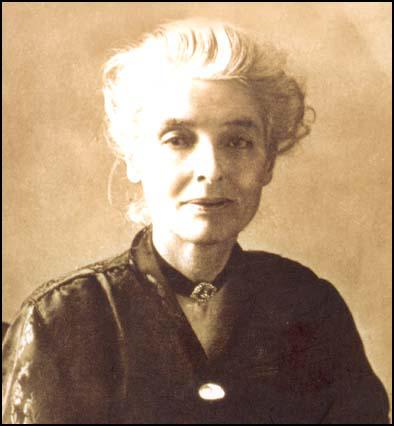

Beatrice Webb

Beatrice Potter, the eighth daughter of Richard Potter and Laurencina Heyworth, was born on 2nd January, 1858, at Standish House in Gloucestershire. Her grandfather was Richard Potter, the Radical MP for Wigan.

Her father was a wealthy railway entrepreneur and although Beatrice travelled widely with her parents, she received little formal education. However, Beatrice was an intelligent child and read books on philosophy, science and mathematics. She was very impressed by the work of Herbert Spencer and Auguste Comte and came to the conclusion that "self-sacrifice for the good of the community was the greatest of all human characteristics".

In 1883 Potter joined the Charity Organization Society (COS), an organisation that attempted to provide Christian help to those living in poverty. While working with the poor, Beatrice Potter realised that charity would not solve their problems. She began to argue that it was the causes of poverty that needed to be tackled, such as the low standards of education, housing and public health.

In 1882 Beatrice fell in love with one of Britain's leading politicians, Joseph Chamberlain. The relationship ended unhappily and in 1886 Beatrice went to work as a researcher for Charles Booth, who was involved in studying the lives of working people living in London. Beatrice was assigned to study and investigate the lives of the dock workers in the East End. Other topics covered by Beatrice included Jewish immigration and sweated labour in the tailoring trade. Her articles on dock workers and the sweating trades were published in the journal, the Nineteenth Century and as a result was invited to testify before the House of Lords on the subject.

At the time she had fairly conservative opinions about the role of women. In 1886 she wrote about her impressions of Annie Besant: "I felt interested in that powerful woman, with her blighted wifehood and motherhood and her thirst for power and defence of the world. I heard her speak, the only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion. But to see her speaking made me shudder. it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world."

While working in Lancashire Beatrice Potter became interested in the good work achieved by the different co-operative societies that existed in most of Britain's industrial towns. She began involved in writing a book on the subject (The Co-operative Movement) and was advised to contacted Sidney Webb, who had also researched this aspect of working-class life. Her initial reaction was not very positive. She wrote in her diary: "his tiny tadpole body, unhealthy skin, cockney pronunciation, poverty, are all against him". They eventually became close friends and in 1892 she agreed to marry him. She wrote in her diary that "it is only the head that I am marrying." Beatrice had an income of £1,000 that she had inherited from her rich father. This money enabled Sidney to give up his post as a Civil Servant and he now concentrated on his political work.

Sidney Webb was at this time a leading figure in the Fabian Society. The society believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. The members, who included Edward Carpenter, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, and George Bernard Shaw agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". Beatrice also shared these views and also joined the group.

Beatrice and Sidney Webb worked on several books together including The History of Trade Unionism (1894) and Industrial Democracy (1897). The research that they carried out while writing these books convinced them there was a need to establish a new political party that was committed to obtaining socialism through parliamentary elections.

In 1894 Henry Hutchinson, a wealthy solicitor from Derby, left the Fabian Society £10,000. Beatrice and Sidney Webb suggested that the money should be used to develop a new university in London. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) was founded in 1895. As Sidney Webb pointed out, the intention of the institution was to "teach political economy on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto, and to serve at the same time as a school of higher commercial education".

The Webbs first approached Graham Wallas, a leading member of the Fabian Society, to become the Director of the LSE. Wallas declined the offer and W. A. S. Hewins, a young economist at Pembroke College, Oxford, was appointed instead. With the support of the London County Council (LCC) and the Technical Education Board, the LSE flourished as a centre of learning.

In 1898 the Webbs went on a year long research trip to North America, Australia and New Zealand. The Webbs main concern was to discover different approaches to local government. When they arrived home they carried out a study of the organization and function of English local government. Published in eleven volumes over a twenty-three year period, English Local Government, became the standard work on the subject. Beatrice wrote in her diary: "Are the books we have written together worth (to the community) the babies we might have had?"

On 27th February 1900, the Fabian Society joined with the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and trade union leaders to form the Labour Representation Committee (LRC). The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons.

Beatrice Webb was willing to work with any political party in order to obtain the policies she believed in. When the Conservative Party won the 1900 General Election, the Webbs drafted what later became the 1902 Education Act. The Webbs were strong critics of the Poor Law system in Britain. In 1905 the government established a Royal Commission to look into "the working of the laws relating to the relief of poor persons in the United Kingdom". Beatrice Webb was asked to serve as a member of the commission and her husband assisted with collecting the data on how the system was working. Beatrice disagreed with most of the members on the Royal Commission and together with Sidney Webb wrote and published a Minority Report. In their report the Webbs called for: (1) the end of the Poor Law; (2) the establishment and coordination of employment bureau throughout Britain to make efficient use of the nation's labour resources; (3) improving essential services such as education and health. The Liberal government headed by Herbert Asquith accepted the Majority Report and rejected the advice given by the Webbs.

In 1913 Beatrice Webb helped create the Fabian Research Department. During the same year the Webbs started a new political weekly, The New Statesman. Edited by Clifford Sharp with contributions from the Webbs, as well as from other members of the Fabian Society such as George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes and G. G. H. Cole, the journal promoted socialist reform of society.

During the First World War Beatrice Webb served on several government committees. She also wrote several Fabian Society pamphlets such as Labour and the New Social Order (1918), The Wages of Men and Women - Should They be Equal? (1919), Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain (1920) and the Decay of Capitalist Civilization (1923).

In the 1923 General Election Beatrice's husband, Sidney Webb, was chosen to represent the Labour Party in the Seaham constituency. Webb won the seat and when Ramsay MacDonald became Britain's first Labour Prime Minister in 1924, he appointed Webb as his President of the Board of Trade.

Webb left the House of Commons in 1929 when he was granted the title Baron Passfield. Now in the House of Lords, Webb served as Secretary of State for the Colonies in MacDonald's second Labour Government. However, on a point of principle, Beatrice refused to accept the title of Lady Passfield.

In 1932 the Webbs visited the Soviet Union. Although unhappy with the lack of political freedom in the country they were impressed with the rapid improvement in the health and educational services and the changes that had taken place to ensure economic and political equality for women. When they returned to Britain they wrote a book on the economic experiments taking place in the Soviet Union called Soviet Communism: A New Civilization? (1935). In the book the Webbs predicted that "the social and economic system of planned production for community consumption" of the Soviet Union would eventually spread to the rest of the world. They added that they hoped this would happen through reform rather than revolution.

Despite the Stalinist purges and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Webbs continued to support the Soviet economic experiment and in 1942 published The Truth About Soviet Russia (1942).

Beatrice Webb died on 30th April, 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Beatrice Potter attended the first meeting of Charles Booth's Board of Statistical Research on 17th April, 1886.

Charles Booth's first meeting of the Board of Statistical Research at his London office. Object of the Committee is to get a fair picture of the whole of London society - the 4,000,000 - by district and employment, the two methods to be based on census returns. At present Charles Booth is the sole worker in this gigantic undertaking. I intend to do a little bit of it while I am in London, not only to keep the Society alive, but to keep me in touch with actual facts so as to limit my study of the past to that part of it useful in the understanding of the present.

(2) The Pall Mall Gazette described Beatrice Potter giving evidence to the House of Lords on the subject on sweated labour.

Miss Potter, dressed in black and wearing a very dainty bonnet, tall, supple, dark, with bright eyes, and quite cool in the witness chair, who was fluent on coats and eloquent on breeches. Unfortunately, though her voice was a little shrill, it was very difficult to hear sentences, which were very sharply delivered.

(3) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (27th November, 1886)

I am sorry I have not seen Mrs Besant again. We met and I felt interested in that powerful woman, with her blighted wifehood and motherhood and her thirst for power and defence of the world. I heard her speak, the only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion. But to see her speaking made me shudder. it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world.

(4) In her diary Beatrice Potter described studying at the British Museum (16th November, 1888)

A long morning at the British Museum reading up Jewish Chronicle and suchlike. The Reading Room has a homely feeling; it was there in the spring of 1885 that I first recovered my thirst for knowledge and again felt the passion for truth overcoming all other feeling. There you see decrepit men, despised foreigners, forlorn widows and soured maids, all knit together by a feeling of fellowship with the great immortals.

(5) In her diary Beatrice Potter welcomed the London Dock Strike (29th August, 1889)

The dock strike becoming more and more exciting - even watched at a distance. Originally 500 casuals marched out of the West and East India Docks - in another day the strike spread to the neighbouring docks - in a week half East London was out. For the first time a general strike of labour, not on account of the vast majority of strikers, but to enforce the claims to a decent livelihood of some 3,000 men. The hero of the scene, John Burns the socialist, who seems for the time to have the East London working men at his feet, with Ben Tillett as his lieutenant and ostensible representative of the dockers.

The strike is intensely interesting to me personally, as proving or disproving, in any case modifying, my generalization on 'Dock Life'. Certainly the solidarity of labour at the East end is a new thought to me - the dock labourers have not yet proved themselves capable of permanent organization but they have shown the capacity for common action. And what is more important, an extraordinary manifestation of practical sympathy, of effectual help, has been evoked among all classes in East London, skilled artisans making common cause with casuals, publicans, pawnbrokers and tradesmen supporting them.

(6) Beatrice Potter recorded in her diary her first meeting with Sidney Webb (14th February, 1890)

Sidney Webb, the socialist, dined here to meet Charles and Mary Booth. A remarkable little man with a huge head on a very tiny body, a breadth of forehead quite sufficient to account for the encyclopaedic character of his knowledge, a Jewish nose, prominent eyes and mouth, black hair, somewhat unkept, spectacles and a most bourgeois black coat shiny with wear.

With his thumbs fixed pugnaciously in a far from immaculate waistcoat, with his bulky head thrown back and his little body forward he struts even when he stands, delivering himself with extraordinary rapidity of thought and utterance and with an expression of inexhaustible self-complacency. But I like the man. There is a directness of speech, an open-mindedness, an imaginative warm-heartedness which should carry him far. He has the self-complacency of one who is always thinking faster than his neighbours, who is untroubled by doubts, and to whom the acquisition of facts is as easy as the grasping of matter; but he has no vanity and is totally unself-conscious.

(7) By February 1890, Beatrice Potter considered herself to be a socialist. She recorded in her diary what she meant by socialism (15th February, 1890)

I have become a socialist not because I believe it would ameliorate the conditions of the masses (though I think it would do so) but because I believe that only under communal ownership of the means of production can you arrive at the most perfect form of individual development, at the greatest stimulus of individual effort; in other words complete socialism is only consistent with absolute individualism. As such, some day, I shall stand on a barrel and preach it.