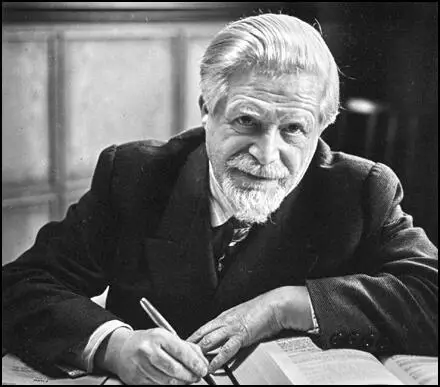

Sydney Silverman

Sydney Silverman, the son of a draper, was born in Liverpool on 8th October 1895. The family were very poor and two of the four children died before reaching adulthood. According to his biographer, Sarah McCabe: "The Silvermans were poor, but their poverty was not that of nineteenth-century industrial labour, for Myer Silverman was a pedlar or, more properly, a chapman, who lived as a small-time entrepreneur among his labouring fellows. He was never materially successful, probably because his sympathy for his impoverished customers did not allow him to enrich himself at their expense."

Silverman was extremely intelligent and obtained a scholarship to the Liverpool Institute, a leading grammar school in the city. This was followed by two further scholarships, one to the University of Liverpool and the other to Oxford University. However, he could not afford the expense of an Oxford scholarship and decided to take up the Liverpool offer and began his studies in English literature.

First World War

In 1916 the government introduced military conscription. Silverman, a pacifist, refused to join the British Army during the First World War. Influenced by the views of Bertrand Russell he registered as a conscientious objector, Silverman served several prison sentences for his beliefs. His son Paul later said: "His idea was that the workers of the world should unite: if the ordinary men on both sides refused to join the armies, the powers-that-be couldn't have had a war. But when war was declared everyone seemed to be infected with war fever and my father found himself very much in a minority."

Another son, Roger Silverman, commented: " Dad was taken to the military barracks but when he got there he wouldn't obey orders and so was arrested and court-martialled. In 1917 he was sentenced to two years of hard labour, and put in prison in Preston." He was later transferred to Wormwood Scrubs. Silverman's experiences in prison made him an advocate of penal reform.

Solicitor

After the war was over Silverman returned to University of Liverpool to complete his studies. In 1921 he successfully applied for a teaching post at the University of Helsinki. Silverman returned to England in 1925 and after further studies he eventually qualified as a solicitor in 1927. Over the next few years he developed a reputation as a solicitor who was willing to defend the interests of the poor in Liverpool. This included workmen's compensation claims and landlord-tenant disputes.

Silverman married Nancy Rubinstein, whose family had fled to Liverpool from the Russian pogroms in the late nineteenth century. Nancy, like her father, was a talented musician. Over the next few years the couple had three sons, Paul, Julian and Roger.

House of Commons

A member of the Labour Party, Silverman was elected as a city councillor in 1932. Soon afterwards he was adopted as the parliamentary candidate for Nelson and Colne and entered the House of Commons following the 1935 General Election. Silverman was one of the leading opponents of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. By 1935 Mosley was expressing strong anti-Semitic views and provocative marches through Jewish districts in London led to riots. Silverman was one of those who supported The passing of the 1936 Public Order Act that made the wearing of political uniforms and private armies illegal, using threatening and abusive words a criminal offence, and gave the Home Secretary the powers to ban marches.

Silverman retained his pacifists views until he discovered what was happening to the Jews in Nazi Germany. He therefore gave his full support to Britain's involvement in the Second World War. However, he was critical of Winston Churchill who promoted the policy of "unconditional surrender", and argued that carefully drafted peace aims would end the war more quickly.

Clement Attlee

When the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election Silverman was expected to be offered a post in the new government. However, Silverman held strong left-wing opinions and Clement Attlee decided against offering him a job. According to the historian, Ben Pimlott, there were other reasons for this decision. Silverman and Ian Mikardo were not given posts because they "belonged to the Chosen People, and he didn't think he wanted any more of them."

Over the next few years Silverman became highly critical of Ernest Bevin and his role as foreign secretary. He was particularly upset by his dealings with the Soviet Union. His biographer, Sarah McCabe, has argued: "Silverman fiercely criticized the foreign secretary's handling of relations with the Soviet Union, for he claimed that Bevin negotiated with Russia as if it were the Communist Party which, in Britain, was both feared and despised; instead he thought that the Soviet Union embodied a great people whose rights and dignity should be respected."

Capital Punishment

Silverman was a strong opponent of capital punishment and in 1948 managed to persuade the House of Commons to agree to a five year suspension of executions. However, this clause in the Criminal Justice Bill was defeated in the House of Lords. As a result Silverman founded the Campaign for the Abolition of the Death Penalty. In 1953 he published his book, Hanged and Innocent?

In November 1954 Silverman, Michael Foot, and three others were expelled from the Labour Party for opposing its nuclear defence policy. Three years later Silverman joined with Kingsley Martin, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Vera Brittain, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Silverman continued to campaign against capital punishment and in 1956 he introduced a private member's Bill for abolition. Once again it was defeated in the House of Lords. Silverman refused to be beaten and as Ian Mikardo has pointed out, Silverman was "incomparably courageous in espousing unpopular causes and facing down a hostile audience." Joseph Mallalieu was less complimentary: "Of all the House of Commons personalities, the most irritating is perhaps Mr Sydney Silverman. He is a cocky man, who throws his shoulders back as if to swell his chest, and thrusts his now bearded chin outward and upward, as if to give him inches. Indeed, he seems over-occupied with his own shortness."

In the 1964 General Election Silverman was returned to the House of Commons with an increased majority despite the fact that one of the candidates, although professedly Labour, made his platform the return of capital punishment for all murder. Harold Wilson, the new prime minister, was also an opponent of the death penalty and his Labour government agreed to introduce legislation to abandon capital punishment for five years. With overwhelming support in the Commons the Lords agreed to pass the measure.

His biographer, Sarah McCabe, has argued: "Silverman had a passion for justice and equality that kept him well to the left of his party, so that he did not commend himself to the establishment. Besides, he was not good at collective action; most of his battles he fought alone, for he enjoyed twisting the tails of his antagonists and might have been denied this enjoyment if he had worked with others." According to his colleague, Richard Crossman: "Silverman was vain, difficult and uncooperative. No one could get him to work in any kind of a group. All his life he remained an individualist back-bencher."

Sydney Silverman died in hospital in Hampstead on 9th February 1968.

Primary Sources

(1) Joseph Mallalieu, The New Stateman (5th May, 1956)

Of all the House of Commons personalities, the most irritating is perhaps Mr Sydney Silverman. He is a cocky man, who throws his shoulders back as if to swell his chest, and thrusts his now bearded chin outward and upward, as if to give him inches. Indeed, he seems over-occupied with his own shortness. As a result even his jokes are often outsize, and he follows them with an extravagant cackle, slapping his knee in an ecstasy of delight. Often the point of these stories is that some body, corporate or otherwise and very likely the National Executive of the party, has been scored off by him.

The irritations which Mr Silverman produces in private are redoubled in public. He will rise from his corner seat below the gangway and, though the House is anxious to pass to other business, argue some technical point. The House sometimes yells in real anger. But he persists. At length the House subsides and waits hopefully for him to be proved wrong. But the most irritating thing about him is that, far more often than not, he is proved right.

This might merely suggest that he is a good lawyer; but there is much more to him than the bare ability to argue technical points. Coming from a large and not particularly well-to-do Liverpool Jewish family, he had to fight for his own legal education through scholarships. When he did begin to practise, he had just sufficient money to open an office and pay a typist one week's wages. But within a short time he was perhaps the most active, and certainly one of the more successful, solicitors in Liverpool. This success was only partly due to his forensic ability in the police courts. Even more, it was due to his passion for what he believes to be right, and to his bias for believing that right is more likely to be on the side of the little man than of the mighty.

This same passion and tenacity has fired his work in the House of Commons. There, too, he has shown a capacity to argue passionately, and be proved right over much more than mere technicalities. In 1945, when Labour had scarcely caught its breath after its sweeping election victory and was preparing to reshape the world, Silverman held up much government business and might even have brought the government down on what seemed a small point - whether old age pensioners should receive their increased pension at once or wait until every new benefit under the projected National Insurance bill could be implemented. The government was for delay, declaring that prior payment to the old was administratively impossible. At first a majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party seemed to be with the government and against Silverman. But he persisted and, in time, a majority began to feel that, after all, the party had committed itself at the election to help the pensioners more explicitly than it had committed to help any other section of the community, and that perhaps what seemed impossible could, with determination, be done without much difficulty. Eventually, the government gave way and the old age pensioners got their increase six months earlier than had been planned.

As with pensioners, so with the unemployed. Silverman protested in 1946 against clauses in the National Insurance bill laying down that a man or a woman should exhaust the right to benefit after a specified period of unemployment. Though he persuaded some 40 other members to follow him into the lobby, the government won easily. Yet, nine years later, official Labour spokesmen began to advocate what he had advocated.

Neither the ability to be right far more often than wrong, nor the ingeniousness and pedantic logic with which he argues his cases, makes friends for Silverman. But his persistence, his courage and sincerity have long ago won him respect. In recent months another quality has begun to produce real affection. That is the quality of being willing and able almost to efface himself, if the issue for which he is fighting demands it.

It is a quality which has been particularly impressive in the debates on hanging which have taken place recently. Silverman had been responsible for introducing the subject to this parliament. When his motion, calling for the suspension of the death penalty, was carried against governmental advice, the government agreed to find time for a private member's bill. By a fluke of the ballot Silverman happened to win the chance to present such a bill himself; and when the day for Second Reading came, some opponents of capital punishment were afraid that its main sponsor might prejudice floating voters against it. Those fears were groundless. Silverman was matter-of-fact, unemotional and unaggressive to the point of dullness. If this was cleverness, it was a cleverness which impressed the House instead of irritating it.

Silverman has spent his lifetime fighting (and in doing so) he has won for himself a special place both in the Labour movement and in the House of Commons. Yet, till now, the acknowledgement he has earned has been touched with mockery and exasperation, as if with all his abilities he were no more than a crank or an ageing bore. But now there are signs that this is changing, perhaps because Silverman himself has been changing.

(2) Sarah McCabe, Dictionary National Biography (1970)

In a powerful address, delivered without notes, Silverman moved the second reading of his new Bill. There was now no doubt about the result in the House of Commons and, in due course, the Bill went to the Lords, which had rejected all previous attempts to abolish capital punishment. But the Campaign for the Abolition of the Death Penalty had done its work well and the Bill went through. This was the climax of Silverman's parliamentary career, for he died before the expiry of the five years' suspension period and did not see the completion of one of his great parliamentary endeavours.

As a final assessment of this astute parliamentarian it can be said that he had a passion for justice and equality that kept him well to the left of his party, so that he did not commend himself to the establishment. Besides, he was not good at collective action; most of his battles he fought alone, for he enjoyed twisting the tails of his antagonists and might have been deprived of this enjoyment if he had worked with others. Nevertheless his contribution to the thinking of his party, to the progress of penal reform, and to the welfare of his fellow Jews remains unquestioned. To his constituents and to his agent he was unfailing in his service. They responded with a warm personal devotion to him.