History of California

It is believed that humans arrived in California from north-east Asia about 12,000 years ago. They divided and separated into groups that chose different areas to settle. This included the Chahuilla, Chumash, Costanoans, Gabrielino, Karok, Maidu, Miwok, Wintu and Yokut tribes. The anthropologist, Alfred L. Kroeber, has argued that large tribes were rare in California. He claimed that most lived in "tribelets" that contained up to 500 people.

Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has argued that by the 15th century "something approaching one third of all Native Americans living within the present day boundaries of the continental United States - which is to say, more than three hundred thousand people - are estimated to have been living within the present-day boundaries of California."

The Chumash lived along the Pacific Coast from San Luis Obispo to Malibu in the south and inland to the San Joaquin Valley. According to Evelyn Wolfson: "It is an area of long mountain ranges, broad valleys, freshwater rivers, and dry plains. Food resources were limitless and the Indians lived entirely off the land all year. On the hilly rugged offshore islands, strong winds and constant mild temperatures provided excellent fishing."

According to the authors of The Natural World of the California Indians (1980): "The Chumash were the most sea-oriented people of the state, a specialization made possible by their seagoing plank canoes, which were propelled by double-bladed paddles. The Chumash had colonized the offshore islands of Santa Barbara, San Miguel, Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa".

Jean-François de Galaup de la Pérouse was one of the first to record the behaviour of these tribes on the coast of California. He recalled meeting members of the Costanoans tribe while he was in Monterey: "These Indians are very skilful with the bow; they killed some tiny birds in our presence; it must be said that their patience as they creep towards them is hard to describe; they hide and, so to speak, snake up to the game, releasing the arrow from a mere 15 paces. Their skill with large game is even more impressive; we all of us saw an Indian with a deer's head tied over his own, crawling on all fours, pretending to eat grass, and carrying out this pantomime in such a way that our hunters would have shot him from 30 paces if they had not been forewarned. In this way they go up to deer herds within very close range and kill them with their arrows."

The Miwok passed down legends by word of mouth that explained the origin of several of the most beautiful features of the Yosemite Valley. They believed that El Capitan, was formed when two cub bears got separated from their mother. According to the story: "One hot day they slipped away from their mother and went down to the river for a swim. When they came out of the water, they were so tired that they lay down to rest on an immense, flat boulder, and fell fast asleep. While they slumbered, the huge rock began to slowly rise until at length it towered into the blue sky far above the tree-tops, and wooly, white clouds fell over the sleeping cubs like fleecy coverlets."

A large number of the Native American tribes harvested tobacco. It was smoked, mostly for soporific effects, in pipes of clay. Robert F. Heizer has argued: "Tobacco is remarkable because it was raised in a semi-horticulture: special plots were chosen, the brush was burned, seeds were planted in the ashes, and the plot was tended by thinning and weeding. Tobacco was grown in far Northern California, removed a great distance from the influences of agricultural peoples."

Stephen Powers argues in his book, Tribes of California (1876): "Most California Indians go now, and always have gone, barefoot; but some few were industrious enough to make for themselves moccasins of a very rude sort, more properly sandals. Their method of tanning was by means of brain-water. They dried the brains of deer and other animals, reduced it to powder, put the powder into water, and soaked the skins therein - a process which answered tolerably well. The graining was done with flints. Elk-hide, being very thick, made the best sandals."

The authors of the book, The Natural World of the California Indians (1980) have argued: "Hunters had to be physically clean if deer were to allow themselves to be shot, and so the hunter bathed, stood in fragrant smoke, avoided sexual contact for a certain period before he hunted, and thought pure thoughts. Where some, today, might say that a hunter purified himself to remove the human odor, which would alarm the deer, Indians would have said that that was the way the deer wished it if they were to permit themselves to be shot... A Wintu hunter had to possess two things. First was skill in stalking deer and the ability to use his bow. Second was what was called luck, by which was meant ensuring that the spirit of the deer was not offended by the failure of the hunter to go through the proper ritual preparation."

The ethnographer, Dorothy Demetrocopoulou, has argued that the Native American's relationship with nature was "one of intimacy and mutual courtesy. He kills for a deer only when he needs it for his livelihood, and utilizes every, part of it, hoof and marrow and hide and sinew and flesh: waste is abhorrent to him, not because he believes in the intrinsic virtue of thrift, but because the deer had died for him."

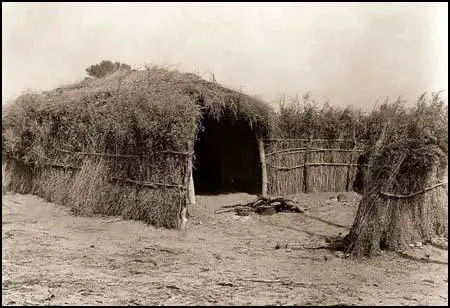

The Chahuilla lived between the San Bernardino Mountains and the Salton Sea in the Imperial Valley in Southern California, and close to the Mojave Desert. It has been estimated that in the 18th century there were about 2,500 Cahuilla living in California. According to Evelyn Wolfson, "they built long, narrow dome-shaped houses with straight sides covered with brush". The men hunted elk and deer in the mountains and trapped rabbits and other small animals in the foothills.

David Prescott Barrows studied the ethnobotany of the Cahuilla and recorded 60 plants they used for food and 28 for medicines. In his thesis, The Ethno-Botany of the Cohuilla Indians (1900) he argued: "A review of the food supply of these Indian forces in upon us some general reflections and conclusions. First, it seems certain that the diet was a much more diversified one than fell to the lot of most North American Indians. Roaming from the desert, through the mountains to the coast plains, they drew upon three quite dissimilar botanical zones... And yet this habitat, dreary and forbidding as it seems to most, is after all a generous one. Nature did not pour out her gifts lavishly here, but the patient toiler and wise seeker she rewarded well. The main staples of diet were, indeed, furnished in most lavish abundance."

Two tribes in Northern California were the Karok and Yurok. The word Karok means "upstream" and helped to distinguish them from the Yurok people who lived "downstream" on the Klamath River. Robert F. Heizer has argued that these two tribes were part of the Northwestern California subculture: "Ecologically, it was closely adapted to the rain-forest environment, with its settlements situated along river banks and the ocean coast at stream mouths, lagoons, or bays. The dugout canoe was the most important means of travel, routes being along rivers and the ocean shore. There were trails for foot travel, and these were used to visit neighboring villages; but the canoe remained the best means for travelling any distance and for crossing the Klamath River, which over much of its course is wide, fast-flowing, and deep."

The Miwok lived along the California coast between present day Santa Rosa and Monterey, and inland to the Sierra Nevada mountains. They also lived in the Yosemite Valley. They caught salmon and sturgeon from the rivers and streams and collected clams and mussels from the sea-shore. The Miwok also hunted deer and elk in the mountains and valleys. According to the authors of The Natural World of the California Indians (1980), they "observed the dictum that one did not overhunt, and they regulated the salmon fishing by ritual in such a way as to guarantee the continuance of the supply of fish in future years."

The Miwok did not plant crops but obtained most of their food from the acorns they collected each year. All acorns produced by California oaks contain tannin, which is very bitter. The Indians dealt with this problem by removing the acorn hull and to grind the interior into a flour in a stone mortar or on a flat grinding slab. They then constantly poured warm water over the flour to leach out the tannin. The leached flour was then mixed with water in a watertight basket and boiled by dropping hot stones into the gruel. The cooked mush was then either drunk or eaten with a spoon. Sometimes it was baked into a cake. In 1844 John C. Frémont saw an Indian village where near to each house was "a crate formed of interlaced branches and grass, in size and shape like a very large hogshead. Each of these contained from six to nine bushels of acorns."

Alfred L. Kroeber, an anthropologist, who spent some time living with Indian tribes in California, has argued in Handbook of the Indians of California (1919): "The cache or granary used by the Miwok for the storage of acorns is an outdoor affair, a yard or so in diameter, a foot or two above the ground, and thatched over, beyond reach of a standing person, after it was filled... The natural branches of a tree sometimes were used in place of posts. There was no true basket construction in the cache; the sides were sticks and brush lined with grass, the whole stuck together and fied where necessary. No door was necessary: the twigs were readily pushed aside almost anywhere, and with a little start acorns rolled out in a stream. Even the squirrels had little difficulty in helping themselves at will."

In 1542 Antonio de Mendoza, the new viceroy of New Spain, commissioned the experienced navigator, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, to lead an expedition up the California coast in search of trade opportunities and to find the Strait of Anián, purportedly linking the Pacific and the Atlantic. On 27th June, Cabrillo sailed from the port of La Navidad along the Mexican coast north of Acapulco, rounded the tip of the Baja Peninsula and then moved slowly north. On 12th August they entered a little bay. They found four Native Americans but they ran off when they approached.

The following month Cabrillo recorded that from his ship he saw "very beautiful valleys, groves of trees, and low, rolling countryside". He added that the mainland was "good land, by its appearance, with broad valleys and with mountains farther inland." Cabrillo also saw that large areas of land covered with dense smoke. It was later discovered that Native Americans in this part of California used this "aboriginal burning technique increased the harvest of acorns and grass seeds and improved the browse for deer, rabbits, and other animals".

On 28th September, Cabrillo anchored in San Diego Bay. Cabrillo and his men therefore became the first Europeans to reach California from the sea. Soon after landing Cabrillo encountered members of the Chumash tribe. They initially fled but when some of the men went ashore to fish with a net, some of them returned, armed with bows and arrows and fired at the Spaniards.

Two days later three members of the tribe approached Cabrillo's party and they managed a lengthy conversation in sign language. They reported that further inland there were bearded men dressed just like those on the ships, armed with crossbows and swords. According to the Indians, the bearded men had killed many natives. This was the reason why they had fired on the men fishing in the sea.

On 8th October they visited San Pedro Bay. Cabrillo described the place as "a good port and a good land with many valleys and plains and wooded areas." The following day they anchored overnight in Santa Monica Bay. Cabrillo recorded that the land was "more than excellent" and was the type of "country where you can make a settlement." Going up the coast Cabrillo saw Anacapa Island, 14 miles (23 km) off the coast, and spent the next few days in Cuyler Harbor on the island of San Miguel. On 13th November Cabrillo reached Point Reyes, but missed San Francisco Bay. Coming back down the coast, Cabrillo entered Monterey Bay on 16th November.

At the end of the year Cabrillo returned to San Miguel. However, on 24th December, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo fell and broke his arm near the shoulder (some sources say it was his leg). The wound grew gangrenous and just before his death on 3rd January, 1543, he requested his chief pilot, Bartolomé Ferrelo, to continue the expedition northward. On 1st March he reached latitude 42 degrees north, later the boundary between California and Oregon, before turning south and returning to La Navidad.

In 1577, a group of investors that included Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, Christopher Hatton, John Wynter and John Hawkins, decided to support a plan for Francis Drake to take a fleet into the Pacific and raid Spanish settlements there. Two years later, Drake's The Golden Hinde was leaking badly and needed to be careened. On 17th June 1579 Drake landed in a bay on the the coast of California. According to Drake's biographer, Harry Kelsey: "Sixteenth-century accounts and maps can be interpreted to show that he stopped anywhere between the southern tip of Baja California and latitude 48° N."

Father Francis Fletcher, the chaplin to the expedition, later wrote in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (1628): "Drake's ship entered a convenient and fit harbour." Drake has been reported as saying: "By God's Will we hath been sent into this fair and good bay. Let us all, with one consent, both high and low, magnify and praise our most gracious and merciful God for his infinite and unspeakable goodness toward us. By God's faith hath we endured such great storms and such hardships as we have seen in these uncharted seas. To be delivered here of His safekeeping, I protest we are not worthy of such mercy."

Most historians believe that Drake had stopped in a bay on the Point Reyes peninsula (now known as Drake's Bay). Drake's cousin, John Drake, argued that "Drake... landed and built huts and remained a month and a half, caulking his vessel. The victuals they found were mussels and sea-lions." A local group of Miwok brought him a present of a bunch of feathers and tobacco leaves in a basket. John Sugden, the author of Sir Francis Drake (1990) has argued: "It appeared to the English that the Indians regarded them as gods; they were impervious to English attempts to explain who they were, but at least they remained friendly, and when they had received clothing and other gifts the natives returned happily and noisily to their village." John Drake claims that when they "saw the Englishmen they wept and scratched their faces with their nails until they drew blood, as though this was an act of homage or adoration."

A local group of Miwok brought him a present of a bunch of feathers and tobacco leaves in a basket. John Sugden, the author of Sir Francis Drake (1990) has argued: "It appeared to the English that the Indians regarded them as gods; they were impervious to English attempts to explain who they were, but at least they remained friendly, and when they had received clothing and other gifts the natives returned happily and noisily to their village."

Francis Fletcher suggests that the local people "dispersed themselves into the country, to make known the news." On 26th June a large group of Miwok arrived at Drake's camp. The chief, wearing a head-dress and a skin cape, was followed by painted warriors, each one of whom bore a gift. At the rear of the cavalcade were women and children. A man holding a sceptre of black wood and wearing a chain of clam shells, stepped forward and made a thirty minute speech. While this was going on the women indulged in a strange ritual of self-mutilation that included scratching their faces until the blood flowed. Robert F. Heizer has argued in Elizabethan California (1974) that self-mutilation is associated with mourning and that the Miwok probably thought the British sailors were spirits returning from the dead. However, Drake took the view that they were proclaiming him king of the Miwok tribe.

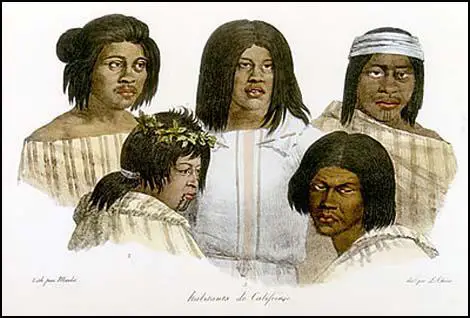

John Drake pointed out in a statement he made in 1582: "During that time (June, 1579) many Indians came there and when they saw the Englishmen they wept and scratched their faces with their nails until they drew blood, as though this was an act of homage or adoration. By signs Captain Francis Drake told them not to do that, for the Englishmen were not God. These people were peaceful and did no harm to the English, but gave them no food. They are of the colour of the Indians here (peru) and are comely. They carry bows and arrows and go naked. The climate is temperate, more cold than hot. To all appearance it is a very good country."

Drake now claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth. He named it Nova Albion "in respect of the white banks and cliffs, which lie towards the sea". Apparently, the cliffs of Point Reyes reminded Drake of the coast at Dover. Drake had a post set up with a plate bearing his name and the date of arriving in California.

Father Francis Fletcher wrote about the Miwok in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (1628): "Their men for the most part go naked, the women take a kind of bulrushes, and keeping it after the manner of hemp, make themselves thereof a loose garment, which being knitted about their middles, hangs down about their hips, and so affords to them a covering of that, which nature teaches should be hidden: about their shoulders, they also wear also the skin of a deer, with the hair upon it. They are very obedient to their husbands, and exceeding ready in all services."

When the The Golden Hinde left on 23rd July, the Miwok exhibited great distress and ran to the hill-tops to keep the ship in sight for as long as possible. Drake later wrote that during his time in California, "not withstanding it was the height of summer, we were continually visited with nipping cold, neither could we at any time within a fourteen day period find the air so clear as to be able to take height the sun or stars."

Drake then sailed along the California coast but like Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo before him, failed to see the Golden Gate and San Francisco Bay beyond. This is probably because the area is often shrouded in fog during the summer. The heat in the California Central Valley causes the air there to rise. This can create strong winds which pull cool moist air in from over the ocean through the break in the hills, causing a stream of dense fog to enter the bay.

The voyage across the Pacific Ocean could take as long as two hundred days and during that period most crews suffered a deadly toll of scurvy, dysentery and shipboard accidents. In the 1580s, Pedro Moya de Contreras, the viceroy of New Spain, commissioned the Portuguese adventurer, Sebastião Rodrigues Soromenho, to travel across the Pacific from the Philippines, to explore the coast of Alta California for possible ports. On 6th November, 1595, the San Agustín anchored in the same bay where the Golden Hinde had arrived in June 1579. He named the harbour the Bay of San Francisco. Soromenho continued to explore the coast but was shipwrecked close to Point Reyes on 30th November.

Another attempt was made seven years later. In 1601 the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City, the Conde de Monterrey, commissioned Sebastián Vizcaíno, a merchant-navigator, to locate safe harbours in Alta California for Spanish ships to use on their return voyage to Acapulco from Manila. He started his journey with three ships on 5th May, 1602. His flagship was the San Diego and on 10th November, he entered and named San Diego Bay. Vizcaíno explored his way up the coast naming most of the prominent features such as Point Lobos, Carmel Valley, Monterey Bay, Sierra Point and Coyote Point. Like Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and Francis Drake, Vizcaíno missed the entrance to San Francisco Bay.

Bad weather and scurvy forced him to return to Acapulco. Vizcaíno claimed that Monterey Bay would make the perfect harbour for galleons arriving from the Philippines. However, New Spain did not have the financial resources to establish a settlement so far to the north and nothing was done about Alta California for the next 167 years.

Inspector General José de Gálvez had been sent to New Spain with orders to organize the settlement of Alta California. Gálvez began to arrange what became known as the "Sacred Expedition". It was decided that three ships, the San Carlos, the San Antonio, and the San José, should sail to San Diego Bay. It was also agreed to send two parties to make an overland journey from the Baja to Alta California.

The first ship, the San Carlos, sailed from La Paz on 10th January, 1769. The other two ships left on 15th February. The first overland party, led by Fernando Rivera Moncada, left from the Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá on 24th March. With him was Father Juan Crespi, who had been given the task of recording details of the trip. Also in the party were 25 soldiers, and 42 Baju Christian Indians.

The overland expedition, led by Gaspar de Portolà was to include Junipero Serra. However, Portolà was concerned about the swelling of Serra's infected and tried to persuade him not to accompany the expedition: Serra replied that "I trust in God that he will give me strength to arrive at San Diego and Monterey." In order not to slow the party down, Serra suggested that Portolà should go on ahead. Francisco Palóu commented: "He said farewell, causing me equal pain for the love I felt for him and for the tenderness that I had owed him."

Serra, accompanied by two others, left on 1st April, 1769. "I undertook from my mission and the royal presidio of Loreto in California bound for the ports of San Diego and Monterey for the greater glory of God and the conversion of the pagans to our holy Catholic faith." He recorded that "I took along no more provisions for so long a journey than a loaf of bread and a piece of cheese." He reached Misson Santa Gertrudis on 20th April. Dionisio Basterra, was all alone at the mission. When Fernando Rivera Moncada had passed through he had requisitioned his interpreter, servant and guard. Serra remained with Basterra for five days.

On 28th April, after two days of strenuous travel, Serra arrived at Mission San Borja, where he was greeted by Fermin Francisco de Lasuén. Serra wrote: "My special affection for this excellent missionary detained me here for the next two days which for me were very delightful by reason of his amiable conversation and manners." Although it was in an isolated spot with a shortage of water, Lasuen had managed to convert several hundred Indian families living in the area.

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

On 1st May Junipero Serra joined up with Gaspar de Portolà at Santa Maria. Serra met the Cochimí people who had settled in this area. He was amazed that they were able to survive in the conditions. There was little water and virtually no arable land or pasture. On 11th May, Serra and Portolà, headed north and arrived in Velicatá two days later, where they met up with the advance guard of the party. Serra commented: "I praised the Lord, and kissed the earth, giving thanks to the Divine Majesty that after desiring this for so many years, He granted me the favour of being among the pagans in their own land."

Serra later recorded: "Then I saw what I could hardly begin to believe when I read about it or was told about it, namely that they go about entirely naked like Adam in paradise before the fall. Thus they went about and thus they presented themselves to us... Although they saw all of us clothed, they nevertheless showed not the least trace of shame in their manner of nudity."

Fernando Rivera Moncada and his party that included Juan Crespi reached San Diego on 14th May. He built a camp and waited for the others to arrive. The San Antonio, reached its destination in fifty-four days. The San Carlos took twice that time and the San José was lost with all aboard. The seaman on the ships suffered from scurvy and large numbers had died on the journey.

Junipero Serra left Father Miguel de la Campa to create a mission at Velicatá and the rest of the party moved on to San Juan de Dios. He was now having serious problems walking: "It was only with great difficulty that I could remain on my feet because my left foot had become very inflamed, a painful condition... Now this inflammation has reached halfway up the leg. It is swollen and the sores are inflamed. For this reason the days during which I was detained there I spent the greater part in bed."

Gaspar de Portolà pleaded with him to remain but Serra insisted on going on: "Please do not speak of that, for I trust that God will give me the strength to reach San Diego, as He has given me the strength to come so far... Even though I might die on the way, I shall not turn back. They can bury me wherever they wish and I shall gladly be left among the pagans, if it be the will of God." Eventually it was agreed that he should be carried along the trail by the Christian Indians from Baja California.

Serra received treatment from one of the soldiers, Juan Antonio Coronel. He heated some tallow and green desert herbs and spread the mixture over Serra's foot and leg. He later told Francisco Palóu: "God brought it about (through Coronel) and I was enabled to make the daily trek just as if I did not have any ailment. At present my sore foot is as clean as the well one."

Gaspar de Portolà recorded in his diary: " The 11th day of May, I set out from Santa Maria, the last mission to the north, escorted by four soldiers, in company with Father Junipero Serra, president of the missions, and Father Miguel Campa. This day we proceeded for about four hours with very little water for the animals and without any pasture, which obliged us to go on farther in the afternoon to find some. There was, however, no water."

On 26th May, 1769, some of the party's Christian Indians, captured a man who had been following them along the route. Junipero Serra immediately ordered the man to be released and fed him with figs, meat, tortillas and atole (a thin porridge of corn and wheat). He told them his name was Axajui and that he was a member of a tribe who were planning to ambush and kill the missionaries and soldiers. Axajui was sent back to inform his people of the good treatment he had received. The strategy worked as they were allowed to continue on their journey unharmed.

Serra also recorded that a few days later they were approached by a couple of women: "I desired for the present not to see them (fearing that they went naked like the men)... When I saw them so decently clothed... I was not sorry at their arrival... They were talking as rapidly and effectively as this sex knows how and is accustomed to." The women offered the men some "doughy pancakes" that they had been carrying on their heads.

As the expedition moved on through the month of June, the terrain became gradually more attractive. Junipero Serra noted at Santa Petronilla that the land was "so loaded with grapes that it is a thing to marvel at. I believe that with a little labour of pruning them, the vines would produce much excellent fruit." On the 20th they saw the Pacific in the distance. That night they arrived on the shores of Ensenada. Serra commented: Here, if the water could be properly utilized, great plantings could be made and enough water was at hand to supply a city." The party was now only 65 kilometres (40 miles) south of San Diego.

On 23rd June the party met a large party of Native Americans. Serra records: "The people were healthy and well built, affable, and of happy disposition. They were quick, bright people, who immediately repeated all the Spanish words they heard. They danced for the party, offered fish and mussels, and pressed them to remain... We were all enamored of them. In fact, all the pagans have pleased me, but these in particular have stolen my heart."

José Francisco Ortega, chief scout of the party, went on ahead to San Diego. He arrived back on 28th June, with news that the last leg of the journey was extremely difficult due to the hundreds of gullies they still had to cross. Serra later told Francisco Palóu that he crossed each one with a prayer on his lips. When he arrived at San Diego Bay Serra was reunited with Fernando Rivera Moncada and Gaspar de Portolà, who had gone ahead.

Junipero Serra later recalled: "It was a day of great rejoicing and merriment for all, because although each one in his respective journey had undergone the same hardships, their meeting through their mutual alleviation from hardship now became the material for mutual accounts of their experiences. And although this sort of consolation appears to be the solace of the miserable, for us it was the source of happiness. Thus was our arrival in health and happiness and contentment at the famous and desired Port of San Diego."

Gaspar de Portolà was named as governor of San Diego. Junipero Serra was impressed with the area. As Don Denevi, the author of Junipero Serra (1985), has pointed out: "Reconnoitering the grassy plains around Presidio Hill where the expedition was encamped, the padres noted that fresh water and arable land were plentiful. Fields could be sown with grain, fruits, and vegetables. Willow, popular, and sycamore trees dotted the river banks. Wild grapevines, asparagus, and acorns grew in abundance. Deer, antelope, quail, and hares were abundant, as were the more ferocious wolves, bears, and coyotes. In addition to the abundance of food on land, the Indians, from rafts made of tules, fished for sole, tuna, and sardines and gathered mussels."

Portolà and his expedition, consisting of Father Juan Crespi, Fernando Rivera Moncada, José Francisco Ortega, Pedro Fages, sixty-three soldiers and a hundred mules loaded down with provisions, headed north on 14th July, 1769. Portolà reached the site of present day Los Angeles on 2nd August. The following day, they marched to what is now known as Santa Monica. Later that month they arrived at what became Santa Barbara, Portolà's party walked across the Santa Lucia Mountains to reach the mouth of the Salinas River. The fog obscured the shore and they therefore missed reaching Monterey Bay. The men had walked over a thousand miles from Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá.

While they had been away Junipero Serra had been organising the building of Mission San Diego de Alcalá on Presidio Hill in honour of Saint Didacus. Serra wrote about his motivation for the Franciscans establishing these missions: "Above all, let those who are to come here as missionaries not imagine that they are coming for any other purpose but to endure hardships for the love of God and the salvation of souls, for in far-off places such as these, where there is no way for the old missions to help the new ones because of the great distance between them, the presence of pagans, and the lack of communication by sea, it will be necessary in the beginning to suffer many real privations."

The settlement was close to a Kumeyaay village. Tracy Salcedo-Chouree, the author of California's Missions and Presidios (2005), has pointed out that their "natural suspicion flowered into animosity when the soldiers began raping their women and stealing their food." On 15th August, the colonists came under attack. One of the Spanish settlers was killed during the raid. Junipero Serra recorded what happened: "He entered into my little hut with so much blood streaming from his temples and mouth that shortly after I gave him absolution... he passed away at my feet, bathed in his blood. And it was just a short time after he died before me that the little hut where I lived became a sea of blood. All during this time, the exchange of shots from the firearms and arrows continued. Only four men of our group fired while more than twenty of theirs shot arrows. I continued to stay with the departed one, thinking over the imminent probability of following him myself, yet, I kept begging God to give victory to our Holy Catholic faith without the loss of a single soul."

The battle for San Diego, the first in the Spanish settlement of California, changed the relationship between the settlers and the Kumeyaay. They now became more peaceful and began revisiting the camp, bringing along their wounded, probably hoping that Spanish remedies would prove as powerful as Spanish arms. Don Pedro Prat, who had received some medical training, did what he could do to help the wounded men brought to the settlement.

Gaspar de Portolà and his men reached the San Francisco Bay area on 31st October. It has been claimed that José Francisco Ortega, his chief scout, was the first European to see the bay. He explored and named many localities in the region. Running short of provisions and forced to live on mule meat, they decided to return to San Diego to replenish supplies. They arrived back on 24th January, 1770, remarkably, every member of the expedition had survived. Portolà and Juan Crespi had recorded the places they had stayed, the tribes they had met, possible mission sites, and the animals and widflowers found.

Inspector General José de Gálvez had sent orders that their next task was to locate Monterey Bay. On 16th April, 1770, Junipero Serra, left the San Diego harbour on the San Antonio. The following day, Portolà's land expedition, that included Father Juan Crespi and Pedro Fages marched north. José Francisco Ortega was left in charge of the Mission San Diego de Alcalá.

Portolà successfully arrived at Monterey Bay on 24th May, 1770. A three-man party was sent out to explore the rocky coast south to Carmel Bay. A few days later the San Antonio arrived in the bay. The journey had been slow and difficult. Over the next few days Serra began planning the building of Mission San Carlos de Borromeo, named in honour of Saint Charles Borromeo. Portolà left Fages behind to establish a settlement that they called California Nueva (New California). During this time, Fages explored by land San Francisco Bay, San Pablo Bay, the Carquinez Strait and the San Joaquin River.

On 9th July, 1770, Gaspar de Portolà sailed from Monterey Bay on the San Antonio. He left forty men in charge of Spain's latest settlement. Junipero Serra remained in Monterey. Carlos Francisco de Croix wrote that Serra: "The President of those missions, who is destined to serve in Monterey, states in a very detailed way and with particular joy that the Indians are affable. They have already promised him to bring their children to be instructed in the mysteries of how holy Catholic religion." It was not until 26th December, 1770, that Serra baptised his first Native American in California.

In 1772, a party of sailors and missionaries, including Pedro Fages and Juan Crespi set out to explore the coast of California. Crespi later described that when they arrived at San Pablo Bay they were approached by Native Americans (probably Costanoans): "When we arrived at this place there came to us eight Indians bringing as gifts wild seeds, as the others had done; in front, an Indian dancing, with a great bunch of feathers on his head, a pipe in his mouth, in one hand a banner of feathers, and a net. These things they presented to the captain. We gave them glass beads. They stayed with us quite a while and went back well content. They are very peaceable and agreeable, and it pleased us greatly that with their beards and light colouring they looked like Spaniards."

After making a full investigation of the area Crespi reported back that without finding a good overland route to San Francisco it would be difficult to establish a mission in the area: "From all that has been seen and learned, it follows that if the new mission should be established at the harbour itself or in its near vicinity, its animals and supplies could not come to it or be brought to it by land; nor, once it were founded, could there be any communication between it and this mission of Monterey or any others that may be founded in this direction, unless a pair of good longboats are supplied, with sailors, for getting persons from one side to the other."

In August 1772, the supply ships had difficulty getting to Monterey. Serra wrote to Francisco Palóu: "All the missionaries grieve - we all grieve - over the vexations, labours, and reverses we have to put up with. No one, however, desires to leave his mission. The fact is, labours or no labours, there are several souls in heaven from Monterey, San Antonio, and San Diego."

Eventually, Serra took a party down to San Diego, a 500 mile journey, to bring back food. On the journey, Serra created California's fifth mission, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, on a site located halfway between Santa Barbara and Monterey. It was named after Saint Louis of Anjou, the bishop of Toulouse. Serra left Father Cavaller, a four-man guard, and two Baju California Indians, at the mission and moved on. The party was attacked by a Chumash tribe in the San Luis Valley. Fages and his men fought off the warriors, and to Serra's distress, one of them were killed. They safely got to San Diego and managed to arrange a supply ship to Monterey.

Junipero Serra had a difficult relationship with Pedro Fages, the commander of Monterey. He was also disliked by his troops. One soldier wrote that: "The commandante used to beat us with cudgels; he would force us to buy from him at three times their value, the figs and raisins in which he was trading; he would make sick men go and cut down trees in the rain and would deprive them of their supper, if they protested; he would put us all on half rations even though food might be rotting in the storehouse. We had to live on rats, coyotes, vipers, crows, and generally every creature that moved on the earth, except beetles, to keep from starvation. We almost all became herbivorous, eating raw grass like our horses. How many times we wished we were six feet under ground."

Serra decided to visit Antonio María de Bucareli, the new viceroy of New Spain, in Mexico City. He left in October 1772, with his servant, Juan Evangelista. He did not arrive at the College of San Fernando de Mexico on 6th February, 1773. Bucareli asked Serra to put all his requests in writing. He gave the viceroy this document on 13th March. It was in fact a "Bill of Rights" for the Native Americans.

Junipero Serra also asked for the removal of Pedro Fages. Bucareli granted the request. He later commented: "The dispute with Don Pedro Fages... compelled Father Fray Junipero Serra almost in a dying condition to come to this capital to present his requests and to inform me personally a thing which rarely can be presented with such persuasion in writing. On his arrival I listened to him with the greatest pleasure and I realized the apostolic zeal that animated him while I accepted from his ideas those measures which appeared proper to me to carry out."

Don Denevi, the author of Junipero Serra (1985), has argued: "Serra could reflect on a number of achievements: the promise of expeditions to explore and open up overland routes from Sonora and new Mexico; the separate marking of mission and military goods; the removal of immoral soldiers from the missions at the padres' request; the regulation of prices and standardization of weights; the recruiting of Mexicans on sailors' pay to the missions' fields; the protection of the padres' mail from tampering by military commanders; the provision of a doctor, blacksmiths, and carpenters, and of bells and vestments for the new missions; serious consideration of the shortage of mules; and pardons for all deserters."

Junipero Serra returned to Carmel in September 1773. He was now nearly sixty years old and in poor health. He had decided that he would never return to Spain to see his family: "California is my life and there, God willing, I hope to die." He wrote to his nephew Miquel: "Although I am lukewarm, bad, and unprofitable, yet every day in the holy sacrifice of the Mass, I always make a memento for my only and most beloved sister Juana, your mother, and for her children... I hope all of you do the same for me so that the Lord may assist me amid the perils of a naked and barbarous people."

Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli asked Juan Bautista de Anza to explore the land north of New Spain. On 8th January, 1774, he left Tubac with Franciscan missionary, Francisco Garcés and 34 soldiers. Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has argued: "Captain Anza - a longtime veteran of frontier service with an outstanding reputation - set forth from the presido at Tubac, south of the present-day city of Tucson, with thirty-four soldiers and one Franciscan, Francisco Garcés, himself an experienced explorer." Anza reached Mission San Gabriel on 22nd March, 1774. He then marched north to Monterey before returning to Tubac. As Starr has pointed out: "In one heroic trek, Anza had linked California overland to northern New Spain." Bucareli was impressed with Anza's achievements and promoted him to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

On 24th January 1774, Serra took 97 people from San Blas on the Santiago to Monterey. This included two doctors, three blacksmiths, and two carpenters, some with wives and children. This was as a result of the arrangement reached with Antonio María de Bucareli. Serra believed this would enable him to build a permanent Spanish community in this part of California. Serra left at San Diego and walked the rest of the journey to Monterey so that he could see for himself the progress that his missions were making. This included visits to the missions at San Diego de Alcalá, San Gabriel Arcangel, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and San Antonio de Padua.

Serra arrived back at Mission San Carlos de Borromeo on 11th May, 1774. He was greeted warmly by Francisco Palóu and Juan Crespi who were now both stationed in Monterey. When he left, there had been twenty-two baptisms since the founding of the mission; on his return, the total was one hundred seventy four. Serra was extremely happy about the progress that had been made in his absence.

In a letter he wrote on 24th August, 1774, Junipero Serra explained that: "Every day Indians are coming in from distant homes in the Sierra... They tell the padres they would like them to come to their territory. They see our church which stands before their eyes so neatly; they see the milpas with corn which are pretty to behold; they see so many children as well as people like themselves going about clothed who sing and eat well and work." Serra wrote that he was especially pleased with the impact the missionaries were having on the children: "The spectacle of seeing about a hundred young children of about the same age praying and answering individually all the questions asked on Christian doctrine, hearing them sing, seeing them going about clothed in cotton and woolen garments, playing happily and who deal with the padres so intimately as if they had always known them."

Antonio María de Bucareli selected Juan José Pérez Hernández to lead an expedition to explore the coast of the northwest. Crespi went along as his chaplain and diarist. The Santiago left Monterey on 11th June, 1774. The ship sailed as far north as Langara Island, one of the Queen Charlotte Islands. They were unable to go ashore and a lack of provisions and the poor health of his crew, meant that Pérez headed back to the Spanish settlement in Monterey, which he reached on 27th August.

Junipero Serra encouraged the Spanish sailors and soldiers to marry local women. He wrote that three of them had done so and that three others were considering the prospect. If they colonised the area, they received two years' pay and food rations for five years for themselves and their families. Serra believed that unless colonists began to live permanently near the mission, the missions would never become formal settlements.

Antonio María de Bucareli appointed Fernando Rivera Moncada as the new commander of Monterey. Junipero Serra, who had worked with Rivera previously, welcomed the decision. Michael Hardwick has argued: "Rivera showed the most scrupulous honesty in administering presidio accounts. His penmanship was firm and distinguished. His ideas were expressed economically and with conviction in a terse and businesslike style. While governor of California, Rivera made every effort to improve the material conditions of the presidio of Monterey. He pleaded for more animals – more cows for milk and meat, more horses and mules to haul supplies from ships to the warehouse, to distribute them among the missions, and to patrol the vast territory. Rivera tried to secure better weapons and worked out a signal system in order to distinguish Spanish ships from hostile intruders. He insisted on regular attendance at religious services and attended regularly himself at the Monterey presidio chapel."

However, it was not long before the relationship between Rivera and Serra began to disintegrate. The main problem was that Rivera did not share Serra's passion for building new missions in the area. Serra wrote: "What are we doing here since it is plain that with this man in charge, no new missions will ever be established." Serra complained that the first mission south of San Carlos de Borromeo was San Antonio de Padua, nearly 70 miles away. Beyond was San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, another 75 miles to the south. The next mission was San Gabriel Arcangel, 212 miles away. The final mission, San Diego de Alcalá, was another 116 miles along the coast. Serra argued that these gaps needed filling in. He envisioned ten or eleven California missions being developed in his lifetime, "on a ladder with conveniently placed rungs". With missions founded at suitable intervals, travellers would spend only two or three days in the open between them.

Serra argued that these gaps needed filling in. He envisioned ten or eleven California missions being developed in his lifetime, "on a ladder with conveniently placed rungs". With missions founded at suitable intervals, travellers would spend only two or three days in the open between them. Serra was given permission to build these missions but Rivera refused to supply the soldiers to protect the missionaries. Rivera argued that: "I have never seen a priest more zealous for founding missions than this Father President. He thinks of nothing but founding missions, no matter how or at what expense they are established."

Junipero Serra also complained about lack of resources. He wrote that: "To clothe the nakedness of so many girls and boys, women and men, even moderately, not only to protect them from the cold, which is quite severe here during the greater part of the year, but also to foster decency and urbanity especially among the weaker sex, I am confronted with an almost insuperable difficulty."

In 1774 the missionaries based in San Diego moved about six miles inland from the Presidio to take advantage of more productive farmland and a better source of water. Luis Jayme, a priest from Sant Joan, Majorca, organised the building of the Mission San Diego de Alcala. It is claimed that they converted more than 500 local people to Christianity.

However, at the sametime, Serra was hearing bad news about his mission in San Diego. Father Vincentre Fuster had ordered the flogging of some members of the Kumeyaay tribe for attending a pagan dance. He also threatened to set fire to their village if they continued to behave in this way. The result of this warning was to make some of these people to runaway to join Chief Carlos, who was calling for an attack on the Spanish missions.

On 4th November, 1775, Chief Carlos and over 600 members of the Kumeyaay approached the Mission San Diego de Alcala. At first they surrounded the huts of the Christian Indians, threatening them with death if they tried to escape. They then crept into the church and stole the statues and other objects they thought might be of some worth. Soon afterwards they began setting fire to the buildings in the mission.

Vincentre Fuster jumped from his bed and raced towards the soldiers barracks, where he found the troops already firing their muskets. By this time two of the soldiers and the carpenter, had been hit by arrows and were gravely wounded. Fuster later told Junipero Serra: "It is impossible to estimate the number of arrows that were aimed at my head and which terminated their flight in the adobes, but thanks be to God not a single one hit me." Fuster told the men trapped in the barracks: "Let us truly ask this Holy Mother to favor us, to repress the fury of our enemies, and to allow us to be victorious over them. To obtain this favor, I on my part promise to fast nine Saturdays and to celebrate nine holy Masses in her honor."

Luis Jayme refused to seek protection and instead walked calmly towards the warriors, chanting, "love God, my children". According to Francis J. Weber: "Instead of running for shelter to the stockhold, Fray Luís Jayme resolutely walked toward the howling band of natives... In a frenzied orgy of cruelty, the Indians seized him, stripped off his garments, shot eighteen arrows into his body and then pulverized his face with clubs and stones... Early the next morning, the body of the thirty-five year old missionary was recovered in the dry bed of a nearby creek. His face was so disfigured that he could only be recognized by the whiteness of his flesh under a thick crust of congealed blood." Luis Jayme is considered to be the first Catholic martyr in Alta California.

Fuster recorded: "Great was my sorrow when I laid my eyes upon his person for I saw him totally disfigured... I saw that he was entirely naked except for the drawers that he wore, his chest and body pitted like a sieve from the savage blows of the clubs and stones. Finally, I recognized him... only insofar as my eyes noted the whiteness of his skin and the tonsure of his head. It is fortunate that they did not scalp him as is customary among these barbarians when they kill their enemies."

Fernando Rivera Moncada was given responsibility for investigating the rebellion. On 27th March, 1776, he was discovered hiding behind the altar in the church at the Mission San Diego de Alcala. Rivera and his soldiers surrounded the church. They entered the chapel and seized Carlos and after dragging him from the church he was put in the guardhouse. Father Vincentre Fuster protested loudly against the action and shouted that all those participating in the arrest were now excommunicated. Junipero Serra, who argued that as Carlos had sought refuge in the church, Fuster was right to excommunicate Rivera.

The San Gabriel Arcangel also experienced problems with local tribes. The wife of an Indian chief from a nearby village was raped by one of the mission soldiers. The chief tried to kill the soldier but the arrow bounced off the man's leather shield. The chief was captured and his head cut off and impaled upon a pole to warn off other members of his tribe. After the intervention of the missionaries, the warriors were persuaded not to take revenge on the Spanish.

Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli decided to establish another Spanish settlement in San Francisco. On 26th July, 1775, he sent Juan de Ayala, the captain of the San Carlos, to explore the San Francisco area by sea. He took with him Vicente de Santa Maria, who was to be his diarist. The San Carlos left Monterey on 26th July, 1775. Rand Richards, the author of Historic San Francisco (1991) has pointed out that Ayala had a serious accident on the journey: "He was nursing what must have been a very painful wound, having accidently been shot in the foot several weeks into the voyage when a loaded pistol discharged as it was being packed away."

The San Carlos reached San Francisco Bay on 5th August. He therefore became the first European to sail through the Golden Gate. He anchored his vessel near present-day Fort Point. Ayala later reported: "From the shore's edge, some Indians begged us with the heartiest of shouts and gesticulations to come ashore. Accordingly I sent over to them in the longboat the reverend father chaplain (Vicente de Santa Maria), the first sailing master, and some men under arms, with positive orders not to offend the Indians but to please them, taking them a generous amount of earrings and glass beads. I charged our men to be discreetly on their guard, keeping the longboat ready to pull out if any quarrelling started, and I told the sailing master to leave four men in it under arms."

Vicente de Santa Mariarecorded in his journal: "Before the longboat had gone a quarter of a league it came across a rancheria of heathen who, seeing that our people were close by, left their huts and stood scattered at the shore's edge. They were not dumfounded (though naturally apprehensive at sight of people strange to them); rather, one of them, raising his voice, began with much gesticulation to make a long speech in his language, so outlandish that none of it could be understood. At the same time, they were making signs for the longboat to come near, giving assurance of peace by throwing their arrows to the ground and coming in front of them to show their innocence of treacherous dissimulation. But if danger showed not its face to the officer, he saw at least the shadow of risk to his men and did not wish to approach any nearer than was necessary for the discharge of his duty. The Indians, guessing that our men were somewhat suspicious, tried at once to make their intentions clear. They took a rod decorated with feathers and with it made signs to our men that they wished to make them a present of it; but since this met with no success they decided on a better plan, which was to draw back, all of them, and leave the gift stuck in the sand of the shore near its margin. The longboat turned back for the ship, leaving the gift untaken and reporting that the place was not as it had been thought."

The longboat returned and this time it was the Native Americans (probably Costanoans) who ran away: "The armed Indians, on seeing our men close by, hid themselves (perhaps in fear) among what oak trees they could find that would give them cover... Having reached the shore, he came upon a collection of things which, though to our notion crude, was of high value to those unfortunates, for otherwise they would not have chosen it as the best offering of their friendly generosity. This was a basketful of pinole (who knows of what seed?), some bunches of strings of woven hair, some of flat strips of tule, rather like aprons, and a sort of hairnet for the head, made of their hair, in design and shape best described as like a horse's girth, though neater and decorated at intervals with very small white snailshells. All this was near a stake driven into the sand. Limited though it was, we did not hold this unexpected friendly gift of little value; nor would it have been seemly in us to be contemptuous of a present that showed the good will of those who humbly offered it."

The following day the longboat returned with their own gifts. Vicente de Santa Maria recorded in his journal: "Our captain, touched by this indication of regard, showed on receiving it with respect a just acknowledgement of its worth. Therefore it was decided that very early the next morning the longboat should return the basket in which the Indians had given us their pinole, and in it trinkets made with bits of glass, earrings, and glass beads, our captain having first directed the officer in charge of the longboat to replace the stake and return the basket to the same place as before, very quietly, and at once return to the ship. This was done as ordered, and although there were some heathen near by, our men pretended not to have taken notice of their presence. These Indians acted almost wonderstruck at so prompt and special a return of favours, marvelling at the sight of the things sent from the ship."

Ayala spent most of the time in the bay anchored off Angel Island. He kept a detailed log of the party's activities and named two of its landmarks: Sausalito ("little thicket of willows") and Alcatraz ("island of pelicans"). Ayala was awaiting the arrival of Juan Bautista de Anza, but after 44 days in the bay he decided to return to Monterey.

Juan de Ayala reported back that he was impressed by San Francisco harbour: "This is certainly a fine harbour: it presents on sight a beautiful fitness, and it has no lack of good drinking water and plenty of firewood and ballast. Its climate, though cold, is altogether healthful and it is free from such troublesome daily fogs as there are at Monterey, since these scarcely come to its mouth and inside there are very clear days. To these many good things is added the best of all: the heathen all round this harbour are always so friendly and so docile that I had Indians aboard several times with great pleasure, and the crew as often visited them on land. In fact, from the first day to the last they were so constant in their behaviour that it behove me to make them presents of earrings, glass beads, and pilot bread, which last they learned to ask for in our language clearly."

Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli selected Juan Bautista de Anza to lead the overland party to San Francisco Bay. He was authorized to colonize the San Francisco Bay area. He recruited colonists from among the poor in Culiacan. The expedition left Tubac on 23rd October, 1775, with 245 people (155 of them women and children), 340 horses, 165 pack mules and 302 cattle for breeding stock. Pedro Font, a Franciscan priest was selected to accompany this expedition, because of his expertise with navigation.

Anza's expedition headed north down the Santa Cruz River, arriving in Tucson on 26th October. They then followed the Gila River west, to arrive at the Colorado River and a reunion with Chief Salvador Palma, and members of the Quechan tribe on 28th November. After crossing the Colorado, the expedition broke into 3 groups so that everyone could drink from the slow-filling desert water holes. After crossing the Sonoran Desert they reached Yuha Wells on 11th December.

After experiencing a freak desert snowstorm that resulted in the death of some of their livestock, they headed up Coyote Canyon, going through San Carlos Pass on 26th December. They reached Mission San Gabriel on 4th January. Since leaving Culiacan they had been travelling for over eight months. Anza had succeeded in taking his expedition through 1,800 miles of desert wilderness.

On 17th February 1776, Anza and his expedition began their march north, reaching Monterey on 10th March. Anza arrived in California with two more people than he had left with. Three children were born along the way; one woman died in childbirth. While the colonists remained in Monterey, José Joaquín Moraga and Pedro Font, and a small group of soldiers, went ahead. On 28th March, they reached the tip of the peninsula (now named Fort Point) where Anza planted a cross signifying the place where he thought the presido should be built. Father Font, wrote in his journal that night: "I think that if it could be well settled like Europe there would not be anything more beautiful in all the world."

Rand Richards, the author of Historic San Francisco (1991) has pointed out: "While the site for the presido was perfect for its strategic value, the windswept, rocky ledge was less than ideal for a mission settlement. So the next day, after exploring further, the small band came upon a sheltered valley three miles inland to the southeast. Here the soil and climate were better and there was abundant fresh water provided by a stream-fed lagoon."

Juan Bautista de Anza returned to New Spain and left behind José Joaquín Moraga to establish the Spanish settlement in the area. On 17th June, the colonists left Monterey to join Mortaga in San Francisco. The Mission San Francisco de Asís, a log and thatch church was completed on 29th June, 1776. The mission was composed of adobe and redwood and was 144 feet long and 22 feet wide. Francisco Palóu, a former student of Father Junipero Serra, was placed in charge of the mission that had been dedicated to San Francisco de Asis. It was about 3 miles from the Golden Gate. The surrounding houses, a pueblo, became known as Yerba Buena. It was named after a sweet-smelling minty herb that grew wild in the area.

The Spanish also built a Presido at San Francisco. According to Tracy Salcedo-Chouree, the author of California's Missions and Presidios (2005): "The Presidio of San Francisco started out much as other Spanish settlements - a cluster of brush and tule huts surrounded by a palisade that housed, according to one historian, about forty soldiers and nearly 150 settlers. Adobe would replace wood and mud within a few years, with a chapel, a guardhouse, officers' residences, barracks, warehouses, and other buildings forming a square protected by a defensive wall."

Antonio María de Bucareli began to favour Junipero Serra over Fernando Rivera Moncada. In 1777 he replaced Rivera with Don Felipe de Neve. Rivera was now transferred to Loreto in California as lieutenant governor. At Neve’s request, Teodoro de Croix, Captain General of the Interior Provinces ordered Rivera, to recruit soldiers and settlers for the founding of Los Angeles.

Serra visited Mission San Francisco de Asís at San Francisco for the first time in September 1777. It gave him the opportunity to meet up with his friend, Francisco Palóu, who was running the mission. Afterwards he wrote: "Thanks be to God. Now Our Father Saint Francis, the crossbearer in the procession of missions, has come to the final point of the mainland of California; for in order to go farther, ships will be necessary."

The following month they were together at the Mission Santa Clara de Asis, a mission that had been established earlier that year. Palóu wrote that Serra was not in good health: "He arrived in such a condition that he could hardly stand. Nor could it be be otherwise since he had walked seventy-one miles in two days. When the officers and the surgeon saw the inflammation of the leg and the wound of the foot, they declared that it was only a miracle that he could walk."

The Spanish Government was eager to establish an overland link between California and New Spain and needed to establish a presence to protect point where travelers would ford the Colorado River. In January, 1781, Father Francisco Garcés established the Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer. However, unlike the missions established by Junipero Serra, the powers of administration rested with the military and not with the padres, as a result the soldiers were abusive to the local Native Americans. Spanish colonists were also accused of seizing the best lands in the area. This caused conflict with the Native Americans.

In the summer of 1781, Fernando Rivera Moncada and a small group of soldiers advanced across the desert with a vast herd of animals, estimated to nearly 1,000 in number. On 17th July, while camped on the banks of the Colorado near Yuma, Rivera and his men were killed by a surprise attack by the Quechan tribe. They then went on to kill Francisco Garcés and the other missionaries at the Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer. The mission was never re-established and the overland route to Alta California was considered too hostile to be used and was therefore abandoned.

Pedro Fages, the new governor of California, soon came into conflict with Junipero Serra over the building of new missions. In 1783 he wrote to the former governor, Felipe de Neve: "The opposition of Father Serra to every government measure is already manifest and has been signified not only in words but in actions and writings... Father Serra walks roughshod over our measures, conducting himself with great despotic spirit and with total indifference".

Junipero Serra died on 28th August, 1784, at the age of 70. Fermin Francisco de Lasuén became the new President of the Californian missions. Francis F. Guest wrote: "Junipero Serra and Fermin Francisco de Lasuen, in many respects, were opposites. Both were highly intelligent, yet Lasuen, gifted with a degree of perceptiveness to which Serra could not lay claim, easily surpassed him in human relations. Serra was more learned in theology, in which he had a doctors degree; but Lasuen, though lacking the erudition of the first Father President, was endowed with greater psychological insight. Both excelled as administrators, vet, here too, Lasuen revealed a flexibility, a subtlety, a suppleness which Serra did not manifest."

On 14th September, 1786, Jean-François de Galaup de la Pérouse, the French explorer, landed at Monterey. He wrote in his journal: The sea is fairly rough and one can only stay a few hours in such an anchorage, waiting for daylight or a break in the fog... One cannot put into words the number of whales that surrounded us nor their familiarity; they blew constantly, within half a pistol shot of our frigates, and filled the air with a great stench."

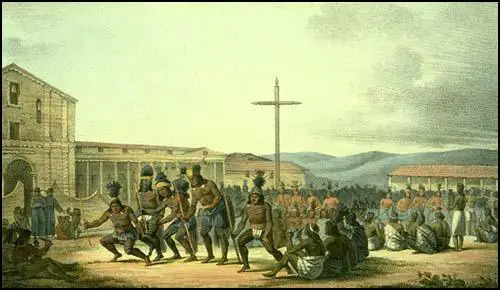

La Pérouse visited Fort Loreto, the Presidio of Monterey: "Loreto is the only Presidio of the Old California on the East coast of this peninsula; it has a garrison of 54 cavalrymen who supply small detachments to the following 15 missions, which are in the care of the Dominican Fathers who succeeded the Jesuits and the Franciscans; the latter have remained in sole charge of the ten missions of New California." In his journal he commented that the Spanish had built 15 missions in California. He argued: "I have already made known my opinion that the way of life of the people who have been converted to Christianity would be more favourable to a growth in population if the right of property and a certain freedom formed the basis of it; however, since the ten mission stations were set up in Northern California, the Fathers have baptised 7701 Indians of both sexes and have buried only 2388. But it must be stressed that this calculation does not indicate, as in European cities, whether the population is growing or not, because they baptise Independent Indians every day; the only consequence is that Christianity is spreading, and I have already said that the matters of the next life could not be in better hands."

The Spanish missionaries had some success at converting local Native Americans to Christianity and by 1794 the population of Mission San Francisco de Asís had reached 1,000. These people became known as neophytes. They were not always treated well by the missionaries. Padre José Maria Fernandez reported that large numbers left because of the "terrible suffering they experienced from punishments and work". The neophytes were very vulnerable to disease and in 1795 a measles epidemic killed large numbers. More than 200 fled the mission during the outbreak.

Father Miguel Hidalgo was a priest in Dolores, New Spain. An highly educated man, he used his knowledge to promote economic activities for the poor and rural people in his area. He established factories to make bricks and pottery and taught mestizos and local indians how to produce leather. His main objective was to make them more self-reliant and less dependent on Spanish economic policies. However, these activities violated policies designed to protect Spanish peninsular agriculture and industry, and Hidalgo was ordered to bring an end to this education system.

Hidalgo now established an alternative government in Guadalajara. On 16th September, 1810, Hidalgo declared independence from Spain. This was followed on 6th December by a decree abolishing slavery. He also abolished tribute payments that the Indians had to pay to their Spanish lords. Hidalgo also ordered the publication of a newspaper called Despertador Americano (American Wake Up Call).

Father José María Morelos, a mestizo, became leader of the military campaign. In the first nine months of the Mexican War of Independence, he won 22 victories, destroying the armies of three Spanish royalist leaders. In December, 1810, he took control of Acapulco.

Miguel Hidalgo was captured on on 21st March 1811 and taken to the city of Chihuahua. He was then found guilty of treason by a military court and executed by firing squad on 30th July. His head was cut off and displayed on the four corners of the Alhondiga de Granaditas.

Morelos now became the leader of the independence movement. The Spanish Army, under the leadership of General Félix María Calleja del Rey, besieged Morelos and his soldiers at Cuautla. On 2nd May, 1812, after 58 days, Morelos broke through the siege. Morelos arrived at Orizaba with 10,000 soldiers on 28th October 28. The city was defended by 600 Spanish soldiers. Negotiations resulted in a Spanish surrender without bloodshed.

On 13th September, 1813, the National Constituent Congress of Chilpancingo, endorsed Morelos' "Sentiments of the Nation" document that declared Mexican independence from Spain. It also abolished slavery and racial social distinctions in favor of the title "American" for all native-born individuals. Torture, monopolies and the former system of taxation were also abolished.

José María Morelos was defeated at Tezmalaca in November 1815. He was taken prisoner and brought to Mexico City in chains. He was tried and executed for treason on 22nd December, 1815 in San Cristóbal Ecatepec. After his death, his second in command, Vicente Guerrero, continued the war of independence. He remained the only major rebel leader still at large, keeping the rebellion going through an extensive campaign of guerrilla warfare.

In 1820 Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent an army under the leadership of General Agustín de Iturbide against the troops of Guerrero. Iturbide had a meeting with Guerrero and as a result they joined forces against Spain. On the 21st September 1821, the combined armies marched into Mexico City. Seven days later, representatives of the Spanish government and Iturbide signed the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire. As a result of this document, Alta California came under the control of Mexico.

In 1822, William Richardson arrived in Yerba Buena on a British whaling ship, L'Orient. There had been a dispute on board ship and he petitioned the Spanish governor for permission to remain in Alta California. He agreed as long as he promised to teach the local people at Mission San Francisco de Asís how to construct small boats for use in the bay. Richardson, who was fluent in Spanish, became the first non-Spanish European to settle in the area.

One of his first projects was the construction of a small boat which he used to move people and cargo around the bay. In 1823 Richardson converted to Catholicism, became a naturalized citizen of Mexico, and changed his name to Guillermo Antonio Richardson. Two years later he married Maria Antonia Martinez (1803–1887), the daughter of Ygnacio Martinez, commandant of the Presidio of Yerba Buena. Richardson now became involved in in the expanding California coastal trade.

In August 1826, Jedediah Smith, a mountain man, and a 15 men team headed for the Wasatch Mountains. After crossing the Colorado River the men entered the Black Mountains of Arizona. Smith was unable to find "beaver water" and instead of retracing his steps decided to cross the Mojave Desert in California. Smith wrote about this adventure in his journal: "I have at different times suffered the extremes of hunger and thirst. Hard as it is to bear for successive days the knawings of hunger, yet it is light in comparison to the agony of burning thirst and, on the other hand, I have observed that a man reduced by hunger is some days in recovering his strength. A man equally reduced by thirst seems renovated almost instantaneously. Hunger can be endured more than twice as long as thirst. To some it may appear surprising that a man who has been for several days without eating has a most incessant desire to drink, and although he can drink but little at a time, yet he wants it much oftener than in ordinary circumstances."

It took Smith and his party 15 days to cross this flat, salt-crusted plain under a blazing sun. Eventually they arrived at what is now Los Angeles. As Kevin Starr has pointed out that "the Smith party constituted the first American penetration of California overland from the east." This area was under the control of Mexico and Smith and his party were arrested and kept at San Diego until January, 1827. The group then wintered in the San Joaquin Valley.

In May 1827, Smith took his men across the Sierra Nevada mountains. The deep snow halted the first attempt and when he tried for a second time, Smith only had two companions. This time he managed to cross the mountains through what is now known as Ebbetts Pass. The three men therefore became the first white men to achieve this feat.

The desert east of the Sierra caused Smith and his companions serious problems. On 24th June Smith wrote in his diary: "With our best exertion we pushed forward, walking as we had been for a long time, over the soft sand. That kind of traveling is very tiresome to men in good health who can eat when and what they choose, and drink as often as they desire, and to us, worn down with hunger and fatigue and burning with thirst increased by the blazing sands, it was almost insupportable." On 25th June one of the men, Robert Evans, did not have the strength to continue. Smith and the other man went on ahead. Smith wrote in his diary: "We left him and proceeded onward in the hope of finding water in time to return with some in season to save his life. After traveling about three miles we came to the foot of the mountain and there, to our inexpressible joy, we found water."

The three men eventually reached Bear Lake. Smith now wrote to William Clark about his trip and what he had discovered. In his letter he explained how he had discovered "a country which has been, measurably, veiled in obscurity, and unknown to the citizens of the United States." On 13th June Smith assembled a new party of 18 men and two women to go back to California. He decided to use the same route as before. While crossing the Colorado River the party was attacked by members of the Mojave tribe. Ten of the men were killed and the two women were captured. Smith and the seven remaining men reached California in late August. Once again Smith was arrested by the Mexican authorities. He was eventually released after he promised he would leave California and not return.

Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has argued: "Smith's heroic journey - the double encirclement of the Far West - was the physical, moral, and geopolitical equivalent of the great voyages of exploration off the California coast in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The Spaniards linked California to the sea; Smith linked California to the interior of the North American continent."

Monterey was the main port of entry for Spanish ships. In 1835 Governor José Figueroa made Yerba Buena, an alternative port and invited Richardson to assume the position of Port Captain. He also started a profitable shipping company and ran the sole ferry company across the Bay. Richardson also laid out the street plan for the settlement of Yerba Buena. Later he moved his family to the 19,751 acre farm that became known as Rancho Saucelito. The local harbour became known as Richardson's Bay, and most of the ships entering Yerba Buena Cove, obtained their water and supplies there.

During this period mountain men such as Jedediah Smith, Tom Fitzpatrick, Hugh Glass, Jim Beckwourth, David Jackson, William Sublette and James Bridger began making overland trips to California. In 1833 Captain Benjamin Bonneville suggested to Joseph Walker that he should take a party of men to California. The beaver appeared to be decline in the Rocky Mountains and it was thought that new trapping opportunities would be found in this unexplored territory. Walker and his party of forty men were the first Americans to explore the Yosemite Valley.

In 1839 John Sutter moved to Yerba Buena. The following year Sutter established the colony of Nueva Helvetia (New Switzerland), which became a centre for trappers, traders and settlers in the region. The venture was a great success and within a couple of years Sutter was a wealthy businessman. Sutter had tremendous power over the area and admitted: "I was everything, patriarch, priest, father and judge." He also purchased 49,000 acres at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento rivers. This site dominated three important routes: the inland waterways from San Francisco, the trail to California across the Sierra Nevada and the Oregon-California road.

During this period John Marsh acquired the Rancho Los Meganos at the foot of Mount Diablo in the San Joaquin Valley, east of San Francisco Bay. His 50,000 acre ranch contained thousands of cattle and horses. Marsh realised that he could make a great deal of money if he could persuade people to travel overland from Missouri to California. Along with John Sutter he publicised California as a land of opportunity. Frank McLynn has argued that "Sutter and Marsh underwrote the golden legend of California as the Promised Land."

After reading read a book by Antoine Robidoux, a farmer John Bidwell, from Platte County, began to considering the prospect of emigrating to California. As Bidwell explained at the time: "his description of the country made it seem like paradise". Bidwell established the Western Emigration Society and published news that he intended to take a large wagon train to California. The idea was very popular and soon the society had the names of 500 people who wanted to take part in this momentous event.

Missouri shopkeepers, fearing a rapid decline in customers, decided to mount a campaign against the idea. Local newspapers published stories about the dangers of travelling overland to California. Also, a great deal of publicity was given to Travels in the Great Western Prairies, a book by Thomas Farnham. In the book Farnham described in detail the hardships people would face on the journey. As a result of this campaign only about a hundred people turned up to leave Sapling Grove on 9th May, 1841. This was to be the first ever wagon train taking people from the Missouri River to California. The Bidwell expedition included only five women.