Cahuilla

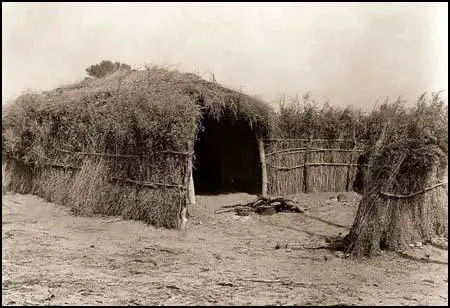

The Cahuilla lived between the San Bernardino Mountains and the Salton Sea in the Imperial Valley in Southern California, and close to the Mojave Desert. It has been estimated that in the 18th century there were about 2,500 Cahuilla living in California. According to Evelyn Wolfson, "they built long, narrow dome-shaped houses with straight sides covered with brush". The men hunted elk and deer in the mountains and trapped rabbits and other small animals in the foothills.

David Prescott Barrows studied the ethnobotany of the Cahuilla Indians and recorded 60 plants they used for food and 28 for medicines. In his thesis, The Ethno-Botany of the Cohuilla Indians (1900) he argued: "A review of the food supply of these Indian forces in upon us some general reflections and conclusions. First, it seems certain that the diet was a much more diversified one than fell to the lot of most North American Indians. Roaming from the desert, through the mountains to the coast plains, they drew upon three quite dissimilar botanical zones... And yet this habitat, dreary and forbidding as it seems to most, is after all a generous one. Nature did not pour out her gifts lavishly here, but the patient toiler and wise seeker she rewarded well. The main staples of diet were, indeed, furnished in most lavish abundance."

Women and children collected large crops of acorns each year. According to the authors of The Natural World of the California Indians (1980): "The total annual acorn crop for Central California would have run into the millions of tons, but only a small fraction of the yield was gathered each year by the Indians. The bearing season for oaks is only a few weeks, and Indians were not the only collector of acorns. Squirrels, insects, woodpeckers, and bears competed with the Indians for the acorn crop." John C. Frémont saw an Indian village where near to each house was "a crate formed of interlaced branches and grass, in size and shape like a very large hogshead. Each of these contained from six to nine bushels of acorns."

All acorns produced by California oaks contain tannin, which is very bitter. The Indians dealt with this problem by removing the acorn hull and to grind the interior into a flour in a stone mortar or on a flat grinding slab. They then constantly poured warm water over the flour to leach out the tannin. The leached flour was then mixed with water in a watertight basket and boiled by dropping hot stones into the gruel. The cooked mush was then either drunk or eaten with a spoon. Sometimes it was baked into a cake.

Males tended to wear buckskin breechcloths whereas women favoured buckskin aprons. They covered their feet with pieces of leather, which they strapped on with buckskin thongs. The Cahuilla spoke takic, a language they shared with their Gabrielino neighbours.

Robert F. Heizer has argued that the Cahuilla made "good-quality pottery, in gray, brown, or red. Some pieces recovered from archaeological sites are decorated with black lines." However, like most tribes in California, they mainly used baskets for collecting acorns or buckeye nuts.

In 1774 Juan Bautista de Anza made contact with the Cahuilla when he was searching for a trade route between Sonora and Monterey in Alta California. As the Cahuilla were an interior tribe and therefore had little contact with the Spanish settlers. They found it difficult to avoid Americans who travelled from the east to California after the 1848 Gold Rush. As a result they died in large numbers from smallpox and other epidemics. They also suffered when the settlers diverted their streams and took away their water.

The survivors went to live on the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation in the Palm Springs area. A 1990 census revealed a Cahuilla population of 800. Only 35 could still speak in their original language. It is therefore nearly extinct, as most speakers are middle-aged or older.

Primary Sources

(1) David Prescott Barrows, The Ethno-Botany of the Cohuilla Indians (1900)

A review of the food supply of these Indian forces in upon us some general reflections and conclusions. First, it seems certain that the diet was a much more diversified one than fell to the lot of most North American Indians. Roaming from the desert, through the mountains to the coast plains, they drew upon three quite dissimilar botanical zones... And yet this habitat, dreary and forbidding as it seems to most, is after all a generous one. Nature did not pour out her gifts lavishly here, but the patient toiler and wise seeker she rewarded well. The main staples of diet were, indeed, furnished in most lavish abundance.