Albert Rhys Williams

Albert Rhys Williams, the son of David Williams, a Congregationalist minister and Esther Rhys, was born in Greenwich, Ohio, on 28th September, 1883. Both of his parents had been born in Wales before emigrating to the United States.

After graduating from high school in Hancock, Delaware County, in 1897, he worked in a lumber yard and a clothing store. In 1900 he entered Marietta College where he edited the college newspaper. He also joined the American Socialist Party and became involved in organizing trade unionists.

In 1904 he began attending the Hartford Theological Seminary. Williams also wrote a column for the Hartford Evening Post. In 1907 he moved to New York City where he worked at the Settlement House of the Spring Street Presbyterian Church. During this period he became close to Norman Thomas and the two men organized men's club debates. He also travelled to Britain where he met leaders of the Labour Party. In 1908 he campaigned for Eugene Debs in his failed presidential campaign.

Williams began associating with a group of socialists that met at the apartment of Mabel Dodge in the city. At Dodge's parties Williams met John Reed, Lincoln Steffens, Robert Edmond Jones, Margaret Sanger, Louise Bryant, Bill Haywood, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, Frances Perkins, Amos Pinchot, Frank Harris, Charles Demuth, Andrew Dasburg, George Sylvester Viereck, John Collier, Carl Van Vechten and Amy Lowell. As Bertram D. Wolfe explained: "Sometimes Mrs. Dodge set the subject and selected the opening speaker; sometimes she shifted the night to make sure that none would know of the gathering expect those she personally notified." Dodge pointed out in her autobiography, Intimate Memories: "I switched from the usual Wednesday to a Monday, so that none but more or less radical sympathizers would be there."

Williams became the minister of the Maverick Congregational Church in Boston. He continued to advocate socialism and during the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike, he raised money for those involved in the dispute. In 1914 Williams resigned his post and found work as a journalist with the magazine, Outlook. He was sent to Europe to cover the First World War. He was arrested in Belgium and briefly detained by Germans who suspected him of being a British spy.

He also worked closely with a group of photographers sent to cover the war: "There were a group of young war-photographers to whom danger was a magnet. Though none of them had yet reached the age of thirty, they had seen service in all the stirring events of Europe and even around the globe. Where the clouds lowered and the seas tossed, there they flocked. Like stormy petrels they rushed to the center of the swirling world. That was their element. A freelance, a representative of the Northcliffe press, and two movie-men comprised this little group and made an island of English amidst the general babel."

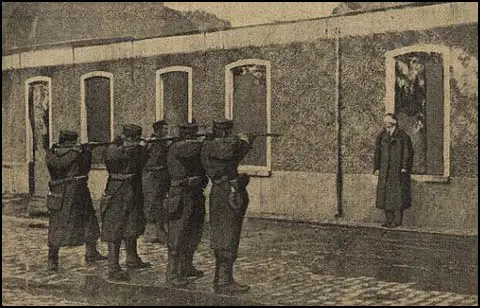

While he was in Belgium he was asked by a journalist: "Wouldn't you like to have a photograph of yourself in these war-surroundings, just to take home as a souvenir?" The idea appealed to him. After rejecting some commonplace suggestions, the journalist exclaimed: "I have it. Shot as a German Spy. There's the wall to stand up against; and we'll pick a crack firing-squad out of these Belgians."

Williams later recalled: "I acquiesced in the plan and was led over to the wall while a movie-man whipped out a handkerchief and tied it over my eyes. The director then took a firing squad in hand. He had but recently witnessed the execution of a spy where he had almost burst with a desire to photograph the scene. It had been excruciating torture to restrain himself. But the experience had made him feel conversant with the etiquette of shooting a spy, as it was being done amongst the very best firing-squads. He made it now stand him in good stead." A week later the photograph appeared in the Daily Mirror. It included the caption: "The Belgians have a short, sharp method of dealing with the Kaiser's rat-hole spies. This one was caught near Termonde and, after being blindfolded, the firing-squad soon put an end to his inglorious career."

On his return to the United States he published In the Claws of the German Eagle (1917). He decided after the success of the book to resign from the church and pursue a career as a journalist and writer. He joined the New York Post and was sent to Petrograd to report on the conflict that was taking place in that country following the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II.

On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. However, Kerensky, like his predecessor, George Lvov, was unwilling to end the war. In fact, soon after taking office, he announced a new summer offensive.

Soldiers on the Eastern Front were dismayed at the news and regiments began to refuse to move to the front line. There was a rapid increase in the number of men deserting and by the autumn of 1917 an estimated 2 million men had unofficially left the Russian Army. Williams reported: "In thousands the soldiers were throwing down their guns and streaming from the front. Like plagues of locusts they came, clogging railways, highways and waterways. They swarmed down on trains, packing roofs and platforms, clinging to car-steps like clusters of grapes, sometimes evicting passengers from their berths."

Williams got to know Vladimir Lenin. He later argued: "He was the most thoroughly civilized and humane man I ever have known, as nice a one as I ever knew, in addition to being a great man." Williams was convinced that the Bolsheviks would become the new rulers: "The Bolsheviks understood the people. They were strong among the more literate strata, like the sailors, and comprised largely the artisans and labourers of the cities. Sprung directly from the people's lions they spoke the people's language, shared their sorrows and thought their thoughts. They were the people. So they were trusted."

In July, Williams addressed the All-Russian Congress of Soviets: "I bring you greetings from the Socialists of America. We do not venture to tell you here how to run a Revolution. Rather we come here to learn its lesson and to express our appreciation for your great achievements. A dark cloud of despair and violence was hanging over mankind threatening to extinguish the torch of civilization in streams of blood. But you arose, comrades, and the torch flamed up anew. You have resurrected in all hearts everywhere a new faith in freedom. You have made the political revolution. Freed from the threat of German militarism your next task is the Social revolution. Then the workers of the world will no longer look to the West, but to the East - toward great Russia, to the Field of Mars in Petrograd, where lie the first martyrs of your revolution."

Lavr Kornilov responded by sending troops under the leadership of General Krymov to take control of Petrograd. Alexander Kerensky was now in danger and was forced to ask the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but Lenin made clear they would be fighting against Kornilov rather than for Kerensky. Within a few days the Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided not to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody.

Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin now urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks began to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace.

Williams was with John Reed and Louise Bryant, when they decided to head for the Winter Palace: "We had been sitting in Smolny, gripped by the pleas of the speakers, when out of the night that other voice crashed into the lighted hall - the cannon of the cruiser Aurora, firing at the Winter Palace. Steady, insistent, came the ominous beat of the cannon, breaking the spell of the speakers upon us. We could not resist its call and hurried away. Outside, a big motor-truck with engines throbbing was starting for the city. We climbed aboard and tore through the night, a plunging comet, flying a tail of white posters in our wake. As we come into the Palace Square the booming of the guns die away. The rifles no longer crackle through the dark. The Red Guards are crawling out to carry off the dead and dying."

The attacks on the Winter Palace caused little damage but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the building and arrested the Cabinet ministers. Williams reported: "A terrible lust lays hold of the mob - the lust that ravishing beauty incites in the long starved and long denied - the lust of loot. Even we, as spectators, are not immune to it. It burns up the last vestige of restraint and leaves one passion flaming in the veins - the passion to sack and pillage. Their eyes fall upon this treasure-trove, and their hands follow."

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Vladimir Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Felix Dzerzhinsky (Internal Affairs), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War).

Williams was critical about the violence that followed the Russian Revolution: "The Revolution was not everywhere powerful enough to check the savage passions of the mobs. Not always was it on time to allay the primitive blood-lusts. Unoffending citizens were assaulted by hooligans. In out-of-the-way places half-savages, calling themselves Red Guards, committed heinous crimes. At the front General Dukhonin was dragged from his carriage and torn to pieces despite the protesting commissars. Even in Petrograd some Yunkers were clubbed to death by the storming crowds; others were pitched into the Neva."

Vladimir Lenin demobilized the army and announced that he planned to seek an armistice with Germany. In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread to other countries.

After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers. The Brest-Litovsk Treaty resulted in the Russians surrendering the Ukraine, Finland, the Baltic provinces, the Caucasus and Poland.

The decision increased opposition to the Bolshevik government and General Lavr Kornilov now organized a Volunteer Army. Over the next few months other groups who opposed the Soviet regime joined the struggle. Eventually these soldiers who fought against the Red Army during the Civil War became known as the White Army.

Williams was appalled when President Woodrow Wilson sent troops in an attempt to defeat the Bolshevik government. "I never ceased to feel shame for the role my country played in this joint effort to strangle bolshevism in its cradle and socialism for good and all." Williams volunteered to join the Red Army but Vladimir Lenin rejected the offer and said he was more important to him in the field of propaganda. He later wrote. "If I helped in some small way to mitigate the guilt of being an American, I am satisfied."

Williams returned to America and based in San Francisco he toured the country making speeches attempting to explain the Russian Revolution. The New York Times wrote that "the greatest creation of Bolshevism is not Trotsky's army, but Albert Rhys Williams, and the singular audiences that applaud him." Williams, like John Reed and Louise Bryant, gave evidence before the United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee, but he was unable to modifying the subcommittee's anti-Communist opinions. In 1919 he published Lenin, the Man and His Work (1919).

Williams returned to Russia in 1922 and had articles published in the New Republic, the Atlantic Monthly, The Nation. His book Through the Russian Revolution was published in 1923. He wrote that he was unwilling to join the growing band of critics: "When I am tempted to join the wailers and the mud-slingers my mind goes back to the tremendous obstacles it confronted. In the first place the Soviet faced the same conditions that had overwhelmed the Tsar and Kerensky governments, i.e., the dislocation of industry, the paralysis of transport, the hunger and misery of the masses. In the second place the Soviet had to cope with a hundred new obstacles - desertion of the intelligentsia, strike of the old officials, sabotage of the technicians, excommunication by the church, the blockade by the Allies. It was cut off from the grain fields of the Ukraine, the oil fields of Baku, the coal mines of the Don, the cotton of Turkestan - fuel and food reserves were gone."

In 1923 he married Lucita Squier, who was making a film on famine relief for the Quakers. After they returned to the United States they settled in Carmel, California. He made several visits to the Soviet Union and was unhappy with the rule of Joseph Stalin. However, he told friends he was unwilling to "aid anti-Communist hysteria". According to Peter Hughes: "He (Williams) also believed that American and other foreign intervention during the period of the Russian Civil War led to the deaths of many promising idealistic Bolshevik leaders, leaving the reins of government to the few and the ruthless. He saw Stalinism as a temporary setback in a long train of history in which Communism would lead humankind to a better world."

During the Second World War he wrote The Russians: the Land, the People, and Why They Fight (1943) and promoted Russian War Relief. Williams never joined the American Communist Party but remained a socialist. He wrote: "If I have remained true to the Revolution and still look forward to the final triumph of socialism in the world, it is because, like Lenin, I do believe in the essential goodness of man."

Albert Rhys Williams died on 27th February, 1962. Journey into Revolution, which was edited and completed by his wife, was published in 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Rhys Williams, In the Claws of the German Eagle (1917)

There were a group of young war-photographers to whom danger was a magnet. Though none of them had yet reached the age of thirty, they had seen service in all the stirring events of Europe and even around the globe. Where the clouds lowered and the seas tossed, there they flocked. Like stormy petrels they rushed to the center of the swirling world. That was their element. A freelance, a representative of the Northcliffe press, and two movie-men comprised this little group and made an island of English amidst the general babel.

Like most men who have seen much of the world, they had ceased to be cynics. When I came to them out of the rain, carrying no other introduction than a dripping overcoat, they welcomed me into their company and whiled away the evening with tales of the Balkan wars. They were in high spirits over their exploits of the previous day, when the Germans, withdrawing from Melle on the outskirts of the city, had left a long row of cottages still burning. As the enemy troops pulled out the further end of the street, the movie men came in at the other and caught the pictures of the still blazing houses. We went down to view them on the screen. To the gentle throbbing of drums and piano, the citizens of Ghent viewed the unique spectacle of their own suburbs going up in smoke.

(2) Albert Rhys Williams, In the Claws of the German Eagle (1917)

While his little army rested from their manoeuvers the Director-in-Chief turned to me and said:

"Wouldn't you like to have a photograph of yourself in these war-surroundings, just to take home as a souvenir?"

That appealed to me. After rejecting some commonplace suggestions, he exclaimed: "I have it. Shot as a German Spy. There's the wall to stand up against; and we'll pick a crack firing-squad out of these Belgians. A little bit of all right, eh ?"

I acquiesced in the plan and was led over to the wall while a movie-man whipped out a handkerchief and tied it over my eyes. The director then took a firing squad in hand. He had but recently witnessed the execution of a spy where he had almost burst with a desire to photograph the scene. It had been excruciating torture to restrain himself. But the experience had made him feel conversant with the etiquette of shooting a spy, as it was being done amongst the very best firing-squads. He made it now stand him in good stead.

"Aim right across the bandage," the director coached them. I could hear one of the soldiers laughing excitedly as he was warming up to the rehearsal. It occurred to me that I was reposing a lot of confidence in a stray band of soldiers. Some one of those Belgians, gifted with a lively imagination, might get carried away with the suggestion and act as if I really were a German spy...

A week later I picked up the London Daily Mirror from a news-stand. I opened up the paper and what was my surprise to see a big spread picture of myself, lined up against that row of Melle cottages and being shot for the delectation of the British public. There is the same long raincoat that runs as a motif through all the other pictures. Underneath it were the words: "The Belgians have a short, sharp method of dealing with the Kaiser's rat-hole spies. This one was caught near Termonde and, after being blindfolded, the firing-squad soon put an end to his inglorious career."

One would not call it fame exactly, even though I played the star-role. But it is a source of some satisfaction to have helped a royal lot of fellows to a first-class scoop. As the "authentic spy-picture of the war," it has had a broadcast circulation. I have seen it in publications ranging all the way from The Police Gazette to Collier's Photographic History of the European War. In a university club I once chanced upon a group gathered around this identical picture. They were discussing the psychology of this "poor devil" in the moments before he was shot. It was a further source of satisfaction to step in and arbitrarily contradict all their conclusions and, having shown them how totally mistaken they were, proceed to tell them exactly how the victim felt. This high-handed manner nettled one fellow terribly.

(3) Albert Rhys Williams, speech to the All-Russian Congress of Soviets (8th July, 1917)

I bring you greetings from the Socialists of America. We do not venture to tell you here how to run a Revolution. Rather we come here to learn its lesson and to express our appreciation for your great achievements.

A dark cloud of despair and violence was hanging over mankind threatening to extinguish the torch of civilization in streams of blood. But you arose, comrades, and the torch flamed up anew. You have resurrected in all hearts everywhere a new faith in freedom.

You have made the political revolution. Freed from the threat of German militarism your next task is the Social revolution. Then the workers of the world will no longer look to the West, but to the East - toward great Russia, to the Field of Mars in Petrograd, where lie the first martyrs of your revolution.

(4) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

The Bolsheviks understood the people. They were strong among the more literate strata, like the sailors, and comprised largely the artisans and labourers of the cities. Sprung directly from the people's lions they spoke the people's language, shared their sorrows and thought their thoughts. They were the people. So they were trusted.

(5) Albert Rhys Williams described the arrival of troops to put down the Bolshevik uprising in July, 1917, in his book, Through the Russian Revolution.

On the third day the troops arrive. Bicycle battalions, the reserve regiments, and then the long grim lines of horsemen, the sun glancing on the tips of their lances. They are the Cossacks, ancient foes of the revolutionists, bring dread to the workers and the joy to the bourgeoisie. The avenues are filled now with well-dressed throngs cheering the Cossacks, crying "Shoot the rabble". "String up the Bolsheviks".

A wave of reaction runs through the city. Insurgent regiments are disarmed. The death penalty is restored. The Bolshevik papers are suppressed. Forged documents attesting the Bolsheviks as German agents are handled to the press. Leaders like Trotsky and Kollontai are thrown into prison. Lenin and Zinoviev are driven into hiding. In all quarters sudden seizures, assaults and murder of workingmen.

(4) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

In thousands the soldiers were throwing down their guns and streaming from the front. Like plagues of locusts they came, clogging railways, highways and waterways. They swarmed down on trains, packing roofs and platforms, clinging to car-steps like clusters of grapes, sometimes evicting passengers from their berths.

The ruling-class used every device to keep those weapons in the soldiers' hands. It waved the flag and screamed "Victory and Glory." It organized Women's Battalions of Death crying "Shame on you men to let girls do your fighting." It placed machine-guns in the rear of rebelling regiments declaring certain death to those who retreated.

(7) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

When the news of Kornilov's advance on Petrograd was flashed to Kronstadt and the Baltic Fleet, it aroused the sailors like a thunderbolt. From their ships and island citadel they came pouring out in tens of thousands and bivouacked on the Field of Mars. They stood guard at all the nerve centres of the city, the railways and the Winter Palace. With the big sailor Dybenko leading, they drove headlong into the midst of Kornilov's soldiers exhorting them not to advance.

(8) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

Attempt is made to suppress the Revolution by force of arms. Kerensky begins calling "dependable" troops into the city; that is, troops that may be depended upon to shoot down the rising workers. Among these are the Zenith Battery and the Cyclists' Battalion. Along the highroads on which these units are advancing into the city the Revolution posts its forces. They subject these troops to a withering fire of arguments and pleas. Result: these troops that are being rushed to the city to crush the Revolution enter instead to aid and abet it.

(9) Albert Rhys Williams was with Louise Bryant, Bessie Beatty and John Reed when the Winter Palace was taken on 7th November, 1917.

We had been sitting in Smolny, gripped by the pleas of the speakers, when out of the night that other voice crashed into the lighted hall - the cannon of the cruiser Aurora, firing at the Winter Palace. Steady, insistent, came the ominous beat of the cannon, breaking the spell of the speakers upon us. We could not resist its call and hurried away.

Outside, a big motor-truck with engines throbbing was starting for the city. We climbed aboard and tore through the night, a plunging comet, flying a tail of white posters in our wake. As we come into the Palace Square the booming of the guns die away. The rifles no longer crackle through the dark. The Red Guards are crawling out to carry off the dead and dying.

Forming a column, they pour through the Red Arch and creep forward, silent. Near the barricade they emerge into the light blazing from within the palace. They scale the rampart of logs, and storm through the iron gateway into the open doors of the east wing - the mob swarming in behind them.

A terrible lust lays hold of the mob - the lust that ravishing beauty incites in the long starved and long denied - the lust of loot. Even we, as spectators, are not immune to it. It burns up the last vestige of restraint and leaves one passion flaming in the veins - the passion to sack and pillage. Their eyes fall upon this treasure-trove, and their hands follow.

Along the walls of the vaulted chamber we enter there runs a row of huge packing-cases. With the butts of their rifles, the soldiers batter open the boxes, spilling out streams of curtains, linen, clocks, vases and plates.

Pandemonium breaks loose in the Palace. It rolls and echoes with myriad sounds. Tearing of cloth and wood, clatter of glass from splintered windows, clumping of heavy boots upon the parquet floor, the crashing of a thousand voices against the ceiling. Voices jubilant, then jangling over division of the spoils. Voices hoarse, high-pitched, muttering, cursing.

Then another voice breaks into this babel - the clear, compelling voice of the Revolution. It speaks through the tongues of its ardent votaries, the Petrograd workingmen. There is just a handful of them, weazened and undersized, but into the ranks of these big peasant soldiers they plunge, crying out - "Take nothing. The Revolution forbids it. No looting. This is the property of the people."

(10) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

The Revolution was not everywhere powerful enough to check the savage passions of the mobs. Not always was it on time to allay the primitive blood-lusts. Unoffending citizens were assaulted by hooligans. In out-of-the-way places half-savages, calling themselves Red Guards, committed heinous crimes. At the front General Dukhonin was dragged from his carriage and torn to pieces despite the protesting commissars. Even in Petrograd some Yunkers were clubbed to death by the storming crowds; others were pitched into the Neva.

(11) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

The Tsar had used the priests of the Greek Orthodox Church as his spiritual police making "Religion the opiate of the people." With threats of hell and promises of heaven the masses had been bludgeoned into submission to autocracy. Now the church was called to perform the same function for the bourgeoisie. By solemn proclamation the Bolsheviks were excommunicated from all its rites and services.

The Bolsheviks made no direct assault upon religion, but separated Church from State. The flow of government funds into the ecclesiastical coffers was stopped. Marriage was declared a civil institution. The monastic lands were confiscated. Parts of monasteries were turned into hospitals.

(12) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

For four years the Communists have had control of Russia. What are the fruits of their stewardship? "Repression, tyranny, violence," cry the enemies. "They have abolished free speech, free press, free assembly. They have imposed drastic military conscription and compulsory labour. They have been incompetent in government, inefficient in industry. They have subordinated the Soviets to the Communist Party. They have lowered their Communist ideals, changed and shifted their program and compromised with the capitalists."

Some of these charges are exaggerated. Many can be explained away. Friends of the Soviet grieve over them. Their enemies have summoned the world to shudder and protest against them.

When I am tempted to join the wailers and the mud-slingers my mind goes back to the tremendous obstacles it confronted. In the first place the Soviet faced the same conditions that had overwhelmed the Tsar and Kerensky governments, i.e., the dislocation of industry, the paralysis of transport, the hunger and misery of the masses.

In the second place the Soviet had to cope with a hundred new obstacles - desertion of the intelligentsia, strike of the old officials, sabotage of the technicians, excommunication by the church, the blockade by the Allies. It was cut off from the grain fields of the Ukraine, the oil fields of Baku, the coal mines of the Don, the cotton of Turkestan - fuel and food reserves were gone.

(13) Albert Rhys Williams, The Soviets (1937)

Give man the vision of a new world without poverty or oppression. Let him lose himself completely in the struggle to achieve it. Let him explore the universe, enriching himself and mankind with the wonders of science and the beauty of art. Let him understand that in humanity his noblest deeds and thoughts and aspirations go on forever. Thus may one find the true meaning of life, the fulfillment and satisfaction of his deepest desires.

© John Simkin, March 2013