John Marsh

John Marsh was born in Danvers, Massachusetts, in 1799. After graduating from Phillips Academy in Andover he attended Harvard University from 1819 to 1823. He also studied medicine with a Boston doctor.

Marsh moved to Minnesota where he opened a school. Later he became an Indian Agent for the Sioux Agency. He moved to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin and during the Black Hawk War was blamed for a massacre of the Fox and Sauk by the Sioux. After being discovered selling guns illegally to Native Americans he was forced to move to Independence, Missouri, where he became a merchant.

He moved to Sante Fe where he was employed by the American Fur Company. In 1836 he arrived in Los Angeles where he established himself as a doctor. According to the author of Wagons West: The Epic Story of America's Overland Trails (2002): "On the basis of a BA diploma written in Latin from Harvard - scarcely more than a certificate of attendance - he professed himself a physician, set up practice and even performed operations successfully, accepting hides and tallow as payment." Marsh therefore became the first practicing physician on the Pacific Coast.

Kathleen Mero has argued: "He was an educated man from a blueblood family, the last person you'd expect to be dealing with all the rough and tumble of ... the frontier," Mero said in an interview. "He was hungry for the wilderness, never satisfied, always kept going west."

In 1838 he acquired the Rancho Los Meganos at the foot of Mount Diablo in the San Joaquin Valley, east of San Francisco Bay. His 50,000 acre ranch contained thousands of cattle and horses. Marsh realised that he could make a great deal of money if he could persuade people to travel overland from Missouri to California. Along with John Sutter he publicised California as a land of opportunity. Frank McLynn has argued that "Sutter and Marsh underwrote the golden legend of California as the Promised Land."

Of the 4th November, 1841, John Bidwell and his party arrived at Marsh's Fort. They were the survivors of the first wagon train to attempt the overland journey from Missouri. Cheyenne Dawson wrote: "We had expected to find civilization, with big fields, fine houses, churches, schools, etc. Instead, we found houses resembling unburnt brick kilns, with no floors, no chimneys, and with the openings for doors and windows closed by shutters instead of glass."

Marsh provided them with pork and beef tortillas. When he gave them with a bill for five dollars each next morning they decided they could not afford another night of Marsh's hospitality and left the fort in search of work. Bidwell estimated that there was only about one hundred white natives of the United States in California in 1841.

Rancho Los Meganos was attacked by band of outlaws led by Claudio Feliz on 5th December, 1850. They overran the rancho, captured Marsh, looted the adobe ranch house, and killed a visitor, William Harrington. The bandits escaped with $300, gold watches and guns.

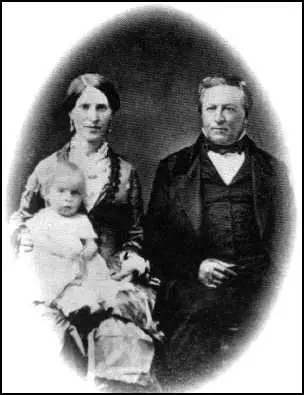

In 1851 Marsh met Abigail Tuck. She wrote to her parents: "The bachelor has been out here sixteen years. He is about fifty years old and is a graduate of Cambridge College. I like his appearance and have since become further acquainted with him." The couple married and Abigail told her mother that she now had "some one to love and care for me and who has enough of this material goods to satisfy every reasonable want. I expect to spend my days here...Next year he intends to build a house. There is a house here, but not one that he wants me to live in."

In March 1852, Abigail gave birth to a girl named Alice: "She seldom cries and is the best child I ever saw. Her teeth are now beginning to trouble her, what a treasure to us she is. She has dark blue eyes and very light hair nearly white...The Indians who live on our rancho almost worship her - they think she is a perfect little beauty."

During the Californian Gold Rush Marsh had problems with squatters. Marsh attempted to organize vigilantes against squatters, Gilbert Leonard and John Osborne. Marsh was arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit assault and battery. He was convicted and fined $500.

A developed tuberculosis and on 12th June 1855 she wrote to her parents: "As I expect to be but a few more days to spend in this world I must say farewell! But do not weep or mourn for me. You know the source from whence to draw consolation. In a few more months or years I expect to meet you in another & better world where the wicked cease from troubling & the weary can rest. I did hope to see you again in this world, but God has ordered it otherwise. He calls and I must go. I have no wish to be here longer, but have rather depart & be with my Savior."

Abigal died in August. John Marsh wrote to her parents that: "During the long & painful sickness of my dear wife I have continually kept you advised of her condition & I have now to communicate the sad news of her decease. She died last Saturday morning at 5 o'clock.... At present I am so overwhelmed with sorrow that I hardly know what to think or determine, but it is probable that within the next six months I shall visit Massachusetts the place of my birth, & bring my little girl to see her grandparents."

On 24th September 1856, John Marsh travelled to San Francisco. On the road between Pacheco and Martinez, at Pacheco, he was ambushed and murdered by three of his employees over a dispute over their wages. Two of Marsh's killers were tracked down and brought to trial ten years after the murder. The third was never caught. One killer turned state evidence and was freed after the trial. The other served 25 years in San Quentin for second-degree murder.

Primary Sources

(1) Abigail Tuck Marsh, letter to her parents (14th July, 1851)

I concluded (sic) to stop a few weeks with Mrs. Appleton a lady with whom I used to board with. She promised to take me on a pleasure trip over the mountains into the San Joaquin Valley. This trip promised to be quite an interesting one. The first day we came about twenty five miles. The next morning we started early & wandered among the mountains. When about one o'clock we came to the place where we started from in the morning, then we took a guide who directed us over the mountains. About sunset we came to a bachelor's rancho, but no one was at home. We had seven or eight miles further to go but did not know which way it was.... We later returned to the bachelor and found him at home and glad to see us. He was an acquaintance of Mrs. Appleton's. We stayed with him all night and the next morning completed our journey.

The bachelor has been out here sixteen years. He is about fifty years old and is a graduate of Cambridge College. I like his appearance and have since become further acquainted with him. His name is Doctor John Marsh & he is now your brother-in-law. We were married on the 24 of June. Our acquaintance was short only a little more than two weeks but I had [no] risk to [run] and is worthy in every respect, [engaging] my affections. I feel that my roaming is at an end - I have some one to love and care for me and who has enough of this material goods to satisfy every reasonable want. I expect to spend my days here...

Next year he intends to build a house. There is a house here, but not one that he wants me to live in. I know you will all be rejoiced to hear that I am married. Well, I think I have waited long enough, and I feel that I am compensated for so doing. He says he hopes he is a Christian & that is all I can find out. Pray for us that we be bright and shining lights in the world. My religious privileges may be small. The Doctor says he will go with me whenever I want to go to San Francisco.

I would like to come home next year, but have faint hopes, only as I know it will be very difficult for us to leave. Please do write often and do not forget us.

(2) Abigail Tuck Marsh, letter to her parents (29th August, 1852)

My time is mostly spent in superintending my domestic affairs. Since I last wrote you we have had a California specimen favorable to everyone since we last wrote you & is acknowledged by all to be one of the rarest specimen of the country and her father thinks one of the rarest in the market. We call her Alice Francis. She is more than five months old...

How I wish you could see our darling little Alice. She seldom cries and is the best child I ever saw. Her teeth are now beginning to trouble her, what a treasure to us she is. She has dark blue eyes and very light hair nearly white...The Indians who live on our rancho almost worship her - they think she is a perfect little beauty...Some of them have lived with the Doctor from his first arriving into the country...I often go see them and carry them medicine when they are sick, they now have the chills and fever [ ] great many of them and would die if left to themselves.

(3) Abigail Tuck Marsh, letter to her parents (29th August, 1852)

You want to know how we find our cattle, when we want to drive them all together which is called a roundup, some eight or ten men go in different directions and drive to a particular place, when the cattle get there they stop. This is called the rodeo ground which the cattle all know as well as we do. Then if we want to sell any we point out those we want to sell and drive them off. Our cattle are all marked in the ears and branded on the hips so that we know ours from other peoples and every owner has his brand and mark. So that if our cattle get on to other people's crops or farms we go and drive them home and other people do the same. They mark these once a year on every rancho.

Sometimes people steal our cattle for which a great many have been hung. Little more than two years or so, four men were hung for stealing the Doctor's and another man's cattle. We have now less stolen every year. We sold a hundred steers not long since for five thousand dollars. This is a very easy way to get money.

(4) Abigail Tuck Marsh, letter to her parents (5th October, 1854)

The Doctor has gone to Martinez and San Francisco. At Martinez it is court week and he had to go as a witness, in the trial of three murderers, who killed a man about two miles from our house...they shot him it was just dark and he escaped to our house and lived two days and nights...They are all convicted of murder in the first degree, and will be hung, we suppose. They are all very young men from 18 to 25, but they have bad countenances...

We have a great deal of money in a year but it goes to hire helpers, protect us from thieves and vagabonds that surround us, but we hope to have better times before long.

(5) Abigail Tuck Marsh, letter to her parents (12th June, 1855)

As I expect to be but a few more days to spend in this world I must say farewell! But do not weep or mourn for me. You know the source from whence to draw consolation - In a few more months or years I expect to meet you in another & better world where the wicked cease from troubling & the weary can rest. I did hope to see you again in this world, but God has ordered it otherwise. He calls and I must go. I have no wish to be here longer, but have rather depart & be with my Savior. Oh that I could have you here with me that I could have your prayers & your sympathies that are so much needed. May God bless you my Parents & support & comfort you.

(6) John Marsh, letter to his wife's parents (18th August, 1855)

During the long & painful sickness of my dear wife I have continually kept you advised of her condition & I have now to communicate the sad news of her decease. She died last Saturday morning at 5 o'clock. Perfectly calm and resigned and even desirous to depart & with her Savior. I have been so oppressed with grief that I have not been able to send you the sad intelligence until today & now I can hardly tranquilize myself sufficiently to write.

Yes, my dear Sir your affectionate & and most excellent daughter has departed from the earth to that eternal home where sorrow & sickness are unknown. I have lost the most loving, affectionate & dutiful of wives, & my child the kindest and best of mothers.

Last Sabbath evening the remains were deposited in a place long ago selected by herself in the orchard near the house. The funeral was attended by a minister & a large concourse of friends & neighbors. She was repeatedly visited and consoled by the Rev. Mr. Brierly and other clergymen. She has for a long time been attended by Mrs. Osgood a member of the Baptist church & a kind & excellent nurse, & and(sic) by Mrs. Thomson her neighbor & particular friend.

Some months ago she said to me that probably after her death her relatives might desire her body to be sent to the east. I informed her that whatever was her wish it should be complied with - Her reply was that she had no other wish "but to lie by my side of her husband," and whenever it shall please God to my spirit hence it is my intention to have [my] bones laid by her side.

Your little granddaughter is in good health & is for the present with Mrs. Thomson by the special desires of the mother.

A portion of her clothes she desired to be sent to her mother & sisters, & they will be accordingly forwarded in due time.

At present I am so overwhelmed with sorrow that I hardly know what to think or determine, but it is probable that within the next six months I shall visit Massachusetts the place of my birth, & bring my little girl to see her grandparents.

(7) Cecilia Rasmusse, Los Angeles Times (6th February, 2006)

John Marsh was one of those Yankee chameleons who made the years before California statehood so interesting for historians -- and so profitable for himself.

His adherents and critics have staked many a claim: that he was the first to compile a Sioux dictionary; that he was the first Harvard man in the Far West; that his glowing letters about California brought the first wagon train of settlers here long before the Gold Rush; and that he was, if only for a year, the first Yankee-trained physician in Los Angeles.

Marsh inspired a 1930 biography by George D. Lyman and piqued the interest of modern historian Kathleen Mero, who works for the John Marsh Historic Trust in Contra Costa County in Northern California.

"He was an educated man from a blueblood family, the last person you'd expect to be dealing with all the rough and tumble of ... the frontier," Mero said in an interview. "He was hungry for the wilderness, never satisfied, always kept going west."

Until he got to Mexican-governed California. "I have at last found the Far West and intend to end my ramblings here," he wrote to friends back East.

Some Contra Costa County residents want to turn Marsh's mansion into a history center or the centerpiece of a proposed state park dedicated to California pioneers. The 3,600-acre site, owned by the state, is all that remains of his 50,000-acre holdings.

Born in Danvers, Mass., in 1799, Marsh earned a degree from Harvard in general education and worked as a teacher. For a while, he was an assistant Indian agent for the Winnebago near the Illinois-Wisconsin border, Mero says.

In 1826, Marguerite Deconteaux, a woman of French Canadian and Sioux descent, bore him a son. Charles had two webbed toes, a genetic characteristic in the Marsh family.

Around that time, Marsh got to know Abraham Lincoln in New Salem, Ill. The future president carved a pocketknife for Marsh's son, Mero says.

Sometime between 1828 and 1832, Marsh informally studied medicine for two years under an Army physician in Wisconsin. But after Deconteaux died in 1831, a heartbroken Marsh left the area, Mero says. In his biography, "John Marsh, Pioneer," Lyman had attributed the move to bad debts and accusations of gun-running.

"Lyman did not do a good job summing up Marsh's personality," Mero says. "He ... repeats claims from the journals of others without really looking into it. But of course, he didn't have the databases we have today."