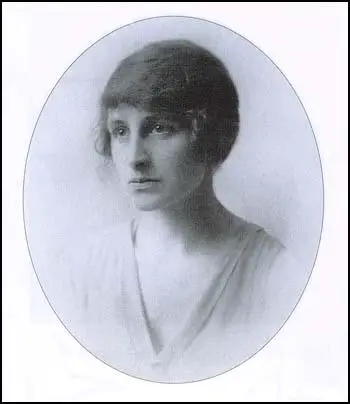

Vera Brittain

Vera Brittain, the only daughter of Thomas Brittain (1864-1935), a wealthy paper manufacturer, and Edith Bervon (1868-1948), was born at Atherstone House, Newcastle-under-Lyme on 29th December 1893. Vera developed a close relationship with her brother, Edward Brittain.

According to her biographer, Alan Bishop: "As they grew up, tended by a governess and servants, in an environment of conservative middle-class values, close supervision, and comparative isolation, brother and sister formed a companionship that was to be a dominant force in Vera's life." She later recalled: "As a child I wrote because it was as natural to me to write as to breathe, and before I could write I invented stories."

Thomas Brittain's two paper mills in Hanley and Cheddleton continued to prosper and in 1905 the family moved to the fashionable spa resort town, Buxton in Derbyshire. The Brittains lived at High Leigh House for two years before moving to an even larger house, Melrose in 1907. Vera was educated at home by a governess and then at a boarding school in Kingswood, where one of the teachers introduced her to the ideas of Dorothea Beale and Emily Davies. "Miss Heath Jones was an ardent though always discreet feminist. She often spoke to me of Dorothea Beale and Emily Davies, lent me books on the woman's movement, and even took me with one or two of the other senior girls in 1911 to what must have been a very mild and constitutional suffrage meeting at Tadworth village." Brittain was also deeply influence by reading Women and Labour by Olive Schreiner.

Oxford University

Vera wanted to go to university but her father believed that the main role of education was to prepare women for marriage. In 1912 she attended a course of Oxford University extension lectures given by the historian John Marriott. Despite the objections of her father, Brittain set about qualifying herself for admission to one of the recently established women's colleges.

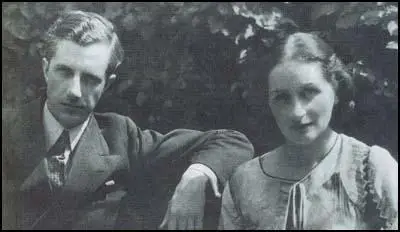

In 1913, her brother, Edward Brittain, introduced Vera to Roland Leighton, one of his friends from Uppingham School. Leighton, who had just won a place Merton College at Oxford University, encouraged her to go to university and in 1914 her father relented and Vera was allowed to go to Somerville College. He gave her a copy of Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm. Roland told her that the main character, Lyndall, reminded him of her. Vera replied in a letter dated 3rd May 1914: "I think I am a little like Lyndall, and would probably be more so in her circumstances, uncovered by the thin veneer of polite social intercourse." Vera wrote in her diary that "he (Roland) seems even in a short acquaintance to share both my faults and my talents and my ideas in a way that I have never found anyone else to yet."

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War Roland and Edward, together with their close friend Victor Richardson, immediately applied for commissions in the British Army. Vera wrote to Roland about his decision to take part in the war: "I don't know whether your feelings about war are those of a militarist or not; I always call myself a non-militarist, yet the raging of these elemental forces fascinates me, horribly but powerfully, as it does you. You find beauty in it too; certainly war seems to bring out all that is noble in human nature, but against that you can say it brings out all the barbarous too. But whether it is noble or barbarous I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration."

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Edward Brittain introduced Vera to his friend, Geoffrey Thurlow. He was suffering from shellshock after experiencing heavy bombardment at Ypres in February 1915. He was sent back to England and was at hospital at Fishmongers' Hall when he was visited by Vera. She wrote to Roland Leighton on 11th October 1915: "I liked Thurlow so much. Whatever Edward's failings, I must say he has an admirable faculty for choosing his friends well... But seeing Thurlow for a short time made me feel rather sad, for the nicer such people as he are, the more they serve to emphasize in some indirect way, the fact of your immense superiority over the very best of them!"

By the end of her first year at Somerville College she decided it was her duty to abandon her academic career to serve her country. During the summer of 1915 she worked at the Devonshire Hospital in Buxton, as a nursing assistant, tending wounded soldiers. On 28th June 1915 she wrote to Roland pointing out: "I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either... The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless."

VAD Nurse

Vera applied to join the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) as a nurse and in November 1915 was posted to the First London General Hospital at Camberwell. Vera found this a traumatic experience. On 7th November 1915 she wrote to Roland Leighton: "I have only one wish in life now and that is for the ending of the war. I wonder how much really all you have seen and done has changed you. Personally, after seeing some of the dreadful things I have to see here, I feel I shall never be the same person again, and wonder if, when the war does end, I shall have forgotten how to laugh... One day last week I came away from a really terrible amputation dressing I had been assisting at - it was the first after the operation - with my hands covered with blood and my mind full of a passionate fury at the wickedness of war, and I wished I had never been born."

She found dealing with the parents of wounded soldiers particularly difficult: "Today is visiting day, and the parents of a boy of 20 who looks and behaves like 16 are coming all the way from South Wales to see him. He has lost one eye, had his head trepanned and has fourteen other wounds, and they haven't seen him since he went to the front. He is the most battered little object you ever saw. I dread watching them see him for the first time."

Vera Brittain wrote in her diary: "Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line. We have heaps of gassed cases at present: there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes - sometimes temporally, some times permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke."

Death of Roland Leighton

Vera became engaged to Roland Leighton, while he was on leave in August 1915. On his return to France he was stationed in trenches near Hebuterne, north of Albert. On the 26th November 1915 he wrote a letter to Vera that highlighted his disillusionment with the war. "It all seems such a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty. And if one does not even get a letter occasionally from someone who despite his shortcomings perhaps understands and sympathises it must make it all the worse... until one may possibly wonder whether it would not have been better to have met him at all or at any rate until afterwards. I sometimes wish for your sake that it had happened that way."

On the night of 22nd December 1915 he was ordered to repair the barbed wire in front of his trenches. It was a moonlit night with the Germans only a hundred yards away and Roland Leighton was shot by a sniper. His last words were: "They got me in the stomach, and it's bad." He died of his wounds at the military hospital at Louvencourt on 23rd December 1915. He is buried in the military cemetery near Doullens.

In her autobiography Vera recalled visiting Roland's family home in Hassocks. "I arrived at the cottage that morning to find his mother and sister standing in helpless distress in the midst of his returned kit, which was lying, just opened, all over the floor. The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and I wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics - the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rages made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant."

On 3rd January 1916, Vera returned to First London General Hospital at Camberwell. In his book, Letters From a Lost Generation (1998), Alan Bishop argued that "nursing proved an intolerable strain while her grief for Roland was still so raw on the support" of Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were both recovering in military hospitals.

Edward Brittain

Edward Brittain arrived on the Western Front at the beginning of 1916. On 27th February he wrote to his sister, Vera Brittain. "Ordinary risks of stray shots or ricochets off a sandbag or the chance of getting hit when you look over the parapet in the night time - you hardly ever do in the day time but use periscopes - are daily to be encountered. But far the most dangerous thing is going out on patrol in No Man's Land. You take bombs in case you should meet a hostile patrol, but you might be surrounded, you might be seen especially if you go very close to their line and anyhow. Very lights are always being sent up and they make night into day so you have to keep down and quite still, and you might get almost on top of their listening post if you are not sure where it is."

On 8th January 1916 Victor Richardson suggested a meeting with Vera. "May I come and see you on Wednesday afternoon? I suggest this next Wednesday, because I am on guard at one of the Arsenal entrances during the week, and as it is not an important position I could leave my coadjutor in charge for the afternoon, and disappear - without leave..... Of course if you do not feel inclined to see people I shall quite understand. If I do not hear from you I shall assume this to be the case." Vera agreed to the meeting, as she told her brother, Edward Brittain: "I had tea with Victor on Wednesday. Of course we talked of Roland the whole time."

Vera wrote to her brother on 23rd February about her new friend, Geoffrey Thurlow: "I saw that Thurlow had been wounded - I suppose in the recent fighting at Ypres. I have almost loved him since his little letter to me after Roland died, and I can't tell you how anxiously I hope that he is not badly hurt." Vera went to visit Geoffrey on 27th February. Later that day she wrote to her brother about his condition: "I have just been to see Thurlow at Fishmongers' Hall Hospital, London Bridge. He is only very slightly wounded on the left side of his face; fortunately his eyes, nose and mouth are quite untouched. In fact he says he won't even have a scar left, and the wound is healing with a depressing rapidity.... He was apparently wounded in the bombardment, before all the trench fighting began. He thinks hardly any of his battalion are left now."

Vera told Edward Brittain that Thurlow was suffering from the consequences of serving on the front-line: "Thurlow was... sitting before a gas stove, with a green dressing gown on and a brown blanket over his knees. He seems to feel the cold a great deal, which must be owing to the shock, and also for the same reason his nerves are very bad, so he has been given two months sick leave."

Thurlow told Vera that he was keen to return to France. "Of course he doesn't want to go back a bit, but since he has to go, he's got the same feeling as he had before, that he wants to go out quickly and get it over. He says he finds the anticipation so much worse than the things themselves, whatever they are. He says he is not a bit of a success out there because he is so afraid of being afraid, and he hates the way all his men's eyes are fixed on him when anything big is on, partly to see how he will take it, partly because they are afraid of anything happening to him. He says he objects to war on principle, and is a non-militarist very strongly at heart. I think it was very brave of him to join almost at once as he did... It is easy to see he is suffering from shock; he looks rather a ghost now he is sitting up, talks even more jerkily than before, and works his fingers about nervously while he is talking."

Vera found nursing badly wounded men very difficult: "He (Victor Richardson) has been near death, I know, but he hasn't seen men with mutilations such as I have, though he may have heard a lot about them; I must admit that when, as I am doing at present, I have to deal with men who have only half a face left and the other side bashed in out of recognition, or part of their skull torn away, or both feet off, or an arm blown off at the shoulder."

Edward took part in the Battle of the Somme on 1st July 1916. The author of Letters From a Lost Generation (1998) has pointed out: "While his company was waiting to go over, the wounded from an earlier part of the attack began to crowd into the trenches. Then part of the regiment in front began to retreat, throwing Edward's men into a panic. He had to return to the trenches twice to exhort them to follow him over the parapet. About ninety yards along No-Man's-Land, Edward was hit by a bullet through his thigh. He fell down and crawled into a shell hole. Soon afterwards a shell burst close to him and a splinter from it went through his left arm. The pain was so great that for the first time he lost his nerve and cried out. After about an hour and a half, he noticed that the machine-gun fire was slackening, and started a horrifying crawl back through the dead and wounded to the safety of the British trenches."

Edward Brittain was sent to First London General Hospital at Camberwell where his sister was working as a nurse. According to Alan Bishop: "After receiving permission from his Matron to visit him, Vera hurried to Edward's bedside. He was struggling to eat breakfast with only one hand, his left arm was stiff and bandaged, but he appeared happy and relieved. Edward would remain in the hospital for three weeks before beginning a prolonged period of convalescent leave." On 24th August it was announced that Brittain had been awarded the Military Cross.

On 24th September, 1916, Vera received news that she was being posted to Malta. Her brother, Edward Brittain wrote on the 5th October: "The night of the day you left London the Zeppelins dropped 4 bombs at Purley somewhere up that hill where we walked one afternoon when I was still bad only about 600yds from the house but it did no damage. A foolish woman came out into the road and therefore received some shrapnel in one eye from one of our own guns but otherwise there was no damage except windows and a pillar box."

Vera continued to communicate with Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow. Richardson, who was a member of the 9th King's Royal Rifles was stationed on a quiet sector of the Western Front: "I have so far come across nothing more gruesome than a few very dead Frenchman in No Man's Land, so cannot give you very thrilling descriptions. The thing one appreciates in the life here more than anything else is the truly charming spirit of good fellowship and freedom from pettiness that prevails everywhere." Thurlow wrote on 18th November 1916: "Since my last letter much has happened - we have been to the war again and the weather treated us abominably: however our battalion did well taking an important Hun trench - we didn't go over the top but had to clean up and hang on to the trench. Luckily we had no officer casualties though there were many among the men. But as our number of officers is at present the irreducible minimum perhaps this accounts for it."

Edward Brittain received his Military Cross from George V on 16th December 1916. In a letter to Vera he wrote: "We were instructed what to do by a Colonel who I believe is the King's special private secretary and then the show started. One by one we walked into an adjoining room about 6 paces - halt - left turn - bow - 2 paces forward - King pins on cross - shake hands - pace back - bow - right turn and slope off by another door... The King spoke to a few of us including me; he said "I hope you have quite recovered from your wound", to which I replied "Very nearly thank you, Sir", and then went out with the cross in my pocket in a case. I met Mother just outside and we went off towards Victoria thinking we had quite escaped all the photographers, but unfortunately one beast from the Daily Mirror saw us and took us, but luckily it does not seem to have come out well as it is rather bad form to have your photo in a cheap rag if avoidable."

On 20th February 1917, Vera wrote a very personal letter to Edward: "But where you and I are concerned, sex by itself doesn't interest us unless it is united with brains and personality; in fact we rather think of the latter first, and the person's sex afterwards... I think very probably that older women will appeal to you much more than younger ones, as they do me. This means that you will probably have to wait a good many years before you find anyone you could wish to marry, but I don't think this need worry you, for there is plenty of time, and very often people who wait get something well worth waiting for."

In a letter to Edward Brittain on 2nd April 1917, Vera reported that some of the staff had been posted to Salonika. "I wish they would send some of us.... I would volunteer like a shot. Not because the city of malaria and mosquitoes and air-raids and odours suggests many attractions, but because this wandering, unsettled, indefinite sort of life makes one yearn to taste as much as one can of what the war has placed within human experience."

Victor Richardson & Geoffrey Thurlow

Victor Richardson was badly wounded during an attack at Arras on 9th April 1917. Vera wrote to her mother, Edith Brittain: "There really does not seem much point in writing anything until I hear further news of Victor, for I cannot think of anything else... I knew he was destined for some great action, even as I knew beforehand about Edward, for only about a week ago I had a most pathetic letter from him - a virtual farewell. It is dreadful to be so far away and all among strangers.... Poor Edward! What a bad time the Three Musketeers have had!"

Richardson was sent back to London where he received specialist treatment at a hospital in Chelsea. Edward Brittain, visited him in hospital, and then wrote to Vera, about his condition: "It is not known yet whether Victor will die or not, but his left eye was removed in France and the specialist who saw him thinks it is almost certain that the sight of the right eye has gone too... The bullet - probably from a machine-gun - went in just behind the left eye and went very slightly upwards but not I'm afraid enough to clear the right eye; the bullet is not yet out though very close to the right edge of the temple; it is expected that it will work through of its own accord... We are told that he may remain in his present condition for a week. I don't think he will die suddenly but of course the brain must be injured and it depends upon how bad the injury is. I am inclined to think it would be better that he should die; I would far rather die myself than lose all that we have most dearly loved, but I think we hardly bargained for this. Sight is really a more precious gift than life."

Geoffrey Thurlow was killed in action at Monchy-le-Preux on 23rd April 1917. Three days later, Captain J. W. Daniel, wrote to Edward Brittain, about Thurlow's death: "The hun had got us held up and the leading battalions of the Brigade had failed to get their objective. The battalion came up in close support through a very heavy barrage, but managed to get into the trench - of which the Boshe still held a part... I sent a message to Geoffrey to push along the trench and find out if possible what was happening on the right. the trench was in a bad condition and rather congested, so he got out on the top. Unfortunately the Boche snipers were very active and he was soon hit through the lungs. Everything was done to make him as comfortable as possible, but he died lying on a stretcher about fifteen minutes later."

Edward wrote to Vera about Thurlow: "Always a splendid friend with a splendid heart and a man who won't be forgotten by you or me however long or short a time we may live. Dear child, there is no more to say; we have lost almost all there was to lose and what have we gained? Truly as you say has patriotism worn very very threadbare."

Vera replied: "I can't tell you how I shall miss Geoffrey - I think he meant more to me that anyone after Roland and you. as for you I dare not think how lonely you must feel with him dead and Victor perhaps worse, for it makes me too impatient of the time that must elapse before I can see you - I may not even be able to start for two or three weeks. Geoffrey and I had become very friendly indeed in letters of late, and used to write at least once a week... After Roland he was the straightest, soundest, most upright and idealistic person I have ever known."

Vera decided to return home after the death of Geoffrey Thurlow and the serious injuries suffered by Victor Richardson. She told her brother: "As soon as the cable came saying that Geoffrey was killed, only a few hours after the one saying that Victor was hopelessly blind, I knew I must come home. It will be easier to explain when I see you, also - perhaps - to consult you about something I can't possibly discuss in a letter. Anyone could take my place here, but I know that nobody else could take the place that I could fill just now at home."

Edward Brittain went to visit Victor and on 7th May he told his sister: "He was told last Wednesday that he will probably never see again, but he is marvellously cheerful.... He is perfectly sensible in every way and I don't think there is the very least doubt that he will live. He said that the last few days had been rather bitter. He hasn't given up hope himself about his sight."

Vera arrived in London on 28th May 1917. The next ten days she spent at Victor's bedside. As Alan Bishop points out: "His mental faculties appeared to be in no way impaired. On 8 June, however, there was a sudden change in his condition. In the middle of the night he experienced a miniature explosion in the head, and subsequently became very distressed and disoriented. By the time his family reached the hospital Victor had become delirious." Victor Richardson died of a cerebral abscess on 9th June, 1917 and is buried in Hove. He was awarded the Military Cross posthumously.

Edward returned to the Western Front in June 1917. Vera decided she wanted to be as close to her brother as possible and in July she returned to duty with the Voluntary Aid Detachment and requested a posting to France. On 30th June 1917 Edward wrote to Vera: "The unexpected has happened again and I am in for another July 1st (Battle of the Somme)... You know that, as I promised, I will try to come back if I am killed. It is all very sudden and it is bad luck that I am here in time, but still it must be. All the love there is in life or death."

On 3th August 1917, Vera joined a small draft of nurses who were being sent out to the 24th General Hospital at Étaples. She wrote to her mother on 5th August: "I arrived here yesterday afternoon; the hospital is about a mile out of the town, on the side of the hill, in a large clearing surrounded on three sides by woods... The hospital is frantically busy and we were very much welcomed.... You will be surprised to hear that at present I am nursing German prisoners. My ward is entirely reserved for the most acute German surgical cases... The majority are more or less dying; never, even at the 1st London during the Somme push, have I seen such dreadful wounds. Consequently they are all too ill to be aggressive, and one forgets that they are the enemy and can only remember that they are suffering human beings."

Vera had to deal with men suffering from mustard gas attacks. She wrote to her mother on 5th December 1917: "We have heaps of gassed cases at present who came in a day or two ago; there are ten in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of ten cases - of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things burnt and blistered all over with great mustard coloured suppurating blisters, with blinded eyes - sometimes temporally, sometimes permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke. The only thing one can say it that such severe cases don't last long; either they die soon or else improve - usually the former; they certainly don't reach England in the state we have them here, and yet people persist in saying that God made War, when there are such inventions of the Devil about."

In her autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933), Vera recorded: "Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line.... The strain is very, very great. The enemy is within shelling distance - refugee sisters crowding in with nerves all awry - bright moonlight, and aeroplanes carrying machine guns - ambulance trains jolting into the siding, all day, all night - gassed men on stretchers clawing the air - dying men reeking with mud and foul green stained bandages, shrieking and writhing in a grotesque travesty of manhood - dead men with fixed empty eyes and shiny yellow faces."

Death of Edward Brittain

In September 1917 Edward Brittain took part in a major offensive. He wrote to Vera on the 23rd: "We came out (of the front-line) last night... had about 50 casualties including one officer in the company - the best officer of course. I ought to have been slain myself heaps of times but I seem to be here still. Harrison has arrived back and it is quite a relief to hand the company over for a bit."

The following month Edward was sent to Ypres for the offensive at Passchendaele. He wrote to Vera on 7th October 1917: "My leave seems to have been stopped for the present for some reason or other and also we are probably going up to Ypres again tonight to provide working-parties etc. which is as unexpected as it is objectionable; it is filthy weather, cold and pouring with rain and I have just caught a bad cold and so am not particularly pleased with life."

In November 1917 Edward Brittain and the 11th Sherwood Foresters were posted to the Italian Front in the Alps above Vicenza, following the humiliating rout of the Italian Army at Caporetto. On 15th November 1917, he wrote to Vera: "We marched through the city yesterday - it is old, picturesque and rather sleepy with narrow streets and pungent smells; we have been accorded a most hearty reception all the way and have been presented with anything from bottles of so-called phiz, to manifestos issued by mayors of towns; flowers and postcards were the most frequent tributes."

While she was in Étaples Vera received a letter from her father informing her that her mother had suffered a complete breakdown and entered a nursing home in Mayfair, and that it was her duty to leave France immediately and return home to Kensington. Vera arrived back in England in April 1918 and arranged for her mother to return home. According to the author of Letters From a Lost Generation (1998): "Vera... took charge of the household. But it was with a strong air of resentment that she tried to reaccustom herself to the dull monotony of civilian life."

On 15th June, 1918, the Austrian Army launched a surprise attack with a heavy bombardment of the British front-line along the bottom of the San Sisto Ridge. Edward Brittain led his men in a counter-offensive and had regained the lost positions, but soon afterwards, he was shot through the head by a sniper and had died instantaneously. He was buried with four other officers in the small cemetery at Granezza.

Alan Bishop points out that his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hudson, had ordered an investigation into Brittain's homosexuality: "Shortly before the action in which he was killed, Edward had been faced with an enquiry and, in all probability, a court martial when his battalion came out of the line, because of his involvement with men in his company. It remains a possibility that, faced with the disgrace of a court martial, Edward went into battle deliberately seeking to be killed."

Somerville College

After the Armistice Vera returned to Somerville College. She later recalled: "At Somerville the news of my intention to change my School was received without enthusiasm; in English I had been regarded as a probable First, but in the field of History I had forgotten even such information as I had once derived from Miss Heath Jones's political and religious teaching... I never regretted the decision, for in studying international relations, and the great diplomatic agreements of the nineteenth century, I discovered that human nature does change, does learn to hate oppression, to deprecate the spirit of revenge, to be revolted by acts of cruelty, and at last to embody these changes of heart." She added that she hoped that studing history would help her "understand how the whole calamity (of the war) had happened, to know why it had been possible for me and my contemporaries, through our own ignorance and others' ingenuity, to be used, hypnotised and slaughtered".

At Oxford University Vera met Winifred Holtby. She explained in her autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933): "I was staring gloomily at the Oxford engravings and photographs graphs of the Dolomites which clustered together so companionably upon the Dean's study wall, when Winifred Holtby burst suddenly in upon this morose atmosphere of ruminant lethargy. Superbly tall, and vigorous as the young Diana with her long straight limbs and her golden hair, her vitality smote with the effect of a blow upon my jaded nerves. Only too well aware that I had lost that youth and energy for ever, I found myself furiously resenting its possessor. Obstinately disregarding the strong-featured, sensitive face and the eager, shining blue eyes, I felt quite triumphant because - having returned from France less than a month before - she didn't appear to have read any of the books which the Dean had suggested as indispensable introductions to our Period."

Vera and Winifred graduated together in 1921 and they moved to London where they hoped to establish themselves as writers. Vera's first two novels, The Dark Tide (1923) and Not Without Honour (1925) sold badly and were ignored by the critics. However, Winifred had more success with Anderby Wold (1923) and The Crowded Street (1924). Vera had more success with her journalism and in 1920s wrote for the feminist journal, Time and Tide. Vera also published two books on the role of women, Women's Work in Modern Britain (1928) and Halcyon or the Future of Monogamy (1929).

Marriage to George Catlin

In June 1925 Vera married the academic, George Edward Catlin. As Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "When Brittain and Catlin set up home in London after their marriage, Holtby joined them as the third member of the household. Catlin never overcame his resentment at his wife's friendship with the woman Vera described as her second self. He knew, in spite of all the gossip to the contrary, that the Brittain-Holtby relationship had never been a lesbian one, but its closeness still rankled."

Vera and her husband moved to the United States when her husband became a a professor at Cornell University. Vera found it difficult to settle in America and after the birth of her two children, John (1927) and Shirley (1930) she moved back to England where she lived with Winifred Holtby. Vera's daughter, Shirley Williams, later wrote: "Some critics and commentators have suggested that their relationship must have been a lesbian one. My mother deeply resented this. She felt that it was inspired by a subtle anti-feminism to the effect that women could never be real friends unless there was a sexual motivation, while the friendships of men had been celebrated in literature from classical times. My mother was instinctively heterosexual. But as a famous woman author holding progressive opinions, she became an icon to feminists and in particular to lesbian feminists." However, Vera's husband, George Edward Catlin, did not approve of the relationship. He wrote later: "You preferred her to me. It humiliated me and ate me up.

In her first volume of autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933) Brittain wrote about her struggle for education and her experiences as a nurse during the First World War. It also told of her relationship with her brother, Edward Brittain, and her love of Roland Leighton, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow. The novelist, Margaret Storm Jameson, reviewed the book in the Sunday Times and said that as a representation of war from a woman's perspective "makes it unforgettable". It was an immediate bestseller in Britain and the United States.

Vera Brittain became a full-time writer. In her autobiography, Shirley Williams wrote: "Determinedly professional, my mother was at work in her study by 10am, after reading the newspapers and the morning's letters, sorting out the shopping lists and paying the bills. Her study was a sacred place, of blotters and pens in black-and-gold stands, of carefully ranged notepaper and envelopes, and of manuscripts composed in her neat, rounded script. Only death, war or a serious accident would justify interrupting her there."

On 7th July, 1934, the British Union of Fascists held a large rally at Olympia. About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Margaret Storm Jameson, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Jameson argued in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality? There was a public outcry about this violence and Lord Rothermere and his Daily Mail withdrew its support of the BUF. Over the next few months membership went into decline.

Death of Winifred Holtby

In the early 1930s Winifred Holtby began to suffer with high-blood-pressure, recurrent headaches and bouts of lassitude. Eventually she was diagnosed as suffering from Bright's Disease. Her doctor told her that she probably only had two years to live. Aware she was dying, Winifred put all her remaining energy into what became her most important book, South Riding.

Vera Brittain later recalled that she asked Harry Pearson to tell "Winifred he loved her and always had; that he'd like to marry her when she was better". She added that on 28th September, 1935: "At about three o'clock Hilda Reid rang up to say that Dr. Obermer had been round to the home and had already put Winifred under morphia; she was now unconscious and would never be permitted to come back to consciousness again. Later I learnt that Dr. Obermer did this because after Harry had been with Winifred she was so happy and excited that he feared a violent convulsion for her, with physical pain and mental anguish; and that he thought it best to let her go out on that moment of happiness, with the cruel realization that what she was hoping could never be fulfilled."

The following day Vera went to visit Winifred at the nursing home at 23 Devonshire Street in Marylebone: "Shortly after six o'clock I realised that she was breathing more shallowly, while her pulse was slower and weaker. After almost a quarter of an hour her pulse, which I was holding, had almost stopped, and her breathing seemed to come from her throat only... It was strange, incredible, after all the years of our friendship and all that we had shared together, to feel her life flickering out under my hand. Suddenly her pulse stopped; she had given two or three deeper breaths and then these ceased and I thought she had stopped breathing too; but after a moment came one final, lingering sigh, and then everything was at an end."

Winifred Holtby died on 29th September, 1935. Vera Brittain was Winifred's literary executor, and was determined to make sure South Riding was published. However, as Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "The major obstacle she faced was the indomitable figure of Holtby's mother, Alice, the first woman alderman of the East Riding. She feared that her daughter's depiction of local government, allied to the vein of satire and puckish mischief familiar from her earlier books, might expose her own job to criticism and ridicule... Alice Holtby remained obdurate in her opposition to the book's publication, forcing Brittain to adopt a strategy of mild subterfuge, negotiating the uncorrected typescript through probate in order to have the novel ready for publication by Collins in the spring of 1936."

In 1935 Vera's father committed suicide. Grief-stricken by the deaths of Winifred and her father, Vera struggled to complete her own finest novel, Honourable Estate: a Novel of Transition (1936). According to her biographer, Alan Bishop, it was a "long, ambitious, feminist, pacifist, a family saga based on the recent history of the Brittain and Catlin families. It greatly disturbed George Catlin for it drew particularly on the diary of his mother, who had abandoned son and husband."

Peace Pledge Union

Brittain also became friendly with Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral. He had been an army chaplain during the First World War. A committed pacifist, he was concerned by the failure of the major nations to agree to international disarmament and on 16th October 1934, he had a letter published in the Manchester Guardian inviting men to send him a postcard giving their undertaking to "renounce war and never again to support another." Within two days 2,500 men responded and over the next few weeks around 30,000 pledged their support for Sheppard's campaign.

In July 1935 Sheppard chaired a meeting of 7,000 members of his new organization at the Albert Hall in London. Eventually named the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), it achieved 100,000 members over the next few months. The organization now included other prominent religious, political and literary figures including Brittain, Arthur Ponsonby, George Lansbury, Margaret Storm Jameson, Wilfred Wellock, Max Plowman, Maude Royden, Frank P. Crozier, Alfred Salter, Ada Salter, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell.

In the 1930s Brittain became a pacifist and in 1934 supported Richard Sheppard and his Peace Pledge Union and was one of its leaders during the Second World War. From September 1939 she began publishing Letters to Peace Lovers, a small journal that expressed her views on the war. This made her extremely unpopular as the journal criticised the government for bombing urban areas in Nazi Germany.

Vera wrote about her relationship with Winifred Holtby in her book Testament of Friendship (1940). In her books, England's Hour: an Autobiography (1941) and Humiliation with Honour (1943), Brittain attempted to explain her pacifism in her book Humiliation with Honour. This was followed by Seeds of Chaos, an attack on the government's policy of area bombing.

Novelist

Her final two novels, Account Rendered (1945) and Born 1925: a Novel of Youth (1948), both sold badly and as a result she turned away from fiction. Other books by Brittain included a history of the women's movement, Lady into Women (1953), a second volume of autobiography, Testament of Experience (1957), Women at Oxford (1960), Pethick-Lawrence: a Portrait (1963), a biography of peace-campaigner, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, The Rebel Passion: a Short History of some Pioneer Peacemakers (1964) and Radclyffe Hall: a Case of Obscenity? (1968), an account of the lesbian novelist, Radclyffe Hall.

A strong opponent of nuclear weapons, in 1957 Brittain joined with Kingsley Martin, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Victor Gollancz, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Vera Brittain remained active in the peace movement until her death on 29th March 1970 in a nursing home in Wimbledon. In accordance with her last wishes, Vera's ashes were scattered over Edward's grave at the cemetery of Granezza, in September 1970.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1906 Vera Brittain was sent to Kingswood School.

At the age of thirteen I was sent away to school at the recently founded St Monica's at Kingswood in Surrey. Miss Heath Jones was an ardent though always discreet feminist. She often spoke to me of Dorothea Beale and Emily Davies, lent me books on the woman's movement, and even took me with one or two of the other senior girls in 1911 to what must have been a very mild and constitutional suffrage meeting at Tadworth village.

Her encouragement even prevailed upon us to read the newspaper, which were then quite unusual adjuncts to teaching in girls' private schools. We were never, of course, allowed to have the papers themselves - our innocent eyes might have strayed from foreign affairs to the evidence being taken by the Royal Commission on Marriage and Divorce or the Report of the International Paris Conference for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic.

(2) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (1st October, 1914)

I don't know whether your feelings about war are those of a militarist or not; I always call myself a non-militarist, yet the raging of these elemental forces fascinates me, horribly but powerfully, as it does you. You find beauty in it too; certainly war seems to bring out all that is noble in human nature, but against that you can say it brings out all the barbarous too. But whether it is noble or barbarous I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration.

(3) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (13th May, 1915)

I have just had a letter from one of my great friends at school, whose brother, who is in the Buffs, was wounded near St Julien on the 3rd and is now in hospital in London. There are only 3 officers including him, left of his battalion and only 159 men out of 5000. North of Ypres must indeed have been hell. This man hadn't slept or had his clothes off for 24 days before being wounded. They had to hold their trenches while under shell fire without a single gun to help them, and watched the Germans forming to attack them without being able to do anything. Their trenches were taken and as he was lying wounded he saw the Germans bayoneting his men and and several of his friends who were wounded.

(4) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (30th May, 1915)

A more than usually heated conflict is going on in the papers about the war in general and conscription in particular. Lord Northcliffe's papers seem to be attacking anyone in authority, especially Lord Kitchener, and the rest of the press is attacking Lord Northcliffe. If the subjects of their controversy were not so immense and terrible it would be quite amusing, but as it is it seems a dreadful state of affairs that the authorities are quarrelling among themselves at home while men who are in their hands are dying for them abroad... What do you think about conscription yourself? I think men at the front must surely know more about it than the squabblers in the Cabinet. Edward is very much against it; he says it would to a great extent destroy the morale of our army, which is the chief factor in rendering it superior to other armies in general.

(5) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (30th May, 1915)

There was a Zeppelin raid on London at last, in the early hours of yesterday morning... There were 5 deaths and a good many serious injuries and several fires. People have tried to telephone through to their relations and were not allowed; owing to the secrecy preserved several wild rumours got about, one actually to the effect that Liverpool St. Station was burnt down!

(6) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton from Buxton (28th June, 1915)

I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either...

The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless...

I have various things to do, all of which belong to the kind of work which is called probationers' work. Another nurse & I have three wards to look after between us. Generally I do two & she does one, as she has other work like massage to do which does not come within my sphere. I have to take the men their breakfasts (they are nearly all in bed for breakfast), prepare the tables for the doctor, with hot water etc, tidy up & dust the wards & make the beds. These latter are not made in the ordinary way but in a particular method you have to learn how to do, & are called medical beds. Not every sick person has a medical bed, but cases of rheumatism always do.

(7) Alan Bishop, Letters From a Lost Generation (1998)

Roland's leave lasted for just under a week, during which he and Vera agreed to become officially engaged "for three years or the duration of the War". After spending the first night at Buxton, they travelled down to Lowestoft to be with his family. In some ways it was an unsatisfactory time for both of them, getting used to each other again after so many months of separation. They enjoyed only one true moment of intimacy as they sat alone on a cliff path, the afternoon before their departure. Silently drawing Vera closer to him, Roland rested his head on her shoulder for a while, and then kissed her. As Vera had to report for duty, back at the Devonshire, on 24 August and Roland was not returning to France until the end of the week, they had agreed that he should see her off at St Pancras. At the station, on 23 August, he kissed her goodbye and then, almost furtively, wiped his eyes with his handkerchief: "I hadn't realized until then that this quiet and self-contained person was suffering so much," Vera wrote in her diary. As the train began to move she had time to kiss him and murmur "Goodbye". She stood by the door and watched him walk back through the crowd. "He never turned again. What I could see of his face was set and pale."

(8) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (7th November, 1915)

I have only one wish in life now and that is for the ending of the war. I wonder how much really all you have seen and done has changed you. Personally, after seeing some of the dreadful things I have to see here, I feel I shall never be the same person again, and wonder if, when the war does end, I shall have forgotten how to laugh... One day last week I came away from a really terrible amputation dressing I had been assisting at - it was the first after the operation - with my hands covered with blood and my mind full of a passionate fury at the wickedness of war, and I wished I had never been born...

I am just going back to duty. Today is visiting day, and the parents of a boy of 20 who looks and behaves like 16 are coming all the way from South Wales to see him. He has lost one eye, had his head trepanned and has fourteen other wounds, and they haven't seen him since he went to the front. He is the most battered little object you ever saw. I dread watching them see him for the first time.

(9) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (10th September, 1915)

What do you think of this for an "agony" in The Times? "Lady, fiancé killed, will gladly marry officer totally blinded or otherwise incapacitated by the War."

At first sight it is a little startling. Afterwards the tragedy of it dawns on you. The lady (probably more than a girl or she would have called herself "young lady"; they always do) doubtless has no particular gift or qualification, and does not want to face the dreariness of an unoccupied and unattached old mainenhood. But the only person she loved is dead; all men are alike to her and it is a matter of indifference whom she marries, so she thinks she may as well marry someone who really needs her. The man, she thinks, being blind or maimed for life will not have much opportunity of falling in love with anyone and even if he does will not be able to say so. But he will need a perpetual nurse, and she if married to him can do more for him than an ordinary nurse and will perhaps find some relief for her sorrow in devoting her life to him.... It is purely a business arrangement, with an element of self-sacrifice which redeems it from utter sordidness. Quite an idea, isn't it!

(10) Roland Leighton, letter to Vera Brittain (26th November, 1915)

Just a short letter before I go to bed. The Battalion is back in the trenches now and I am writing in the dugout that I share with the doctor. It is very comfortable (possessing among other things an easy chair, stove, an oil lamp, a table complete with tablecloth) and I am feeling pleasantly tired but not actually sleepy. Through the door I can see little mounds of snow that are the parapets of trenches, a short stretch of railway line, and a very brilliant full moon. I wonder what you are doing. Asleep I hope - or sitting in front of a fire in blue and white striped pyjamas? I should so like to see you in blue and white pyjamas You are always very correctly dressed when I find you; and usually somewhere near a railway station. I once saw you in a dressing gown with your hair down your back playing an accompaniment for Edward in the Buxton drawing room....

It all seems such a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty. And if one does not even get a letter occasionally from someone who despite his shortcomings perhaps understands and sympathises it must make it all the worse... until one may possibly wonder whether it would not have been better to have met him at all or at any rate until afterwards. I sometimes wish for your sake that it had happened that way.

(11) Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton (15th December, 1915)

I have just had my December night-off, and have had a most delightful time. I went down to the Grand Hotel at Brighton, which I had never seen before. Fortunately lack of sleep does not make me sleepy, and I thoroughly enjoyed yesterday, which was made still better by most glorious weather. The war of course is much in evidence down there, but not so much in its sadder aspects, such as I see here. At Brighton there is more of the social side of the war, if one can so express it. The Grand Hotel possessed an abundance of honeymoon couples and slightly wounded officers, and officers belonging to the various battalions stationed down there. It was delightful to take off my uniform and get into some decent clothes, and wrap myself up in my beloved fur coat and feel really warm for the first time for weeks.

(12) Letter from Roland Leighton to Vera Brittain (August, 1915)

Among this chaos of twisted iron and splintered timber and shapeless earth are the fleshless, blackened bones of simple men who poured out their red, sweet wine of youth unknowing, for nothing more tangible than Honour or their Country's Glory or another's Lust of Power. Let him who thinks that war is a glorious golden thing, who loves to roll forth stirring words of exhortation, invoking Honour and Praise and Valour and Love of Country. Let him look at a little pile of sodden grey rags that cover half a skull and a shine bone and what might have been its ribs, or at this skeleton lying on its side, resting half-crouching as it fell, supported on one arm, perfect but that it is headless, and with the tattered clothing still draped around it; and let him realise how grand and glorious a thing it is to have distilled all Youth and Joy and Life into a foetid heap of hideous putrescence.

(13) Vera Brittain's boyfriend Roland Leighton, was killed on 23rd December 1916. Soon afterwards she visited his family home in Hassocks in Sussex.

I arrived at the cottage that morning to find his mother and sister standing in helpless distress in the midst of his returned kit, which was lying, just opened, all over the floor. The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and I wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics - the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rages made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant. Eighteen months afterwards the smell of Etaples village, though fainter and more diffused, brought back to me the memory of those poor remnants of patriotism.

(14) Vera Brittain letter to Edward Brittain (31st May, 1916)

He (Victor Richardson) has been near death, I know, but he hasn't seen men with mutilations such as I have, though he may have heard a lot about them; I must admit that when, as I am doing at present, I have to deal with men who have only half a face left and the other side bashed in out of recognition, or part of their skull torn away, or both feet off, or an arm blown off at the shoulder.

(15) Vera Brittain letter to Edward Brittain (20th February, 1917)

You and I are not only aesthetic but ascetic - at any rate in regard to sex. Or perhaps, since "ascetic" implies rather a lack of emotion, it would be more correct to say exclusive - Geoffrey is very much this, and Victor, and Roland was. What I mean by this is, that so many people are attracted by the opposite sex simply because it is the opposite sex - the average officer and the average "nice girl" demand, I am sure, little but this. But where you and I are concerned, sex by itself doesn't interest us unless it is united with brains and personality; in fact we rather think of the latter first, and the person's sex afterwards... I think very probably that older women will appeal to you much more than younger ones, as they do me. This means that you will probably have to wait a good many years before you find anyone you could wish to marry, but I don't think this need worry you, for there is plenty of time, and very often people who wait get something well worth waiting for.

(16) Vera Brittain letter to Edward Brittain (3rd April, 1917)

Three of our Sisters have been ordered to transfer to Salonika. I wish they would send some of us.... I would volunteer like a shot. Not because the city of malaria and mosquitoes and air-raids and odours suggests many attractions, but because this wandering, unsettled, indefinite sort of life makes one yearn to taste as much as one can of what the war has placed within human experience.

(17) Edward Brittain, letter to Vera Brittain (30th April, 1917)

I only heard this morning from Miss Thurlow that Geoffrey was killed in action on April 23rd - a week ago today - and I sent you a cable about noon... Always a splendid friend with a splendid heart and a man who won't be forgotten by you or me however long or short a time we may live. Dear child, there is no more to say; we have lost almost all there was to lose and what have we gained? Truly as you say has patriotism worn very very threadbare.

(18) Vera Brittain letter to Edward Brittain (4th May, 1917)

As soon as the cable came saying that Geoffrey was killed, only a few hours after the one saying that Victor was hopelessly blind, I knew I must come home. It will be easier to explain when I see you, also - perhaps - to consult you about something I can't possibly discuss in a letter. Anyone could take my place here, but I know that nobody else could take the place that I could fill just now at home....

I can't tell you how I shall miss Geoffrey - I think he meant more to me that anyone after Roland and you. as for you I dare not think how lonely you must feel with him dead and Victor perhaps worse, for it makes me too impatient of the time that must elapse before I can see you - I may not even be able to start for two or three weeks. Geoffrey and I had become very friendly indeed in letters of late, and used to write at least once a week... After Roland he was the straightest, soundest, most upright and idealistic person I have ever known.

(19) Vera Brittain letter to Edith Brittain (4th August, 1917)

I arrived here yesterday afternoon; the hospital is about a mile out of the town, on the side of the hill, in a large clearing surrounded on three sides by woods... The hospital is frantically busy and we were very much welcomed.... You will be surprised to hear that at present I am nursing German prisoners. My ward is entirely reserved for the most acute German surgical cases... The majority are more or less dying; never, even at the 1st London during the Somme push, have I seen such dreadful wounds. Consequently they are all too ill to be aggressive, and one forgets that they are the enemy and can only remember that they are suffering human beings.

(20) Vera Brittain letter to Edith Brittain (5th December, 1917)

We have heaps of gassed cases at present who came in a day or two ago; there are ten in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of ten cases - of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things burnt and blistered all over with great mustard coloured suppurating blisters, with blinded eyes - sometimes temporally, sometimes permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke. The only thing one can say it that such severe cases don't last long; either they die soon or else improve - usually the former; they certainly don't reach England in the state we have them here, and yet people persist in saying that God made War, when there are such inventions of the Devil about.

(21) Vera Brittain described working at the 24th General Hospital in Étaples in her book Testament of Youth (1933)

I am a Sister VAD, and orderly all in one. Quite apart from the nursing, I have stoked the fire all night, done two or three rounds of bed pans, and kept the kettles going and prepared feeds on exceedingly black Beatrice oil stoves and refilled them from the steam kettles utterly wallowing in paraffin all the time. I feel as if I had been dragged through the gutter. Possibly acute surgical is the heaviest type of work there is, I think, more wearing than anything else on earth. You are kept on the go the whole time but in the end there seems to be nothing definite to show for it - except that one or two are still alive that might otherwise have been dead.

The picture came back to me of myself standing alone in a newly created circle of hell during the 'emergency' of March 22nd 1918, gazing half hypnotized at the disheveled beds, the stretchers on the floor, the scattered boots and piles of muddy clothing, the brown blankets turned back from smashed limbs bound to splints by filthy bloodstained bandages. Beneath each stinking wad of sodden wool and gauze an obscene horror waited for me and all the equipment that I had for attacking it in this ex-medical ward was one pair of forceps standing in a potted meat glass half full of methylated spirit.

The cold is terrific; the windows of the ward are all covered with icicles. I'm going about in a jersey and long coat. By the middle of December out kettles, hot water bottles and sponges were all frozen hard when we came off duty if we had not carefully emptied and squeezed them the night before. Getting up to go on duty in the icy darkness was a shuddering misery almost as exacting as an illness.

Our vests, if we hung them over a chair, went stiff and we could keep them soft only if we slept in them. All the taps froze; water for the patients had to be cut down to a minimum and any spilt in the passages turned in a few seconds to ice.

Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line. We have heaps of gassed cases at present: there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes - sometimes temporally, some times permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke.

The strain is very, very great. The enemy is within shelling distance - refugee sisters crowding in with nerves all awry - bright moonlight, and aeroplanes carrying machine guns - ambulance trains jolting into the siding, all day, all night - gassed men on stretchers clawing the air - dying men reeking with mud and foul green stained bandages, shrieking and writhing in a grotesque travesty of manhood - dead men with fixed empty eyes and shiny yellow faces.

(22) Vera Brittain, Testament of Experience (1957)

Ever since Armistice Day 1918 had found me alone, with my young and dear contemporaries gone, I had been trying to understand why they died. Was not the unthinking acceptance of an aggressive or short-sighted national policy, followed by mass-participation in sociable war-time activities, one of the ingredients which created a militant psychology and made shooting wars possible? I had studied their consequences too, and knew how rapid a deterioration of civilised values followed the initial nobility and generosity, until the Christian virtues themselves came to be regarded with derision.

Surely the path which I had trodden for two decades now summoned me to struggle against that catastrophic process? Though I still underrated the cost of such a stand, I knew that the routine performance of dangerous duties would be stimulating and congenial compared with the exhausting demands of independent thought and the task of maintaining, against the deceptive surge of popular currents, a conscious realisation of what was actually happening.

And where, apart from the usual writings and speeches, could I newly begin? An idea suddenly came from my endeavours to answer the daily quota of letters from unknown correspondents which had increased so rapidly since the outbreak of war. Some wanted to help others to be helped; all were eager to stop hostilities. One correspondent hopefully suggested that the women of the world should immediately unite, and call a truce.

By means of a regular published letter I could not only reply to these anxious, bewildered people, but seek out and rally such independent-minded commentators as the author who wrote to deplore the lack of vision among Britain's rulers.

A periodic word to similar correspondents, if based on determined research behind the news, could elucidate vital issues for the doubting, galvanise the discouraged, and assure the isolated that ' they were not alone. Its title, I thought, might be Letter to Peace Lovers, for the group that I hoped to reach was much wider than the small bodies of organised war-resisters.

(23) Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth (1933)

I was staring gloomily at the Oxford engravings and photographs graphs of the Dolomites which clustered together so companionably upon the Dean's study wall, when Winifred Holtby burst suddenly in upon this morose atmosphere of ruminant lethargy. Superbly tall, and vigorous as the young Diana with her long straight limbs and her golden hair, her vitality smote with the effect of a blow upon my jaded nerves. Only too well aware that I had lost that youth and energy for ever, I found myself furiously resenting its possessor. Obstinately disregarding the strong-featured, sensitive face and the eager, shining blue eyes, I felt quite triumphant because-having returned from France less than a month before - she didn't appear to have read any of the books which the Dean had suggested as indispensable introductions to our Period.

(24) Circular sent out to people considering subscribing to Letters to Peace Lovers (1939)

What I do want is to consider and discuss with you the ideas, principles and problems which have concerned genuine peace-lovers for the past twenty years. In helping to sustain the spirits of my readers (and through writing to them to invigorate my own). I hope to play a small part in keeping the peace movement together during the dark hours before us. By constantly calling on reason to mitigate passion, and truth to put falsehood to shame, I shall try, so far as one person can, to stem the tide of hatred which in wartime rises so quickly that many of us are engulfed before we realise it.

In a word, I want to help in the important task of keeping alive decent values at a time when these are undergoing the maximum strain.

My only object is to keep in close personal touch with all who are deeply concerned that war shall end and peace return and who understand what Johan Bojer meant when he wrote: "I went and sowed corn in mine enemy's field that God might exist".

(25) Vera Brittain, Letters to Peace Lovers (25th October, 1939)

Even supposing that we do destroy Hitler, we shall not again be confronted by a Europe agreeably free from competitors for power. The disappearance of Herr Hitler will probably lead instead to a revolutionary situation in Germany, controlled by puppets who own allegiance to another Power. We, the democracies, will still be faced by totalitarianism, in a form less clumsy but no less aggressive, and even more sinister in its ruthless unexhausted might.

(26) Frances Partridge, diary entry (25th January, 1940)

Spent most of the morning reading Vera Brittain on Winifred Holtby - frightfully bad, but it aroused various reflections. It is a glorification of the second-rate and sentimental and reeks of femininity. Why should woman on woman so painfully lack irony, humour or bite? And it's too winsome and noble, somehow. But much of that belongs to the First War, and not to women only. (There it is in Rupert Brooke.) A musty aroma of danger glamourized and not understood by girls at home floats out of this book. Vera Brittain writes of the number of women now happily married and with children who still hark back to a khaki ghost which stands for the most acute and upsetting feelings they have ever had in their lives. Which is true I think, and the worst of it is that the ghost is often almost entirely a creature of their imagination.

(27) Shirley Williams, Climbing the Bookshelves (2009)

My parents, my brother and I, and my mother's dear friend Winifred Holtby lived in a long, thin house at 19 Glebe Place, Chelsea, a street much favoured by artists, actors and other Chelsea characters. John and I loved Auntie Winifred. Tall and blonde, she radiated a gaiety that helped to dispel the sadness in my mother's life. They had met at Somerville college, Oxford, and had sharedd flats in London. Both were regarded as progressive writers, addressing topics like feminism and equal rights not much discussed in conventional society.

Some critics and commentators have suggested that their relationship must have been a lesbian one. My mother deeply resented this. She felt that it was inspired by a subtle anti-feminism to the effect that women could never be real friends unless there was a sexual motivation, while the friendships of men had been celebrated in literature from classical times. My mother was instinctively heterosexual. But as a famous woman author holding progressive opinions, she became an icon to feminists and in particular to lesbian feminists. She sometimes took me with her when she met lesbian women who were besotted with her, to indicate her own commitment to marriage and family.

(28) Shirley Williams, Climbing the Bookshelves (2009)

Determinedly professional, my mother was at work in her study by 10am, after reading the newspapers and the morning's letters, sorting out the shopping lists and paying the bills. Her study was a sacred place, of blotters and pens in black-and-gold stands, of carefully ranged notepaper and envelopes, and of manuscripts composed in her neat, rounded script. Only death, war or a serious accident would justify interrupting her there.

My parents spent the mornings in their separate studies, but meals were sociable occasions. Politics invaded our conversations. Mussolini stalked through our soup and Franco smirked in our puddings.

Hitler's relentless ascent to power became an ever-darkening shadow over our ordered lives. I, of course, understood little of all this. What I did understand was that no one would pay me any attention unless I engaged in political conversation too. "You're only interested in Hitler, not me." I informed them at the age of five.