna told Sheean: "The doctor thinks I am losing my mind and that is the worst thing of all. He won't say so, but that is what he thinks. I can tell by the way he holds matches in front of my eyes and tests my responses. He doesn't think I can focus on anything."

Sheean recalled in his autobiography: "She had spoken vaguely of the fear before, and all I could do was say that I did not believe it was well founded. But on the next day she felt certain that this was the case, and it kept her silent and almost afraid to speak, even to me. I sat beside her hour after hour in the dark, silent room, and blackness pressed down and in upon us." Sheean said that two or three times she raised her voice to say: "Don't tell anybody". Rayna Prohme died of encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain, on Monday, 21st November 1927.

Sheean began writing Personal History in 1933. The book that tells the story of Sheean's experiences of reporting on the rise of fascism in Europe was published in 1935. Later that year he married Diana Forbes-Robertson, daughter of the English actor Johnston Forbes-Robertson. She was also a journalist and they often worked together on assignments. Sheean later admitted that he was not the best of husbands. "A good many newspapermen of the time and place could have been said to be without private lives or to treat their private lives with indifference - to marry and beget absent-mindedly, see their wives sometimes once a week, and live, in all the keener hours of their existence, in the office."

During the Spanish Civil War Vincent Sheean reported the conflict for New York Herald Tribune. He worked with a group of journalists that included Ernest Hemingway, William Forrest, Robert Capa, and Herbert Matthews. According to Paul Preston, the author of We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War: "Herbert Matthews, Robert Capa and Willie Forrest were among the last correspondents to leave Catalonia before the Francoists reached the French frontier. Sheean, Matthews, Buckley and Hemingway had been involved in a hair-raising crossing of the Ebro in a boat which was nearly smashed against some spikes."

Sheean was highly critical of the Non-Intervention policy of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain. In his book, Not Peace but the Sword (1939) he wrote about Chamberlain: "This strange, tardy awakening on the part of the Prime Minister was of no worth in the scales of history, and will do little to blind even his contemporaries to the true value of a man who has consistently put the interests of his own class and type above those of either his own nation or of humanity itself." Sheean once told an interviewer that his reputation for being in the midst of the news arose because of his “ardent sympathy for the downtrodden.”

At the beginning of the Second World War Sheean was based in London and covered the Blitz for the Saturday Evening Post. He was identified as being sympathetic to United States becoming involved in the war. Ernest Cuneo, who worked for British Security Coordination made contact with Sheean. Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that he was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Sheean, Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Dorothy Thompson, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Eric Sevareid, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Ralph Ingersoll, and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America".

Sheean's book, Personal History, was republished in 1940. In the new introduction Sheean admitted that a "formidable accretion to the power of Fascism as an ideological challenge had been made by Hitler's regime in Germany after 1933." The book was purchased by film producer Walter Wanger, and the section on the dangers of Nazi Germany became the basis for the production Foreign Correspondent that was directed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1940. Writers employed to work on the screenplay included Harold Clurman, Ben Hecht, John Howard Lawson and Budd Schulberg. It was changed to the fictional story of Johnny Jones, played by Joel McCrea, a American crime reporter reassigned as a foreign correspondent in London. He meets Stephen Fisher (Herbert Marshall), the head of the Universal Peace Party. It is not long before Jones gets entangled in international intrigue involving the kidnapping of Van Meer played by Albert Bassermann, who in real life was a refugee from Nazi Germany.

During the Second World War Sheean wrote his first novel, Bird of the Wilderness. He also spent time in India and China reporting on the war for the New York Herald Tribune. In 1946 he published This House Against This House. The following year he was in India and witnessed the assassination of Gandhi.

Sheean was a close friend of Edna St. Vincent Millay and her husband Eugen Boissevain. Edna was found dead at the bottom of the stairs on 19th October 1950. The following year Sheean published a tribute to her, Indigo Bunting: Memoir of Edna St.Vincent Millay.

In 1963 Sheean published Dorothy and Red, a book about the marriage of his friends Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis who he had known when they lived in Vermont: "The Lewises had bought a farm in Vermont, with two beautiful old houses on it. They owned the whole mountain, led a sylvan life there, and were always ready to take me in when I got to the point of incapacity to endure New York another minute.... We used to lead the simple life there, all three working away at something or other and meeting only at meal-times."

Vincent Sheean died of lung cancer on 16th March 1975 in Leggiuno, Italy.

Primary Sources

(1) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The Armistice came when I was eighteen. What it meant to the war generation I can only imagine from the stories they tell; to me it meant that we in the University of Chicago, that mountain range of twentieth-century Gothic near the shores of Lake Michigan, went out of uniform and into civilian clothes.

The world has changed so much that it seems downright indecent to tell the truth: I was sorry when the war ended. I fumed with disappointment on the night of the false armistice - the celebrated night when the American newspapers reported the end of the war some days before it happened. We were all patriots then. We knew nothing about that horror and degradation which our elders who had been through the war were to put before us so unremittingly for the next fifteen years. There were millions of us, young Americans between the ages of fifteen or sixteen and eighteen or nineteen, who cursed freely all through the middle weeks of November. We felt cheated. We had been put into uniform with the definite promise that we were to be trained as officers and sent to France. In my case, as in many others, this meant growing up in a hurry, sharing the terrors and excitements of a life so various, free and exalted that it was worth even such hardships as studying trigonometry. So we went into uniform and marched about the place from class to class like students in a military academy ; listened to learned professors lecturing about something called "War Aims"; lived in "barracks"; did rifle drill. The rifles were dummies, and the "barracks" were only the old dormitories rechristened, but such details made little difference.

(2) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The University of Chicago, one of the largest and richest institutions of learning in the world, was partly inhabited by a couple of thousand young nincompoops whose ambition in life was to get into the right fraternity or club, go to the right parties, and get elected to something or other. The frivolous two thousand -the undergraduate body, the 'campus '-may have been a minority, for the University contained a great many solitary workers in both the undergraduate and graduate fields ; but the minority thought itself a majority, thought itself, in fact, the whole of the University. And it was to the frivolous two thousand that I belonged.

(3) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

Raymond Poincare was not only the first politician I ever observed at close range ; he was also the least imposing, the least suited to his historic role. He had no charm of any sort, no ease of manner, little dignity ; his substitute for it was a sort of stiff-necked provincial didacticism. Compared to any other political leader of the same rank known to me afterwards - Briand, MacDonald, Stresemann, Mussolini - he seemed harsh, little-minded and inhuman. I never heard him make a generous statement in political matters and did not believe he was capable of such a thing. From hearing and seeing him repeatedly throughout the momentous two years I reached the conclusion that he hated the Germans as a Jersey farmer hates a rattlesnake. In his sharp, piggish eyes and his piercing voice there came a suggestion of terror and loathing whenever he had occasion to use the words Allemagne and Allemand. He was obliged to defend his policy frequently in the Chamber, and he always seemed to me, when the Germans were in question, to be near hysteria. His voice would rise to a shriek, he would shake documents aloft in his fist, and his admirers on the right would break into loud applause. On other subjects he was exact and dictatorial. He came from Lorraine ; the war had cost him dear; and he was unable to take a large view of any situation involving the Germans. He used to go about on Sundays dedicating soldiers' monuments in various villages, and in those melancholy hamlets, where sometimes every able-bodied man had been killed in the war, he did his best to keep the war hatreds alive. These speeches (which the Germans called Dorfprediger, village sermons) came nearly every Sunday; for months it was my duty to translate them and send them off to America ; and I always considered the money spent in cabling them to be a sad loss. One model speech, sent over by mail, would have done for them all. I felt that I could have written Poincare's village sermons, the "au fur et a mesure" speeches, blindfolded. He never varied his ideas, seldom his expressions ; for his whole term in 1922-24 he went on stubbornly verbigerating in the face of history. But, like anybody who resists the irresistible, he was swept away, and when he came back to power for the last time two years later the structure of "sanctions" and "gages", the old reparations schedules, the impossible system. he had attempted so fanatically to enforce, had gone for ever.

(4) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The death of Sarah Bernhardt led to my only glimpse of Poincare's enemy Clemenceau. Bernhardt died in the spring of 1923, giving the Parisian press and public a welcome opportunity for the display of funebrious sentiment, with street parades and tooting of trumpets, black ostrich feathers and noisy weeping. I was so carried away by the movement and trappings of grief that I wrote a rare piece of maudlin for my newspaper about the vanished divinity, and my employer, remarking that "This oughta bring tears from a turnip", ordered me to sign my name to it. My name was expressed in initials : J. V. Initials, it seemed, were no good for a newspaper signature, and I was ordered to use the second name, Vincent. Thus, without an effort of will on my own part, I acquired a name like a mask and have worried along behind it ever since.

Clemenceau was Bernhardt's friend, and although he had been living in retirement for months and notoriously disliked saying anything to the press, I was sent out to his house in the Rue Franklin to see him. I arrived just as M. le President was sitting down to his early dinner. After ten or fifteen minutes, during which I waited in a stuffy little salon and looked at the furniture, the door of the cubicle opened and an old man in a skull-cap catapulted in.

The effect given was that of immense energy-an effect for which he had doubtless worked many years, and achieved as the result of unwearied performance in the same role. He moved with a combination of bounce and drive that brought one automatically to attention. His eyes were beady, his whole expression concentrated and wary, as if both body and mind were held ever ready to spring. His skin was a deep yellow in colour, and in his silk skull-cap and black velvet jacket he looked like a particularly active old Chinaman. His brisk voice was business-like, slightly impatient, but not at all unfriendly. In his hand he carried his napkin, so as to remind me that he had left his dinner between dishes.

"Well, well, young man," he said (in English), "what can I do for you ? You know perfectly well that I don't give interviews."

"I've been sent to ask you for some expression about the death of Mme Sarah Bernhardt," I said.

"Anything you want to say, Mr President, is of interest in America."

"You think so, do you?" His yellow face was twisted in a grimace that might have passed for a smile.

"Well, what can I say about Mme Sarah Bernhardt? She was my old friend; I liked and admired her; she is dead; I'm sorry. I dined at her house ten days ago. Is that what you want to know?"

His English was excellent, clipped and briskly easy; but it was not to make this discovery that I had interrupted his dinner. I tried to get him to speak more fully about Mme Sarah Bernhardt and he did emit a few sentences of a commonplace order. But it was clear that the old man regarded the whole thing as a stupid invasion of his privacy, an dnerie typical of American journalism. He was right, of course. When he had yielded as much as he thought necessary to satisfy the curiosity of his American admirers he bounced over to me, shook hands, wished me luck and returned to his dinner. The whole episode had taken about ten minutes in all, but it was enough to make Clemenceau a more vivid figure in my mind than many of the politicians I was to see so often thereafter. His faults were no doubt without number, but he was at any rate a man who knew his own mind and talked in comprehensible language. It was impossible not to wonder how men like Poincare reached positions of great importance in the affairs of state, but no such speculation could arise in the youngest mind about Clemenceau. He must have been born to exercise power as a bird is born to fly or a fish to swim.

(5) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The great hope in that order of ideas was the League of Nations. But the League fell into a palsy, terrified by Italy's threat to resign if anything serious was done. The French and British then took the problem out of the League's hands altogether and gave it to the Conference of Ambassadors in Paris. The Conference consisted of the ambassadors of the great allied powers of 1914-18, and had been invented to succeed the Supreme Council of Versailles.

Their excellencies met in secret, negotiated in the turpitudinous but effective style known since diplomacy began, and eventually - by a combination of bribing, coaxing and cudgelling - got the Italians out of Corfu. Mussolini, of course, was able to say that he had always intended to evacuate the island when his terms were met; the Greeks did not dare say anything; the powers had at least kept the Adriatic open. On my first visit to Geneva I was to witness the meek acceptance of the ambassadorial decisions by the League Assembly.

(6) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

I attended the League Assembly of 1923 only in its dying hours. Of the depressing congress I was to remember best two episodes: a speech by the representative of the empire of Ethiopia, and a speech by Lord Robert Cecil.

Ethiopia had just been admitted to the League on a promise that it would make efforts to consider the abolition of slavery. The representative of the empire of Ethiopia (Abyssinia) was a decorative bit of business. He wore the blue and white skirts of his country, spoke in a language nobody present understood, and was rewarded with applause. All the earnest nonsense of the League of Nations was crystallized in the episode. The gentleman spoke with fervour; his speech was afterwards pompously translated into French and English by persons who did not know a word of Abyssinian; and the whole thing occupied the parliament of mankind for about two hours. Meanwhile the most serious problem of war and peace then before the League - the question of Corfu - was being settled in the ornate drawing-rooms of the Quai d'Orsay by a handful of tired old gentlemen who scarcely knew where Abyssinia was. The boredom and futility of Geneva were a shock to anybody who believed, as I then still tried to believe, that it might be possible to settle national differences by governmental agreement.

Lord Robert Cecil spoke at the very end of the Assembly, when the report of the Council of Ambassadors had finally been made and sent to Geneva for adoption by the League. The Assembly had been waiting for weeks to get a chance to talk about Corfu. It had been a forbidden subject on the floor after the first week of crisis. Now, with the humiliating report of the ambassadors before them, those who believed in the League could only protest or give up altogether. Many protested. Mr Branting of Sweden - champion of lost causes - was one of those who spoke most eloquently against the methods and results of the Corfu settlement. But Lord Robert Cecil was the preux chevalier of Geneva. He had asserted the League's authority throughout the dispute, often in language that could scarcely have been approved by the Tory (Baldwin) government of which he was a member. He had been steadfast, a true believer, never faltering in his defence of the Covenant that Italy had so brutally violated. The question in everybody's mind was: can it be pieced together again at all? Will there be a time in the future when the Covenant can be taken seriously? Can any power in future regard the League with respect? What can Cecil say?

That he was himself sad and tired was easy enough to see. With his thin, stooped shoulders, his hooked nose and his weary, claw-like hands - that strikingly Jewish appearance which is said to be characteristic of the Cecils - he looked like a saintly rabbi, calming and solacing his people with words of resignation. One of his sentences was to come into my head again and again for years afterwards.

"We can't always have what we want in this life," he said. "Very often we must be satisfied with what we can get."

Lord Robert had always suggested something steadier and more austere than was to be found elsewhere among Cabinet ministers. The politicians who later cut a great figure at the League - Briand, MacDonald, Stresemann, Herriot - were what is called "practical men"; they had their vanities and their partisan purposes; the League was useful to all of them, enhanced their reputations and solidified their support at home. They belonged to the professionally pro-League parties, the parties of the Left. Lord Robert Cecil was a different pair of sleeves: he had nothing, personally, to make out of the League; the party to which he technically belonged, the Tories, had no affection for Geneva ; his own political career was near its end. Small wonder that his conduct had caused him to represent, at that time, a nobility of spirit otherwise lacking in high places. His acceptance of the Corfu bargain was more than a surrender: it was a demonstration of the impotence of idealism, however honest and brave, under the system of nationalist capitalist states. I thought of his words as the swan-song of bourgeois idealism, for ever dying, for ever striking its flag, for ever yielding sadly, regretfully, to "the necessities of the practical world". He said it clearly enough, the whole creed of his kind: "We can't always have what we want in this life. Very often we must be satisfied with what we can get."

(7) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

I had no special light on the Matteotti affair - no foreigner had, I believe-but it was my first straight taste of the Fascist temper and as such deserves a bow. The Socialist deputy Matteotti had been carried off and murdered by a gang of Fascists, the chief of whom was the notorious Dumini, who boasted of his nine murders and his friendship with the Duce. When the body of Matteotti was discovered and his murderers sent to Regina Coeli there was such indignation, in and out of Italy, as threatened the whole position of the Fascist government. It ended, as might have been expected, by the creation of new laws and a new system of justice, whereby the Fascist dictatorship assumed the form it afterwards attempted to grow into that of a "total" state consistent within itself, intolerant of dissent and constructed so as to expunge all opposition automatically the moment it appeared; a party despotism of uncertain economic basis, philosophically no more than a doubtful time-variant of Marxism, but given vigour and superficial coherency by the bold, rubbery egotism of its individual leader. Until the affair of Matteotti, Fascism had governed through the "free" institutions of democracy, with a free press, an elected Parliament, and the free operation of equal justice under the Code Napoleon - all, of course, subject to intimidation, tinged with a flavour of castor oil, but ostensibly, at any rate, a government by the will of the people. After Matteotti all this changed: the "total" state was invented and the non-Fascists put in the position of a population under tutelage. The value of the new system would obviously only be tested when its historically accidental element, that of the Duce's person, was removed. It would take years to see what force might be left, out of all this militarization of energy, when the directing genius ceased to exert itself.

(8) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The Assembly of the League of Nations in 1924 was my second and last. It was the year of the MacDonald-Herriot "protocol"; it was, in fact, the MacDonald-Herriot year all round. Those worthy gentlemen, shining examples of the social democracy of Europe, had made up their minds to correct all the errors of their predecessors without attacking any of the causes for those errors. The attempt was interesting to watch. Mr MacDonald, seduced and intoxicated by the footlights, was already beginning to play his "historic role"; even then there could be seen the beginnings of the astonishing personal vanity and intellectual confusion that were to make him, in later years, the delight of the camera men and the sorrow of philosophers. He had already begun to talk in sentences like "good will between nations, upon which the relations of countries depends, is in turn dependent upon their willingness to understand each other" - the kind of harmless, meaningless iteration that permitted a whole decade in Europe to prepare for war. M. Herriot, a less ornamental figure, was at once more practical and more humane; his words were equally high-flown and round-about, but on some few points of reality he attempted to obtain settlements with the illusion of permanence. Between them, as they came to power in the spring of 1924, these two men represented for a while the hope of Europe : it was somehow expected that they, and the body of worried opinion they represented, might settle the problems of reparations and disarmament and effectively remove the causes that so obviously must lead in time to another war.

The Herriot-MacDonald regime began with the London Conference, the Dawes Plan, the evacuation of the Ruhr; it proceeded, in the memorable Assembly of 1924 at Geneva, to attempt a comprehensive system of enforcement of the peace. This system was embodied in the so-called "protocol", upon which the nations debated for months, and which was never ratified.

The MacDonald-Herriot "protocol" came in the middle of the decade of wordiness, before everybody had quite lost faith in such devices. At the outset it seemed possible that the protocol might actually, by redefining the Covenant of the League, set up a peace system that could be maintained. It was hoped to fix what constituted "war"; which side was the "aggressor"; and what were the duties of the other powers, members of the League, in punishing the "aggressor". Mr MacDonald, who lived on an island and was not in much danger, opened proceedings in fine style-supplied the organ music that brought the nations into their deliberations at Geneva: his was the grand processional. M. Herriot, who lived in a country where the enemy was at spitting distance, attempted to get some specific points of guarantee put into the document which the nations tried to draw up.

(9) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

If I had had only my own wishes to consult I might have stayed on with Abd el-Krim almost indefinitely. He personified his people in the best of their qualities, expressed and defined them, more than it is possible for any one man to do in more complicated societies. His genius was his people's raised to a higher power. In spite of his considerable acquaintance with the culture and ideas of Europe, he never for one moment saw the world or his particular problems in it from the point of view of a European. He saw them as any Riffian might see them; his superiority consisted in the fact that he could see them more clearly, attack them with greater courage and a more masterful intelligence. His ruling ideas, his purposes in life, were very few; they might all have been reduced to one, the "absolute independence" of the Rif....

The singleness of Abd el-Krim's purpose was not, in the hills and valleys of his own people at that particular moment in their history, a proof of limitation; it was a proof of greatness. He can never have appeared a more heroic figure than he did to me during those days. Against his quality, the best of the pettifogging politicians of Europe looked like so many puppets. It would have refreshed my belief in the capacity of mankind to rise above itself - its ability to reach, on occasions however rare, the summits indicated as possible by so much of its own literature and tradition - if I had been permitted to stay on at Ajdir and contemplate the phenomenon for a little longer.

(10) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

I went, first, to see Mr. T. V. Soong. He was a young man of about my own age, trained at Harvard, intelligent, competent and honest, and had been Minister of Finance for the Cantonese government. The same post had been assigned to him at Hankow and also at Nanking, but at the precise moment of my arrival he had resigned it. He continued resigning it for years, only to take it up again, until he was to become a kind of permanent Minister of Finance in all the Kuomintang governments. His usefulness came not only from the confidence inspired by his known capacity and honesty, but from his relationship to the semi-divine figure of Sun Yat-sen; he was a brother of the great man's widow. When I arrived in Shanghai he was living in Sun Yat-sen's house in the French Concession, the house given the old hero by the city for a permanent refuge in his. turbulent career.

Mr. Soong - "T. V.", as he was always called-received me well, thanks to the Borah letter. He spent some time explaining to me the difficulties of his own position, a problem that always worried him a good deal. As I came to know T. V. rather better in the following months, I grew to regard him as the most typical Liberal I had ever known - honest, worried, puzzled, unable to make up his mind between the horrors of capitalist imperialism and the horrors of Communist revolution. If China had only been America his happiness would have been complete, for he could have pretended not to know about the horrors. But in China it was impossible to step out of doors without seeing evidence, on every hand, of the brutal and inhuman exploitation of human labour by both Chinese and foreigners. T. V. was too sensitive not to be moved by such spectacles. And yet he had an equally nervous dread of any genuine revolution ; crowds frightened him, labour agitation and strikes made him ill, and the idea that the rich might ever be despoiled filled him with alarm. During a demonstration in Hankow one day his motor-car was engulfed by a mob and one of its windows was broken. He was, of course, promptly rescued by his guards and removed to safety, but the experience had a permanent effect on him-gave him the nervous dislike for mass action that controlled most of his political career and threw him at last, in spite of the sincerity of his idealism, into the camp of the reactionaries. He was an amiable, cultivated and charming young man, but he had no fitness for an important role in a great revolution. On the whole, I believe he realized it perfectly, and was made more miserable by that fact than by any other.

(11) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

In Nanking I repaired to a Chinese inn with my interpreter and sent a note to headquarters with T. V. Soong's line of introduction. An hour or so later I was summoned to see the general, Chiang Kai-shek.

This remarkable young man, who was then about thirty and looked less, had been born a poor Cantonese and was, to begin with, a common soldier. He was without education even in Chinese, and spoke only the dialect of his native city. He had been singled out for advancement by Sun Yat-sen, and showed enough ability to be pushed ahead through all ranks until he became, in 1927, commander-in-chief of the armies and, so far as the public was concerned, the military hero of the Revolution. Having arrived at his present eminence in great part by the aid of the Russians, he had now decided -under the persuasion of the Shanghai bankers and the immense revenues of the maritime provinces-to break with them and establish himself as a war-lord, modern style, with all the slogans and propaganda of the Kuomintang to cover his personal aggrandizement and give it a patriotico-revolutionary colour.

Chiang seemed (rather to my surprise) sensitive and alert. He was at pains to explain that he intended to carry out the whole programme of Sun Yat-sen, the Three People's Principles and all the rest of it, but without falling into "excesses". I was unable to bring him to any clear statement of his disagreement with the Russians or the Left Wing, and his thin brown face worked anxiously as he talked round the subject, avoiding its pitfalls. I cursed the necessity for an interpreter - particularly one whose command of both languages was obviously so limited-and wished, not for the first time, that the Esperantists had been more successful in their efforts. But even through the clouds of misapprehension set up by my friend, the returned student from the United States, I could discern the eager, ambitious nature of Chiang Kai-shek's mind, his anxiety to be thought well of, his desire to give his personal ambitions the protective coloration of a revolutionary doctrine and vocabulary. The phrases adopted by all members of the Kuomintang, from Right to Left, were used by him over and over again: "wicked gentry" (i.e., reactionary landlords), "foreign imperialism" and "unequal treaties", the traditional enemies of the Cantonese movement. But upon the methods he intended to use to combat his enemies he was vague. It was impossible to avoid the conclusion that with this young man, in spite of his remarkable opportunities, the phrases of the movement had not sunk beyond the top layer of consciousness. He remained a shrewd, ambitious, energetic Cantonese with his way to make in the world, and I fully believed that he would make it. I thought I detected, about his mouth and eyes, one of the rarest of human expressions, the look of cruelty. It may, indeed, have been only the characteristic look of a nervous, short-tempered man, but in later weeks, when his counter-revolution reached its height and the Communists were being tortured and butchered at his command, I was to remember the flickering mouth and anxious eyes of Chiang Kai-shek.

(12) Vincent Sheean, Personal History (1935)

The Lewises had bought a farm in Vermont, with two beautiful old houses on it. They owned the whole mountain, led a sylvan life there, and were always ready to take me in when I got to the point of incapacity to endure New York another minute. With Dorothy and Red it was possible to rest, work, talk nonsense and have a good laugh. I think New York had much the same disruptive effect on them that it did on me, and when they were in Vermont they shut it out more successfully than anybody I knew. We used to lead the simple life there, all three working away at something or other and meeting only at meal-times. Red was writing Dodsworth when I first went there; he was revising the proofs of Ann Vickers the last time. His methods of work stunned me at first, and I used to wonder if writing a good book was actually as arduous as it seemed. It took me a long time to perceive that the marvellous architectural solidity of his novels, their incomparable vitality, depended upon his willingness to work at a book as if he were creating a world. To get a name for a character he would examine and reject thousands of names ; to get a street or a house right he would build it, actually construct it in cardboard ; to follow one of his characters from point to point in one of his imaginary cities he would make a map. He was the only writer I have ever known who knew exactly what every word meant before he used it. Whether it was classical English or the slang of the Middle West, he was sure of it before he put it down - and being sure of a word does not mean, of course, the mere ability to define it. Red knew where his words came from, what their associations were, how they were variously pronounced, and often just how they had been used throughout the history of the language. He had an infallible ear for words, as can be seen in the dialogue of such books as Babbitt ; he had an amazing memory, and he had read, I believe, every book ever written in or translated into English. His ruthlessness with his own work was a part of the phenomenon : he thought nothing of throwing away a hundred thousand words, cutting out more than he left in, or abandoning a novel altogether when it did not please him. The spectacle of such volcanic energy under the control of a first-rate artistic conscience was one of the most impressive that could have been offered a lazy youth, and it should have done me far more good than it did. I was not yet ready, however, for the disheartening fact that writing is and must always be hard work; I tried to imagine that Red's methods were suited only to himself, and that good books grew on bushes. As the truth afterwards became apparent, year after year, I was to think often of Red and his extraordinary organized effort, like that of an army in action along an extended front. He was, of course, a man of genius; but no amount of genius could have created the world of his rich, solid and various novels.

(13) Vincent Sheean, Not Peace but the Sword (1939)

Madrid, the mushroom, the parasite, created by a monarch's whim, an aristocracy's extravagance and the heartless ostentation of the new rich had found its soul in the pride and courage of its workers. They had turned the brothel and show window of feudal Spain into this epic. Whatever the future might determine in the struggle against fascist barbarism, Madrid had already done so much more than its share that its name would lie forever across the mind of man, sometimes in reproach, sometimes in rebuke, sometimes as a reflex of the heroic tension that is still not lost from our race on earth. In this one place, if nowhere else, the dignity of the common man has stood firm against the world.

(14) Vincent Sheean, Not Peace but the Sword (1939)

One time I went off to the front for three or four days by myself (rather against the advice of the local press attaché) and never had a moment's trouble. The boys who drove trucks of food or munitions were always ready to give me a lift; the military commanders were affable and informative; I could always find a place to sleep and a blanket to cover me.

(15) Vincent Sheean, Not Peace but the Sword (1939)

This strange, tardy awakening on the part of the Prime Minister was of no worth in the scales of history, and will do little to blind even his contemporaries to the true value of a man who has consistently put the interests of his own class and type above those of either his own nation or of humanity itself.