Eugen Boissevain

Eugen Boissevain, the son of Charles Boissevain (1842-1927) and Emily Héloïse MacDonnell (1844-1931), was born in Amsterdam on 20th May 1880. Boissevain made his fortune by importing coffee beans from Java. He developed a reputation as a hedonist. Floyd Dell described him as "an adventurous man of business, was in private life a playboy with incredible energy, romantic zest, and imagination."

A friend, Alyse Powers, argued that Boissevain was "handsome, reckless, mettlesome as a stallion breathing the first morning air, he would laugh at himself, indeed laugh at everything, with a laugh that scattered melancholy as the wind scatters the petals of the fading poppy...He had the gift of the aristocrat and could adapt himself to all circumstances... his blood was testy, adventurous, quixotic, and he faced life as an eagle faces its flight."

Boissevain was introduced to Inez Milholland by Max Eastman. A leading figure in the women's suffrage movement, was associated with a group of socialists involved in the production of The Masses journal. This included John Reed, Floyd Dell, Crystal Eastman, Louis Untermeyer, William Walling, Art Young, Michael Gold, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Randolph Bourne, Dorothy Day, Mabel Dodge, Mary Heaton Vorse and Louise Bryant. The couple were married in July 1913.

Inez Milholland was a strong opponent of the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in the fact that the articles and cartoons that appeared in journal attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict. In December, 1915, Milholland and other pacifists travelled on Henry Ford's Peace Ship to Europe.

On her return to the United States she became one of the leaders of the National Women's Party. The movement's most popular orator, Milholland was in demand as a speaker at public meetings all over the country. Milholland, who suffered from pernicious anemia, and was warned by her doctor of the dangers of vigorous campaigning. However, she refused to heed this advice and on 22nd October, 1916, she collapsed in the middle of a speech in Los Angeles. She was rushed to hospital but despite repeated blood transfusions she died on 25th November, 1916.

Boissevain remained in Greenwich Village and his friend, Floyd Dell recalls how he was attending a party at the home of Dudley Field Malone and Doris Stevens, when he met Edna St Vincent Millay: "We were all playing charades at Dudley Malone's and Doris Stevens's house. Edna Millay was just back from a year in Europe. Eugene and Edna had the part of two lovers in a delicious farcical invention, at once Rabelaisian and romantic. They acted their parts wonderfully-so remarkably, indeed, that it was apparent to us all that it wasn't just acting. We were having the unusual privilege of seeing a man and a girl fall in love with each other violently and in public, and telling each other so, and doing it very beautifully."

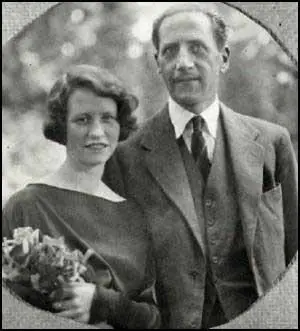

The couple married in 1923. They lived at a farmhouse they named Steepletop, near Austerlitz. Both were believers in free-love and it was agreed they should have an open marriage. Boissevain managed Millay's literary career and this included the highly popular readings of her work. In his autobiography, Homecoming (1933), Floyd Dell commented that he had "never heard poetry read so beautifully".

In 1931 Edna St Vincent Millay published, Fatal Interview (1931) a volume of 52 sonnets in celebration of a recent love affair. Edmund Wilson claimed the book contained some of the greatest poems of the 20th century. Others were more critical preferring the more political material that had appeared in The Buck and the Snow.

Eugen Boissevain died in Boston on 29th August, 1949 of lung cancer. Edna St Vincent Millay was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in Steepletop on 19th October 1950.

Primary Sources

(1) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

During these Greenwich Village days I took Edna and Norma Millay to call on Eugene Boissevain and Max Eastman; it was for some reason a stiff, dull evening; everybody was bored. I was annoyed with the girls and disgusted with our-boorish hosts; it was impossible to guess that Edna Millay and Eugene Boissevain would one day be married to one another; they were certainly not in the least interested in one another that evening!....To conclude the story, I was present at their second meeting, some years later, in Croton-on-Hudson. We were all playing charades at Dudley Malone's and Doris Stevens's house. Edna Millay was just back from a year in Europe. Eugene and Edna had the part of two lovers in a delicious farcical invention, at once Rabelaisian and romantic. They acted their parts wonderfully-so remarkably, indeed, that it was apparent to us all that it wasn't just acting. We were having the unusual privilege of seeing a man and a girl fall in love with each other violently and in public, and telling each other so, and doing it very beautifully.

The aftermath was equally romantic. Edna Millay's health had broken down in Europe, and she was really a very sick girl when she came out to the country for a week-end. The next day she was all in; Eugene took her to his home, called the doctor, and nursed her like a mother. His care at this time perhaps saved her life, for her condition, as shown by a subsequent operation, was very serious. When she was well enough they were married.

Eugene Boissevain had been the husband of Inez Milholland, Edna Millay's heroine of college days. He himself, an adventurous man of business, was in private life a playboy with incredible energy, romantic zest, and imagination. Moreover, he had really enjoyed being the husband of a gallant Feminist leader; his pride hadn't been hurt by her dedication to a cause, and her not remembering to darn his socks. A divinely ordained husband, it would seem, for a girl poet, who would certainly not remember to darn his socks, either!